Patricia Donegan, the great poet, translator, and promoter of haiku, died on Tuesday, January 24th at 6:20pm CST. Her friend Elaine Martin shared the following:

"During a recent visit with her brother she stated, 'I go willingly into the sound of the crickets.' Amazing that she uttered such words while moving between confusion, anxiety, and limited lucidity. She never stopped writing her poetry.

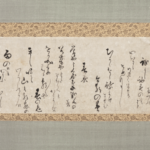

Anyone who has the Vajradhatu 1980 Vajrayana Seminary Transcripts can enjoy the exchange of poetry between Patricia and Vidyadhara Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche that follows many of those talks. "

Patricia was a faculty member of East-West poetics at Naropa University under Allen Ginsberg and Chögyam Trungpa; a student of Japanese haiku master Seishi Yamaguchi; and a Fulbright scholar to Japan. She is a meditation teacher, the poetry editor for Kyoto Journal, and a member of the Haiku Society of America. Her haiku works include Haiku Mind: 108 Poems to Cultivate Awareness and Open Your Heart, Chiyo-ni: Woman Haiku Master (co-translated with Yoshie Ishibashi), and Haiku: Asian Arts for Creative Kids. Her poetry collections include Without Warning, Bone Poems, and Hot Haiku.

A new book of hers, an extraordinary collection of haiku and her elucidations, will be released in 2024 by Shambhala Publications.

The following haiku and Patricia's accompanying discussion are from Haiku Mind: 108 Poems to Cultivate Awareness and Open Your Heart