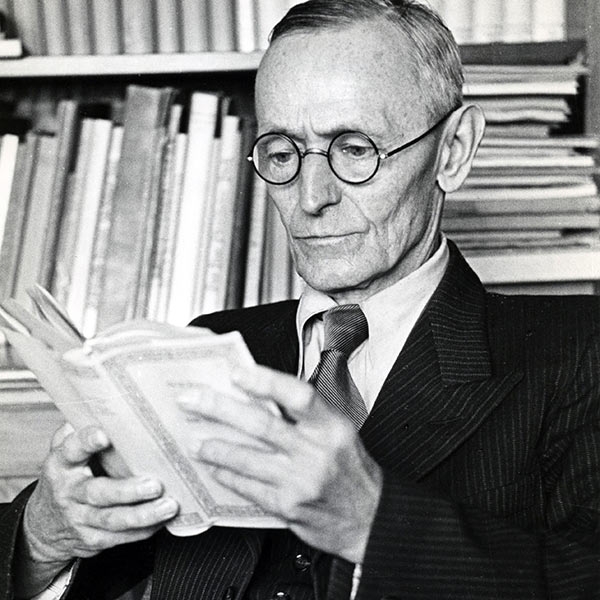

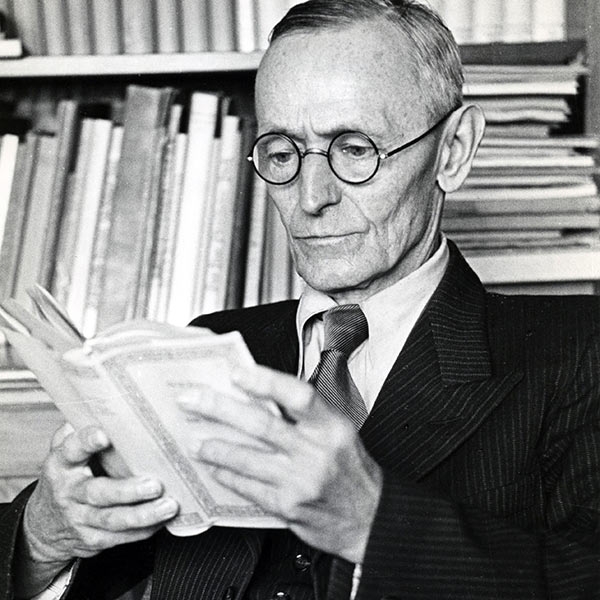

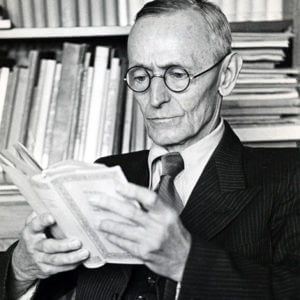

Hermann Hesse

Hermann Hesse was born in 1877 in Calw, Germany. He was the son and grandson of Protestant missionaries and was educated in religious schools until the age of thirteen, when he dropped out of school. At age eighteen he moved to Basel, Switzerland, to work as a bookseller and lived in Switzerland for most of his life. His early novels include Peter Camenzind (1904), Beneath the Wheel (1906), Gertrud (1910), and Rosshalde (1914). During this period Hesse married and had three sons.

During World War I Hesse worked to supply German prisoners of war with reading materials and expressed his pacifist leanings in antiwar tracts and novels. Hesse’s lifelong battles with depression drew him to study Freud during this period and, later, to undergo analysis with Jung. His first major literary success was the novel Demian (1919). When Hesse’s first marriage ended, he moved to Montagnola, Switzerland, where he created his best-known works: Siddhartha (1922), Steppenwolf (1927), Narcissus and Goldmund (1930), Journey to the East (1932), and The Glass Bead Game (1943). Hesse won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946. He died in 1962 at the age of eighty-five.

Hermann Hesse

Hermann Hesse was born in 1877 in Calw, Germany. He was the son and grandson of Protestant missionaries and was educated in religious schools until the age of thirteen, when he dropped out of school. At age eighteen he moved to Basel, Switzerland, to work as a bookseller and lived in Switzerland for most of his life. His early novels include Peter Camenzind (1904), Beneath the Wheel (1906), Gertrud (1910), and Rosshalde (1914). During this period Hesse married and had three sons.

During World War I Hesse worked to supply German prisoners of war with reading materials and expressed his pacifist leanings in antiwar tracts and novels. Hesse’s lifelong battles with depression drew him to study Freud during this period and, later, to undergo analysis with Jung. His first major literary success was the novel Demian (1919). When Hesse’s first marriage ended, he moved to Montagnola, Switzerland, where he created his best-known works: Siddhartha (1922), Steppenwolf (1927), Narcissus and Goldmund (1930), Journey to the East (1932), and The Glass Bead Game (1943). Hesse won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946. He died in 1962 at the age of eighty-five.

-

Singapore Dream and Other Adventures$21.95- Paperback

Singapore Dream and Other Adventures$21.95- PaperbackBy Hermann Hesse

Translated by Sherab Chodzin Kohn -

Siddhartha$24.95- Digital Audio

Siddhartha$24.95- Digital AudioTranslated by Sherab Chodzin Kohn

Read by Baron Christian

By Hermann Hesse

GUIDES

Singapore Dream | An Excerpt from Singapore Dream & Other Adventures

In the morning I had chased butterflies on the byways, overgrown with grass and overhung with foliage, that run among the European gardens. In the white heat of noon I returned to the city on foot, and I passed the afternoon walking about, visiting shops, and doing my shopping in the beautiful, lively, teeming streets of Singapore. Now I was sitting in the high, pillared salon of the hotel eating supper with my traveling companion. The large wings of the fan were whirring industriously in the heights, the white-linen clad Chinese boys were gliding through the hall with silent composure purveying the bad English-Indian food, and the electric light was glittering on the small ice cubes floating in the whisky glasses. I sat facing my friend, tired and not hungry, sipped my cold drink, peeled golden yellow bananas, and called rather too soon for coffee and cigars.

The others had decided to go see a film, something for which my eyes, strained already from laboring in full sun, were not eager. However, in the end I went along, just to have the evening taken care of. We walked out of the hotel bareheaded and in light evening shoes and strolled through the teeming streets in the cooled-down, blue evening air. In quiet side streets, in the light of storm lanterns, hundreds of Chinese coolies sat at long, rough wooden tables and cheerily and politely ate their mysterious and complex dishes, which cost practically nothing and are full of unknown spices. The intense scent of dried fish and warm coconut oil floated through the night lit by a thousand flickering candles; calls and shouts in dark Eastern languages echoed out of blue arch-covered alleys; pretty made-up Chinese girls sat in front of lightly barred doors, behind which rich, golden house altars dimly glittered.

The intense scent of dried fish and warm coconut oil floated through the night lit by a thousand flickering candles; calls and shouts in dark Eastern languages echoed out of blue arch-covered alleys; pretty made-up Chinese girls sat in front of lightly barred doors, behind which rich, golden house altars dimly glittered.

From the dark wooden gallery in the movie house, we looked over the heads of innumerable Chinese with long queues at the glaring rectangle of light where a Parisian gambler’s tale, the theft of the Mona Lisa, and scenes from Schiller’s Kabale und Liebe flitted by like ghosts, all with the same harsh vividness, the ghost-like quality being doubled by the atmosphere of unreality or awkward implausibility that all these Western things take on in a Chinese and Malay environment.

My attention soon went slack, my gaze hung distractedly in the twilight of the high room, and my thoughts fell to pieces and lay lifeless like the limbs of a marionette that was not in use at the moment and had been laid aside. I let my head sink onto my propped-up hands and was immediately at the mercy of all the moods of my thought-weary and image-sated brain.

At first I was surrounded by a soft murmuring twilight that I felt good in and that I felt no need to think about. Then gradually I began to notice that I was lying on the deck of a ship, it was night, and only a few oil lanterns were burning. Aside from me, many other sleepers were lying there, body to body, each stretched out on the deck on his travel blanket or on a bast mat.

A man who was lying next to me seemed not to be asleep. His face was familiar to me, though I didn’t know his name. He moved, propping himself on his elbows, took rimless golden spectacles from his eyes, and began to clean them meticulously with a soft little flannel cloth. Then I recognized him—it was my father.

“Where are we going?” I asked sleepily.

He kept cleaning his delicate spectacles without looking up and quietly said, “We’re going to Asia.”

He kept cleaning his delicate spectacles without looking up and quietly said, “We’re going to Asia.”

We spoke Malay mixed with English, and this English reminded me that my childhood was long past, because back then my parents told each other all their secrets in English, and I could understand nothing of them.

“We’re going to Asia,” my father repeated, and then all of a sudden I again knew everything. Yes, we were going to Asia, and Asia was not an area of the world but rather a very specific but mysterious place somewhere between India and China. That is where the various peoples and their teachings and their religions had come from, there lay the roots of all humanity and the source of all life, there stood the images of the gods and the tables of the law. Oh, how had I been able to forget that, even for a moment! I had been on my way to that Asia for such a long time already, I and many men and women, friends and strangers.

Softly I sang our traveling song to myself: “We’re going to Asia!” And I thought of the golden dragons, the venerable Bodhi Tree, and the sacred snake.

My father looked at me in a kindly way and said, “I am not teaching you, I am just reminding you.” And in saying that, he was no longer my father, his face smiled for just a second with exactly the same expression with which our leader, the guru, smiles in dreams; and in the same moment the smile dissolved, and the face was round and still like a lotus blossom and exactly resembled a golden likeness of the Buddha, the Perfect One; and it smiled again and it was the mellow, sad smile of the Savior.

The person who had been lying next to me and had smiled was no longer there. It was daytime, and all the sleepers had gotten up. Distraught, I also pulled myself to my feet and wandered around on the weird ship among strange people, and I saw islands on the dark blue sea with wild, shining chalk cliffs and islands with tall windblown palms and deep blue volcanic mountains. Cunning, brown-skinned Arabs and Malays were standing with their thin arms crossed on their breasts. They were bowing to the ground and performing the appropriate prayers.

“I saw my father,” I shouted out loud. “My father is on the ship!”

An old English officer in a flowered Japanese morning gown looked at me with shining bright-blue eyes and said, “Your father is here and is there, and is in you and outside you, your father is everywhere.”

I gave him my hand and told him that I was traveling to Asia in order to see the sacred tree and the snake, and in order to return to the source of life from which everything began and which signified the eternal unity of appearances.

I gave him my hand and told him that I was traveling to Asia in order to see the sacred tree and the snake, and in order to return to the source of life from which everything began and which signified the eternal unity of appearances.

But a merchant eagerly took hold of me and claimed my attention. He was an English-speaking Singhalese. He pulled a small cloth bundle out of a little basket, which he untied and out of which small and large moonstones appeared.

“Nice moonstones, sir,” he whispered conspiratorially, and when I tried forcefully to pull myself away from him, someone laid a hand lightly on my arm and said, “Give me a few stones, they’re really beauties.” The voice immediately captured my heart as a mother captures her runaway child. I turned around eagerly and greeted Miss Wells from America. It was inconceivable that I had so completely forgotten her.

“Oh, Miss Wells,” I called out joyfully, “Miss Annie Wells, are you here too?”

“Won’t you give me a moonstone, German?”

I quickly reached into my pocket and pulled out the long, knit coin purse that I had gotten from my grandfather and that as a boy I had lost on my first trip to Italy. I was glad to have it back again, and I shook a bunch of silver Singhalese rupees out of it. But my traveling companion, the painter, who I hadn’t realized was still there and was standing next to me, said with a smile, “You can wear them as buttons; here they’re not worth a penny.”

Puzzled, I asked him where he had come from and if he had really gotten over his malaria. He shrugged his shoulders and said, “Modern European painters should all be sent to the tropics so they can wean themselves from their orange-ish palettes. Here is just the place where you can get much closer to the darker palette of nature.”

It was obvious, and I emphatically agreed. But the beautiful Miss Wells in the meantime had gotten lost in the crowd. Anxiously, I made my way farther around the huge ship, but did not have the courage to force myself past a group of missionary people who were sitting in a circle that blocked the entire width of the deck. They were singing a pious song and I quickly joined in, since I knew it from home:

Darunter das Herze sich naget und plaget

Und dennoch kein wahres Vergnügen erjaget

(Beneath it the heart is still fretting and striving,

No true lasting happiness ever deriving . . .)

I found myself in agreement with that, and the heavy-hearted, pathetic melody put me in a sad mood. I thought of the beautiful American woman and of our destination, Asia, and found so much cause for uncertainty and care that I asked the missionary how things really stood: Was his faith truly a good one and would it be any good for a man like me?

“Look,” I said, hungry for consolation, “I’m a writer and a butterfly collector—”

“You’re mistaken,” said the missionary.

I repeated my explanation. But whatever I said, he responded with the same answer: “You’re mistaken,” accompanied by a bright, childish, modestly triumphant smile.

Confused, I got away from him. I saw that I was not going to accomplish anything there, and I decided to drop everything and look for my father, who would certainly help me. Again I saw the face of the serious English officer and thought I heard his words: “You father is here and he is there, and he is in you and outside of you.” I understood that this was a warning, and I squatted down and began to chasten myself and to seek my father within me.

I remained still that way and tried to think. But it was hard, the whole world seemed to have been gathered on this ship in order to torment me. Also it was terribly hot, and I would gladly have given my grandfather’s knit purse for a cold whisky and soda.

From the moment I became aware of it, this satanic heat seemed to swell and grow like a horrible, unbearably piercing sound. People lost all trace of composure. They swilled greedily out of straw-covered bottles like wolves, they tried in the most bizarre ways to make themselves comfortable, and all around me the most uncontrolled, meaningless actions were occurring. The whole ship was obviously on the brink of insanity.

The friendly missionary, with whom I had been unable to come to an understanding, had fallen into the hands of two gigantic Chinese coolies who were toying with him in the most shameless ways. Through some hideous trick of authentic Chinese mechanics, they were able, with a nudge, to make him stick his booted foot into his own mouth. With another kind of nudge, they made both his eyes hang out of their sockets like sausages, and when he tried to pull them back in, they prevented him from doing so by tying knots in them.

This was grotesque and ugly but it affected me less than I would have thought, in any case less than gazing at the view afforded me by Miss Wells, for she had taken off all her clothes and wore over her amazingly buxom nakedness not a thing on her body but a marvelous, brown-green snake, which had coiled itself around her.

In despair, I closed my eyes. I had the feeling that our ship was spiraling rapidly down into a glowering, hellish maw.

Then I heard, coming as a comfort to the heart like the sound of a bell, a wanderer lost in the mist intoning with many voices a joyous song, and I immediately began to sing along. It was the sacred song, “We’re going to Asia,” and all human languages could be heard in it, all weary human longing, and the inner need and wild yearning of all creatures. I felt myself loved by my father and mother, led by my guru, purified by Buddha, and saved by the Savior, and if what came now was death or beatitude, I simply could not care which.

Then I heard, coming as a comfort to the heart like the sound of a bell, a wanderer lost in the mist intoning with many voices a joyous song, and I immediately began to sing along. It was the sacred song, “We’re going to Asia,” and all human languages could be heard in it, all weary human longing, and the inner need and wild yearning of all creatures. I felt myself loved by my father and mother, led by my guru, purified by Buddha, and saved by the Savior, and if what came now was death or beatitude, I simply could not care which.

I got up and opened my eyes. They were all there around me—my father, my friend, the Englishman, the guru, and everyone, all the human faces I had ever laid eyes on. They looked straight ahead with an awestruck, beautiful gaze, and I looked too, and before us a grove grew that was thousands of years old, and from the heaven-high twilight of the treetops came the rustling sound of eternity. Deep in the night of the holy shadow shone the golden glow of a primevally ancient temple gate.

Then we all fell on our knees, our longing was stilled, our journey was at an end. We closed our eyes, and my body toiled its way up out of its profound torpor. My forehead lay on the edge of the wooden railing, below me palely glimmered the shaved heads of the Chinese spectators; the stage was dark, and a murmuring echo of applause could be heard in the big projection room.

We got up and left. It was excruciatingly hot and there was a pervasive odor of coconut oil. But outside, the night wind off the sea, the flickering lights of the harbor, and the faint light of the stars came to greet us.

Related Books

In thinking about year-end gifts, we want to share what YOU have to say.

Below are some lovely quotations from readers on their favorite Shambhala books.

Do you have one to add? Please comment at the bottom!

“This book showed me a different way, a way to devote discipline of both my body and mind.”

—Clint

“As a therapist, I recommend this to anyone seeking permanent life change realistically.”

—Paul

“If there is one book in my collection that I could give away to everyone, it would be this book.”

—Michael

“This book changed my life as a writer, a teacher of writing, and as an individual!”

—Laurie

“This is a foundational book for anyone interested in delving deeper into the richness of martial arts philosophy.”

—Shane

“This book set me on a path of healing that has continued to the present day.”

—Miv

“This is, plain and simply, an astonishing book.”

—Michael

“Pure, melodic, poetic, this book should be one of the first ones on the list for every serious reader.”

—Pawan

“Every time I read Tao Te Ching, the book feels new again, fresh, as if only just discovered.”

—Robin

“Makes you really appreciate the ideas of strength and courage and the power of emotions and desire in overcoming any obstacle you face.”

—Eman

“There is playfulness and joy on every page of this book, with a unique tone that has a distinctive voice and is full of heart.”

—Caspericus

“You will smile, cry, and be moved by the writings of a master storyteller.”

—Bruce

“Filled with beautiful photos, delightful recipes, and creative picnic themes, each page gives inspiration to get outdoors!”

—Carly

“This one hits the sweet spot for our busy lives with wonderful recipes of vegetarian dinners!”

—Alice

“Kino will motivate you to stick to the practice and walk the yogi path.”

—Julie

“A remarkable vision and an inspiring perspective of the challenges and opportunities in the chaotic, divisive, and evolving global cultures.”

—John

“I think this is a great way for beginners to get started in mindfulness without feeling overwhelmed.”

—D.

“Brilliant. Life-changing. Psycho-active. Very enlightening.”

—Mariëlle

“Beautiful artwork that is cohesive and inspiring, high-quality construction, and an informative and well-written manual.”

—Rachel

“Beautiful blend of memoir, cookbook, and reflections on living a thoughtful, food-enhanced life.”

—Kirsten