Perle Besserman

A descendant of the Baal Shem Tov, Perle Besserman has studied Jewish mysticism with Rabbis Zvi Yehuda Kook and Aryeh Kaplan. She has written several books on mysticism, including Kabbalah: The Way of the Jewish Mystic (published under the name Perle Epstein), and is the editor of an anthology in the Shambhala Pocket Classics series, The Way of the Jewish Mystics. She presents workshops on women's spirituality around the United States and in Europe.

Perle Besserman

A descendant of the Baal Shem Tov, Perle Besserman has studied Jewish mysticism with Rabbis Zvi Yehuda Kook and Aryeh Kaplan. She has written several books on mysticism, including Kabbalah: The Way of the Jewish Mystic (published under the name Perle Epstein), and is the editor of an anthology in the Shambhala Pocket Classics series, The Way of the Jewish Mystics. She presents workshops on women's spirituality around the United States and in Europe.

GUIDES

The Path of Spheres | An Excerpt from Kabbalah

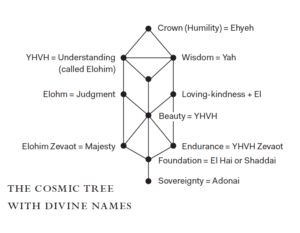

Since the Middle Ages the cosmic tree of life with its ten spheres, or divine attributes, has been the central image of kabbalistic meditation. Though some masters adapted the “seven heavens” of the first century Merkabah mystics, equating them with the seven lower branches of the tree, most Kabbalists focused their attention on the symbolic tree alone. With its inner “lights,” corresponding colors, metals, and divine names, the tree itself was complicated enough. The mystic’s attitude as he approached meditation on the spheres proved him to be as certain of his ultimate goal as he was reverential. Says Moses de Leon, a thirteenth-century Spanish Kabbalist:

When God gave the Torah to Israel, He opened the seven heavens to them, and they saw that nothing was there in reality but His Glory; He opened the seven worlds to them and they saw that nothing was there but His Glory; He opened the seven abysses before their eyes, and they saw that nothing was there but His Glory. Meditate on these things and you will understand that God’s essence is linked and connected with all worlds, and that all forms of existence are linked and connected with each other, but derived from His existence and essence.*

* Quoted in Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, p. 223

In this spirit, the mystic prepared to scale the tree, confront the worlds, acknowledge the links through his own person, and come to a direct experience of the divine ground on which the whole scheme rests.

“When I open the book Zohar,” said the Baal Shem Tov, “I behold the whole universe.”

The sphere of Sovereignty represents our world of matter. Foundation, Endurance, and Majesty combine as the premanifest world of spirit. Beauty, Loving-kindness, and Judgment form the world of creation. While the world of Wisdom, Understanding, and Crown is the very domain of divine immanence. Thus, in “climbing” mentally toward his source, the mystic traverses the myriad universes embodied in the ten spheres, as well as the four archetypal worlds, the seventy divine names, and innumerable “faces” on the tree. The culmination of all devotional, contemplative, and visionary works alluding to this ascent—the guide book of guide books—is the Zohar, or “Book of Splendor.” A massive compendium of stories and biblical exegesis, this book both decoded the esoteric Torah and presented the devotee with a detailed map of the visionary landscape he would be exploring along the tree. “When I open the book Zohar,” said the Baal Shem Tov, “I behold the whole universe.” And he meant it literally.

Rabbi Simeon Bar Yohai and the “Zohar”

Scholars, on the other hand, call the Zohar a brilliant forgery devised by Moses de Leon, who, they say, attributed the work to the great Tannaitic sages in an attempt to legitimize it. Forgery or no, the Zohar is indispensable to an understanding of Jewish mystical life from the Middle Ages to our own times. The background of the book is well known: Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai, its hero, was a second-century sage who, accompanied by his son Eleazar, lived in a cave for thirteen years to escape the Romans who had killed his master, Rabbi Akiva. Miraculously sustained by a carob tree and a fountain, which both sprang up at the mouth of their cave, the father and son sat buried in sand all day in order to protect themselves from the scorching sun that shines on the area that is now occupied by the Ben-Gurion Airport in Lod (Lydda), Israel. Here they studied the Torah under the guidance of the prophet Elijah. In the thirteenth year of their exile, the Roman emperor Trajan, their principal persecutor, died, leaving the two sages free to emerge from hiding. Horrified at the lack of spirituality he encountered among the Jews on his return, Rabbi Simeon returned to his cave to meditate for another year. At the end of that period a voice resounded through the cave, urging him to leave ordinary men to their own devices and to teach only those who were ready to hear him. The discourses given by Rabbi Simeon at the urging of that divine order—recorded by the loyal group of “companions” who gathered round him on his second re-emergence into the world—comprise the Zohar.

Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai apparently belonged to that small group of gifted teachers whose mere presence could transform spiritually any man, woman, child, or animal. He taught that all observable things here were reflected in a higher world and that no thing or person survived independently on any plane of existence, no matter how high. Anyone determined to elevate his own soul was therefore automatically committing himself to elevate every sentient, and even insentient, entity in God’s creation. “All souls form but one unity with the Divine Soul,” was the basis for all his teachings. The entire aim of a man’s stay on earth, said Rabbi Simeon, is to realize this in the experience of union:

All things of which this world is composed, as the soul and the body, will return to the principle and to the root from which they sprang. For God is the beginning and He is the end of all the degrees of creation. And all the degrees are bound with Hisseal. He is the unique Being, in spite of the innumerable forms in which He is clothed.

Rabbi Simeon’s message is therefore a call to union with the Divine. In his view even the written and spoken Torah are actually One, since they emerge directly from the revelation at Sinai, where God’s words were each divided into seventy sounds which appeared in the form of seventy lights that enabled the Israelites to see the words as they heard them. Similarly, the spheres, also emanations from the One, provide the Kabbalist with the opportunity to relive the Sinai mystery in his meditations. More than mere rungs on a ladder, the divine attributes actualize the otherwise physically imperceptible notion of God. So closely intertwined are these attributes with the very words of the Torah that they are virtually interchangeable for purposes of contemplation. When seen in this light, the divine attributes (which are themselves interchangeable) resound with the hidden Names which God assigned to Himself.

The egoless heart of the mystic radiates these illumined names and is simultaneously absorbed by them. Rabbi Simeon taught many forms of meditation on the spheres. One example of the multiple possibilities he expounded was to imagine the attributes as a series of dancing lights against the branches of the tree. Closing his eyes, the Kabbalist visualized them vibrating with color, blazing with the letters of the divine names, each one reflecting its corresponding metal, planet, angel, and human body part. He gazed until the lights began to shift positions; one mounting on the left; one descending on the right; one entering between them. Two spheres crown themselves with a third; three merge into one; one suddenly emanates many colors. Then six spheres descend all at once, doubling to twelve. Twelve become twenty-two, then six again, and then ten. At last, all the spheres are swallowed up in one.

The human breath is a mixture of subtle elements comprised of air, fire, and water. Without breath we die.

Although there is a definite resemblance between this mental exercise and certain drug-induced experiences of light, color, and movement, we ought not assume that Rabbi Simeon and his companions were transporting themselves with hallucinogens. All evidence points to a strict pattern of mental concentration in an alert state heightened by nothing more than fasting, perhaps, and isolation.

The parts of the Kabbalist’s body, too, are alive with knowledge. The seven lower spheres on the tree correspond to seven centers of heavenly power disbursed along the spine. Meditation on the spine reveals that a human being is composed of male (active, fiery) energy on the right, and female (receptive, watery) on the left. Thus, says Rabbi Simeon, in observing and combining the two qualities, the disciple actually experiences the unifying principle of creation directly: “In the form of God He made him, male and female He made them” (Genesis 1:27). Furthermore, the seven lower spheres by which the transcendent Absolute is comprehensible to man all share human neural counterparts which, like the spheres along the tree, meet in the highest center located in the brain. Rabbi Simeon refers metaphorically to the crown of the head as “the Brooks of God,” and, reminding his companions of The Song of Songs, asks: “What is this ‘fountain of gardens, a well of living waters, flowing from Lebanon? It is nothing more than the sphere representing Wisdom.” And since the word “Lebanon” comes from the same root as laban, “white,” Solomon also here means it to represent the “white matter in the brain.” In Rabbi Simeon’s hands, the entire verse becomes an esoteric lesson in contemplation:

Come with me from Lebanon, bride, with me from Lebanon! Look from the top of Amana, from the top of Senir and Hermon, from the lion’s dens, from the mountains of the leopards.

Breath and sound emerge from the white matter in the human brain, here called “Lebanon.” “Amana” is the throat, which projects the breath from the topmost nerve center of the body and allows it to circulate downward to the lower nerve centers along the spine. The top of “Senir” and “Hermon” represent the tongue; the “lion’s den,” the teeth; the “mountains of the leopards,” the lips and speech.

King Solomon’s Breathing Exercise

Solomon, gifted in speech and song, devised this contemplative exercise, says Rabbi Simeon, as a result of his own ecstatic experiences. Having attained to the seventh sphere on the tree, he condensed the mystic ascent into three books for those who would follow. The Song of Songs therefore represents the nature of the sphere known as Beauty; Ecclesiastes depicts the sphere of Judgment; and Proverbs characterizes Loving-kindness. Solomon’s father David, also a poet, transmitted to him the technique for evoking the “holy breath,” or inspiration, which induced the visionary experiences and, ultimately, the three great books. Says Rabbi Simeon, “the human breath is a mixture of subtle elements comprised of air, fire, and water. Without breath we die.

By learning and practicing the secrets inherent in the breath, Solomon could lift nature’s physical veil from created things and see the spirit within.” What is usually translated in Ecclesiastes as “vanity” (hebli) may therefore be read esoterically as: “I have seen all things in the days of my breath, hebel.” In some as yet undisclosed way, Rabbi Simeon taught Solomon’s technique of directing attention to the white matter in the brain while altering normal breathing patterns. Insisting that union between man and God “is best effected on earth” through the vehicle of breath, he likened the mystery of breathing to the sacred Shema, the daily declaration of God’s unity with His Name. Rabbi Simeon pointed out that the three names contained in the blessing—YHVH, Elohaynu, YHVH—signify the fire, air, and water of the human breath. Visualizing the three highest attributes on the tree (Crown, Wisdom, and Understanding) as he recites the declaration, the Kabbalist makes of his own breath a channel for the divine influx. “Whilst a man’s mouth and lips are moving his heart and will must soar to the height of heights, so as to acknowledge the unity of the whole.”

Share

Related Books