Chandrakirti

Chandrakirti was a seventh-century Indian Buddhist philosopher, revered for his interpretation of Nagarjuna's teachings on the Middle Way.

Chandrakirti

-

The Moon of Wisdom$39.95- Paperback

The Moon of Wisdom$39.95- PaperbackBy Chandrakirti

By The Eighth Karmapa Mikyo Dorje

Translated by Ari Goldfield

Translated by Jules B. Levinson

Translated by Jim Scott

Translated by Birgit Scott

Translated by Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso -

Introduction to the Middle Way$32.95- Paperback

Introduction to the Middle Way$32.95- PaperbackBy Jamgon Mipham

By Chandrakirti

Translated by Padmakara Translation Group

GUIDES

Nagarjuna

Nagarjuna

circa 150 – c. 250 CE

Of Nagarjuna’s life, we know almost nothing. He is said to have been born into a Brahmin family in the south of India around the beginning of the second century CE. He became a monk and a teacher of high renown and exerted a profound and pervasive influence on the evolution of the Buddhist tradition in India and beyond. Much of his life seems to have been spent at Sriparvata in the southern province of Andhra Pradesh, at a monastery built for him by king Gotamiputra, for whom he composed the Suhrllekha, his celebrated Letter to a Friend.

Nagarjuna is intimately associated with the Prajnaparamita sutras, the teachings on the Perfection of Wisdom, the earliest-known examples of which seem to have appeared in written form around the first century BCE, thus coinciding with the emergence of Mahayana, the Buddhism of the Great Vehicle.

It is recorded in the Pali Canon that the Buddha foretold the disappearance of some of his most profound teachings. They would be misunderstood and neglected, and would fall into oblivion. “In this way,” he said, “those discourses spoken by the Tathāgata that are deep, deep in meaning, supramundane, dealing with emptiness, will disappear.” There is no knowing whether on that occasion he was referring to the Perfection of Wisdom, but it is certain that the earliest exponents of the Mahayana believed that, with the Prajnaparamita scriptures, they were recovering a profound and long-lost doctrine. Nagarjuna seems to have been deeply implicated in this rediscovery. Questions of historicity aside, the story that he brought back seven volumes of the Prajnaparamita sutras from the subterranean realm of the nagas, where they had been preserved, conveys a clear message. In the eyes of Nagarjuna’s contemporaries and of later generations, the appearance of the Prajnaparamita sutras marked a new beginning in the history of Buddhism, and yet the teachings they contained were not innovations. And in their interpretation and propagation, Nagarjuna played a crucial role.

-Excerpted from the "Translator's Preface," The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way translated by Padmakara Translation Group

Jump to sections on this page:

Nagarjuna's Life | Madhayamaka & Reasoning | Praises

Advice | Tantra | Recent Works on Madhyamaka | Other Works and Resources

Nagarjuna's Life

A more comprehensive biography of Nagarjuna can be found in Butön's History of Buddhism in India and Its Spread to Tibet. A fourteenth-century Tibetan classic that serves as an excellent introduction to basic Buddhism as practiced throughout India and Tibet and describes the process of entering the Buddhist path through study and reflection.

What follows is a brief composite biography from a variety of sources including Butön Rinchen Drup's biography of Nagarjuna.

Overcoming his fated death

Nagarjuna was born to a Brahmin family in Vidarbha in present-day Maharashtra, India. Predicted to have a short life, he avoided an early demise by taking ordination at Nalanda monastery with Rahulabhadra, identified in some accounts as being the mahasiddha Saraha and in others as being the abbot of Nalanda; regardless, he is best known for his works in praise of Prajñaparamita. With an ordination name of Sriman, Nagarjuna undertook thorough studies of Buddhist teachings and became successful in defeating both Buddhists and non-Buddhists in debate.

Prajñaparamita sutras

Several nagas heard Sriman's teaching and subsequently invited him down into their realm, from which he later brought back special naga clay that was used in the construction of many temples and stupas. He also brought back, most famously, important Prajñaparamita sutras. Thenceforth he became known as Nagarjuna.

Butön describes the meaning of the name beautifully:

Naga signifies birth from the basic space of phenomena, abiding in neither the extreme of eternalism or nihilism, mastery over the vault of precious scriptures, and being endowed with the view that burns and illuminates. Arjuna signifies one who has procured worldly power. Thus, he is named Arjuna because he governs the kingdom of the doctrine and subdues the hosts of faulty enemies. Taken together, these two parts form the name "Nagarjuna."

Nagarjuna's activities were vast; his better-known accomplishments include the building of two structures in Bodhgaya- the stone fence around the Vajra Seat beneath the Bodhi tree and the stupa that sits atop the Mahabodhi Temple - as well as the wall around the great Dhanyakataka Stupa at Amaravati in present-day Andhra Pradesh.

Karma at work

Nagarjuna passed away when he offered his head to a greedy prince who thought he could ensure his own long life by killing Nagarjuna. No blade would cut Nagarjuna, but he told the prince that in a past life he had killed an insect with a blade of kusha grass, so his head could be cut off with a blade of that grass which the prince then did.

It is believed that Nagarjuna's head and body were separated but do not decay and over time move closer together. Once they rejoin, his activity will continue.

Nagarjuna's Texts

The Tibetan Tengyur ascribes about one hundred eighty texts on both the sutras and tantras to him. There is a lot of scholarly debate about what Nagarjuna did and did not actually write, which is outside the scope of this article. Instead, we will focus on the major works widely attributed to him that are available in English.

His treatises are divided in various ways. Mabja Jangchub Tsondru divides them into three groups:

- Those belonging to the Causal Vehicle of Characteristics

- Those belonging to the Resultant Vehicle of Secret Mantra

- Those that show the two above to be identical in meaning

A bit arbitrarily, we will follow another traditional division which groups the treatises as follows: works on reasoning, praises, and advice. This schema ignores the large body of work on tantra and medicine, but most of what is available in English is included in these three groupings.

Nagarjuna on Madhyamaka & Reasoning

To him who taught that things arise dependently,

Not ceasing, not arising,

Not annihilated nor yet permanent,

Not coming, not departing,

Not different, not the same:

The stilling of all thought, and perfect peace:

To him, the best of teachers, perfect Buddha, I bow down.

The above verse is from Nagarjuna's famed Root Stanzas of the Middle Way—by far his most widely studied text.

The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way

This volume presents a new English translation of the founding text of the Madhyamaka (Middle Way) school of Mahayana Buddhism, Nagarjuna’s Root Stanzas of the Middle Way (Mulamadhyamakakarika) and includes the Tibetan version of the text. The Root Stanzas holds an honored place in all branches of Tibetan Buddhism, as well as in the Buddhist traditions found in China, Japan, and Korea, because of the way it develops the seminal view of emptiness (shunyata), which is crucial to understanding Mahayana Buddhism and central to its practice. It is prized for its pithy and pointed arguments that show that things lack intrinsic being and thus are “empty” (shunya). They abide in the Middle Way, free from the extremes of permanence and annihilation.

This translation was done following the commentary by Mipham Rinpoche, thus appealing to a living tradition that stretches back unbroken to the Tibetan translators and through their Sanskrit mentors to Nagarjuna himself.

The present work contains Nagarjuna's verses on the Middle Way accompanied by Mabja Jangchub Tsöndrü's famed commentary, the Ornament of Reason. Active in the twelfth century, Mabja was among the first Tibetans to rely on the works of the Indian master Candrakirti, and his account of the Middle Way exercised a deep and lasting influence on the development of Madhyamaka philosophy in all four schools of Buddhism in Tibet. Sharp, concise, and yet comprehensive, the Ornament of Reason has been cherished by generations of scholar-practitioners. The late Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen Rinpoche, a renowned authority on the subject, often referred to this commentary as "the best there is." A visual outline of the commentary has been added that clearly shows the structure of each chapter and makes the arguments easier to follow.

Hardcover | eBook

$27.99 - eBook

Paperback | eBook

$24.95 - Paperback

The Sun of Wisdom: Teachings on the Noble Nagarjuna's Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way

by Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso

An excellent contemporary commentary on the Mulamadhyamakakarika is Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso's The Sun of Wisdom. Focusing on the most important root verses, it is a very accessible entryway into this fundamental but challenging text.

As Khen Rinpoche says,

All the verses in this book are excellent supports for developing your precise knowledge of genuine reality through study, reflection, and meditation. You should recite them as much as possible, memorize them, and reflect on them until doubt-free certainty in their meaning arises within. Then you should recall their meaning again and again, to keep your understanding fresh and stable. Whenever you have time, use them as the support for the practices of analytical and resting meditation. If you do all of this, it is certain that the sun of wisdom will dawn within you, to the immeasurable benefit of yourselves and others.

Paperback | eBook

$27.95 - Paperback

by David Ross Komito and Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Nagarjuna's Shunyatasaptati, or Seventy Stanzas on Emptiness (there are actually seventy-three), is an expansion of the seventh section of the Root Verses, "Analysis of Characteristics of the Conditioned," that addresses some questions people had about the presentation of conditioned phenomena and whether that conflicted with sutra teachings. As is often the case, the answer lies in the difference between the conventional point of view of beings and how things actually are.

Additional Texts on Reasoning by Other Publishers

Of the remaining texts in this category,

- Nagarjuna's Yuktisastika, or Sixty Verses on Reasoning, has been translated by Joseph Loizzo as Nagarjuna's Reason Sixty and is available from Columbia University Press.

- The Vigrahavyavartani, or Refutation of Objections, was translated most recently by Jan Westerhoff and published as The Dispeller of Disputes by Oxford University Press.

- And lastly, Nagarjuna's Vaidalyaprakarana is included in Nagarjuniana by Christian Lindtner, published by Motilal Banarsidass.

Nagarjuna's Praises

The Tibetan Tengyur identifies eighteen works of praise by Nagarjuna, and this praise is generally directed at Buddha Shakyamuni.

Paperback | eBook

$29.95 - Paperback

Translated and introduced by Karl Brunnholzl

While most of Nagarjuna's praises are directed to Buddha Shakyamuni, the main work of Nagarjuna's praises we have in English is the Dharmadhatustava, translated as In Praise of Dharmadhatu, and this work directs praise instead at the ultimate nature of mind. Karl Brunnhölzl's translation, which includes an in-depth introduction to Nagarjuna and his works in general and this one specifically, also contains a commentary by the Third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje.

The text shows how our buddha nature is obscured by stains but also how the stains can be removed by following the path of the Mahayana and can be fully revealed as buddhahood. Rangjung Dorje's commentary is also of particular interest because even though he is known for his shentong views, this commentary shows how his actual understanding is far more subtle than scholars have sometimes supposed and is in fact an elegant synthesis of the two great streams of the Mahayana, Madhyamaka, and Yogacara.

Paperback | eBook

$49.95 - Paperback

Translated and introduced by Karl Brunnholzl

Three other praises of Nagarjuna's are included in the collection Straight from the Heart, also translated and introduced by Karl Brunnhölzl</a>. Interestingly, in these praises, Nagarjuna often refers to buddhahood in positive terms, in contrast to much of his other work, which deconstructs any possibility of phenomena truly existing. As Brunnhölzl points out, despite there being nothing to pinpoint in the dharmadhatu as the nature of the mind, it can still be experienced directly and personally in a non-referential way. In other words, enlightenment is not some empty, dark nothingness, but wide-awake awareness of mind completely free from reference points.

Nagarjuna's Advice

There are seven texts included in the advice category. The two most famous are the Suhrllekha, or Letter to a Friend, and the Ratnavali, or Nagarjuna's Precious Garland: Buddhist Advice for Living and Liberation.

Paperback | eBook

$24.95 - Paperback

Nagarjuna's Letter to a Friend: With Commentary by Kangyur Rinpoche

Translated by the Padmakara Translation Group

Letter to a Friend is a set of verses of advice to a king whose identity is uncertain but who was most likely one of a number of kings in present-day Andhra Pradesh. There are several translations of Letter to a Friend, the most recent one being by the Padmakara Translation Group, which includes a commentary by Kyabje Kangyur Rinpoche.

The 123 verses are some of the most frequently quoted lines in all of Tibetan Buddhism and are taught often to this day. The text covers the entire Mahayana path, fusing daily conduct with the framework of stages that lead beings to fully enlightened buddhahood. It makes the entire path totally accessible to laypeople, demonstrating how to completely immerse oneself in the spiritual life while still living in society.

Paperback | eBook

$27.95 - Paperback

Translated by Jeffrey Hopkins

Precious Garland has been categorized by some as belonging among Nagarjuna's works on reasoning, but more traditionally it is part of the advice collection.

In the Precious Garland, he offers intimate counsel on how to conduct one's life and how to construct social policies that reflect Buddhist ideals. The advice for personal happiness is concerned first with improving one's condition over the course of lifetimes, and then with release from all kinds of suffering, culminating in Buddhahood. Nagarjuna describes the cause and effect sequences for the development of happiness within ordinary life, as well as the practices of wisdom, realizing emptiness, and compassion that lead to enlightenment. He describes a Buddha's qualities and offers encouraging advice on the effectiveness of practices that reveal the vast attributes of Buddhahood. In his advice on social and governmental policy, Nagarjuna emphasizes education and compassionate care for all living beings. He also objects to the death penalty. Calling for the appointment of government figures who are not seeking profit or fame, he advises that a selfish motivation will lead to misfortune. The book includes a detailed analysis of attachment to sensual objects as a preparation for realization of the profound truth that, when realized, makes attachment impossible.

Nagarjuna on Tantra

The one work we have is not actually by Nagarjuna but the basis for it is Nagarjuna's Piṇḍīkramaḥ and the Sūtramelāpakam.

Guhyasamaja Practice in the Arya Nagarjuna System, Volume One: The Generation Stage

by Gyumé Khensur Lobsang Jampa, translated by Artemus Engle

The Guhyasamāja Tantra is one of the Unexcelled Yoga Tantras of Vajrayana Buddhism. In the initial, generation-stage practice, one engages in a prescribed sequence of visualizations of oneself as an enlightened being in a purified environment in order to prepare one’s mind and body to engage in the second stage: the completion stage. The latter works directly with the subtle energies of one’s mind and body and transforms them into the enlightened mind and body of a buddha. In this book, Gyumé Khensur Lobsang Jampa, a former abbot of Gyumé Tantric College, provides complete instructions on how to practice the generation stage of Guhyasamāja, explaining the visualizations, offerings, and mantras involved, what they symbolize, and the purpose they serve. These instructions, which are usually imparted only orally from master to student after the student has been initiated into the Guhyasamāja mandala, are now being published in English for the first time and are supplemented by extracts from key written commentaries in the footnotes to support practitioners who have received the required transmissions from a holder of this lineage. The complete self-generation ritual is included in the second part of the book, with the Tibetan on facing pages, which can be used by those who read Tibetan and want to recite the ritual in Tibetan.

Hardcover | eBook

$49.95 - Hardcover

Subsequent Commentaries by Great Indian and Tibetan Masters

There are of course so many commentaries and commentaries on commentaries for Nagarjuna's work, by masters including the following:

...and many more great teachers up to the present. Several of these are included in subsequent Great Masters Series articles.

Recent works on Madhyamaka

Other Works and Resources

Paperback | eBook

$19.95 - Paperback

The Prince and the Zombie: Tibetan Tales of Karma

By Tenzin Wangmo, foreword by Matthieu Ricard

One last book should be mentioned here, as it's a bit of a leap from the traditional texts by and literature about Nagarjuna. The Prince and the Zombie: Tibetan Tales of Karma by Tenzin Wangmo is a book based on Tibetan oral folktale traditions.

In this book,was published in the spring of 2015, a young prince encounters Nagarjuna, who guides him and gives him the task of bringing a zombie-that's really the best translation available-back from one of the great charnel grounds of India. It is a story full of magic and excitement and could serve as a brief vacation for the mind in between studying verses on emptiness!

Discover Related Reader's Guides on the Great Masters

Tsongkhapa: A Guide to His Life and Works

The Life of Tsongkhapa Lobsang Drakpa (1357-1419)

Tsongkhapa Lobzang Drakpa (1357–1419), was one of the most important figures in Tibet, historically and philosophically. As the founder of the Gelug school he made an enormous contribution to revitalizing Buddhism in Tibet. Regarded as an emanation of Manjushri--the bodhisattva of wisdom and discerning intelligence, Tsongkhapa was of keen intellect as well as experiential understanding of the Buddhist tradition. He undertook many long retreats during which he had profound visions out of which he wrote many of his celebrated treatises including Lam Rim Chenmo or The Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path. A prolific writer, he composed 210 treatises, compiled into 20 volumes wherein he emphasized the combined paths of Sutra and Tanta. In addition, he established the acclaimed Ganden monastery.

For a longer biography of Tsongkhapa read an excerpt from Geshe Sonam Rinchen's commentary on The Three Principal Aspects of the Path.

"Born in 1357 in Amdo, northeastern Tibet, and educated in central Tibet, Tsongkhapa led a life that exemplified the importance of study, critical reflection, and meditative practice. In an autobiographical poem he declared:

"First I sought wide and extensive learning,

Second I perceived all teachings as personal instructions,

Finally, I engaged in meditative practice day and night;

All these I dedicated to the flourishing of the Buddha’s teaching.By the end of his life, 600 years ago, Tsongkhapa was widely revered across Tibet. He had studied and corresponded with the most renowned teachers of his time, from all the major traditions, and had spent years in meditative retreat."

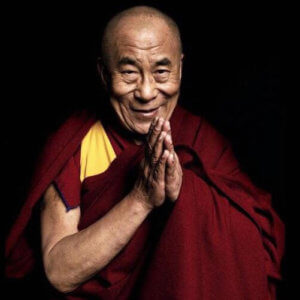

—From the Foreward by H. H. The Dalai Lama, Tsongkhapa: A Buddha in the Land of Snows, by Thupten Jinpa

The Definitive Biography of Tsongkhapa

Paperback | Ebook

$29.95 - Paperback

Marking the 600th anniversary of Tsongkhapa, in 2019 we published what is the most comprehensive, definitive biography of this great figure, written by Thupten Jinpa. The author is best known as the main translator for the Dalai Lama, but he is an author and scholar himself, having earned a Geshe degree. In the author’s words,

this new biography of Tsongkhapa…is aimed primarily at the contemporary reader. And it seeks to answer the following key questions for them: ‘Who was or is Tsongkhapa? What is he to Tibetan Buddhism? How did he come to assume the deified status he continues to enjoy for the dominant Geluk School of Tibetan Buddhism? What relevance, if any, do Tsongkhapa’s thought and legacy have for our contemporary thought and culture?

—Thupten Jinpa, from the Introduction to Tsongkhapa: A Buddha in the Land of Snows

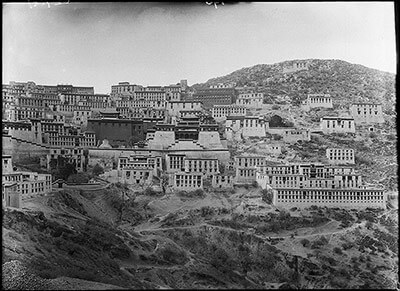

Ganden monastery, founded by Tsongkhapa, photographed in 1921 by Sir Charles Bell

Whoever sees or hears

Or contemplates these prayers,

May they never be discouraged

In seeking the bodhisattva’s amazing aspirations.

By praying with such expansive thought

Created from the power of pure intention,

May I achieve the perfection of prayers

And fulfill the wishes of all sentient beings.

Tsongkhapa's Lam Rim Chenmo, The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment

Tsongkhapa's main contribution to this genre is the famous Lamrim Chenmo or The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. It is also generally considered his most influential work, studied and practiced by tens of thousands today.

The background to this work is on one of Tsongkhapa’s own letters to a lama, included in Art Engle's The Inner Science of Buddhist Practice, where he describes it as building on Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment:

“It is clear that this instruction [introduced] by [Atisha] Dīpaṃkara Śrījnāna on the stages of the path to enlightenment . . . teaches [the meanings contained in] all the canonical scriptures, their commentaries, and related instruction by combining them into a single graded path. One can see that when taught by a capable teacher and put into practice by able listeners it brings order, not just to some minor instruction, but to the entire [body of] canonical scriptures. Therefore, I have not taught a wide variety of [other] instructions.”

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Vol. 1-3)

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Tib. Lam rim chen mo) is one of the brightest jewels in the world’s treasury of sacred literature. The author, Tsong-kha-pa, completed it in 1402, and it soon became one of the most renowned works of spiritual practice and philosophy in the world of Tibetan Buddhism. Because it condenses all the exoteric sūtra scriptures into a meditation manual that is easy to understand, scholars and practitioners rely on its authoritative presentation as a gateway that leads to a full understanding of the Buddha’s teachings.

Tsong-kha-pa took great pains to base his insights on classical Indian Buddhist literature, illustrating his points with classical citations as well as with sayings of the masters of the earlier Kadampa tradition. In this way the text demonstrates clearly how Tibetan Buddhism carefully preserved and developed the Indian Buddhist traditions.

Paperback| Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

(Volume 1)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This first of three volumes covers all the practices that are prerequisite for developing the spirit of enlightenment (bodhicitta).

Paperback| Ebook

$28.95 - Paperback

(Volume 2)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This second of three volumes covers the deeds of the bodhisattvas, as well as how to train in the six perfections.

Paperback| Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

(Volume 3)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This third and final volume contains a presentation of the two most important topics in the work: meditative serenity (śamatha) and supramundane insight into the nature of reality (vipaśyanā).

Commentaries on Tsongkhapa's Great Treatise and other Lam Rim (Stages of the Path) texts

"The Great Treatise was written by Lama Tsong-kha-pa, a great scholar, a real holder of the Nalanda tradition. I think he is one of the very best Tibetan scholars. Although it is now widely available in Tibetan as well as English, you see that I brought with me today my own personal copy of this text. On March 17th, 1959, when I left Norbulingka that night, I brought this book with me. Since then I have used it ten or fifteen times to give teachings, all from this copy. So this is something very dear to me."

-H.H The Dalai Lama discussing his copy of the Great Treatise in From Here to Enlightenment

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

From Here to Enlightenment

An Introduction to Tsong-kha-pa's Classic Text The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment

By H.H. The Dalai Lama and translated by Guy Newland

When the Dalai Lama was forced into exile in 1959, he could take only a few items with him. Among these cherished belongings was his copy of Tsong-kha-pa’s classic text The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. This text distills all the essential points of Tibetan Buddhism, clearly unfolding the entire Buddhist path.

In 2008, celebrating the long-awaited completion of the English translation of the Great Treatise, the Dalai Lama gave a historic six-day teaching at Lehigh University to explain the meaning of the text and underscore its importance. It is the longest teaching he has ever given to Westerners on just one text—and the most comprehensive. From Here to Enlightenment makes the teachings from this momentous event available for a wider audience.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

Introduction to Emptiness

As Taught in Tsong-kha-pa's Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path

By Guy Newland

Readers are hard-pressed to find books that can help them understand the central concept in Mahayana Buddhism—the idea that ultimate reality is emptiness. In clear language, Introduction to Emptiness explains that emptiness is not a mystical sort of nothingness, but a specific truth that can and must be understood through calm and careful reflection. Newland's contemporary examples and vivid anecdotes will help readers understand this core concept as presented in one of the great classic texts of the Tibetan tradition, Tsong-kha-pa's Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. This new edition includes quintessential points for each chapter.

Paperback | Ebook

$17.95 - Paperback

Refining Gold

Stages in Buddhist Contemplative Practice

By H.H. The Dalai Lama

In this extensive teaching, the Dalai Lama beautifully elucidates the meaning of the path to enlightenment through his own direct spiritual advice and personal reflections. Based on two very famous Tibetan text—Tsongkhapa's Song of the Stages on the Spiritual Path and the Third Dalai Lama's Essence of Refined Gold—this teaching presents in practical terms the essential instructions for the attainment of enlightenment. Its direct approach and lucid style make Refining Gold one of the most accessible introductions to Tibetan Buddhism ever published. His discourse draws out the meaning of the Third Dalai Lama’s famous Essence of Refined Gold as he speaks directly to the reader, offering advice, personal reflections, and scriptural commentary. He says in practical terms what the student must do to attain enlightenment.

Tsongkhapa's Three Principle Aspects of the Path

This is the shortest Lamrim text Tsongkhapa composed. Tsongkhapa wrote the fourteen stanzas of this classic distillation of all the paths of practice that lead to enlightenment. The three principal elements of the path referred to are: (1) renunciation, tied to the wish for freedom from cyclic existence; (2) the motivation to attain enlightenment for the benefit of others; (3) cultivating the correct view that realizes emptiness.

Paperback | eBook

$21.95 - Paperback

Three Principal Aspects of the Path

By Geshe Sonam Rinchen, edited and translated by Ruth Sonam

The wish for freedom, the altruistic intention, and the wisdom realizing emptiness constitute the essence of the Buddhist path. In this teaching, Geshe Sonam Rinchen explains, in clear and readily accessible terms, Je Tsongkhapa’s (1357–1419) famed presentation of these three essential topics.

The Three Principal Aspects is also included in Cutting Through Appearances: Practice and Theory of Tibetan Buddhism in which Geshe Sopa annotates the Fourth Panchen Lama’s instructions on how to practice this text in a meditation session.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama teaches on this text, and this is included as the chapter “The Path to Enlightenment” in Kindness, Clarity, and Insight.

Paperback | Ebook

$39.95 - Paperback

Paperback | Ebook

$16.95 - Paperback

Paperback | eBook

$29.95 - Paperback

Another work where Tsongkhapa’s Lamrim is featured is in Changing Minds: Contributions to the Study of Buddhism and Tibet in Honor of Jeffrey Hopkins. There are three chapters devoted to Tsongkhapa:

- Guy Newland’s Ask a Farmer: Ultimate Analysis and Conventional Existence in Tsongkhapa’s Lam Rim Chen Mo

- Daniel Cozort’s Cutting the Roots of Virtue: Tsongkhapa on the Results of Anger

- Elizabeth Napper’s Ethics as the Basis of a Tantric Tradition: Tsongkhapa and the Founding of the Gelugpa Order

Lotsawa House also includes a translation of these fourteen stanzas.

Tsongkhapa on Madhyamaka, The Middle Way School

Tsongkhapa is known for his distinct approach to the middle way philosophical system (madhyamaka) propounded by Indian masters Nāgārjuna (circa 200 CE) and Candrakīrti (circa 600 CE).

"I first went to India in 1972 on a dissertation research Fulbright fellow-ship, where although advised by the Fulbright Commission in New Delhi not to go to Dharmsala because of possible political complications, I went after a brief trip to Banaras. There I found that the Dalai Lama was about to begin a sixteen-day series of four- to six-hour lectures on Tsong-kha-pa Lo-sang-drak-pa’s Medium-Length Exposition of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment Practiced by Persons of Three Capacities. Despite my cynicism that a governmentally appointed reincarnation could possibly have much to offer, I slowly became fascinated first with the strength and speed of his articulation and then, much more so, with the touching meanings that were conveyed."

-Jeffrey Hopkins, from the Preface to Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom

Paperback | eBook

$44.95 - Paperback

Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom

By Jeffrey Hopkins

In fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Tibet there was great ferment about what makes enlightenment possible, since systems of self-liberation must show what factors pre-exist in the mind that allow for transformation into a state of freedom from suffering. This controversy about the nature of mind, which persists to the present day, raises many questions. This book first presents the final exposition of special insight by Tsong-kha-pa, the founder of the Ge-luk-pa order of Tibetan Buddhism, in his medium-length Exposition of the Stages of the Path as well as the sections on the object of negation and on the two truths in his Illumination of the Thought: Extensive Explanation of Chandrakirti's Supplement to Nagarjuna's "Treatise on the Middle." It then details the views of his predecessor Dol-po-pa Shay-rap Gyel-tsen, the seminal author of philosophical treatises of the Jo-nang-pa order, as found in his Mountain Doctrine, followed by an analysis of Tsong-kha-pa's reactions. By contrasting the two systems—Dol-po-pa's doctrine of other-emptiness and Tsong-kha-pa's doctrine of self-emptiness—both views emerge more clearly, contributing to a fuller picture of reality as viewed in Tibetan Buddhism. Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom brilliantly explicates ignorance and wisdom, explains the relationship between dependent-arising and emptiness, shows how to meditate on emptiness, and explains what it means to view phenomena as like illusions.

Paperback

$34.95 - Paperback

The Ornament of the Middle Way

A Study of the Madhyamaka Thought of Santaraksita

By James Blumenthal

The late James Blumenthal explores this important text by Shantarakshita and brings in Tsongkhapa’s text on this subject.

Shantarakshita's The Ornament of the Middle Way is among the most important Mahayana Buddhist philosophical treatises to emerge on the Indian subcontinent. In many respects, it represents the culmination of more than 1300 years of philosophical dialogue and inquiry since the time of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. Shantarakshita set forth the foundation of a syncretic approach to contemporary ideas by synthesizing the three major trends in Indian Buddhist thought at the time (the Madhyamaka thought of Nagarjuna, the Yogachara thought of Asanga, and the logical and epistemological thought of Dharmakirti) into one consistent and coherent system. Shantarakshitas's text is considered to be the quintessential exposition or root text of the school of Buddhist philosophical thought known in Tibet as Yogachara-Svatantrika-Madhyamaka. In addition to examining his ideas in their Indian context, this study examines the way Shantarakshita's ideas have been understood by and have been an influence on Tibetan Buddhist traditions. Specifically, Blumenthal examines the way scholars from the Geluk School of Tibetan Buddhism have interpreted, represented, and incorporated Santaraksita's ideas into their own philosophical project. This is the first book-length study of the Madyamaka thought of Shantarakshita in any Western language. It includes a new translation of Shantarakshita's treatise, extensive extracts from his autocommentary, and the first complete translation of the primary Geluk commentary on Shantarakshita's treatise.

"As a religious reformer, he has been likened to Luther by Western Buddhologists; but as a religious scholar he is regarded in his own culture as a genius whose statue more closely parallels that of Aquinas in Western Christianity. For Tsongkhapa created his own unique interpretation of Buddhist systematics and hermeneutics, in which he synthesized themes from all the Tibetan Buddhist traditions of his era. For these reasons he was praised by the Eight Karmapa as Tibet's chief exponent of ultimate truth, who revived the Buddha's doctrine at a time when the teachings of all four major Tibetan Buddhist lineages were in decline."

-B. Alan Wallace, from the Preface to Balancing the Mind

Paperback | eBook

$24.95 - Paperback

Balancing the Mind

A Tibetan Buddhist Approach to Refining Attention

By B. Alan Wallace

For centuries, Tibetan Buddhist contemplatives have directly explored consciousness through carefully honed and rigorous techniques of meditation. B. Alan Wallace explains the methods and experiences of Tibetan practitioners and compares these with investigations of consciousness by Western scientists and philosophers. Balancing the Mind includes a translation of the classic discussion of methods for developing exceptionally high degrees of attentional stability and clarity by fifteenth-century Tibetan contemplative Tsongkhapa.

Tsongkhapa and the Debate over the Two Truths

Tsongkhapa is famous—and in some circles controversial—for his presentation and positioning of the Prasangika view of Madhyamaka. Any discussion or debate of this subject invariably references Tsongkhapa.

Hardcover | eBook

$78.00 - Hardcover

The Center of a Sunlight Sky

Madhyamaka in the Kagyu Tradition

By Karl Brunnhölzl

This comprehensive work by Karl Brunnholzl explores all facets of Madhyamaka in the Kagyu tradition, but no analysis of Madhyamaka can leave out Tsongkhapa who appears throughout this work. There is a sixty-page section comparing the views of Tsongkhapa to those of Mikyo Dorje’s “whose writing, not only is a reaction to the position of Tsongkhapa and his followers but addresses most of the views on Madhyamaka that were current in Tibet at the time, including the controversial issue of ‘Shentong-Madhyamaka.’”

Paperback| eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Adornment of the Middle Way

Shantarakshita's Madhyamakalankara with Commentary by Jamgon Mipham

By Jamgon Mipham, translated by Padmakara Translation Group

For a different take on Shantarakshita's The Ornament of the Middle Way (same text, differently translated title) The Adornment of the Middle Way translated by the Padmakara Translation Group, gives a helpful introduction on the various interpretations. This longer passage offers a glimpse into some of the fault lines in the debate:

"The brilliance of Tsongkhapa’s teaching, his qualities as a leader, his emphasis on monastic discipline, and the purity of his example attracted an immense following. Admiration, however, was not unanimous, and his presentation of Madhyamaka in particular provoked a fierce backlash, mainly from the Sakya school, to which Tsongkhapa and his early disciples originally belonged. These critics included Tsongkhapa’s contemporaries Rongtön Shakya Gyaltsen (1367–1449) and Taktsang Lotsawa (1405–?), followed in the next two generations by Gorampa Sonam Senge (1429–1487), Serdog Panchen Shakya Chokden (1428–1509), and the eighth Karmapa, Mikyö Dorje (1505–1557). All of them rejected Tsongkhapa’s interpretation as inadequate, newfangled, and unsupported by tradition. Although they recognized certain differences between the Prasangika and Svatantrika approaches, they considered that Tsongkhapa had greatly exaggerated the divergence of view. They believed that the difference between the two subschools was largely a question of methodology and did not amount to a disagreement on ontological matters.

Not surprisingly, these objections provoked a counterattack, and they were vigorously refuted by Tsongkhapa’s disciples. In due course, however, the most effective means of silencing such criticisms came with the ideological proscriptions imposed at the beginning of the seventeenth century. These followed the military intervention of Gusri Khan, who put an end to the civil war in central Tibet, placed temporal authority in the hands of the Fifth Dalai Lama, and ensured the rise to political power of the Gelugpa school. Subsequently, the writings of all the most strident of Tsongkhapa’s critics ceased to be available and were almost lost. It was, for example, only at the beginning of the twentieth century that Gorampa’s works could be fully reassembled, whereas Shakya Chokden’s works, long thought to be irretrievably lost, were discovered only recently in Bhutan and published as late as 1975."

-from the Introduction to The Adornment of the Middle Way

The Wisdom Chapter

Jamgön Mipham's Commentary on the Ninth Chapter of The Way of the Bodhisattva

By Jamgon Mipham, translated by Padmakara Translation Group

This work on the Wisdom Chapter of Shantideva’s classic, written more than four centuries after Tsongkhapa, is a presentation of a different view than that expounded by Tsongkhapa. It is, in fact, a superb source for understanding the impact of his Madhyamaka presentation in a wider context, historically and philosophically. The extensive introduction gives a very complete and comprehensive account. In sum:

"In his treatment of the Gelugpa account, Mipham concurs in all important respects with Gorampa and the rest of Tsongkhapa’s earlier critics. Indeed, his critique is possibly even more effective in being expressed moderately and without vituperation. Nevertheless, he is careful never to attack Tsongkhapa personally. Given the fact that Mipham was a convinced upholder of the nonsectarian movement, there is no reason to doubt the sincerity of the humble and respectful manner with which he invariably refers to Tsongkhapa. No sarcasm is detectable in his words:

In the snowy land of Tibet, the great and venerable lord Tsongkhapa was unrivaled in his activities for the sake of the Buddha’s teaching. And with regard to his writings, which are clear and excellently composed, I do indeed feel the greatest respect and gratitude.

There is, however, a striking contrast between Mipham’s veneration of Tsongkhapa, on the one hand, and his penetrating critique of his view, on the other. Mipham’s assessment seems to oscillate between an approbation of some of Tsongkhapa’s positions, regarded as unproblematic expressions of a Svātantrika approach that Mipham valued, and a determination to demolish Tsongkhapa’s philosophical innovations and their pretended Prāsaṅgika affiliations. This discrepancy has led some scholars to accuse Mipham of inconsistency. Closer scrutiny suggests, however, that Mipham’s admittedly complex attitude to Tsongkhapa was in point of fact quite coherent."

-from the Introduction to The Wisdom Chapter

Tsongkhapa's Poetry and Songs of Realization

Paperback

$22.95 - Paperback

Thupten Jinpa’s collection of Tibetan poetry includes two poems by Tsongkhapa including Reflections on Emptiness, which is extracted from a larger work, the rTag tu ngu’i rtogs brjod—a poetic retelling of the story of the bodhisattva Sadāprarudita, who is associated with the 8,000 Verse Prajnamaramita Sutra and A Prayer for the Flourishing of Virtues.

Jinpa presents Tsongkhapa’s poetry first in terms of his mastery of composition and second, in terms of his mastery of the Buddhist path.

First, describing his master of composition, Jinpa writes:

Tsongkhapa’s famous long poem entitled ‘‘A Literary Gem of Poetry’’ uses a single vowel in every stanza throughout the entire length. This is the poem from which come the famous lines:

Good and evil are but states of the heart:

When the heart is pure, all things are pure;

When the heart is tainted, all things are tainted.

So all things depend on your heart.In the original Tibetan, this stanza uses only the vowel a. Of course, this kind of literary device can never be reproduced in a translation, whatever the virtuosity and command of the translator.

Second, describing his mastery of the Buddhist path Jinpa states:

To a contemporary reader, Tsongkhapa’s famous ‘‘Prayer for the Flourishing of Virtues’’ gives an insight into the deepest ideals of a dedicated Tibetan Buddhist practitioner; it presents a map of progressive development on the path. Beyond this, the mystic must utterly transform the very root of his identity and the perceptions that arise from it. From the ordinary patterns of action and reaction that make up our psyche and emotional life, the meditator must move toward a divine state of altered consciousness where all realities, including one’s own self, are manifested in their enlightened forms. In other words, the meditator must perfect all dimensions of his or her identity and experience, including rationality, emotion, intuition, and even sexuality. This, in Tibetan Buddhism, is the mystical realm of tantra.

Tsongkhapa and Tantra

A brief note. For those unfamiliar or only exposed through books, we strongly encourage readers to study tantra under the guidance of a qualified teacher. Book reading can only take you so far as the transmission of tantric teaching is about more than what can be put on paper.

This work is analogous to the tantra version of the Lamrim Chenmo, presenting tantra from the position of the sarma, ie., the 'new school,' or later transmission from India.

There are three books by Tsongkhapa and His Holiness the Dalai Lama that form a series focused on Tsongkhapa's Great Exposition of Secret Mantra. In this text, Tsongkhapa presents the differences between sutra and tantra and the main features of various systems of tantra. Each of the three books below begins with the Dalai Lama contextualizing and commenting on the points presented in Tsongkhapa's text, followed by a translation of the corresponding part of the text itself.

Paperback

$29.95 - Paperback

In Volume 1: Tantra in Tibet, the foundations of motivation, refuge, and the Hinayana and Mahayana paths are presented. He then gives an overview of tantra, the notion of Clear Light, the greatness of mantra, and initiation or empowerment.

This revised work describes the differences between the Great Vehicle and Lesser Vehicle streams in the sutra tradition, and between the sutra tradition and that of tantra generally. It includes highly practical and compassionate explanations from H.H. the Dalai Lama on tantra for spiritual development; the first part of the classic Great Exposition of Secret Mantra text; and a supplement by Jeffrey Hopkins on the difference between the Vehicles, emptiness, psychological transformation, and the purpose of the four tantras.

Paperback

$29.95 - Paperback

In Volume II: Deity Yoga, His Holiness discusses deity yoga at length with a particular focus on action and performance tantras (the first two categories of tantra as described in the sarma, or “new translation” schools).

This revised work describes the profound process of meditation in Action (kriya) and Performance (carya) Tantras. Invaluable for anyone who is practicing or is interested in Buddhist tantra, this volume includes a lucid exposition of the meditative techniques of deity yoga from H.H. the Dalai Lama; the second and third chapters of the classic Great Exposition of Secret Mantra text; and a supplement by Jeffrey Hopkins outlining the structure of Action Tantra practices as well as the need for the development of special yogic powers.

Paperback

$27.95 - Paperback

in Volume III: Yoga Tantra the Dalai Lama details the practice of the next level of tantra, yoga tantra. With a preliminary overview of the motivation, His Holiness explains this level, which focuses on internal yoga, which here means the union of deity yoga with the wisdom of realizing emptiness. He details the yoga, both that with and that without signs, and then briefly explains how gaining stability in these practices is the foundation for some other practices that lead to mundane and extraordinary “feats.”

This work opens with the Dalai Lama presenting the key features of Yoga Tantra then continues with the root text by Tsongkhapa. This is followed by an overview of the central practices by Khaydrub Je. Jeffrey Hopkins concludes the volume with an outline of the steps of Yoga Tantra practice, which is drawn from the Dalai Lama’s, Tsongkhapa’s, and Khaydrub Je’s explanations.

An explanation of the highest yoga tantra is not included in these works, but an excellent resource is Daniel Cozort's Highest Yoga Tantra.

Paperback

$39.95 - Paperback

The Six Yogas of Naropa

Tsongkhapa's Commentary

By Glenn H. Mullin

Tsongkhapa's commentary entitled A Book of Three Inspirations: A Treatise on the Stages of Training in the Profound Path of Naro's Six Dharmas is commonly referred to as The Three Inspirations. Anyone who has read more than a few books on Tibetan Buddhism will have encountered references to the Six Yogas of Naropa, a preeminent yogic technology system. The six practices—inner heat, illusory body, clear light, consciousness transference, forceful projection, and bardo yoga—gradually came to pervade thousands of monasteries, nunneries, and hermitages throughout Central Asia over the past five and a half centuries.

Paperback

$27.95 - Paperback

The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa

By Glenn H. Mullin

Another text that is included in Tsongkhapa’s collected works is the short Practice Manual on the Six Yogas. This is included in the wider collection of texts on this practice titled The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa. Also included in this book are works by Tilopa, Naropa, Je Sherab Gyatso, and the First Panchen Lama.

From the Six Yogas of Naropa:

"Tsongkhapa's treatise on this system of tantric practice ... became the standard guide to the Naropa tradition at Ganden Monastery, the seat he founded near Lhasa in 1409. Ganden was to become the motherhouse of the Gelukpa school, and thus the symbolic head of the network of thousands of Gelukpa monasteries that sprang up over the succeeding centuries across Central Asia, from Siberia to northern India. A Book of Three Inspirations has served as the fundamental guide to Naropa's Six Yogas for the tens of thousands of Gelukpa monks, nuns, and lay practitioners throughout that vast area who were interested in pursuing the Naropa tradition as a personal tantric study. It has performed that function for almost six centuries now.

Tsongkhapa the Great's A Book of Three Inspirations has for centuries been regarded as special among the many. The text occupies a unique place in Tibetan tantric literature, for it in turn came to serve as the basis of hundreds of later treatments. His observations on various dimensions and implications of the Six Yogas became a launching pad for hundreds of later yogic writers, opening up new horizons on the practice and philosophy of the system. In particular, his work is treasured for its panoramic view of the Six Yogas, discussing each of the topics in relation to the bigger picture of tantric Buddhism, tracing each of the yogic practices to its source in an original tantra spoken by the Buddha, and presenting each within the context of the whole. His treatise is especially revered for the manner in which it discusses the first of the Six Yogas, that of the 'inner heat.' As His Holiness the present Dalai Lama put it at a public reading of and discourse upon the text in Dharamsala, India, in 1991, 'the work is regarded by Tibetans as tummo gyi gyalpo, the king of treatments on the inner heat yoga.' Few other Tibetan treatises match it in this respect."

Paperback | eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

This work has three main sections: an overview of Mahamudra, the First Panchen’s text The Main Road of the Triumphant Ones, and a commentary by the Dalai Lama. The author contextualizes the selection saying that the tradition of Mahamudra in the Gelug tradition comes through Tsongkhapa.

Other Notable Works Related to Tsongkhapa

Paperback | eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

Tibetan Literature

Studies in Genre

Edited by Jose Cabezon and Roger R. Jackson

Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre is a collection by leading Tibetologists. The immensity of Tibet's literary heritage, unsurprisingly, is filled with references to Tsongkhapa across a wide range of subjects. Just a sampling of them include: the establishment of the Gelug order; the monastic curriculum; debate manuals; establishment of Ganden; a comparison with Milarepa; the controversies about his views; a classification of his texts; and a lot more.

Paperback | eBook

$29.95 - Paperback

Mind in Tibetan Buddhism

By Lati Rinpoche, Edited and translated by Elizabeth Napper

Mind in Tibetan Buddhism is an oral commentary on Geshe Jampel Sampel's Presentation of Awareness and Knowledge Composite of All the Important Points, Opener of the Eye of New Intelligence. This topic, lorig in Tibetan, was not one on which Tsongkhapa wrote a dedicated text, but he does include it in an introduction to Dharmakirti’s Seven Treatises and one of his sections includes a brief presentation on lorig. Tsongkhapa is brought up throughout this book.

Tsongkhapa is also referenced in about 60 articles on shambhala.com, mostly from the Snow Lion newsletter archive.

Additional Resources

More can be found on Atisha's life on Treasury of Lives

The Thirteen Core Indian Buddhist Texts: A Reader's Guide

There are thirteen classics of Indian Mahayana philosophy, still used in Tibetan centers of education throughout Asia and beyond, particularly the Nyngma tradition, with overlap with the others. They cover the subjects of vinaya, abhidharma, Yogacara, Madhyamika, and the path of the Bodhisattva. They are some of the most frequently quoted texts found in works written from centuries ago to today. Below is a reader's guide to these works.

Khenpo Shenga, who penned influential commentaries on all 13 texts.

1. Pratimokṣha Sūtra

The first text is the Sutra for Individual Liberation or Sutra of the Discipline or Pratimokṣha Sūtra from the Buddha, containing all the precept for monastics. We have a commentary of the Bhiksuni Pratimoksha Sutra, Choosing Simplicity.

Related Books

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Thubten Chodron & Bhikshuni Jendy & Venerable Bhikshuni Master Wu Yin

2. The Vinayasutra by Gunaprabha

The second text is the Vinayasutra by Gunaprabha (7th century) who was a student of Vasubandhu. According to Ringu Tulku's The Ri-me Philosopy of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great, "Vasubandhu had many great students, and four of them were considered to be better than himself; Gunaprabha was the one who was better in the Vinaya. Gunaprabha put the four sections of the Vinaya into the proper order, and condensed the seventeen topics of the Vinaya into a shorter format; this is called the Vinaya Root Discourse. He wrote another text called the Discourse of One Hundred Actions, which gives practical instructions on activities related to the Vinaya."

3. The Compendium of Abhidharma or the Abhidharmasamuccaya by Asanga

This work on abhidharma does exist in a full, if somewhat dated English translation by Walpola Rahula. There is an excellent commentary on it by Traleg Rinpoche, published by KTD, Asangha's Abhidharmasamuccaya.

4. The Abhidharmakosha by Vasubandhu

Vasubhandu's Abhidharmakosha is the Hinayana treatise on abhidharma and is translated in Jewels from the Treasury which also includes the commentary by the Ninth Karmapa, Wangchuk Dorje.

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Thubten Chodron & Bhikshuni Jendy & Venerable Bhikshuni Master Wu Yin

5. The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way or Mulamadhyamakakarika

Nagarjuna most famous work, The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way or Mulamadhyamaka-karika is the first work on Madhyamyaka. The Root Stanzas holds an honored place in all branches of Tibetan Buddhism, as well as in the Buddhist traditions found in China, Japan, and Korea, because of the way it develops the seminal view of emptiness (shunyata), which is crucial to understanding Mahayana Buddhism and central to its practice.

The latest translation of the text, by the esteemed team of the Padmakara Translation Group, translated this for the occasion of His Holiness the Dalai Lama's visit to Dordogne, France. This version includes the Tibetan text.

In a concise presentation of this, its translator said, "It is important to see that in his explanations, or rather presentations, of the Middle Way, Nāgārjuna is formulating neither a religious doctrine nor a philosophical theory. He is not giving us yet another description of the world. He simply points to phenomena—the things of our experience that appear so vividly and function so effectively—and shows by force of reasoned argument that they cannot possibly exist in the way that they appear to exist, and that, in truth, they can be said neither to exist nor not to exist. Existence and nonexistence, however, form a perfect dichotomy. And since phenomena are said to lie in neither of these two ontological extremes, we are forced to the conclusion that their nature is ineffable. It cannot be spoken of or even conceived of. And yet it cannot be nothing—for how can anyone possibly deny the vivid experience of the phenomenal world? And thus we come to the nub of the question: How is the true nature of phenomena to be understood? How are we to lay hold of, or rather enter into, the kind of wisdom that, by revealing the emptiness of phenomena, is alone able to uproot our clinging to their apparent reality and thereby dissipate the tyrannical power that they have over us?"

The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way

$29.95 - Hardcover

By: Christine Downing & Heinrich Dumoulin & Nagarjuna & Padmakara Translation Group

6. The Introduction to the Middle Way or Madhyamakavatara

Chandrakirti's Introduction to the Middle Wayor Madhyamakavatara. This book includes a verse translation of the Madhyamakavatara by the renowned seventh-century Indian master Chandrakirti, an extremely influential text of Mahayana Buddhism, followed by an exhaustive logical explanation of its meaning by the modern Tibetan master Jamgön Mipham, composed approximately twelve centuries later. Chandrakirti's work is an introduction to the Madhyamika teachings of Nāgārjuna, which are themselves a systematization of the Prajnaparamita, or "Perfection of Wisdom" literature, the sutras on the crucial, but elusive concept of emptiness.

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group

7. The Four Hundred Stanzas or Chatuḥshataka Shastra

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzasor Chatuḥshataka shastra was written to explain how, according to Nāgārjuna, the practice of the stages of yogic deeds enables those with Mahayana motivation to attain Buddhahood. Both Nāgārjuna and Aryadeva urge those who want to understand reality to induce direct experience of ultimate truth through philosophic inquiry and reasoning.

Aryadeva's text is more than a commentary on Nāgārjuna's Treatise on the Middle Way because it also explains the extensive paths associated with conventional truths. The Four Hundred Stanzas is one of the fundamental works of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, and Gyel-tsap Je's commentary is arguably the most complete and important of the Tibetan commentaries on it.

Mahayana practitioners must eliminate not only obstructions to liberation, but also obstructions to the perfect knowledge of all phenomena. This requires a powerful understanding of selflessness, coupled with a vast accumulation of merit, or positive energy, resulting from the kind of love, compassion, and altruistic intention cultivated by bodhisattvas. The first half of the text focuses on the development of merit by showing how to correct distorted ideas about conventional reality and how to overcome disturbing emotions. The second half explains the nature of ultimate reality that all phenomena are empty of intrinsic existence. Gyel-tsap's commentary on Aryadeva's text takes the form of a lively dialogue that uses the words of Aryadeva to answer hypothetical and actual assertions questions and objections. Geshe Sonam Rinchen has provided additional commentary to the sections on conventional reality, elucidating their relevance for contemporary life.

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Aryadeva & Gyel-tsap & Geshe Sonam Rinchen

8. The Way of the Bodhisattva or Bodhicharyavatara

The Bodhicharyavatara, or The Way of the Bodhisattva, composed by the eighth-century Indian master Shantideva, has occupied an important place in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition throughout its history. It is a guide to cultivating the mind of enlightenment through generating the qualities of love, compassion, generosity, and patience.

We have a lot of resources on this site for this text - you can start with Way of the Bodhisattva Resource Page. In particular, we strongly recommend watching the immersive workshop from May of 2016 with esteemed translator Wulstan Fletcher who is part of the Padmakara Translation Group.

In addition, we have the famous commentary on this text, The Nectar of Manjusri's Speech. In this commentary, Kunzang Pelden has compiled the pith instructions of his teacher Patrul Rinpoche, the celebrated author of The Words of My Perfect Teacher.

$21.95 - Paperback

By: Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche & Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal & Patrul Rinpoche & Khenchen Palden Sherab

A Guide to The Words of My Perfect Teacher

$34.95 - Paperback

The Five Maitreya Texts

And then there are the five Maitreya texts that he imparted to Asanga. For an explanation of these texts see two of the foremost translators of them explain them in this pair of interviews with Karl Brunnnholzl and Thomas Doctor.

9. The Ornament of Clear Realization or Abhisamayalankara

The Abhisamayalamkara summarizes all the topics in the vast body of the Prajnaparamita Sutras. Resembling a zip-file, it comes to life only through its Indian and Tibetan commentaries. Together, these texts not only discuss the "hidden meaning" of the Prajnaparamita Sutras—the paths and bhumis of sravakas, pratyekabuddhas, and bodhisattvas—but also serve as contemplative manuals for the explicit topic of these sutras—emptiness—and how it is to be understood on the progressive levels of realization of bodhisattvas. Thus these texts describe what happens in the mind of a bodhisattva who meditates on emptiness, making it a living experience from the beginner's stage up through buddhahood.

Gone Beyondcontains the first in-depth study of the Abhisamayalamkara (the text studied most extensively in higher Tibetan Buddhist education) and its commentaries in the Kagyu School. This study (in two volumes) includes translations of Maitreya's famous text and its commentary by the Fifth Shamarpa Goncho Yenla (the first translation ever of a complete commentary on the Abhisamayalamkara into English), which are supplemented by extensive excerpts from the commentaries by the Third, Seventh, and Eighth Karmapas and others. Thus it closes a long-standing gap in the modern scholarship on the Prajnaparamita Sutras and the literature on paths and bhumis in Mahayana Buddhism.

Groundless Pathstakes the same material and looks at in the context of the Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. This study consists mainly of translations of Maitreya's famous text and two commentaries on it by Patrul Rinpoche. These are supplemented by three short texts on the paths and bhumis by the same author, as well as extensive excerpts from commentaries by six other Nyingma masters, including Mipham Rinpoche. Thus this book helps close a long-standing gap in the modern scholarship on the prajñaparamita sutras and the literature on paths and bhumis in Mahayana Buddhism.

10. Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sūtras or Mahayanasutralankara

The Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sūtrasor Mahayanasutralankara

The Ornament provides a comprehensive description of the bodhisattva’s view, meditation, and enlightened activities. Bodhisattvas are beings who, out of vast love for all sentient beings, have dedicated themselves to the task of becoming fully awakened buddhas, capable of helping all beings in innumerable and vast ways to become enlightened themselves. To fully awaken requires practicing great generosity, patience, energy, discipline, concentration, and wisdom, and Maitreya’s text explains what these enlightened qualities are and how to develop them.

This volume includes commentaries by Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham, whose discussions illuminate the subtleties of the root text and provide valuable insight into how to practice the way of the bodhisattva. Drawing on the Indian masters Vasubandhu and, in particular, Sthiramati, Mipham explains the Ornament with eloquence and brilliant clarity. This commentary is among his most treasured works.

Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sutras

$69.95 - Hardcover

By: Dharmachakra Translation Committee & Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Maitreya & Khenpo Shenga

11. Middle beyond Extremes or the Madhyāntavibhāga

Middle Beyond Extremes contains a translation of the Buddhist masterpiece Distinguishing the Middle from Extremes. This famed text, often referred to by its Sanskrit title, Madhyāntavibhāga, is part of a collection known as the Five Maitreya Teachings. Maitreya, the Buddha’s regent, is held to have entrusted these profound and vast instructions to the master Asaṅga in the heavenly realm of Tuṣita.

$22.95 - Paperback

By: Dharmachakra Translation Committee & Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Ju Mipham & Maitreya & Khenpo Shenga

12. Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature -Dharmadharmatavibhanga

We have three works that explore this text.

Outlining the difference between appearance and reality, Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature shows that the path to awakening involves leaving behind the inaccurate and limiting beliefs we have about ourselves and the world around us and opening ourselves to the limitless potential of our true nature. By divesting the mind of confusion, the treatise explains, we see things as they actually are. This insight allows for the natural unfolding of compassion and wisdom. This volume includes commentaries by Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham, whose discussions illuminate the subtleties of the root text and provide valuable insight into the nature of reality and the process of awakening.

Mining Wisdom from Delusion

The introduction of the book discusses these two topics (fundamental change and non-conceptual wisdom) at length and shows how they are treated in a number of other Buddhist scriptures. The three translated commentaries, by Vasubandhu, the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, and Gö Lotsāwa, as well as excerpts from all other available commentaries on Maitreya’s text, put it in the larger context of the Indian Yogācāra School and further clarify its main themes. They also show how this text is not a mere scholarly document, but an essential foundation for practicing both the sūtrayāna and the vajrayāna and thus making what it describes a living experience. The book also discusses the remaining four of the five works of Maitreya, their transmission from India to Tibet, and various views about them in the Tibetan tradition.

Distinguishing Phenomena and Pure Beingwas composed by Maitreya during the golden age of Indian Buddhism. Mipham's commentary supports Maitreya's text in a detailed analysis of how ordinary, confused consciousness can be transformed into wisdom. Easy-to-follow instructions guide the reader through the profound meditation that gradually brings about this transformation.

Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature

$24.95 - Hardcover

By: Dharmachakra Translation Committee & Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Ju Mipham & Maitreya & Khenpo Shenga

Mining for Wisdom within Delusion

$39.95 - Hardcover

By: Coleman Barks & Karl Brunnholzl & Asanga & Maitreya & Mohammad Ali Jamnia & The Third Karmapa

Maitreya's Distinguishing Phenomena and Pure Being

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Jim Scott

13. Treatise on the Sublime Continuum or the Uttaratantra Shastra

The Treatise on the Sublime Continuum or the Uttaratantra Shastra presents the Buddha's definitive teachings on how we should understand this ground of enlightenment and clarifies the nature and qualities of buddhahood. A major focus is “Buddha nature” (tathāgatagarbha), the innate potential in all living beings to become a fully awakened Buddha.

We have two books on this work.

The first is When the Clouds Part: The Uttaratantra and Its Meditative Tradition as a Bridge between Sutra and Tantra. This book discusses a wide range of topics connected with the notion of buddha nature as presented in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism and includes an overview of the sūtra sources of the tathāgatagarbha teachings and the different ways of explaining the meaning of this term. It includes new translations of the Maitreya treatise Mahāyānottaratantra (Ratnagotravibhāga), the primary Indian text on the subject, its Indian commentaries, and two (hitherto untranslated) commentaries from the Tibetan Kagyü tradition. Most important, the translator’s introduction investigates in detail the meditative tradition of using the Mahāyānottaratantra as a basis for Mahāmudrā instructions and the Shentong approach. This is supplemented by translations of a number of short Tibetan meditation manuals from the Kadampa, Kagyü, and Jonang schools that use the Mahāyānottaratantra as a work to contemplate and realize one’s own buddha nature.

The second title, Buddha Nature, includes commentaries by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye and Khenpo Tsultrim Gyatso.

$22.99 - eBook

By: Lenore Friedman & Rosemarie Fuchs & Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye & Keiko Matsui Gibson

And One More

As Georges Dreyfus notes in his The Sound of Two Hands Clapping, there is another core text that is often included in this group, for example at Namdroling: Shantarakshita's Adornment of the Middle Way including Mipham Rinpoche's commentary.

The Adornment of the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group & Shantarakshita

The Seventeen Panditas of Indian Buddhism

His Holiness the Dalai Lama has often said that Tibetan Buddhism is none other than the Buddhism of India in the tradition of Nalanda, the great center of Buddhist learning that was located in present-day Bihar, India.

Many of the greatest masters and scholars in Indian Buddhism resided-and often presided-at this monastic center of learning which in its heyday included thousands of monks, dozens of temples and an enormous library. While we do not know with certainty that all of the seventeen masters below physically stayed at Nalanda, there is no doubt that their teachings and impact became fully integrated into the teachings and presentations of Buddhist thought there.

Traditionally, Tibetans have referred to the Six Ornaments of India (Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Asanga, Vasubandhu, Dignaga, and Dharmakirti) and the Two Supreme Ones (Gunaprabha and Shakyaprabha).

The categorization of seventeen described below was put together by His Holiness and expands upon these eight. While it does not include some of the great Nalanda masters whose genius still resounds in Buddhist teachings throughout the world - Naropa, for example - it is an important list of the brilliant scholar - adepts whose innovations in explaining the truth that the Buddha revealed continue to benefit us today.

These seventeen masters are vitally important because their writings are all based on real meditative experience. Their legacy of texts and teachings that came out of this experience forms the very backbone of understanding that is the basis for establishing present day practitioners with the correct view that enables us to make progress on - and complete - the path to enlightenment.

Our Great Master's Series is a guide to the works of each master, with a focus on what is available from Shambhala and Snow Lion Publications, though we will include important works that our friends at Wisdom Publications, KTD, and others are publishing.

The order below has been changed from how it has been presented elsewhere to that of a more chronological one, which interestingly reveals how these great minds were often contemporaneous with each other and focused on very different areas of thought in Buddhist philosophy.

1. Nagarjuna is considered the first of the seventeen panditas of Nalanda. While Western scholars generally assume there were two Nagarjunas separated by several centuries, received tradition holds him as a long-lived master who was critical in revealing the Mahayana teachings and sutras, elucidating the meaning of emptiness and the Madhyamaka view in particular, and being a great master of tantra. His works are typically divided into three groups: his praises, his speeches, and works on reasoning. His most famous text is from the latter category; entitled Treatise on the Middle Way, it is translated in The Ornament of Reason.

2. Aryadeva (3rd century) was Nagarjuna's student and while many Western scholars once again identify two, the Tibetan tradition identifies him as a single master, active in the third century CE. At Nalanda, he was famous for converting many followers of brahminism to the Buddhist view. He is also said to be identical with one of the 84 mahasiddhas, Karnari. He is most famous for his Four Hundred Stanzas of the Middle Way which is a commentary on Nagarjuna's Treatise on the Middle Way that explains the paths associated with conventional truths.

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Aryadeva & Gyel-tsap & Geshe Sonam Rinchen

3. Asanga (320-390), born in present day Peshawar in Pakistan and the older brother of Vasubandu, he is often considered the father of Yogachara, though his texts cannot be so neatly categorized. While initially studying in the Sarvastivadin tradition, he adopted the view and practice of Mahayana. He spent 12 years in a cave, after which he had visions of Maitreya who brought him to Tushita heaven and gave him the teachings that form the five Maitreya texts. Other famous works include his commentary on Abhidharma from a Mahayana point of view as well as his Bodhisattva Paths and Bhumis and the Compendium of Mahayana.

4. Vasubandhu (4th century, possibly into the 5th), the brother of Asanga, is most famous for his Treasury of Abhidharma. Vasubandhu's classic short text on abhidharma, with commentary by Sthiramati has been translated by Artemus Engle in the book The Inner Science of Buddhist Practice: Vasubandhu's Summary of the Five Heaps with Commentary by Sthiramati, one of the most detailed presentations of mind and mental factors. He also presents Vasubandhu on Abhidharma in this short video discussing the skandhas, ayatanas, and dhatus, or in other words an explanation of what is presented in the Heart Sutra. Later, under the influence and guidance of Asanga, he adopted the view and practice of Mahayana.

5. Buddhapalita (470-540) is known as an early systematizer of what later writers termed the Prasangika Madhyamaka, which uses a technique of describing the absurd consequences of holding any view in an attempt to describe reality. While I am not aware of any complete translation of his works - which include a commentary on Nagaruna's Root Verses of the Middle Way - his ideas are succinctly encapsulated in the introduction of Introduction to the Middle Way.

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group

6. Dignaga (480-540) was a monk who was an early articulator of Buddhist logic, using syllogisms as a method for arriving at what he saw as the two types of valid cognition, that is, direct perception and inference. His most famous work is his Compendium of Valid Cognition and while a complete translation of this is not available in English, the ideas presented therein are explored in depth in Knowledge and Liberation and many other works.

7. Bhavaviveka (500-570 CE) is considered the godfather of what later writers term the Svatantrika Madhyamaka, in contrast to the Prasangika variant of which he was critical. His ideas are succinctly encapsulated in the introduction of Introduction to the Middle Way. While we are not aware of a complete English translation of this yet, his ideas are explored in depth in many works.

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group

8. Arya Vimuktisena (6th century), building on the work of Dignaga and later Madhyamaka teachers, wrote the first - and very important - commentary on the Ornament of Clear Realization (one of the Five Maitreya texts) that explicitly made the connection between it and the Perfection of Wisdom sutras. Link to video sharing: The Tibetan Commentaries on the Prajaparamita, Perfection of Wisdom.

9. Chandrakirti (600-650) built on the works of Nagarjuna and Buddhapalita, further elucidating them in his Introduction to the Middle Way. His work is the bedrock of the Prasangika viewpoint.

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group

10. Dharmakirti (600-670) built on the work of Dignaga and was a seminal figure in articulating what constitutes valid cognition. Dharmakirti argued that improvement of spiritual qualities were not limited by or to human nature. More can be read on this in the article Dharmakirti on Unlimited Spiritual Qualities. More can be read about Dharmakirti's theory of existance in the book Is Enlightenment Possible?: Dharmakirti and rGyal tshab rje on Knowledge, Rebirth, No-Self and Liberation by Roger Jackson, and by going to this published article.

11. Shantideva (8th century) is best known as the author of The Way of the Bodhisattva. For an article on Shantideva and his texts, see here.

12. Shantarakshita (725-788) was born into the royal house of Zahor in Bengal and became a great scholar at Nalanda who was later instrumental in establishing Buddhism in Tibet. His Adornment of the Middle Way is one of his more famous works. This work, later categorized as Yogachara Svatantrika Madhyamaka, builds on the work of his predecessors and presents what many consider to be one of the most important texts to study to receive the full and balanced understanding of how the various philosophical strains within Mahayana Buddhism coexist.

The Adornment of the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group & Shantarakshita