Related Reader's Guides

Guides to Nyingma Lineages: Dudjom Tersar | Longchen Nyingtig | Namcho & Palyul

Guides to Other Important Nyingma Figures: Rongzompa | Longchenpa | Jigme Lingpa | Patrul Rinpoche

Jose Ignacio Cabezon is the Fourteenth Dalai Lama Professor of Tibetan Buddhism and Cultural Studies at the University of California Santa Barbara. Formerly a Buddhist monk at Sera Monastery in South India, Professor Cabezón has authored a number of works on Tibetan literature, Buddhist philosophy, and sexuality. He is originally from Cuba and currently resides in California.

Edited by Jose Cabezon

Edited by Roger R. Jackson

By Leonard van der Kuijp

By James Burnell Robinson

By Paul Harrison

By Tadeusz Skorupski

By Jeffrey D. Schoening

By Joe B. Wilson

By Per Kvaerne

By Janet Gyatso

By Jeffrey Hopkins

By Shunzo Onoda

By Guy Newland

By Donald S. Lopez Jr.

By David Jackson

By Michael J. Sweet

By Jules B. Levinson

By Matthew Kapstein

By Yael Bentor

By John Makransky

By Daniel Cozort

By Jose Cabezon

By Geoffrey Samuel

By Roger R. Jackson

By Beth Newman

By P. C. Verhagen

By Rebecca Redwood French

By Todd Fenner

By Erberto Lo Bue

By John Newman

By Dan Martin

Jamgon Mipham Rinpoche: A Reader's Guide

Related Reader's Guides

Guides to Nyingma Lineages: Dudjom Tersar | Longchen Nyingtig | Namcho & Palyul

Guides to Other Important Nyingma Figures: Rongzompa | Longchenpa | Jigme Lingpa | Patrul Rinpoche

Mipham Rinpoche is a celebrated Nyingma scholar and practitioner. He is revered for being a prolific writer and for reinvigorating the Nyingma monastic university tradition with his commentaries on central Indian Buddhist texts including the Five Treaties of Maitreya, Chandrakirti's Introduction to the Middle Way, Shantarakshita's Adornment of the Middle Way, and his commentary on Shantideva's Wisdom Chapter. In addition, he is well known for his lengthly composition, The Epic of Gesar of Ling, which arose out of Tibet's oral tradition and is said to be equivalent to the Greek Iliad or the Odyssey. Lama Mipham was a student of the famed Nyingma master, Patrul Rinpoche, and was the principle teacher of Shechen Gyaltsap Rinpoche who went on to teach beloved teachers such as Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö.

Powerful in his striving and discernment,

A yogi [kusalī] of great learning and experience,

Who labored long in search of the deep meaning:

My great confederate, master Mipham...

-words of Lozang Rabsel from Lion of Speech: The Life of Mipham Rinpoche

$27.95 - Hardcover

Jamgön Mipham (1846–1912) is one of the great luminaries of Tibetan Buddhism in modern times. He has had a dominant and vitalizing influence on the Nyingma school in particular and, despite spending most of his life in retreat, is one of Tibet’s most prolific authors.

The first half of this volume comprises the first-ever English translation of the biography of Mipham Rinpoche written by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.

In keeping with the identification of Mipham as an emanation of Manjushri, the lion of speech, the second half comprises a selection of Mipham’s writings, designed to give the reader an experience of Mipham’s eloquent speech and incisive thought. It includes both a new translation of The Lion’s Roar: A Comprehensive Discourse on the Buddha-Nature and A Lamp to Dispel the Dark, a teaching of the Great Perfection, as well as excerpts from previously published translations of his works on Madhyamaka and tantra.

$34.95 - Paperback

Jamgön Mipam (1846–1912) is one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of Tibet. Monk, mystic, and brilliant philosopher, he shaped the trajectory of Tibetan Buddhism’s Nyingma school. This introduction provides a most concise entrée to this great luminary’s life and work. The first section gives a general context for understanding this remarkable individual who, though he spent the greater part of his life in solitary retreat, became one of the greatest scholars of his age. Part Two gives an overview of Mipam’s interpretation of Buddhism, examining his major themes, and devoting particular attention to his articulation of the Buddhist conception of emptiness. Part Three presents a representative sampling of Mipam’s writings.

Madhyamaka, or the Middle Way, is founded on the idea that all phenomena are empty of an inherent, unchanging, and permanent ‘nature.’ Nagarjuna, believed to be the first proponent of Madhyamaka, identified two aspects of truth: the relative, being the functional aspect of the phenomenal world, and the ultimate, which is beyond conventions and mental elaboration.

$32.95 - Paperback

Introduction to the Middle Way presents an adventure into the heart of Buddhist wisdom through the Madhyamika, or "middle way," teachings, which are designed to take the ordinary intellect to the limit of its powers and then show that there is more.

This book includes a verse translation of the Madhyamakavatara by the renowned seventh-century Indian master Chandrakirti, an extremely influential text of Mahayana Buddhism, followed by an exhaustive logical explanation of its meaning by the modern Tibetan master Jamgön Mipham, composed approximately twelve centuries later. Chandrakirti's work is an introduction to the Madhyamika teachings of Nagarjuna, which are themselves a systematization of the Prajnaparamita, or "Perfection of Wisdom" literature, the sutras on the crucial but elusive concept of emptiness.

$39.95 - Paperback

In the Madhyamakalankara, Shantarakshita synthesized the views of Madhyamaka and Yogachara, the two great streams of Mahayana Buddhism. This was the last great philosophical development of Buddhist India.

In his brilliant and searching commentary, Mipham re-presented Shantarakshita to a world that had largely forgotten him, defending his position and showing how it should be understood in relation to the teaching of Chandrakirti. To do this, he subtly reassessed the Svatantrika-Prasangika distinction, thereby clarifying and rehabilitating Yogachara-Madhyamaka as a bridge whereby the highest philosophical view on the sutra level flows naturally into the view of tantra. Mipham’s commentary has with reason been described as one of the most profound examinations of Madhyamaka ever written.

$29.95 - Paperback

$39.95 - Hardcover

Shāntideva’s guide to the training of a Bodhisattva is one of the most important and beloved texts in the Tibetan tradition. The ninth chapter, however, dealing with Madhyamaka, the Middle Way, the most profound wisdom view of Mahayana Buddhism, has always posed unique challenges to readers. This commentary by the great scholar Mipham Rinpoche presents in quite straightforward terms Shantideva’s exposition of emptiness, the essential foundation of all Buddhist doctrine, demonstrating that it is not only compatible with, but in fact crucial to, the correct understanding of other important Buddhist teachings such as karma, rebirth, and the practice of compassion. Mipham interprets Shāntideva according to the view of the Nyingma school, which in some respects was at variance with the religiously and politically dominant interpretation of the text in Tibet at that time. As a result, his commentary stirred up a furious debate. With the addition of a critique of Mipham Rinpoche’s view by a prominent scholar of the time, along with Mipham’s response, that debate is beautifully captured in this volume.

These works are part of a collection known as the Five Maitreya Teachings, a set of philosophical works that have become classics of the Indian Buddhist tradition. Maitreya, the Buddha’s regent, is held to have entrusted these profound and vast instructions to the master Asaṅga in the heavenly realm of Tuṣita.

$22.95 - Paperback

Middle Beyond Extremes contains a translation of the Buddhist masterpiece Distinguishing the Middle from Extremes. This famed text, often referred to by its Sanskrit title, Madhyantavibhaga, is part of a collection known as the Five Maitreya Teachings. Maitreya is held to have entrusted these profound and vast instructions to the master Asanga in the heavenly realm of Tusita.

Distinguishing the Middle from Extremes employs the principle of the three natures to explain the way things seem to be as well as the way they actually are. It is presented here alongside commentaries by two outstanding masters of Tibet’s nonsectarian Rimé movement, Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham.

$18.95 - Paperback

The Buddhist masterpiece Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature, often referred to by its Sanskrit title, Dharmadharmatāvibhanga, is part of a collection known as the Five Maitreya Teachings, a set of philosophical works that have become classics of the Indian Buddhist tradition. Maitreya, the Buddha's regent, is held to have entrusted these profound and vast instructions to the master Asanga in the heavenly realm of Tusita. By divesting the mind of confusion, the treatise explains, we see things as they actually are. This insight allows for the natural unfolding of compassion and wisdom. This volume includes commentaries by Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham, whose discussions illuminate the subtleties of the root text and provide valuable insight into the nature of reality and the process of awakening.

$69.95 - Hardcover

The Buddhist masterpiece Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sūtras, often referred to by its Sanskrit title, Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra, is part of a collection known as the Five Maitreya Teachings, a set of philosophical works that have become classics of the Indian Buddhist tradition. Maitreya, the Buddha’s regent, is held to have entrusted these profound and vast instructions to the master Asaṅga in the heavenly realm of Tuṣita.

The Ornament provides a comprehensive description of the bodhisattva’s view, meditation, and enlightened activities. Bodhisattvas are beings who, out of vast love for all sentient beings, have dedicated themselves to the task of becoming fully awakened buddhas, capable of helping all beings in innumerable and vast ways to become enlightened themselves. To fully awaken requires practicing great generosity, patience, energy, discipline, concentration, and wisdom, and Maitreya’s text explains what these enlightened qualities are and how to develop them.

$24.95 - Paperback

Distinguishing Phenomena and Pure Being was composed by Maitreya during the golden age of Indian Buddhism. Mipham's commentary supports Maitreya's text in a detailed analysis of how ordinary, confused consciousness can be transformed into wisdom. Easy-to-follow instructions guide the reader through the profound meditation that gradually brings about this transformation. This important and comprehensive work belongs on the bookshelf of any serious Buddhist practitioner—and indeed of anyone interested in realizing their full potential as a human being.

Listen to Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche teach on the Ornament of the Mahayana Sutras

Stephen Gethin from the Padmakara Translation Group discusses his translation of A Feast of the Nectar of the Supreme Vehicle, Mipham RInpoche's commentary on the Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sutras Mahayanasutralamkara.

$69.95 - Hardcover

A monumental work and Indian Buddhist classic, the Ornament of the Mahāyāna Sūtras (Mahāyānasūtrālamkāra) is a precious resource for students wishing to study in-depth the philosophy and path of Mahāyāna Buddhism. This full translation and commentary outlines the importance of Mahāyāna, the centrality of bodhicitta or the mind of awakening, the path of becoming a bodhisattva, and how one can save beings from suffering through skillful means.

An interview with Sangye Khandro and Lama Chonam on the creation and relevance of this landmark translation of The Epic of Gesar.

The epic of Gesar has been the national treasure of Tibet for almost a thousand years. An open canon of tales about a superhuman warrior-king, the epic is still a living oral tradition, included on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This book is a translation of the beginning portion of this enormous corpus that Mipham Rinpoche compiled.

Born in the pure lands the son of two wisdom deities, Gesar takes rebirth in the human realm in order to defeat the demon kings who had taken over the empires of Asia and to thus liberate the people from suffering. His jealous uncle Trothung proves to be the first major threat to this goal, but Gesar outwits him every time using magic. In the last chapters of the book, he and Trothung’s son face off in a high-tension horse race to decide who will win the throne of Ling and the hand of the coveted Princess Drugmo in marriage.

Gesar’s story is popularly read as an allegory, with Gesar representing the ideal of spiritual warriorship—that is, fearlessness in the face of obstacles on the path to enlightenment. Just as Gesar rides his flying steed, we too can ride the energy of our inherent dignity, confidence, and strength, subduing inner demons and claiming victory.

Born in the pure lands the son of two wisdom deities, Gesar takes rebirth in the human realm in order to defeat the demon kings who had taken over the empires of Asia and to thus liberate the people from suffering. His jealous uncle Trothung proves to be the first major threat to this goal, but Gesar outwits him every time using magic. In the last chapters of the book, he and Trothung’s son face off in a high-tension horse race to decide who will win the throne of Ling and the hand of the coveted Princess Drugmo in marriage.

$39.95 - Paperback

This volume recounts stories of Gesar fending off demons and liberating his foes as an enlightened leader. While the first three volumes cover Gesar’s birth, youth, and rise to power, this volume recounts the martial victories and magical feats that made him a legendary figure in Tibet and beyond.

A Garland of Views presents both a concise commentary by the eighth-century Indian Buddhist master Padmasambhava on a chapter from the Guhyagarbha Tantra on the different Buddhist and non-Buddhist philosophical views, including the Great Perfection (Dzogchen), and an explicative commentary on Padmasambhava’s text by the nineteenth-century scholar Jamgön Mipham (1846–1912).

Padmasambhava’s text is a core text of the Nyingma tradition because it provides the basis for the system of nine vehicles (three sutra vehicles and six tantra vehicles) that subsequently became the accepted way of classifying the different Buddhist paths in the Nyingma tradition.

Mipham’s commentary is the one most commonly used to explain Padmasambhava’s teaching. Mipham is well known for his prolific, lucid, and original writings on many subjects, including science, medicine, and philosophy, in addition to Tibetan Buddhist practice and theory.

$24.95 - Paperback

Leadership. Power. Responsibility. From Sun Tzu to Plato to Machiavelli, sages east and west have advised kings and rulers on how to lead. Their motivations and techniques have varied, but one thing they have in common is that the relevance of their advice has reached far beyond the few individuals to whom they were originally addressing. Over the centuries, millions have read their works and continue to be inspired by their teachings.

The nineteenth-century Buddhist monk and luminary Jamgön Mipham’s letter to the king of Dergé, whose small kingdom straddled China and Tibet during a particularly turbulent period, is similar in the universality of its message. This work, however, is unique in that it stresses compassion, impartiality, self-control, and virtue as essential for long-lasting success—whether as a leader or an individual trying to live a meaningful life. Mipham’s historic contribution to ethics and governance, until now little studied outside of Buddhist circles, teaches us the importance of protecting life, implementing fair taxation, supporting environmental sustainability, aiding the poor, and safeguarding freedom of religion. Both present-day leaders and those they lead will find this classic work, finally available in English, profoundly illuminating on political, societal, and personal levels.

$24.95 - Paperback

The Tibetan divination system called "Mo" has been relied upon for centuries to give insight into the future turns of events, undertakings, and relationships. It is a clear and simple method involving two rolls of a die to reveal one of the thirty-six possible outcomes described in the text. This Mo, which obtains its power from Manjushri, was developed by the great master Jamgön Mipham from sacred texts expounded by the Buddha.

Mipham Rinpoche's Beacon of Certainty, a very important text used by Nyingma monastic colleges, includes an in-depth treatment of Madhyamaka, tantra, and Dzogchen.

He also wrote a song expressing the view of Dzogchen which Thrangu Rinpoche uses to illustrate the unitty of the paprroaches of Dzogchen, Mahamudra and Madhyamaka in Harmony of Views: Three Songs by Ju Mipham, Changkya Rolpay Dorje, and Chögyam Trungpa.

Fundamental Mind , which also includes a sixteen-page biography of Mipham Rinpoche by Khetsun Sangpo Rinpoche, consists of the first volume of his trilogy called the Three Cycles of Fundamental Mind, a Nyingma text on ultimate reality that emphasizes the introduction of fundamental mind through a lama's instructions.

There are also a few selections contained in other books, including In Praise of Dharmadhatu by Nagarjuna with commentary by the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje. This book contains a few selections by Mipham Rinpoche. In the first, from his Exposition of the Madhyamakalamkara, he emphasizes the critical importance of directly connecting with the experience of Dzogchen by first gaining certainty in primordial purity-otherwise one ends up with a view that will get one nowhere.

In Straight from the Heart there is a short teaching which is a pith instruction on Mahamudra

In Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light, Chapter 10 consists of a short Dzogchen text by Mipham Rinpoche on the nature of mind entitled The Quintessential Instructions of Mind: The Buddha No Farther Than One's Palm.

Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light

$19.95 - Paperback

$21.95 - Paperback

By: Khenchen Thrangu & Thrangu Dharmakara Translation Collaborative

$18.95 - Paperback

By: Jamgon Mipham & Jeffrey Hopkins & Mi-pam-gya-tso & Khetsun Sangpo Rinpoche

Mipham Rinpoche's work on Tantra is also very extensive. His main work in English is his commentary on the Guhyagarbha Tantra, which is the essence of the eighteen Mahayoga tantras. There are two translations of this: The Essence of Clear Light, which includes the Tibetan, and Luminous Essence. For this text, it is really important that they be read by those who have received the initiation and have permission and guidance from a qualified teacher specifically for this text. By all accounts, there is no point to read these without having completed the proper preparation.

In White Lotus: An Explanation of the Seven-Line Prayer to Guru Padmasambhava, he gives a detailed explanation of this foundational prayer, explaining to us how to understand it according to its many layers of meaning.

$18.95 - Paperback

$95.00 - Hardcover

By: Lama Chonam & Jamgon Mipham & Ju Mipham & Sangye Khandro

$34.95 - Hardcover

By: Dharmachakra Translation Committee & H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Jamgon Mipham

Two other works include wonderful pieces by Mipham Rinpoche that we should mention. As mentioned above, he really reinvigorated the Nyingma tradition during a time when there were many critics who did not properly understand it. The Ri-me Philosophy of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great: A Study of the Buddhist Lineages of Tibet includes a scathing eight-page rebuttal of critics of the Nyingma tantras.

A short but extremely moving prayer by Mipham Rinpoche in praise to Yeshe Tsogyal called The Longing Melody on Faith is included in Thinley Norbu Rinpoche's masterpiece on ngondro, or the preliminary practices, A Cascading Waterfall of Nectar.

Mipham Rinpoche also wrote a short text on the Treasure tradition entitled The Gem that Clears the Waters: An Investigation of Treasure Revealers, in which he presents a funny, honest look at the terma tradition. This is included in Tibetan Treasure Literature.

Mipham Rinpoche is central to the curriculum at the vast Buddhist community of Larung Gar, founded by His Holiness Jigme Phuntsok Rinpoche. It is therefore no surprise to find Mipham RInpoche's work throughout the 2021 release of Voices from Larung Gar: Shaping Tibetan Buddhism for the Twenty-First Century. In particular, there is a translation of Mipham Rinpoche's Wangdu, Great Clouds of Blessings: The Prayer That Magnetizes All that Appears and All That Exists. This is a practice that is credited for making Larung Gar the important center that it remains to this day. Khenpo Sodargye provides a detailed explanation of this magnetizing practice over thirty pages, the benefits of which he describes as follows:

"By relying on the prayer, one gains, in the outer sense, the ability to benefit all living beings, while its inner effect offers one the ability to control discursive thoughts and thereby attain full control of the body and the mind."

In Ruby Rosary, Kyabje Thinley Norbu Rinpoche quotes Mipham Rinpoche at length - over eight pages, describing the life and impact of Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo (Rongzom Mahapandita).

"The teachings of the Early Translation school constituted the principal practice of the Great Rongzom. In particular, all the Secret Mantra teachings of the Early Translation school—the instructions given by Padmasambhava, Vimalamitra, Vairotsana, and others—were contained within and transmitted to Rongzompa. His main practice was the Nyingma teachings. He mastered the approach and accomplishment of Mātaraḥ, Yamarāja, and Vajrakīla, and with this power he subjugated all the gods and demons of the eight classes throughout Tibet, who offered him their life essence."

There are many other books where Mipham Rinpoche's work and influence is discussed.

There are many other books where Mipham Rinpoche's work and influence is discussed.

Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre refers to his contributions to the Gesar epic, his book on how to prepare colors, ink, and gold for thangka painting, as well as his vast contributions to philosophical literature.

The recently released anthology by Matthieu Richard, On the Path to Enlightenment, has four short pieces by Mipham Rinpoche.

The Buddhist Psychology of Awakening (to be published in 2019 by Shambhala) also contains an evaluation of his contribution to the understanding of Abhidharma.

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Jose Cabezon & Rebecca Redwood French & Jamgon Mipham & Roger R. Jackson & Per Kvaerne

In his remarkable book Incarnation, Tulku Thondop Rinpoche says:

This great scholar and adept said, at the time of his passing, "After this life, I will never take rebirth in this mundane world. I will remain only in pure lands. However, because of the power of aspirations, it is natural that the display of my tulkus as the Noble Ones will appear as long as samsara remains. " When people urged him to live longer, he said, "I certainly will not live. I will not take rebirth either. I am going to Shambhala in the North. "

But his legacy is very much with us today, directly through his teachings and the many masters who continue to pass them on in the East and West.

In Brilliant Moon, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, who was one of the most influential teachers of our generation, talks about Mipham Rinpoche throughout, with over 170 references to him.

It is no surprise that Mipham Rinpoche's teachings continue to appear in the written and oral teachings of many contemporary teachers. As one example in many, Khenpo Garwang's recently released Your Mind Is Your Teacher is a detailed instruction on contemplative or analytical meditation based on Mipham Rinpoche's Wheel of Analytical Meditation.

We look forward to seeing more and more of Mipham Rinpoche's material to be published in English in the coming years.

$39.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche & Ani Jinba Palmo & Shechen Rabjam

Check out more reader guides on Tibetan Buddhism!

And for Tibetan readers, TBRC/BDRC of course provides downloadable pdfs of Mipham Rinpoche's works in Tibetan

| The following article is from the Spring, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Contributions to the Study of Buddhism and Tibet In Honor of Jeffrey Hopkins

This is a book offered in tribute to Jeffrey Hopkins by colleagues and former students. Jeffrey Hopkins has, in his sixty years, made profound and diverse contributions to the understanding of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism in the West. In his collaborations with the Dalai Lama, such as Kindness, Clarity, and Insight, and in books like Tibetan Arts of Love and Emptiness Yoga, Hopkins has reached out to the general reader, making the wisdom of Tibet accessible to every one. Yet there is never anything superficial about his work; his recent Emptiness in the Mind-Only School is a magisterial display of painstaking scholarly work.

Changing Minds contains essays that reflect the breadth and influence of Hopkins.

The following is an excerpt from the Editor's Introduction.

Twenty-five years ago I first met Jeffrey Hopkins as my instructor in a popular undergraduate course on Buddhist meditation at the University of Virginia. 1 liked the course and studied with him for almost thirteen yearsbecause of the way Hopkins presented Buddhist ideas. He did not posture as the authoritative curator of a mummified body of knowledge. He did not mystify the tradition and he certainly did not act as a missionary for it. On the other hand, he did not attempt to account for Buddhism in terms of any extrinsic academic ideology. Instead, Hopkins was interested in encountering Buddhist worldviews as living systems of human meaning; his classes were invitations to participate in that encoimter. They were based on his own meticulous translations of primary-source Tibetan or Sanskrit texts, sometimes produced in collaboration with Tibetan colleagues. The message that I got, from his teaching and his books, was: There are and long have been real people, whole communities and civilizations, for whom the ideas and texts we are now studying are profoundly important. We should show them the respect of taking their ideas seriously. That means finding out how far we can go in understanding how others make sense of the worldand seeing how our minds change in the process.

Hopkins presented Tibetan Buddhism as a living system of meaning in part by bringing to campus distinguished Tibetan scholars from the refugee communities of India. At that time, in the middle of the 1970s, this was something quite rare; most of my fellow undergraduates had heard the term Dalai Lama only as a Johnny Carson punch-line. Sometimes a monk would accompany Hopkins to class and speak to us in Tibetan, with Hopkins translating. Hopkins taught many undergraduate and graduate courses in this way while I was at the University of Virginia. There is no doubt that the presence of visiting Tibetan scholars on campus greatly enriched my education in the graduate Buddhist Studies program. Instead of having only Hopkins representing and mediating Tibetan Buddhism to us, we had continuing opportunities to work with scholars whose credentials to speak from within and on behalf of the tradition were unimpeachable. Some graduate students in the program likely developed, outside of class, spiritual connections with these lamas that were deeper and more important to them than their academic relationship with Hopkins.

That was not my experience; I was not drawn into the program mainly by the Tibetan scholars. After all, they could not speak English and only Hopkins and the more advanced graduate students could really question them directly. For me, the heart of the program was Hopkins. He had no superficial flash as a public speaker, but he had intellectual substance and passion. He conveyed his prodigious learning with an intensity that John Buescher conjures from the past in the opening article of this volume. Buescher gives us Hopkins at workguiding students through the complexities of Sanskrit syntax, teaching them how to pull from the tangle something that would change their minds:

It's the self of persons and of things

that we're looking for, Jeffrey said, as he pointed to Nagarj una's text in front of him. The tiling that seems to cover over them and make them a whole, single entity, assembling things out of their parts. We've got to take them apart to see it. Parsing the words of the text, then translating them, the operation became unexpectedly exacting. Sweat rolled down in tight, little streams under my shirt. We were unprepared for this drill, this scalpel. Jeffrey, however, proceeded on, laying bare our ignorance, peremptorily rejecting any uncertain or wrong answer. As he thundered his demand for the right answer, we searched for it. We desperately wished we could find it, some seat of the soul, some little treasure amid the remains of the words that now lay in pieces all about us.

Did these teaching methods leave room for students to challenge the tradition itself, to form their own critical evaluation of it? In my undergraduate courses with Hopkins, he seemed to regard it as satisfactory if a student could think through some of the complexities of Tibetan Buddhist doctrine. He certainly did not forbid etic analysis or independent critique, but he did little to encourage it. This might not seem ideal, but it did not strike me as so different from many other courses that I had taken, in Russian literature, Greek tragedy, or experimental psychology, for example. In each case, the premise was that there is a very complicated, very unfamiliar story to be told. The novice must expect to spend time on the ground of the storyteller, learning the story well and getting the details straight, before launching an idiosyncratic metanar- rative on what the story (in this case someone else's religion) is really about.

As a graduate student, my experience was that Hopkins wanted even demandedwork that was not only intimately grounded in the details of the tradition, but also had something to say, something useful or insightful. As I gained mastery of a research topic (and not before), he clearly expected more of me than a re-transmission of what learned lamas had said. For example, he told me that my seminar paper on the Abhisamayalamkara was boring because it simply reorganized information from the tradition. On another occasion, Hopkins asked me to present a paper in an interdepartmental colloquium series, assigning me a topic from the work of the Sa skya scholar sTag tshang. I decided on my own that I would instead give a psychoanalytic treatment of Tsong kha pa on the three principal aspects of the path. When he heard my talk, rather than being upset that I had presumed to offer an independent analysis, he was clearly pleased. The same was true when I submitted my dissertation; when I used various Western theories to give an independent account of the religiosity of dGe lugs scholasticism, Hopkins's criticisms were aimed only at strengthening my argument.

Hopkins's scholarship likewise evidences concern to avoid arrogant pseudo-objectivity on the one hand and naive adulation on the other. Hopkins has taken special pains to avoid the first of these extremes and has been more careful in that regard than some. By being open in his appreciation for some aspects of the traditions he studies, Hopkins has at times chosen to risk appearing to some as an academic front-man for religious dogma. In books such as Meditation on Emptiness and The Tantric Distinction, Buddhist thought-systems are not specimens to be dissected at arm's length. Instead, Hopkins recreates his encounter with another world of meaning, a very particular and intricate Asian Buddhist world which can never again be imagined as completely separate from our world. Describing his version of a methodological middle way, Hopkins writes that his aim is to evince a respect for the directions, goals, and horizons of the culture itself without swallowing an Asian tradition as if it had all the answers or...pretending to have a privileged position.

* * *

Don Lopez and Joe Wilson conceived that this book should come into being to honor Jeffrey Hopkins in his sixtieth year. At their suggestion and with the encouragement of Anne Klein, I undertook the project, soliciting contributions only from a close circle of Hopkins's friends, admirers, and former students. Then, with some assistance from Snow Lion and outside readers, I selected the articles in this volume for publication. As Paul Hackett shows in the closing article of this volume, Hopkins's research has covered a wide range of concerns, centering on dGe lugs scholarship but ranging far beyond it in several directions. A thin cross-section of that diversity is reflected in the scholarship here.

Describing his version I of a methodological middle way, Hopkins writes that his aim is to evince a respect for the directions, goals, and horizons of the culture itself without t swallowing an Asian tradition as if it had all the answers or... pretending to have a privileged position.

John Buescher opens our volume with an atmospheric and evocative real-life detective story. Caught in the act of teaching Madhyamika Buddhism, Hopkins appears as a philosophical sleuth on the trail of truth. Buescher then weaves into this portrait its unexpected resonances, years later, in a baffling international news-eventthe sudden appearance of a previously unknown dental relic of the Buddha.

The Madhyamika theme continues through the next two articles, by Guy Newland and Donald Lopez. My article is inspired in part by the efforts of Hopkins to describe the Madhyamika view for a general readership. I summarize some of the philosophical claims Tsong kha makes in Lam rim chen mo, reflecting in particular on the notion of conventional reality. Lopez's piece distills a careful synopsis of Tsong kha pa's treatment of the object of negation (dgag bya) in Madhyamika analysis. Then, based on his own new translations, he treats us to a riveting critique of this position by the brilliant twentieth-century iconoclast, dGe dun Chos phel.

Contributions by Dan Cozort and Elizabeth Napper keep the focus on Tsong kha pa and his Lam rim chen mo, but move away from Madhyamika Cozort provides a useful, clear, and detailed analysis of Tsong kha pa on the special dangers of anger, which is said to cut the roots of virtue. What, exactly, does this mean? How deep is the damage of anger? Cozort finds Tsong kha pa working with mixed success to explicate this doctrine and integrate it into his system. Like Cozort, Napper scrutinizes Lam rim chen mo in her contribution, Ethics as the Basis of a Tantric Tradition: Tsong kha pa and the Founding of the dGe lugs Order in Tibet. She lays out exactly how Tsong kha pa used his sources, subtly and skillfully reshaping grammar, nuance, and context in order to build a new and unique system of religious meaning. She concludes with some frank observations about the impact that the distinctive features of this system (such as its emphasis on monastic ethics) have had on the later tradition. Nap- per's impeccable work, synthesizing insights from many years of work with Lam rim chen mo and its sources, merits the appreciation of everyone who studies the dGe lugs order.

The next pair of articles shift our attention to the contemplative traditions of rDzogs chen and Mahamudra. Anne Klein takes us into the realm of Bon rDzogs chen poetry. Her original translations gracefully depict a natural, open awarenessunrecognized by ordinary personsin which reality is experienced as spontaneous and unbounded wholeness. She carefully explains who reads such poetry, to what end, and she compares the handling of contradiction and nonduality in Buddhist Madhyamika with that in Bon rDzogs chen. Roger Jackson then gives us an outstanding treatment of a little- known topic, the tradition of dGe lugs Mahamudra (phyag rgya chen po). As he notes, Mahamudra is more usually associated with meditative practices central to the bKa' brgyud tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. Questions about the role of and basis for a dGe lugs form of Mahamudra lead Jackson to broader insights about inter-sectarian connections.

As Hopkins suggests, our understanding of early dGe lugs has been much aided by recent advances in our grasp on the teachings of Shes rab rgyal mtshan and the Jo nang other emptiness doctrine. Here we offer two articles which touch on this issue, demonstrating how the self-empty vs. other-empty controversy set the stage for otherwise disparate debates. Displaying his formidable knowledge of Tibetan Perfection of Wisdom literature, Gareth Sparham shows how debates about the authorship and authority of key commentaries evolved within the context of controversy between dGe lugs and Jo nang views. Then, Joe Wilson gives us a generous and cogent explication of how and why the concept of a basis-of-all (alay- avijnana, kun gzhi rnam par shes pa) is subject to radically different constructions in the Jo nang and dGe lugs traditions.

While cross-cultural and comparative themes are touched upon in other contributions, Jose Cabezon and Harvey Aronson bring them into focus. Cabezon analyzes the structure and content of Tibetan colophons, looking for evidence of an implicit theory of authorship and literary production. Simplistic notions of authorship are quickly problema- tized by the multiple layers of productivity through which a book is generated. Cabezon has given us a unique and nuanced study, full of allusions to and connections with the conversations of Western literary theory. Such cross-cultural comparison arises from historical contact; in the case of Tibetan Buddhism, that contact includes the unprecedented phenomenon of large numbers of Westerners taking up Buddhist practices and striving to embody Buddhist virtues. Using object-relations theory and his own experience as a clinician, Harvey Aronson warns of the pathological pitfalls that may afflict the self-sacrificing American bodhisattva, but argues for a model of healthy altruism.

Our volume concludes with Paul Hackett's comprehensive survey of the published works of Jeffrey Hopkins. We are grateful to Hackett for an ambitious essay charting the range and depth of Hopkins's oeuvre. Inasmuch as Hopkins's recently published Emptiness in the Mind-Only School has been hailed by many as his best work ever, and inasmuch as it is the first of a tliree-volume series, Hackett's work will perhaps but serve as a starting point for future bibliographic analysis.

In sum, this volume is presented as a tribute to the work of Jeffrey Hopkins as a teacher and as a scholar. Paul Hackett has written eloquently of Hopkins's impact:

Most people who have pursued knowledge and learning would be hard pressed not to remember at least one teacher sometime, somewhere, who first inspired them and instilled in them a sense of value in learning. This ability, the capacity not only to convey meaning, but also to motivate remains an art which stands apart from mere erudition. For some, it comes naturally; for others it requires effort; though in each person who manages to master it, there is always evident an idiosyncratic artistry by which their knowledge and experience is conveyed. So it is with Jeffrey Hopkins, who has repeatedly demonstrated not only his depth of knowledge, but also his skill as a teacher and writer.

As we see in this volume, he has inspired and enlivened us in many different ways. So now we say: Thank you!

| The following article is from the Summer, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

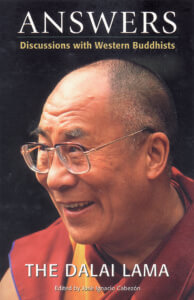

"THIS IS A GREAT BOOK! The richness of this book lies in its simple spontaneity and breadth of subject matter." —The Tibet Journal

By H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Translated by Jose Cabezon

Edited by Jose Cabezon

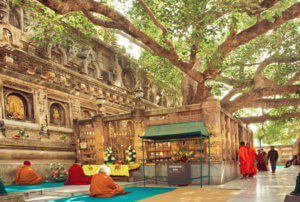

In India, at the place where the Buddha attained enlightenment, it became a well-established tradition for the Dalai Lama to spend several days each year giving teachings to Buddhists from all over the world.

Following his teachings, he held informal group discussions with Western students of Buddhism. In these lively exchanges, the Dalai Lama exhibits clear and penetrating insight into issues that are most important to Western students.

Some of the topics discussed are: psychology, Christianity, being a practicing Buddhist in the West, spiritual teachers, reincarnation, emptiness, tantra, protector deities, liberation, meditation, compassion, disciplining others, the power of holy places, and retreats.

Jose Ignacio Cabezon holds the Dalai Lama XIV Chair in Tibetan Buddhism and Cultural Studies in the Religious Studies Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara and is the author of A Dose of Emptiness.

The following is an excerpt from the Editor's Introduction to "Answers":

Over the past several years, it has become a well established tradition for His Holiness the Dalai Lama to spend several days in January or February in residence in Bodhgaya. During this time, Buddhists from all over the world gather to listen to the teachings of His Holiness and to share in days of prayer and meditation.

Especially for the Tibetan Buddhists in exile, for the thousands who flock from Tibet for this occasion, and for the Indian Buddhists from the border areas of Ladakh, Kunu, Arunachal Pradesh and so forth, it is an opportunity not only to make pilgrimage to the place of the Buddha's enlightenment, to pray and to make prostrations under the Bodhi tree, and to circumambulate the central temple, it is an opportunity to engage in all of these practices during the visit of the Dalai Lama, who for them and for thousands of other Buddhists throughout the world, is a source of inspiration and the embodiment of living and active Buddhist principles.

For the community of Western Buddhists as well, winter in Bodhgaya is a time for rejoicing, meeting old friends, and especially for practicing mental cultivation. Several meditation courses meet during this time, and there is usually some form of translation available for those who wish to attend the teachings of His Holiness. In addition, beginning in 1981, His Holiness has given group interviews to the Westerners.

Sometimes the discussions, which invariably have taken the form of question and answer sessions, were granted to groups at the close of a meditation retreat and were restricted to those who participated in that retreat (as in the case with the second discussion in this collection).

The majority of the meetings, however, were open to the general public. They were held, almost exclusively, in the Tibetan Temple in Bodhgaya.

Because of the spontaneous and dialogical nature of the interviews, they tended to differ in mood and content from year to year. Still, they all share one common quality: that the questions asked are topical, the issues dealt with reflecting the current concerns of the participants, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist.

In a very real way, the questions raised bring up problems that all of us face today. The range of topics is vast. We find philosophical discussions of the doctrine of emptiness, questions concerning the role of monks and nuns in the world today, and debates concerning particle physics, not to speak of questions dealing with politics, psychology, and Tantra.

In short, within these few pages, we find the entire gamut of religious and secular human concerns.

I myself was present at the first discussion and was the translator for the fourth. I have witnessed through the years the uniqueness of these occasions, and so, when I was approached to bring out that year's discussion in published form, I realized how worthwhile it would be to compile the Bodhgaya discussions in a single volume.

To this end, I have gone through tapes of all of the discussions, have scrutinized all portions in which His Holiness spoke in Tibetan to insure accuracy and to avoid the types of omissions to which spontaneous translation is heir. I have, of course, edited the entire text.

Nonetheless, with a view to preserving the original flavor of the dialogues as much as possible, I have tried to keep editing to a minimum.

Here are some selected questions and answers from the book:

QUESTIONER: But aren't the objects of Tantric meditation just imaginary things without any reality?

HIS HOLINESS: Certainly, at the outset these objects are just mind-created.

In the beginning of the practice the various objects one realizes are simply imaginary. Nonetheless, they serve a special function and each has a specific purpose.

Their being imaginary does not deprive them of efficacy.

Q: How do things exist if they are empty of inherent existence?

HIS HOLINESS: The doctrines of emptiness and selflessness do not imply the non-existence of things. Things do exist.

When we say that all phenomena are void of self-existence, it does not mean that we are advocating non-existence, that we are repudiating that things exist.

Then what is it we are negating? We are negating, or denying, that anything exists from its own side without depending on other things.

Hence, it is because things depend for their existence upon other causes and conditions that they are said to lack independent self-existence.

To put it another way, if we search for an object, subjecting it to logical analysis, it cannot be found. Whatever the object may be, whether it is mental or physical, whether it is nirvana or Sakyamuni Buddha himself, nothing can ever be found when it is searched for, when it is subjected to logical inquiry.

Now you see, we have this belief in an "I." We say, "I am so and so" or "I am a Buddhist."

If we investigate the implications of this, we cannot but conclude that the self, or "I," exists. Where there is a belief, there must be a believer, so there must be sentient beings. There is no question whether or not there exist beings—of course beings exist.

The Dalai Lama exists. Tibetans exist. There are Canadians and there are the English. Since England exists, there must be Englishmen, and an English language.

This is what we are speaking now. That there are beings who are at present speaking English is a fact which no one can deny.

But if we now ask ourselves, "where is this English which we are all speaking?," "where are the Englishmen?,' "where is the I'?," "where is the self of the Dalai Lama?"

We might be tempted to say that because no self is to be found when analyzed with logical reasoning, that there is no self at all. But this is wrong.

We can, for example, point to the Dalai Lama's physical form, his body, and we know that the Dalai Lama has a mind. My body and mind belong to me. So if I didn't exist at all, then how could "I" be the "owner' of my body and mind? How could they be "mine"? The body and mind belong to someone, and that someone is the "I."

It is because the body belongs to the self that, when we take an aspirin and the body feels better, we say, "I feel better." So it is because it is meaningful to say "I am not well" when the body is not well, it is because we sometimes get angry with ourselves when our mind forgets something and we say, "Oh, I'm so absent-minded," it is because all of these situations and forms of expression do occur and are meaningful, that we know there must exist a conventional, or nominal, "I."

Now, apart from the body and mind, there can be no "I," and yet, if we search for the self among our mental and physical aggregates, there is no "I" to be found. So the point is this:

there is an "I"

but it is something that is merely labeled in dependence upon

the body and mind.

Now the body itself is something which is material, and it is an entity composed of many parts, and it too, if searched for among those parts, cannot be found.

This applies equally to all phenomena, even to Maitreya Buddha himself. If we look for Maitreya Buddha among his aggregates, we cannot find even him. Since ultimately even Buddhas do not exist, we know that ultimately there can be no person, or self, of any kind.

However, conventionally, there is a Maitreya Buddha. His statue or image we can see for ourselves here in the temple. Now again, let us consider the image. It has different parts: the head, the torso, the hands, and feet. Apart from these there is no "image of Maitreya Buddha." The image is simply a composite of these different parts labeled by the name image of Maitreya Buddha.

So the conclusion is this:

if we investigate and search for any object,

we could spend years and years and never find it.

This means that the image of Maitreya, for example, does not exist from its own side.

It is something that is only labeled by our minds.

It does not exist inherently, and so it must be an entity only imputed, or labeled, by the mind.

Though the image does not ultimately exist, nonetheless, if we take the image as our object in visualization, for example, and worship it, etc., the merit is accrued and benefit will come.

Q: Can you explain how Tantric meditation achieves the enlightened state so much more quickly than vipasyana, i.e. insight meditation?

HIS HOLINESS: In Tantric meditation, particularly in the practice of Anuttarayoga Tantra, while one is realizing emptiness, the ultimate truth, one controls thought through the use of certain techniques.

In the Sutrayana, the non-Tantric form of the Mahayana, there is no mention of these unique techniques involving the yogic practices of controlled breathing and meditation using the inner channels and chakras, etc. The Sutrayana just describes how to analyze the object, i.e. how to come to gain insight into the nature of the object through reasoning, etc.

The Anuttarayoga Tantra, however, teaches, in addition to this, certain techniques which use the channels, subtle winds, etc. to help one to control one's thoughts more effectively. These methods help one to more quickly gain control over the scattered mind and to achieve more effectively a level of consciousness which is at once subtle and powerful. This is the basis of the system.

The wisdom that realizes emptiness, that has gained insight into the nature of reality, is of varying kinds, depending upon the level of subtlety of the consciousness perceiving the emptiness.

In general, there are rough levels of consciousness, more subtle levels, and then the innermost subtle level of consciousness. It is the uncommon characteristic of Tantric practice that through it one can evoke this most subtle consciousness at will and put it to use in a most effective way.

For example, when emptiness is realized by this subtlest level of mind, it is more powerful, having a much greater effect on the personality.

In order to activate or make use of the more subtle levels of consciousness, it is necessary to block the rougher levels—the rougher or grosser levels must cease.

It is through specifically Tantric practices, such as the meditations on the chakras and the channels (nadis), that one can control and temporarily abandon the rougher levels of consciousness. When these become suppressed, the subtler levels of consciousness become active. And it is through the use of the subtlest level of consciousness that the most powerful spiritual realizations can come about.

Hence, it is through the Tantric practice involving the most subtle consciousness that the goal of enlightenment can most quickly be realized.

Q: It is generally said that teachers of other religions, no matter how great, cannot attain liberation without turning to the Buddhist path.

Now suppose there is a great teacher, say he is a Saivite, and suppose he upholds very strict discipline and is totally dedicated to other people all of the time, always giving himself. Is this person, simply because he follows Siva, incapable of attaining liberation, and if so, what can be done to help him?

HIS HOLINESS: During the Buddha's own time, there were many non-Buddhist teachers whom the Buddha could not help, for whom he could do nothing. So he just let them be.

The Buddha Sakyamuni was an extraordinary being, he was the manifestation, the nirmanakaya, or physical appearance, of an already enlightened being.

But while some people recognized him as a Buddha, other regarded him as a black magician with strange and evil powers. So, you see, even the Buddha Sakyamuni himself was not accepted as an enlightened being by all of his contemporaries.

Different human beings have different mental predispositions, and there are cases when even Buddha himself could not do much to overcome these—there was a limit.

Now today, the followers of Siva have their own religious practices, and they reap some benefit from engaging in their own forms of worship. Through this, their life will gradually change.

Now my own position on this question is that Siva-ji's followers should practice according to their own beliefs and traditions, Christians must genuinely and sincerely follow what they believe, and so forth. That is sufficient.

Q: But they will, not attain liberation.

HIS HOLINESS: We Buddhists ourselves will not be liberated at once. In our own case, it will take time.

Gradually, we will be able to reach moksa, or nirvana, but the majority of Buddhists will not achieve this within their own lifetimes. So there's no hurry.

If Buddhists themselves have to wait, perhaps many lifetimes, for their goal, why should we expect that it be different for non-Buddhists? So, you see, nothing much can be done.

Suppose, for example, you try to convert someone from another religion to the Buddhist religion, and you argue with them trying to convince them of the inferiority of their position. And suppose you do not succeed, suppose they do not become Buddhist. On the one hand, you have failed in your task, and on the other hand, you may have weakened the trust they have in their own religion, so that they may come to doubt their own faith. What have you accomplished by all this?

It is of no use. When we come into contact with the followers of different religions, we should not argue. Instead, we should advise them to follow their own beliefs as sincerely and as truthfully as possible.

For if they do so, they will no doubt reap certain benefits. Of this there is no doubt. Even in the immediate future, they will be able to achieve more happiness and more satisfaction. Do you agree?

This is the way I usually act in such matters, it is my belief. When I meet the followers of different religions, I always praise them, for it is enough, it is sufficient, that they are following the moral teachings that are emphasized in every religion.

It is enough, as I mentioned earlier, that they are trying to become better human beings. This in itself is very good and worthy of praise.

For more information:

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is considered the foremost Buddhist leader of our time. The exiled spiritual head of the Tibetan people, he is a Nobel Peace Laureate, a Congressional Gold Medal recipient, and a remarkable teacher and scholar who has authored over one hundred books.

Kindness, Clarity, and Insight

$16.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & John Blofeld & Kathrin Asper & Katsuki Sekida

$21.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Padmakara Translation Group