Les Fehmi

A pioneer in the field of neurofeedback, Les Fehmi, PhD, BCIA-EEG, was director of the Princeton Biofeedback Centre in Princeton, New Jersey. He held an MA and PhD in psychology from UCLA and completed his post-doctoral fellowship at UCLA’s Brain Research Institute. An affiliate member of the Department of Medicine at Princeton University Medical Center, for over four decades Dr. Fehmi was active as a psychologist in private practice, a speaker, and an author in peer-reviewed journals. A certified “speed-and-explosion specialist,” Dr. Fehmi worked with the Dallas Cowboys, the New Jersey Nets, and the Olympic Development Committee. He also served as a consultant for Harvard’s Massachusetts General Hospital, the Johnson & Johnson corporation, and the Veterans Administration.

Les Fehmi

GUIDES

Finding Rest Through the Open-Focus Method

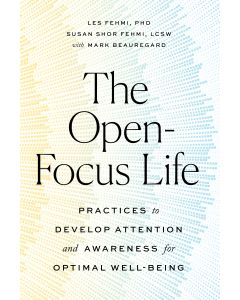

An excerpt from The Open-Focus Life

The clock shows three o’clock in the morning. It’s a night like many others, when you can’t fall asleep, or you drift off for an hour and then wake up in a panic about something you can’t remember, chasing endless worries.

Now you’re thinking about work again, worrying about how you’re going to get the money to pay that bill, the stupid argument you had on Facebook with someone you don’t even know about something you don’t really care about. Where is that barking dog? Does one of your neighbors have a new dog?

The meditation book said you should observe the thoughts without following them, just notice the thoughts that you’re having without participating in them, but even when you’ve managed to do that for a few moments, the thoughts have popped back up again, and the more worrisome thoughts suck you right back in. Melatonin works sometimes, tryptophan works sometimes, chamomile tea—but now you’re just thinking about all the sleep remedies that don’t work instead of actually sleeping. If only you’d had time to get to the gym today—and now you’re beating yourself up about all the things you should have done differently throughout the day, or throughout your whole life. You wonder if you should get up and take a sleeping pill—but then your mind will be shrouded in a thick fog when you have to get up for work four hours from now. Why are these anxious thoughts plaguing you? Where do they come from?

An even better question would be: Where are these thoughts right now?

The psychological term for thoughts is “mental representations,” and they occur mainly in your brain. But what about that stress you feel about the bills, that vague stomachache, the worry about your insurance? What about your changing moods as you struggle to fall asleep—are they “mental representations” as well? Partly, but neuroscientists have been able to determine that different moods produce and are caused by different chemical reactions that occur all over your body. Modern science in many ways confirms the folk wisdom we developed as a culture over the course of thousands of years: what we perceive as sadness, for example, occurs simultaneously in our brains and in chemical changes in and around our hearts, which is why sadness gives rise to words like “heartsick,” “heartache,” and “heartbreak.” Emotions like stress are associated with the biochemistry of the stomach (an irritating encounter can be “gut-wrenching”; a stressful situation can give you “butterflies in your stomach”), and fear and anger are associated with nerves in the lower parts of the digestive system, which find expression in vulgar sayings that represent the taboos associated with those volatile emotions (you can get “pissed off,” for example, and really “lose your shit”). These mental representations or thoughts that are keeping you awake are happening in your brain, and they’re also occurring throughout your body. Locating them in your brain and also in your body, in the space that your brain and body occupy, is the first step in really inhabiting your thoughts and feelings, really becoming one with them.

You might ask: Why would I want to become one with my unpleasant thoughts and emotions? Because they’re already part of you, and the fact that they are keeping you awake means that you are separating yourself from them, that you are paying attention to them in a way that distances you from your feelings and makes them painful. Your attention on them has become too narrow and objective, and instead of seeming like part of you, they have come to seem different from you, to seem like they’re happening to you—but in reality, they are not separate from you. They are occurring in your body, in the space that you physically occupy, and paying attention to them as part of your physical space, integrating them into your body, is the secret to calming them and falling asleep.

If you are feeling stress and worry about a relationship, for example, try imagining the distance between your brain and your heart, where that anxiety can reside. Can you imagine the space between your ears, where your worried thoughts are occurring?

Imagine that space in your head where your thoughts are going on. When you have imagined that space, between your ears, behind your eyes, then imagine the distance between that space and the space that your heart occupies. While you keep imagining the distance between your brain and your heart, can you also imagine the space between your heart and your stomach, where the adrenalin of your worries is constricting your blood vessels and causing what can be a churning feeling? Can you feel that space in and around your stomach? Allow yourself to feel it, however intense it might be. Now imagine the distance between your stomach and your heart again. Your heart is beating. Notice your breathing, how the breath coming in and out of your nose and mouth, your throat and lungs, can show you the rate of your heart. Can you imagine the distance between your heart and your jaw? Now imagine the distance between your jaw and the space between your eyes. Can you imagine connecting that space that contains your eyes, your mouth, and your jaw to the space in your throat and down to your heart?

Your worried thoughts are part of your body and the space that your body occupies, and your body is just a small part of the space in your room.

As you imagine the distance between your head and your heart, between your heart and your stomach, can you imagine at the same time becoming aware of your lower organs? Can you imagine also including the space that your hips and legs and feet occupy?

When you imagine the space that your body occupies, you are also imagining the true nature of your thoughts, which are physical processes occurring in physical space. Now, can you imagine the distance between your feet and the bedroom wall? And between the wall nearest your feet and the wall nearest your head? Can you imagine connecting the space between those two walls through your body, which includes your feet and your hands, your stomach, your heart, your jaw, and your eyes?

When you feel your anxious thoughts as fully part of your body and become one with them, as you truly are, your worries will become what they really are—just another part of the space that is your body, lying atop the space that is your bed. Between the walls of your bedroom, there is nothing but space, including your body—the space where you lie, comfortably. Now, can you imagine the distance between the top of your head and the soles of your feet, including your heart and your stomach and your lower organs, your arms and your legs? And can you imagine the space all around your body, on every side, including above you and below you? Take a moment to do this, to connect all of these spaces in your imagination just as they’re actually connected in physical reality.

The thoughts flowing through your body are part of this space. Can you imagine your thoughts as just a tiny part of the space that is your body and an even smaller part of the space that is this room and an even smaller part of the space all around your room? Can you imagine your thoughts as a tiny part of the whole physical world around you—above, below, and on every side of you? Close your eyes and let your thoughts be the tiny part of this space that they really are and that you really are. Allow yourself to be the physical space within you and all around you.

Share

Related Books