Bodhisattva's Jewel Garland:

A Root Text of Mahāyāna Instruction from the Precious Kadam Scripture

Excerpted from Kadam: Stages of the Path, Mind Training, and Esoteric Practice, Part One

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Taye (1813–1900) was a versatile and prolific scholar and one of the most outstanding writers and teachers of his time in Tibet. He was a pivotal figure in eastern Tibet’s nonsectarian movement and made major contributions to education, politics, and medicine.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

-

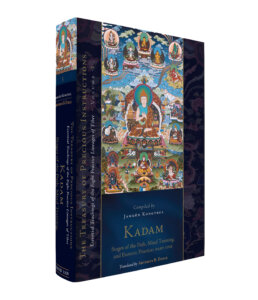

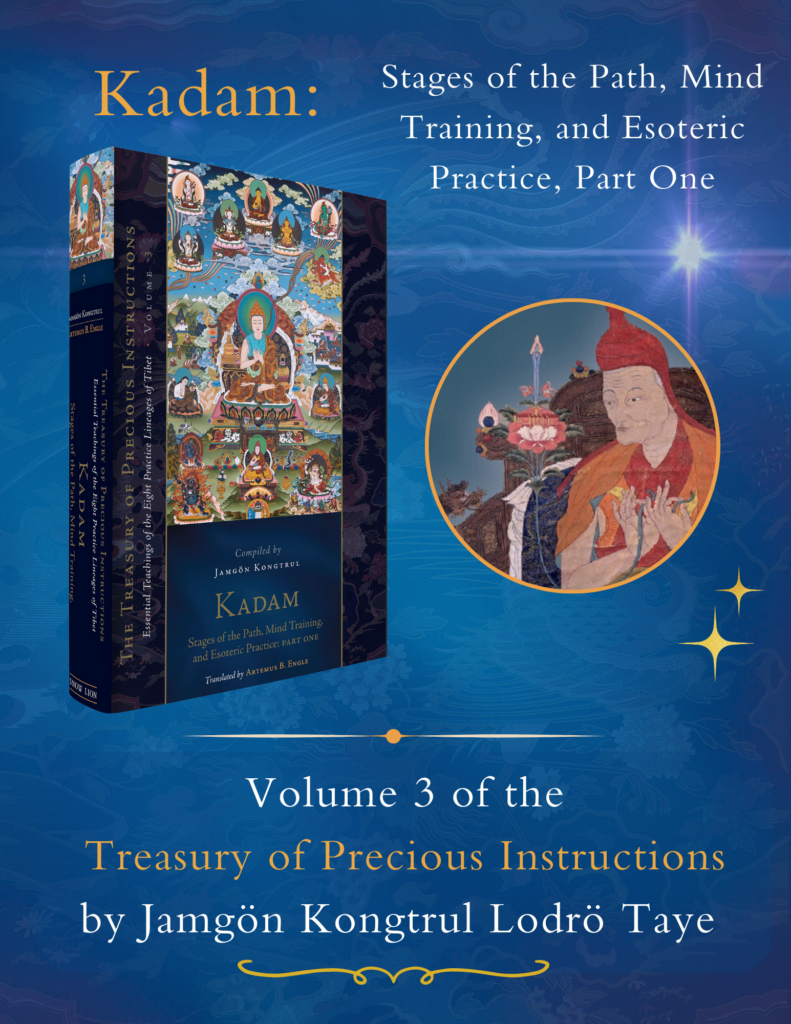

Kadam: Stages of the Path, Mind Training, and Esoteric Practice, Part One$54.95- Hardcover

Kadam: Stages of the Path, Mind Training, and Esoteric Practice, Part One$54.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Artemus B. Engle -

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part Two$49.95- Hardcover

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part Two$49.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Sarah Harding

Contributions by Taranatha

Contributions by Atisha -

Sakya: The Path with Its Result, Part Two$39.95- Hardcover

Sakya: The Path with Its Result, Part Two$39.95- HardcoverTranslated by Malcolm Smith

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye -

Marpa Kagyu, Part One$49.95- Hardcover

Marpa Kagyu, Part One$49.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Elizabeth M. Callahan -

Sakya: The Path with Its Result, Part One$44.95- Hardcover

Sakya: The Path with Its Result, Part One$44.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Malcolm Smith -

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part One$44.95- Hardcover

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part One$44.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Sarah Harding

Contributions by Taranatha

Contributions by Atisha -

Jonang: The One Hundred and Eight Teaching Manuals$39.95- Hardcover

Jonang: The One Hundred and Eight Teaching Manuals$39.95- HardcoverTranslated by Gyurme Dorje

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Contributions by Taranatha -

Zhije: The Pacification of Suffering$39.95- Hardcover

Zhije: The Pacification of Suffering$39.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Sarah Harding -

Buddha Nature$34.95- Paperback

Buddha Nature$34.95- PaperbackBy Maitreya

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

By Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso

Translated by Rosemarie Fuchs

By Asanga -

Chod: The Sacred Teachings on Severance$59.95- Hardcover

Chod: The Sacred Teachings on Severance$59.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Sarah Harding

Contributions by Rangjung Dorje

Contributions by Taranatha

Contributions by Karma Chagme

Contributions by The Fourteenth Karmapa, Thekchok Dorje

Foreword by The Seventeenth Karmapa -

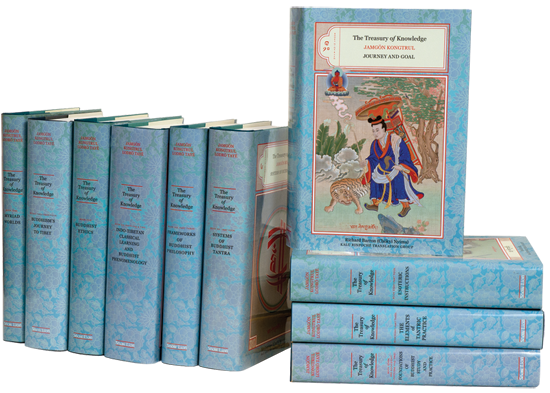

The Treasury of Knowledge

The Treasury of KnowledgeStarting at $29.95

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Kalu Rinpoche Translation Group -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Seven and Book Eight, Parts One and Two$34.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Seven and Book Eight, Parts One and Two$34.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Richard Barron (Chokyi Nyima) -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Six, Parts One and Two$49.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Six, Parts One and Two$49.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Gyurme Dorje -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Books Nine and Ten$49.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Books Nine and Ten$49.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Richard Barron (Chokyi Nyima) -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Books Two, Three, and Four$49.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Books Two, Three, and Four$49.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Ngawang Zangpo -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Eight, Part Three$44.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Eight, Part Three$44.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Ingrid Loken McLeod

Translated by Elio Guarisco -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Eight, Part Four$59.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Eight, Part Four$59.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Sarah Harding -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Six, Part Three$44.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Six, Part Three$44.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Elizabeth M. Callahan -

Chod Practice Manual and Commentary$19.95- Paperback

Chod Practice Manual and Commentary$19.95- PaperbackBy The Fourteenth Karmapa, Thekchok Dorje

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by V.V. Lama Lodo Rinpoche

Foreword by H.E. Bokar Rinpoche -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Six, Part Four$35.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Six, Part Four$35.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Ingrid Loken McLeod

Translated by Elio Guarisco -

The Great Path of Awakening$16.95- Paperback

The Great Path of Awakening$16.95- PaperbackBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Ken McLeod -

Timeless Rapture$29.95- Hardcover

Timeless Rapture$29.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Edited by Ngawang Zangpo

Translated by Ngawang Zangpo -

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book One$29.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book One$29.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Kalu Rinpoche Translation Group -

The Treasury of Knowledge, Book Five$49.95- Hardcover

The Treasury of Knowledge, Book Five$49.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Kalu Rinpoche Translation Group -

The Torch of Certainty$22.95- Paperback

The Torch of Certainty$22.95- PaperbackBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Foreword by Chogyam Trungpa

Translated by Judith Hanson -

The Teacher-Student Relationship$24.95- Paperback

The Teacher-Student Relationship$24.95- PaperbackBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Foreword by Lama Tharchin

Translated by Ron Garry -

Jamgon Kongtrul's Retreat Manual$34.95- Paperback

Jamgon Kongtrul's Retreat Manual$34.95- PaperbackBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Ngawang Zangpo

- Buddhism and Science 2item

- Drukpa Kagyu Tradition 3item

- Treasury of Precious Instructions 9item

- Buddhist Academic 7item

- Buddhist Anthology 1 item

- Buddhist Art 2item

- Buddhist Astrology 3item

- Buddhist Biography/Memoir 4item

- Buddhist Ethics 2item

- Buddhist History 9item

- Buddhist Overviews 16item

- Buddhist Philosophy 10item

- Buddhist Yoga 3item

- Dependent Origination 3item

- Healing in Buddhism 2item

- Women in Buddhism 1 item

- Abhidharma 2item

- Buddha Nature 1 item

- Chod 5item

- Deity Practice 3item

- Five Maitreya Texts 1 item

- Gelug Tradition 3item

- Guru Yoga 1 item

- Jonang Tradition 7item

- Kadam Tradition 7item

- Drukpa Kagyu 2item

- Kagyu Tradition 15item

- Karma Kagyu 1 item

- Shangpa Kagyu 7item

- Kalachakra 3item

- Karmapas 1 item

- Lojong/Mind Training 1 item

- Madhyamaka 3item

- Mahamudra 4item

- Ngondro 1 item

- Nyingma Tradition 10item

- Phowa 5item

- Sakya Tradition 9item

- Tantra 8item

- Terma / Treasure Texts 1 item

- Tibetan Medicine 2item

- Tulku Tradition 2item

- Yogacara 2item

- Buddhist Poetry 2item

- Biography 1 item

GUIDES

Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland: An Excerpt from Kadam, Part One

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Artemus B. Engle

About Kadam

The third volume of this series covers the teachings and practices of the Kadam lineage. This tradition is based on the teachings of the Indian master Atiśa, who traveled to Tibet in the early eleventh century and stayed for twelve years transmitting teachings that would be embraced by many traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. The three categories of teachings covered here and in the fourth volume of the series—Stages of the Path, Mind Training, and Esoteric Instructions—correspond to three root texts: Atiśa’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, the aphorisms of the Seven-Point Mind Training, and Atiśa’s Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland. This volume also contains ritual texts on the bodhisattva vow conferral, as well as commentaries by Tsongkhapa, Tāranātha, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, and Jamgön Kongtrul, himself. The fourth volume of The Treasury of Precious Instructions series extends these commentaries and includes material on the esoteric instructions known as the Sixteen Drops.

About The Treasury of Precious Instructions

The Treasury of Precious Instructions by Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Taye, one of Tibet’s greatest Buddhist masters, is a shining jewel of Tibetan literature, presenting essential teachings from the entire spectrum of practice lineages that existed in Tibet. In its eighteen volumes, Kongtrul brings together some of the most important texts on key topics of Buddhist thought and practice as well as authoring significant new sections of his own.

Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland

Chapter 3, page 19-23

By Atiśa

Translated by Thupten Jinpa

Sanskrit title: Bodhisattvamaṇevalī

Homage to great compassion.

Homage to the teachers.

Homage to the faith divinities.

Discard all lingering doubts,

and strive with dedication in your practice.

Thoroughly relinquish sloth, mental dullness, and laziness,

and strive always with joyful perseverance. (1)

With mindfulness, vigilance, and conscientiousness,

constantly guard the gateways of your senses.

Again and again, three times both day and night,

examine the flow of your thoughts. (2)

Reveal your own shortcomings,

but do not seek out others’ errors.

Conceal your own good qualities,

but proclaim those of others. (3)

Forsake wealth and ministrations;

at all times relinquish gain and fame.

Have modest desires, be easily satisfied,

and reciprocate kindness. (4)

Cultivate love and compassion,

and stabilize your awakening mind.

Relinquish the ten negative actions,

and always reinforce your faith. (5)

Destroy anger and conceit,

and be endowed with humility.

Relinquish wrong livelihood,

and be sustained by ethical livelihood. (6)

Forsake material possessions,

embellish yourself with the wealth of the noble ones.

Avoid all trifling distractions,

and reside in the solitude of wilderness. (7)

Abandon frivolous words;

constantly guard your speech.

When you see your teachers and preceptors,

reverently generate the wish to serve. (8)

Wise beings with dharma eyes

and beginners on the path as well—

recognize them as your spiritual teachers.

In fact when you see any sentient being,

view them as your parent, your child, or your grandchild. (9)

Renounce negative friendships,

and rely on a spiritual friend.

Dispel hostility and unpleasantness,

and venture forth to where happiness lies. (10)

Abandon attachment to all things

and abide free of desire.

Attachment fails to bring even the higher realms;

in fact, it kills the life of true liberation. (11)

When you encounter the causes of happiness,

in these always persevere.

Whichever task you take up first,

address this task primarily.

In this way, you ensure the success of both tasks,

where otherwise you accomplish neither. (12)

Since you take no pleasure in negative deeds,

when a thought of self-importance arises,

at that instant deflate your pride

and recall your teacher’s instructions. (13)

When discouraged thoughts arise,

uplift your mind

and meditate on the emptiness of both.

When objects of attraction or aversion appear,

view them as you would illusions and apparitions. (14)

When you hear unpleasant words,

view them as mere echoes.

When injuries afflict your body,

see them as the fruits of past deeds. (15)

Dwell utterly in solitude, beyond town limits.

Like the carcass of a wild animal,

hide yourself away in the forest

and live free of attachment. (16)

Always remain firm in your commitment.

When a hint of procrastination and laziness arises,

at that instant enumerate your flaws

and recall the essence of spiritual conduct. (17)

However, if you do encounter others,

speak peacefully and truthfully.

Do not grimace or frown,

but always maintain a smile. (18)

In general, when you see others,

be free of miserliness and delight in giving;

relinquish all thoughts of envy. (19)

To help soothe others’ minds,

forsake all disputation

and be endowed with forbearance. (20)

Be free of flattery and fickleness in friendship;

be steadfast and reliable at all times.

Do not disparage others,

but always abide with a respectful demeanor. (21)

When giving advice,

maintain compassion and altruism.

Never defame the teachings.

Whatever practices you admire,

with aspiration and the ten spiritual deeds,

strive diligently, dividing day and night. (22)

Whatever virtues you gather through the three times,

dedicate them toward the unexcelled great awakening.

Disperse your merit to all sentient beings,

and utter the peerless aspiration prayers

of the seven limbs at all times. (23)

If you proceed thus, you’ll swiftly perfect merit and wisdom

and eliminate the two defilements.

Since your human existence will be meaningful,

you’ll attain the unexcelled enlightenment. (24)

The wealth of faith, the wealth of morality,

the wealth of giving, the wealth of learning,

the wealth of conscience, the wealth of shame,

and the wealth of insight—these are the seven riches. (25)

These precious and excellent jewels

are the seven inexhaustible riches.

Do not speak of these to those not human.

Among others guard your speech;

when alone guard your mind. (26)

This concludes the Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland composed by the Indian abbot Dīpaṃkara Śrījñāna.

Books Related to Kadam

Tibetan Buddhist Books in 2023: A Review

See our other Year in Review Guides:

Zen and Chan | Tibetan Buddhism | More in Buddhism

Yoga | Kids Books

Buy 2 books for 20% off, 3 books for 30% off, 4 or more for 35% off.

Applies to physical copies only, Discount applies automatically

We are very happy to share with you a look back at our 2023 books for those who practice in the Tibetan tradition.

Jump to: Reader Guides | Books | Books for Kids | Audiobooks | Forthcoming Books

Remebering Tulku Thondup Rinpoche

The Passing of Christina Monson

Tibetan Masters of the 10th-11th Centuries

Tibetan Masters of the 8th Century

Indian Mahayana Masters of the 2nd-8th Centuries

Naropa: A Reader’s Guide to the Great Master of Mahamudra

Tilopa: A Guide for Readers to the Indian Mahasiddha

Rongzom Mahapandita: A Guide for Readers to Rongzompa

The Guhyagarbha Tantra: A Reader’s Guide to the Glorious Secret Essence

Tangtong Gyalpo: A Guide for Readers

Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso: A Guide for Readers

Buddhist Mindfulness: A Guide for Readers

The Works of B. Alan Wallace: A Guide for Readers

Tara the Liberator: A Guide for Readers

A Reader’s Guide to Madhyamaka

Doha and Gur: Indian and Tibetan Songs of Realization

Gyatrul Rinpoche: A Guide for Readers

Paperback | Ebook | Audiobook

$21.95 - Paperback

Awakening Wisdom: Heart Advice on the Fundamental Practices of Vajrayana Buddhism

By Pema Wangyal Rinpoche, translated by Padmakara Translation Group

If you are new to Tibetan Buddhism, this short work will help you get started with your practice; and if you are well steeped in these teachings, it will inspire and motivate you to practice them.

While accessible for beginners, this short volume conveys incredible profundity as well. Originally delivered in the form of advice to retreatants, Pema Wangyal’s teachings cover the practices found across various lineages' foundational practices. But there is a lot more here including the focus on motivation which carries through all the practices; the specifics of posture and somatic breathing; visualization and mantra; mantra of the Budhhas, the mantra of the Prajnaparamita; the practice of Tonglen, and more.

In the last part of the book, he provides guidance about the preliminary practices using as a model those from the Dudjom lineage but applicable for everyone. Pema Wangyal’s writing is suffused with warmth and tenderness throughout, making this book quite accessible and inviting to everyone.

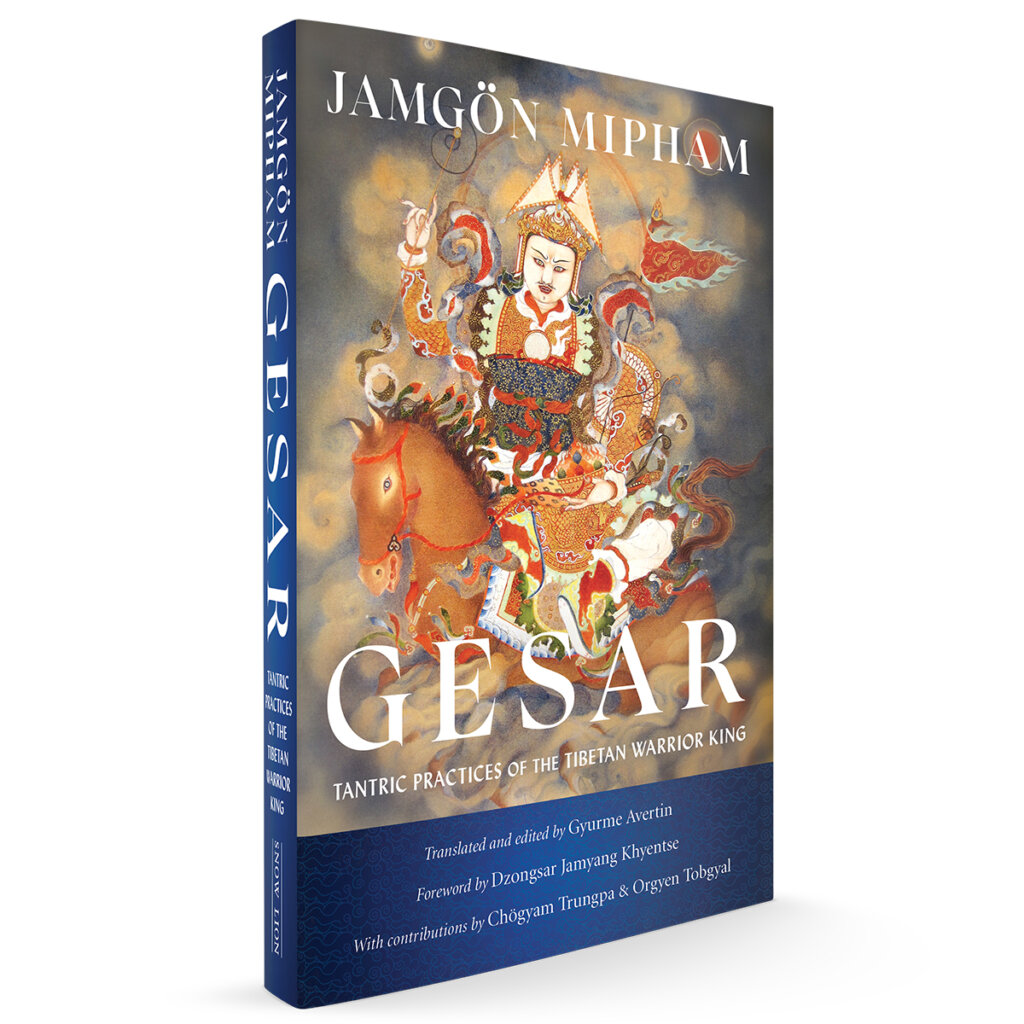

Paperback | Ebook

$29.95 - Paperback

Gesar: Tantric Practices of the Tibetan Warrior King

By Jamgon Mipham

Foreword by Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse

Edited and translated by Gyurme Avertin

Contributions by Chogyam Trungpa and Orgyen Tobgyal

Gesar of Ling is well known in Tibetan history, literature, and folklore but for Buddhist practitioners he is an enlightened tantric protector and deity, an emanation of Padmasambhava. Engaging in Gesar practice is meant to generate positive circumstances and increase one’s experiences and realization in Buddhist practice.

Three outstanding figures introduce and present this selection of 52 prayers and practices devoted to Gesar compiled by Ju Mipham Rinpoche (1846–1912).

Dzongsar Khyentse cuts through the web of cultural accretions which westerns tend to get caught up in and shows how “Mipham Rinpoche, who had himself invoked the spirit of profound brilliance, recognized that everything about Gesar of Ling had the potential to inspire authentic presence and an appreciation of nowness. And he didn’t think twice about making use of any of it.”

In Chogyam Trungpa’s essay, “Gesar the Warrior” he demonstrates the how Gesar practice embodies the Buddhist notion of warriorship: “Becoming a warrior means that we can look directly at ourselves, see the nature of our cowardly mind, and step out of it. We can trade our small-minded struggle for security for a much vaster vision, one of fearlessness, openness, and genuine heroism”.

And Orgyen Tobgyal, over the course of a disarmingly frank 30 page elucidation of Gesar practice, leaves the reader with a very clear understanding how to approach these practices and understand Gesar.

The forty-five page introduction by the translator gives an overview of all aspects of Gesar and the corpus of texts included in this book.

These practices are meant to be practiced under the guidance of an authentic spiritual teacher. They detail poetic imagery and include guru yoga, praises, invocations, and divinations. Central to all of these practices is raising what is known in Tibetan as lungta, or “windhorse,” a dignified energy that propels and enhances one’s wisdom, compassion, and power to benefit all beings.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

By Andy Karr, foreword by Matthieu Ricard

Into the Mirror is a call to cultivate wisdom and compassion—right within this world of illusion—and an insightful challenge to the rampant materialism of modernity. Andy Karr presents accessible and powerful methods to accomplish this through investigating the way our minds construct our worlds.

Combining contemporary Western inquiries with classical Buddhist investigations into the nature of mind, Karr invites the reader to make a personal, experiential journey through study, contemplation, and meditation. He presents a series of contemplative practices from Mahayana Buddhism, starting with the Middle Way teachings on emptiness and interdependence, through Yogachara’s subtle understanding of nonduality, to the view that buddha nature is already within us to be revealed rather than something external to be acquired.

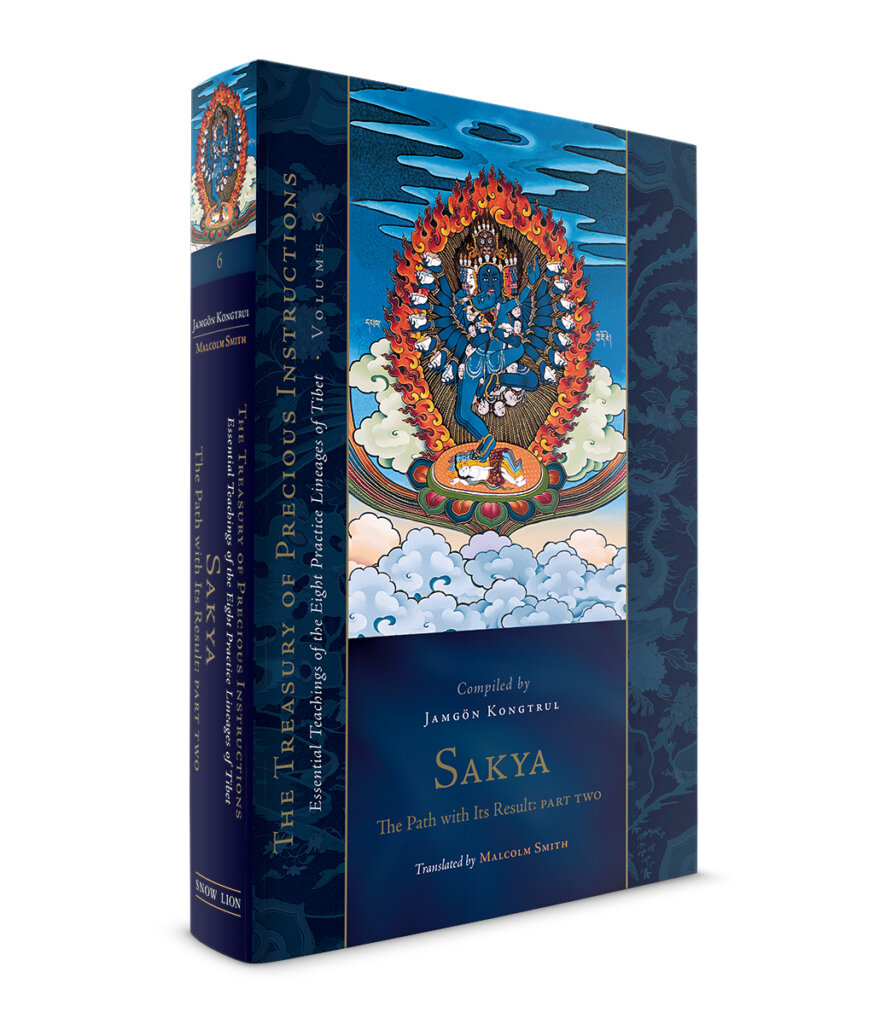

Hardcover | Ebook

$39.95 - Hardcover

Sakya: The Path with Its Result, Part Twp: Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 6

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Malcolm Smith

The sixth volume of this series, and part two of Sakya: The Path with Its Result, completes Kongtrul’s presentation of a selection of texts from the Sakya tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. This volume includes the complete teachings and practices of the Eight Ancillary Path Cycles. These eight complete the nine path cycles that begin with Virūpa’s Vajra Verses found in volume five of the series. These path cycles are generally only taught to students who have received the entire Path with Its Result (Lamdre) teaching. They contain oral instructions transmitted to Drokmi Lotsāwa by the early eleventh-century Indian masters—Ācārya Vīravajra, Mahāsiddha Amoghavajra, Pandita Prajñāgupta of Oddiyāna, and Pandita Gayadhara. These cycles provide copious material on the creation and completion stages, which was incorporated later into the Three Tantras literature, the signature Vajrayāna teaching of the Sakya school.

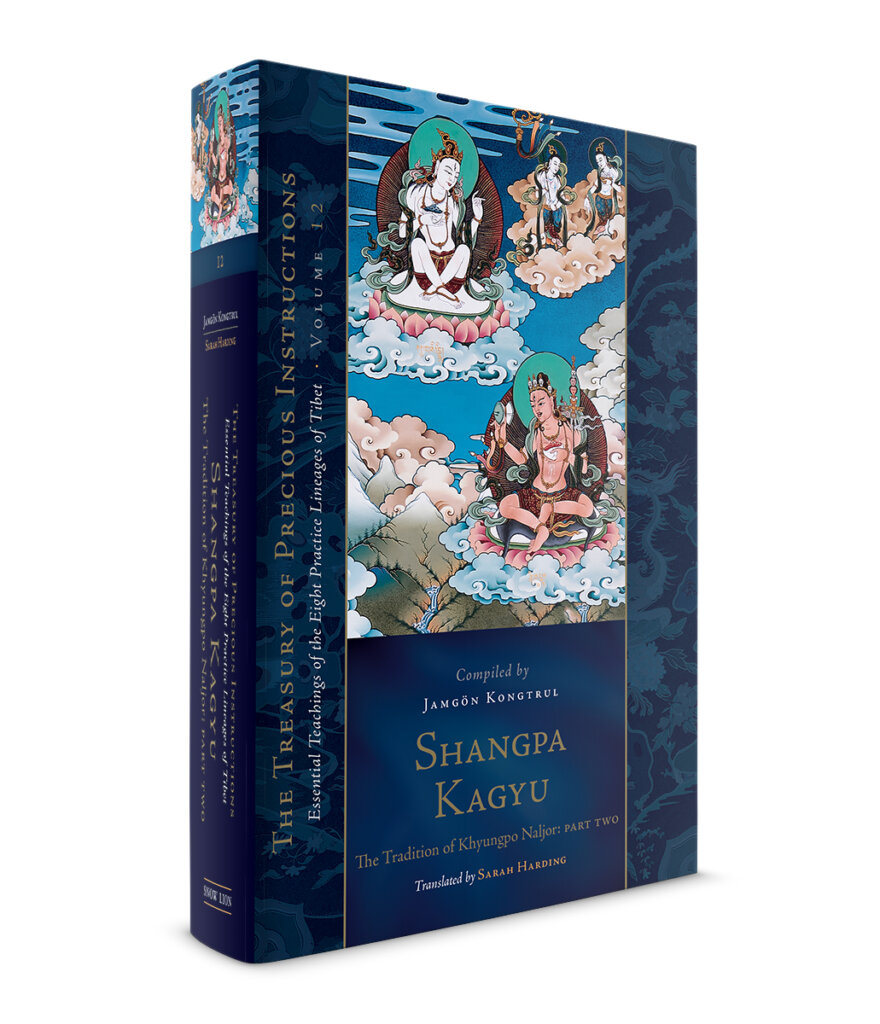

Hardcover | Ebook

$49.95 - Hardcover

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part Two: Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 12

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Sarah Harding

This is the second of two volumes that present teachings and practices from the Shangpa Kagyu practice lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. This tradition derives from two Indian yoginīs, the dākinīs Niguma and Sukhasiddhi, and their disciple, the eleventh-century Tibetan yogi Khyungpo Naljor Tsultrim Gönpo of the Shang region of Tibet. There are forty texts in this volume, beginning with Jonang Tāranātha’s classic commentary and its supplement expounding the Six Dharmas of Niguma. It includes the definitive collection of the tantric bases of the Shangpa Kagyu—the five principal deities of the new translation (sarma) traditions and the Five-Deity Cakrasamvara practice. The source scriptures, liturgies, supplications, empowerment texts, instructions, and practice manuals were composed by Tangtong Gyalpo, Tāranātha, Jamgön Kongtrul, and others.

Hardcover | Ebook

$49.95 - Hardcover

Marpa Kagyu, Part One: Methods of Liberation: Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 7

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Elizabeth Callahan

Mahāsiddha Practice, the sixteenth volume, presents a selection of teachings and practices centered on the mahāsiddhas, Indian tantric masters. The mahāsiddha Mitrayogin, whose work forms the majority of this volume, visited Tibet in the late twelfth century. His ritual texts along with instructions are here translated from Tibetan, including sādhanas, empowerments, guru yogas, authorization rituals for protector deities, and detailed compositions on Mahāmudrā practice, or resting in the nature of mind. In addition to instructions given by mahāsiddhas, this volume includes ritual practices to visualize them and transmit their blessings, beginning with a devotional text composed by Jamgön Kongtrul himself.

Paperback | Ebook

$22.95 - Paperback

Embodying Tara: Twenty-One Manifestations to Awaken Your Innate Wisdom

By Chandra Easton

Tara, the Buddhist goddess of compassion, can manifest within all of us. In this illustrated introduction to Tara's twenty-one forms, respected female Buddhist teacher and practitioner Dorje Lopön Chandra Easton shows you how to invite Tara’s awakened energy to come alive in yourself through:

- insight into core Buddhist concepts and teachings;

- meditations;

- mantra recitations; and

- journal exercises.

The relatable stories from Buddhist history and the author’s personal reflections will give you the tools to live a more compassionate life, befriend your fears, and overcome everyday challenges.

Find out how important women and movements in modern history have achieved this through their own embodiment of Tara's enlightened activities. The stories of Jane Goodall, Nawal El Saadawi, Oprah Winfrey, Vandana Shiva, Black Lives Matter, Me Too, and others will inspire you to bring these aspects of Tara into the world in creative and socially conscious ways for the benefit of all.

Rebirths: New Editions of Classics

Paperback | Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

Wisdom Nectar: Dudjom Rinpoche's Heart Advice

By Dudjom Rinpoche, foreword by Lama Tharchin Rinpoche

Dudjom Rinpoché was one of the most important figures in Tibetan Buddhism in the twentieth century, yet very few of his religious writings have been translated into English. This volume contains a generous selection of his monumental teachings and writings, the core of which is a lengthy discussion of the entire path of Dzogchen, including key instructions on view, meditation, and conduct, along with direct advice on how to bring one’s experiences onto the path.

Also included in this book in their entirety are the oral instructions, tantric songs, and songs of realization from His Holiness’s Collected Works, along with selections from his aspiration and supplication prayers.

Paperback | Ebook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Autobiography of Jamgon Kongtrul: A Gem of Many Colors

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Richard Barron (Chokyi Nyima)

This extraordinary account of the life of Tibet’s Leonardo da Vinci provides, in his own words, an illuminating glimpse into the religion, culture, and politics of nineteenth-century Tibet.

Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Thayé (1813–1899) was one of the most influential figures and prolific writers in the Tibetan Buddhist world. He was a founder and the single most important proponent of the nonsectarian Rimé movement that flourished in eastern Tibet and remains popular today.

This volume includes the first English translation of Kongtrul’s autobiography, A Gem of Many Colors, and two additional texts. The first, written by one of Kongtrul’s close personal students, discusses Kongtrul’s final days, his funeral, and the commemorative rites following his death. The second, authored by Kongtrul himself, recounts his past lives. Taken together, these three texts place Kongtrul firmly in his historical context as one of the most important Buddhist masters to ever hail from Tibet.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

Reflections on a Mountain Lake: Teachings on Practical Buddhism

By Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo

An inspiring, practical guide to walking the spiritual path with wisdom and ease—from one of the foremost living Buddhist nuns.

This broad-ranging collection of Dharma teachings by Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo addresses topics of common concern to Buddhist practitioners from all traditions—including the particular challenges facing Western practitioners, what to expect of a teacher-student relationship, gender issues and the role of women, how to approach meditation practice, and much more. Personable, witty, and profound, Tenzin Palmo presents an inspiring and no-nonsense view of Buddhist practice that comes from a heart infused with wisdom and compassion.

New in Paperback

Hardcover | Ebook | Audiobook

$21.95 - Paperback

How We Live Is How We Die

By Pema Chodron

In How We Live Is How We Die, Pema Chödrön shares her wisdom for working with this flow of life—learning to live with ease, joy, and compassion through uncertainty, embracing new beginnings, and ultimately preparing for death with curiosity and openness rather than fear.

Poignant for readers of all ages, her teachings on the bardos—a Tibetan term referring to a state of transition, including what happens between this life and the next—reveal their power and relevance at each moment of our lives. She also offers practical methods for transforming life’s most challenging emotions about change and uncertainty into a path of awakening and love. As she teaches, the more freedom we can find in our hearts and minds as we live this life, the more fearlessly we’ll be able to confront death and what lies beyond. In all, Pema provides readers with a master course in living life fully and compassionately in the shadow of death and change.

Hardcover | Ebook

$21.95 - Hardcover

The Magical Life of the Lotus-Born

By Sherab Kohn

Explore a fresh telling of the inspiring, mysterious, and magical life of the great master Padmasambhava—the Lotus-Born—who planted the seed of Buddhism in Tibet that is still blossoming today, beautifully illustrated for ages 10+.

The Lotus-Born is one of the most iconic and important figures in Tibetan history. Here, his magical life story is outlined in colorful and captivating detail, offering young readers a rare glimpse into his fierce adventures and battles that transformed Tibet, a land of malevolent spirits and wild folk, into a fertile ground for Buddhism. The rich and vibrant spiritual tradition that resulted in Tibet has thrived for over one thousand years. This timeless tale is sure to capture the imagination of future generations, just as the oral, theatrical, and written accounts of it have in the Himalayas for centuries.

Forthcoming in 2024

And we have even more from the Tibetan tradition coming out next year from the likes of Sera Khandro, Khenpo Sodargye, Khangsar Tenpe Wangchuk, Jamgon Kongtrul, Khenpo Sherab Sangpo, Gaylon Ferguson, Jigme Wangdrak, Orgyen Chowang, Thubten Chodron, Dza Kilung, Cortland Dahl, Dzigar Kongtul, Tina Draszczyk, and more. So make sure you sign up for our emails so you do not miss them! Here is a sneak peek at our first 2024 release which you can pre-order now and take advantage of the discount.

Tibetan Buddhism: A Guide to Contemplation, Meditation, and Transforming Your Mind

By Khenpo Sodargye

Your genuine, go-to overview of Tibetan Buddhism from a leading contemporary teacher who has traversed the wisdom path.

This guide shares Tibetan Buddhist insight and tools that will benefit everyone in transforming their mind. Khenpo Sodargye, who has attracted hundreds of thousands of students worldwide with his concise, easy-to-follow teaching style, sketches the big picture of the Mahayana path in straightforward language with stories relevant to everyday life. He draws on authentic texts and teachings by renowned Buddhist masters to explain complex concepts like:

- The Four Dharma Seals

- Faith

- Bodhicitta

- The Three Supreme Methods

- The Two Truths

- Rebirth and karma

- Spiritual teachers

- The Great Perfection

This book introduces a systematic approach to studying Buddhism. Through proper listening, contemplating, and meditating, we can generate the wisdom that enables us to recognize, control, and uproot our afflictions, which is the essence of Buddhism. This book is the perfect companion for anyone wanting to learn more about the basics of Mahayana Buddhism or to strengthen the foundations of their spiritual practice.

Marpa: A Guide for Readers

The following is the beginning of a several page profile of Marpa from Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism:

Marpa, the Tibetan founder of the Kagyu¨ lineage, represents yet another type of person. Born in 1012 of relatively prosperous parents in southern Tibet, as a young boy Marpa is depicted as possessing a fearsome temper and a violent and stubborn disposition. He is what one might call a holy terror, and while he is still young his parents send him off to be trained in the dharma with a variety of teachers. Marpa soon realizes that one has to make a lot of offerings in order to receive even basic teachings, let alone more advanced ones. Moreover, Tibetan teachers often guard their transmissions jealously, and Marpa is repeatedly rebuffed when he seeks the higher initiations.

Eventually, he comes to the conclusion that to receive the full measure of dharma instruction, he will have to journey to India. His parents capitulate, and Marpa sets off over the Himalayas on a long, tedious, and dangerous journey to India, the first of three trips he will make to the holy land. While staying in Nepal before descending to the Indian plains, Marpa hears of the siddha Naropa. His biography states, ‘‘A connection from a former life was reawakened in Marpa and he felt immeasurable yearning.’’

While many of his Tibetan contemporaries arrived in India and went straight to one or another of the great Indian monasteries for tantric instruction, Marpa takes a different course, bypassing the monastic scene, seeking for his yogin teacher in the forest. Marpa eventually finds Naropa, is accepted as a disciple, and receives extensive instruction and initiation from him.

From the first Marpa Kagyu volume of the Treasury of Precious Instructions:

Marpa Chökyi Lodrö of Lhodrak traveled to India three or four times. He received the sūtras and tantras in their entirety from many scholar-siddhas, Nāropa and Maitrīpa being the foremost among them. In particular, if his earlier and later journeys are added together, he studied with Nāropa for sixteen years and seven months. Through the combination of his listening, reflection, and meditation, Marpa came to dwell in a state of attainment. During his last journey, Nāropa had departed for [the practice of yogic] conduct. Nevertheless, enduring great hardships, Marpa searched for and supplicated Nāropa, finally actually meeting him in Puṣpahari in the North. He spent seven months with Nāropa and received the complete Aural Transmission of Cakrasaṃvara, male and female consorts. In Tibet, the principal disciples upon whom Marpa bestowed his profound dharma were known as the four great pillars. Among them, Mai Tsönpo, Ngok Chödor, and Tsurtön received the entrusted transmission of the explanatory tradition, and Jetsun Milarepa received the entrusted transmission of the practice tradition.

Paperback | Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

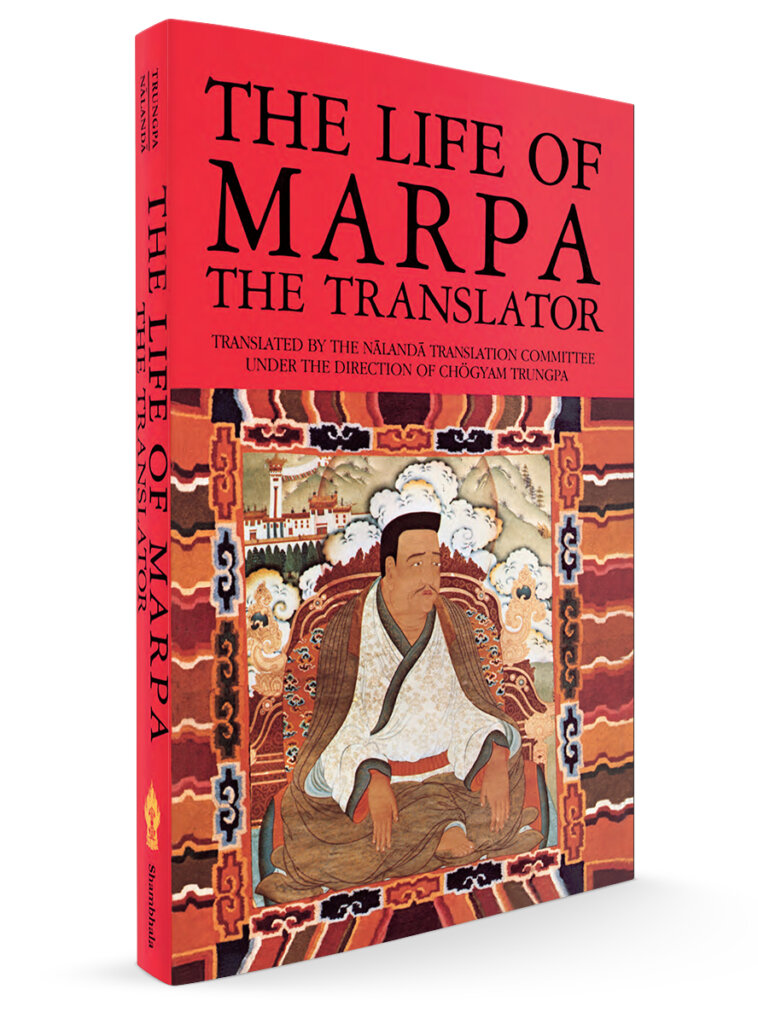

The Life of Marpa the Translator: Seeing Accomplishes All

By Tsangnyon Heruka, translated by Chogyam Trungpa amd the Nalanda Translation Committee

Marpa the Translator, the eleventh-century farmer, scholar, and teacher, is one of the most renowned saints in Tibetan Buddhist history. In the West, Marpa is best known through his teacher, the Indian yogin Naropa, and through his closest disciple, Milarepa. This lucid and moving translation of a text composed by the author of The Life of Milarepa and The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa documents the fascinating life of Marpa, who, unlike many other Tibetan masters, was a layman, a skillful businessman who raised a family while training his disciples.

As a youth, Marpa was inspired to travel to India to study the Buddhist teachings, for at that time in Tibet, Buddhism has waned considerably through ruthless suppression by an evil king. The author paints a vivid picture of Marpa's three journeys to India: precarious mountain passes, desolate plains teeming with bandits, greedy customs-tax collectors. Marpa endured many hardships, but nothing to compare with the trials that ensued with his guru Naropa and other teachers. Yet Marpa succeeded in mastering the tantric teachings, translating and bringing them to Tibet, and establishing the Practice Lineage of the Kagyus, which continues to this day.

Essential Texts by and about Marpa

Hardcover | Ebook

$49.95 - Hardcover

Marpa Kagyu, Part One - Methods of Liberation: Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 7

The Treasury of Precious Instructions

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye

The seventh volume of the series, Marpa Kagyu, is the first of four volumes that present a selection of core instructions from the Marpa Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. This lineage is named for the eleventh-century Tibetan Marpa Chokyi Lodrö of Lhodrak who traveled to India to study the sutras and tantras with many scholar-siddhas, the foremost being Naropa and Maitripa. The first part of this volume contains source texts on mahamudra and the six dharmas by such famous masters as Saraha and Tilopa. The second part begins with a collection of sadhanas and abhisekas related to the Root Cakrasamvara Aural Transmissions, which are the means for maturing, or empowering, students. It is followed by the liberating instructions, first from the Rechung Aural Transmission. This section on instructions continues in the following three Marpa Kagyu volumes. Also included are lineage charts and detailed notes by translator Elizabeth M. Callahan.

The pieces by Marpa in this volume include:

- Vajra Song on the Meaning of the Four Points: Instructions on the Ultimate Essence, the Mahāmudrā of Nonattention Heard by the Lord Marpa Lotsāwa from the Glorious Saraha

- Trulkhors for the Path of Method and the Caṇḍālī of the Saṃvara Aural Transmission

- Eighteen Trulkhors for Caṇḍālī

Paperback | Ebook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Rain of Wisdom: The Essence of the Ocean of True Meaning

Translated by Nalanda Translation Committee under the guidance of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

The art of composing spontaneous songs that express spiritual understanding has existed in Tibet for centuries. Over a hundred of these profound songs are found in this collection of the works of the great teachers of the Kagyü lineage, known as the Practice Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism.

The chapter on Marpa, entitled The Grand Songs of Marpa, is 35 pages long and includes Marpa's first departure from India, his dream of Saraha, his third trip to India, his final farewell to Naropa, his third return to Tibet, and the many songs these incidents inspired.

Paperback | Ebook

$27.95 - Paperback

The Great Kagyu Masters: The Golden Lineage Treasury

Compiled by Dorje Dze Öd, translated by Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche

The Golden Lineage Treasury was compiled by Dorje Dze Öd a great master of the Drikung lineage active in the Mount Kailasjh region of Western Tibet. This text of the Kagyu tradition profiles and the forefathers of the tradition including Vajradhara, the Buddha, Tilopa, Naropa, the Four Great Dharma Kings of Tibet, Marpa, Milarepa, Atisha, Gampopa, Phagmodrupa, Jigten Sumgon, and more.

The profile Marpa is 25 pages long.

Hardcover | Ebook

$24.95 - Hardcover

The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra: Teachings, Poems, and Songs of the Drukpa Kagyu Lineage

Translated by Gerardo Abboud, Sean Price, and Adam Kane

The Drukpa Kagyu lineage is renowned among the traditions of Vajrayana Buddhism for producing some of the greatest yogis from across the Himalayas. After spending many years in mountain retreats, these meditation masters displayed miraculous signs of spiritual accomplishment that have inspired generations of Buddhist practitioners. The teachings found here are sources of inspiration for any student wishing to genuinely connect with this tradition.

These translations include Mahamudra advice and songs of realization from major Tibetan Buddhist figures such as Gampopa, Tsangpa Gyare, Drukpa Kunleg, and Pema Karpo, as well as modern Drukpa masters such as Togden Shakya Shri and Adeu Rinpoche. This collection of direct pith instructions and meditation advice also includes an overview of the tradition by Tsoknyi Rinpoche.

This includes a chapter on Marpa's A Vision of Saraha The Essential Importance of the Uncreated Meaning of the Four Syllables of Mahamudra: A Pith Instruction Expressed in a Vajra Song. The pith instruction, the essence of the uncreated found in the meaning of the four syllables of Mahamudra, was revealed to Lord Marpa by the song of Saraha.

Combined with guidance from a qualified teacher, these teachings offer techniques for resting in the naturally pure and luminous state of our minds. As these masters make clear, through stabilizing the meditative experiences of bliss, clarity, and nonthought, we will be liberated from suffering in this very life and will therefore be able to benefit countless beings.

Translator on Gerardo Abboud on The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra

Additional Resources on Marpa

Lotsawa House hosts at least eight works by Marpa as well as several where he features.

Asanga and Yogacara: A Guide for Readers

Asanga

Asanga and Yogacara: A Guide for Readers

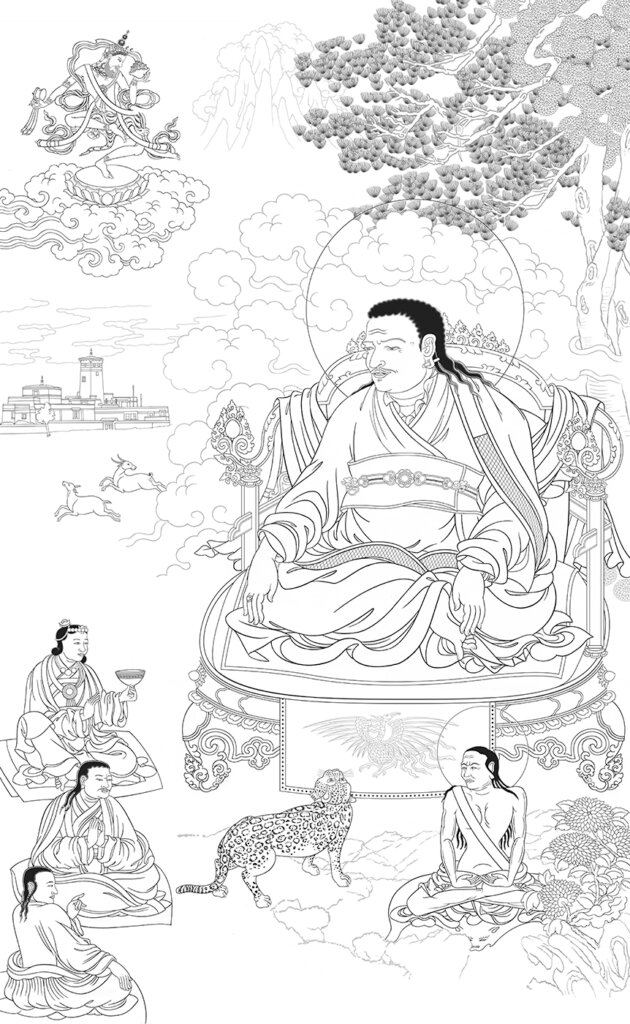

Asanga, from The Buddhist Art Coloring Book

Asanga, along with his brother Vasabandu, is an inestimably important figure in Mahayana Buddhism, associated with some of the most important works on ethical and moral dimensions of progress on the path, as well as the Yogacara philosophical school. He is particularly revered in Tibet and East Asia.

Asanga is best known for his two "Summary Treatises" and the teachings he received from Maitreya, the Five Maitreya texts.

The following is from Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism:

Asanga, considered the founder of the Yogachara school, was born into a Buddhist family in the region of Gandhara in northwestern India.3 As a child, he was drawn strongly to meditation but was also schooled in the major divisions of learning then current in India, including writing, debate, mathematics, medicine, and the fine arts. Asanga was a brilliant student and excelled at whatever he tried. At an early age, he took Buddhist ordination within a Hinayana sect, the Mahishasaka, known for the great importance it attached to the practice of meditation.

Asanga trained under several teachers, mastering the Hinayana scriptures and studying Mahayana sutras. When he encountered the Prajnaparamita sutras, however, he found that while he could read their words, he did not really understand their inner meaning or the awakening they described. Asanga felt compelled by these teachings and recognized that the only way he could gain the transcendent wisdom that he longed for would be to enter into a meditation retreat. Having received instruction from his guru, he now went into strict retreat on Mount Kukkutapada. He spent his time meditating and supplicating his personal deity, the future buddha, Maitreya, for guidance, inspiration, and teaching.

Essential Texts by Asanga

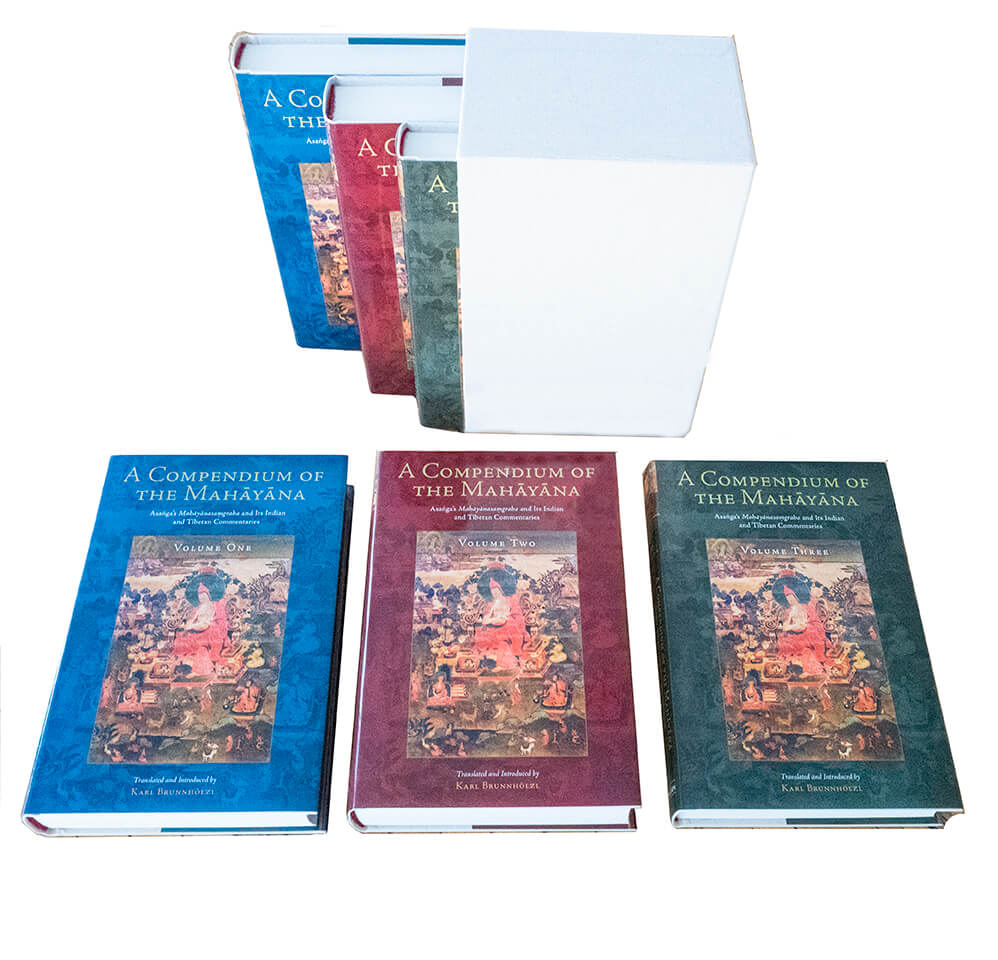

Three Volume Slipcase | Ebook

$150.00 - Hardcover

A Compendium of the Mahayana: Asanga’s Mahayanasamgraha and Its Indian and Tibetan Commentaries

By Karl Brunnholzl

Asanga's The Compendium of the Mahayana, or Mahāyānasaṃgraha, is one of the greatest works expounding the Yogacara teachings of Mahayana. It is also an incrediblefeat of translation, done by master translator and scholar Karl Brunnholzl.

The Mahāyānasaṃgraha, published here with its Indian and Tibetan commentaries in three volumes, presents virtually everything anybody might want to know about the Yogācāra School of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It discusses in detail the nature and operation of the eight kinds of consciousness, the often-misunderstood notion of “mind only” (cittamātra), dependent origination, the cultivation of the path and its fruition in terms of the four wisdoms, and the three bodies (kāyas) of a buddha.

Volume 1 presents the translation of the Mahāyānasaṃgraha along with a commentary by Vasubandhu. The introduction gives an overview of the text and its Indian and Tibetan commentaries, and explains in detail two crucial elements of the Yogācāra view: the ālaya-consciousness and the afflicted mind (klistamanas).

Volume 2 presents translations of the commentary by Asvabhāva and an anonymous Indian commentary on the first chapter of the text. These translations are supplemented in the endnotes by excerpts from Tibetan commentaries and related passages in other Indian and Chinese Yogācāra works.

Volume 3 includes appendices with excerpts from other Indian and Chinese Yogācāra texts and supplementary materials on major Yogācāra topics in the Mahāyānasaṃgraha.

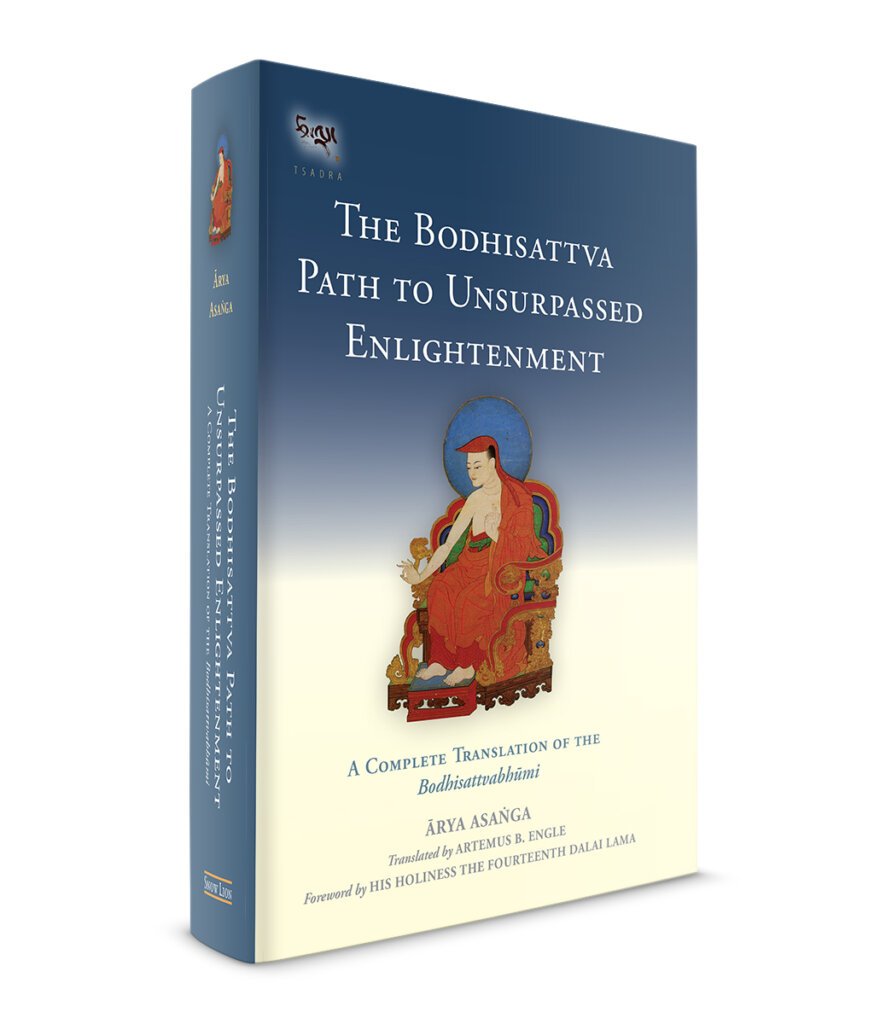

Hardcover | Ebook

$59.95 - Hardcover

The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpassed Enlightenment: A Complete Translation of the Bodhisattvabhumi

By Asanga, translated by Artemus Engle

Ārya Asanga’s Bodhisattvabhūmi, or The Stage of a Bodhisattva, is the Mahāyāna tradition’s most comprehensive manual on the practice and training of bodhisattvas—by the author’s own account, a compilation of the full range of instructions contained in the entire collection of Mahāyāna sutras. A classic work of the Yogācāra school, it has been cherished in Tibet by all the historical Buddhist lineages as a primary source of instruction on bodhisattva ethics, vows, and practices, as well as for its summary of the ultimate goal of the bodhisattva path—supreme enlightenment.

Despite the text’s seminal importance in the Tibetan traditions, it long remained unavailable in English except in fragments. Engle’s translation, made from the Sanskrit original with reference to the Tibetan translation and commentaries, will enable English readers to understand more fully and clearly what it means to be a bodhisattva and practitioner of the Mahāyāna tradition.

A Deep Dive on the Bodhisattvabhumi

Once you have a copy of The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpassed Enlightenment, a great complement to reading the book is to watch translator and scholar Artemus Engle discuss the work in detail, offering great context. Watch the preview here for a taste, and then jump right into the two talks, free to all.

Overview and Trailer

Part I, 1.5 Hours

Part II, 2 Hours

The Five Maitreya Texts

See also our two interviews on these texts with Karl Brunnholzl and Thomas Doctor of the Dharmachakra Translation Committee.

In Peaceful Heart, Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche recounts the story of how Asanga met Maitreya and received the teachings that come down to us as The Five Maitreya texts:

Asanga isolated himself in strict retreat, devoting all his time to practices related to Maitreya. His hope was for Maitreya to appear before him and give him instructions that would lead him to enlightenment. But after six years of diligent practice with no results, Asanga got frustrated and left. On his way home, he met a man who was rubbing a large iron bar with a soft piece of cloth. When Asanga asked what he was doing, the man said he was making a needle. Amazed at the effort people go through to accomplish futile aims, Asanga realized he needed to be more persistent on his path to enlightenment. So he returned to his retreat, determined never to give up. But three years later, when Maitreya still hadn’t appeared, not even in a dream, Asanga again left. This time he met a man who was stroking a massive boulder with a feather dipped in water. The man told him that he wanted to wear away the boulder because it was blocking the sunlight from his house. This gave Asanga renewed determination to keep persevering with his practice. But still Maitreya didn’t come.

Another uneventful and discouraging three years passed. Finally, Asanga left again and began to wander around, feeling hopeless and lost. He saw a crippled dog dragging herself along the road. Her rotting body was infested with maggots that were eating her flesh. Full of pain and aggression, the dog barked viciously at Asanga when he came closer. The sight broke Asanga’s heart. He thought about how to remove the maggots. If he used his hands, the maggots would probably be crushed, so the only way was to use his tongue. Disgusted by the rotting flesh, Asanga closed his eyes and stretched out to lick the maggots out of the dog. But as far as he stretched, he still didn’t feel the maggots. Finally, he felt his tongue touch the ground. He opened his eyes. Instead of the dog, Maitreya stood before him.

"How little compassion you have!" Asanga burst out. "I practiced for twelve years, and you didn’t even appear in my dreams!” Maitreya said, “Since the very first day of your retreat, I’ve been right there with you, but you didn’t have the openness to see me. Your twelve years of practice made your obscurations thinner. Today, your pure compassion for this dog finally made you open enough to see me in person. If you don’t believe me, put me on your shoulder and walk around.” Asanga put Maitreya on his shoulder and walked around at a fair, asking people what they saw on his shoulder. No one saw anything. They just thought he was crazy. Finally, an old woman, who also had developed enough openness to have higher perceptions, asked, “Why are you carrying a rotten dog on your shoulder?"

From then on, Maitreya imparted the teachings which we now know as The Five Maitreya Texts.

The Ornament of Clear Realization: The Abhisamayālaṃkāra

The Abhisamayalamkara summarizes all the topics in the vast body of the Prajnaparamita Sutras. Resembling a zip-file, it comes to life only through its Indian and Tibetan commentaries. Together, these texts not only discuss the "hidden meaning" of the Prajnaparamita Sutras—the paths and bhumis of sravakas, pratyekabuddhas, and bodhisattvas—but also serve as contemplative manuals for the explicit topic of these sutras—emptiness—and how it is to be understood on the progressive levels of realization of bodhisattvas. Thus these texts describe what happens in the mind of a bodhisattva who meditates on emptiness, making it a living experience from the beginner's stage up through buddhahood.

The Ornament of Clear Realization

Karl Brunnholzl discussing the two Gone Beyond volumes on the Kagyu tradition and the Ornament of Clear Realization and Groundless Paths which is the Nyingma take on the same work

Hardcover | Ebook

$54.95 - Hardcover

Gone Beyond (Volume 1)

The Prajnaparamita Sutras, The Ornament of Clear Realization, and Its Commentaries in the Tibetan Kagyu Tradition

By Asanga, Maitreya, the Fifth Shamar Rinpoche, and Karl Brunnholzl

Gone Beyond contains the first in-depth study of the Abhisamayalamkara (the text studied most extensively in higher Tibetan Buddhist education) and its commentaries in the Kagyu School. This study (in two volumes) includes translations of Maitreya's famous text and its commentary by the Fifth Shamarpa Goncho Yenla (the first translation ever of a complete commentary on the Abhisamayalamkara into English), which are supplemented by extensive excerpts from the commentaries by the Third, Seventh, and Eighth Karmapas and others. Thus it closes a long-standing gap in the modern scholarship on the Prajnaparamita Sutras and the literature on paths and bhumis in mahayana Buddhism.

The first volume presents an English translation of the first three chapters of the Abhisamayalamkara and its commentary by the Fifth Shamarpa.

Hardcover | Ebook

$44.95 - Hardcover

Gone Beyond (Volume 2)

The Prajnaparamita Sutras, The Ornament of Clear Realization, and Its Commentaries in the Tibetan Kagyu Tradition

By Asanga, Maitreya, the Fifth Shamar Rinpoche, and Karl Brunnholzl

The second volume presents an English translation of the final five chapters and their commentary by the Fifth Shamarpa.

Hardcover | Ebook

$54.95 - Hardcover

Groundless Paths: The Prajnaparamita Sutras, The Ornament of Clear Realization, and Its Commentaries in the Tibetan Nyingma Tradition

By Asanga, Maitreya, Patrul Rinpoche, Mipham Rinpoche, and Karl Brunnholzl

This study consists mainly of translations of Maitreya's famous text and two commentaries on it by Patrul Rinpoche. These are supplemented by three short texts on the paths and bhumis by the same author, as well as extensive excerpts from commentaries by six other Nyingma masters, including Mipham Rinpoche. Thus this book helps close a long-standing gap in the modern scholarship on the prajñaparamita sutras and the literature on paths and bhumis in mahayana Buddhism.

The Ornament of Mahayana Sutras: The Māhayānasūtrālaṃkāra

Padmakara's Stephen Gethin on the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra

A discussion of the Feast of the Nectar of the Supreme Vehicle and the importance of Mipham Rinpoche's commentary.

Hardcover | Ebook

$54.95 - Hardcover

A Feast of the Nectar of the Supreme Vehicle: An Explanation of the Ornament of the Mahayana Sutras

By Asanga, Mipham Rinpoche. Translated and introduced by the Padmakara Translations Group

A monumental work and Indian Buddhist classic, the Ornament of the Mahāyāna Sūtras (Mahāyānasūtrālamkāra) is a precious resource for students wishing to study in-depth the philosophy and path of Mahāyāna Buddhism. This full translation and commentary outlines the importance of Mahāyāna, the centrality of bodhicitta or the mind of awakening, the path of becoming a bodhisattva, and how one can save beings from suffering through skillful means.

This definitive composition of Mahāyāna teachings was imparted in the fourth century by Maitreya to the famous adept Asanga, one of the most prolific writers of Buddhist treatises in history. Asanga’s work, which is among the famous Five Treatises of Maitreya, has been studied, commented upon, and taught by Buddhists throughout Asia ever since it was composed.

In the early twentieth century, one of Tibet’s greatest scholars and saints, Jamgön Mipham, wrote A Feast of the Nectar of the Supreme Vehicle, which is a detailed explanation of every verse. This commentary has since been used as the primary blueprint for Tibetan Buddhists to illuminate the depth and brilliance of Maitreya’s pith teachings. The Padmakara Translation Group has provided yet another accessible and eloquent translation, ensuring that English-speaking students of Mahāyāna will be able to study this foundational Buddhist text for generations to come.

Distinguishing the Middle from Extremes: The Madhyāntavibhāga

This text explains the vast paths of all three yanas, emphasizing the view of Yogācāra (including the Yogācāra Middle Way) and the distinctive features of the mahāyāna.

Paperback | Ebook

$22.95 - Paperback

Middle Beyond Extremes: Maitreya's Madhyantavibhaga with Commentaries by Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham

By Asanga, Khenpo Shenga, Mipham Rinpoche. Translated and introduced by the Padmakara Translations Group

This text employs the principle of the three natures to explain the way things seem to be as well as the way they actually are. It is presented here alongside commentaries by two outstanding masters of Tibet’s nonsectarian Rimé movement, Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham.

Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature : The Dharmadharmatāvibhāga

This text discusses the difference between samsaric confusion and the liberating power of nonconceptual wisdom-the heart essence of all profound sutras.

Paperback | Ebook

$18.95 - Paperback

Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature: Maitreya's Dharmadharmatavibhanga with Commentaries by Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham

By Asanga, Maitreya, Khenpo Shenga, Mipham Rinpoche. Translated and introduced by the Dharmachakra Translation Committee

Outlining the difference between appearance and reality, this work shows that the path to awakening involves leaving behind the inaccurate and limiting beliefs we have about ourselves and the world around us and opening ourselves to the limitless potential of our true nature.

By divesting the mind of confusion, the treatise explains, we see things as they actually are. This insight allows for the natural unfolding of compassion and wisdom. This volume includes commentaries by Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham, whose discussions illuminate the subtleties of the root text and provide valuable insight into the nature of reality and the process of awakening.

Paperback | Ebook

$24.95 - Paperback

Adorning Maitreya’s Intent: Arriving at the View of Nonduality

By Asanga, Maitreya, Rongtonpa, introduced and translated by Christian Bernert

Here, the Tibetan master Rongtön unpacks this manual and its practices for us in a way that is at once accessible and profound, with actual practical meditative applications. The work explains the vast paths of the three vehicles of Buddhism, emphasizing the view of Yogācāra, and demonstrates the inseparability of experience and emptiness. It offers a detailed presentation of the three natures of reality, an accurate understanding of which provides the antidotes to confusion and suffering. The translator’s introduction presents a clear overview of all the concepts explored in the text, making it easy for the reader to bridge its ideas to actual practice.

Hardcover | Ebook

$39.95 - Hardcover

Mining for Wisdom within Delusion: Maitreya's Distinction between Phenomena and the Nature of Phenomena and Its Indian and Tibetan Commentaries

By Asanga, Maitreya, Vasabandhu, Gö Lotsāwa, The Third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje, . Translated and introduced by Karl Brunnholzl.

Maitreya’s Distinction between Phenomena and the Nature of Phenomena distinguishes the illusory phenomenal world of saṃsāra produced by the confused dualistic mind from the ultimate reality that is mind’s true nature. The transition from the one to the other is the process of “mining for wisdom within delusion.” Maitreya’s text calls this “the fundamental change,” which refers to the vanishing of delusive appearances through practicing the path, thus revealing the underlying changeless nature of these appearances. In this context, the main part of the text consists of the most detailed explanation of nonconceptual wisdom—the primary driving force of the path as well as its ultimate result—in Buddhist literature.

The introduction of the book discusses these two topics (fundamental change and nonconceptual wisdom) at length and shows how they are treated in a number of other Buddhist scriptures. The three translated commentaries, by Vasubandhu, the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, and Gö Lotsāwa, as well as excerpts from all other available commentaries on Maitreya’s text, put it in the larger context of the Indian Yogācāra School and further clarify its main themes. They also show how this text is not a mere scholarly document, but an essential foundation for practicing both the sūtrayāna and the vajrayāna and thus making what it describes a living experience. The book also discusses the remaining four of the five works of Maitreya, their transmission from India to Tibet, and various views about them in the Tibetan tradition.

Paperback | Ebook

$24.95 - Paperback

Maitreya's Distinguishing Phenomena and Pure Being

By Asanga, Maitreya, and Mipham Rinpoche. Translated by Jim Scott under the guidance of Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso.

Maitreya’s Distinction between Phenomena and the Nature of Phenomena distinguishes the illusory phenomenal world of saṃsāra produced by the confused dualistic mind from the ultimate reality that is mind’s true nature. The transition from the one to the other is the process of “mining for wisdom within delusion.” Maitreya’s text calls this “the fundamental change,” which refers to the vanishing of delusive appearances through practicing the path, thus revealing the underlying changeless nature of these appearances. In this context, the main part of the text consists of the most detailed explanation of nonconceptual wisdom—the primary driving force of the path as well as its ultimate result—in Buddhist literature.

The introduction of the book discusses these two topics (fundamental change and nonconceptual wisdom) at length and shows how they are treated in a number of other Buddhist scriptures. The three translated commentaries, by Vasubandhu, the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, and Gö Lotsāwa, as well as excerpts from all other available commentaries on Maitreya’s text, put it in the larger context of the Indian Yogācāra School and further clarify its main themes. They also show how this text is not a mere scholarly document, but an essential foundation for practicing both the sūtrayāna and the vajrayāna and thus making what it describes a living experience. The book also discusses the remaining four of the five works of Maitreya, their transmission from India to Tibet, and various views about them in the Tibetan tradition.

The Sublime Continuum: The Uttaratantra Śāstra

Also known as the Ratnagotravibhāga Mahāyānottaratantraśāstra, this is a general commentary on buddha nature and represents a bridge between sutra and tantra.

Hardcover | Ebook

$49.95 - Hardcover

When the Clouds Part: The Uttaratantra and Its Meditative Tradition as a Bridge between Sutra and Tantra

By Asanga, Karl Brunnholzl, Mipham Rinpoche, Pema Karpo, Mönlam Tsültrim, Eighth Karmapa, Jamgon Kongtrul and more.

This book discusses a wide range of topics connected with the notion of buddha nature as presented in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism and includes an overview of the sūtra sources of the tathāgatagarbha teachings and the different ways of explaining the meaning of this term. It includes new translations of the Maitreya treatise Mahāyānottaratantra (Ratnagotravibhāga), the primary Indian text on the subject, its Indian commentaries, and two (hitherto untranslated) commentaries from the Tibetan Kagyü tradition. Most important, the translator’s introduction investigates in detail the meditative tradition of using the Mahāyānottaratantra as a basis for Mahāmudrā instructions and the Shentong approach. This is supplemented by translations of a number of short Tibetan meditation manuals from the Kadampa, Kagyü, and Jonang schools that use the Mahāyānottaratantra as a work to contemplate and realize one’s own buddha nature.

Paperback | Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

Buddha Nature: The Mahayana Uttaratantra Shastra with Commentary

By Maitreya, Asanga, Jamgon Kongtrul, Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso, translated by Rosemarie Fuchs

All sentient beings, without exception, have buddha nature—the inherent purity and perfection of the mind, untouched by changing mental states. Thus there is neither any reason for conceit nor self-contempt. This is obscured by veils that are removable and do not touch the inherent purity and perfection of the nature of the mind. The Mahayana Uttaratantra Shastra, one of the “Five Treatises” said to have been dictated to Asanga by the Bodhisattva Maitreya, presents the Buddha’s definitive teachings on how we should understand this ground of enlightenment and clarifies the nature and qualities of buddhahood. This seminal text details with great clarity the view that forms the basis for Vajrayana, and especially Mahamudra, practice.

Paperback | Ebook

$39.95 - Paperback

Study and Practice of Meditation

Tibetan Interpretations of the Concentrations and Formless Absorptions

By Leah Zahler

Study and Practice of Meditation gives a vivid and detailed account of the meditative practices necessary to develop a calm, alert mind that is capable of penetrating the depths of reality. The Buddhist meditative states known as the concentrations and formless absorptions are best known in the West from Theravada scriptures and from Vasubandhu’s Treasury of Manifest Knowledge. Asanga's Summary of Manifest Knowledge (abhidharmasamuccaya, mngon pa kun btus) and his Grounds of Hearers (śrāvakabhūmi, nyan sa)also feature heavily.

In this book the reader is exposed to Tibetan Buddhist views on the mental states attained through meditation as described by three Geluk lamas. The book discusses the ways in which certain meditative states act as bases of the spiritual path as well as the nature of meditative calm and the prerequisites for cultivating and attaining it. In addition to reviewing and translating Tibetan sources, the author considers their major Indian antecedents and draws comparisons with Theravadin presentations.

Additional Resources on Asanga

On Lotsawa House Asanga appears in many translations, generally as a figure in a prayer.

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

Jamgon Kongtrul on the Creation Phase

Kongtrul discusses many details of the creation-phase practice, including suitable places, times and durations of practice, and the materials required for practice. For general purposes, most tantras advise staying “in a place that is secluded and pleasant” to accomplish general purposes. They also describe the types of places to be used for specific purposes. Kongtrul recommends that, above all, the place one chooses be a region in consonance with one’s own disposition. As for the times for practice, Kongtrul points out that most beginners will more easily achieve clarity in visualization by cultivating the practice at night. Once such clarity has been stabilized, one can meditate at any time. While in retreat, the practitioner must never be without certain essentials, such as qualified assistants, ritual articles, nourishing food and drink and adequate clothing. More than anything, the practitioner needs fortitude, which Kongtrul defines as “unrelenting perseverance that, despite adverse circumstances and even at the risk of one’s life, is never relaxed until the intended goal has been achieved.”

Kongtrul then describes the actual practice of the creation phase. He outlines the steps needed to prepare the practitioner for the main practice: the offering of sacrificial food to dispel interferences; the visualization of a circle of protection; generating the mind of awakening to develop positive potential; and meditating on emptiness to cultivate pristine awareness.

The main practice begins with the creation of the celestial palace of residence. According to most tantras, the base for the creation of the palace is the visualization of a tetrahedral dharmodaya and the tiers of the four elements. The celestial palace itself is generated from a syllable, an insignia, or the melting of a deity’s form. Some tantras describe charnel grounds along with particular trees, guardians, and so on, to be imagined outside the celestial palace.

The next step is the creation of the entire array of the resident deities. Three main procedures are followed: creation by means of the five actual awakenings; creation in four vajra steps; and creation by means of three vajra rites.

Creation by means of the five awakenings entails five steps that represent the five pristine awarenesses. The first is the generation of a moon, referred to as “awakening by means of mirror-like pristine awareness”; the second, of a sun, “awakening by the pristine awareness of sameness”; the third, of the seed-syllable and insignia, “awakening by the discerning pristine awareness”; the fourth, the merging of all these elements, “awakening by the pristine awareness of accomplishment”; and fifth, the full manifestation of the deity’s body, “awakening by the pristine awareness of the ultimate dimension of phenomena.”

Creation in four vajra steps entails meditation on emptiness; generating a moon, sun, and seed-syllable from which light emanates and then converges; the full manifestation of the deity resulting from the convergence of the light and transformation of the seed-syllable; and visualization of three syllables at the deity’s three places.

Creation by means of three vajra rites involves imagining the deity’s seed-syllable; the seed-syllable’s transformation into the deity’s insignia; and the insignia’s transformation into the full manifestation of the deity’s body.

The majority of tantras include the step known as the placement of the three beings, the pledge-being, the pristine-awareness-being, and the contemplation-being. The pledge-being means the particular deity generated through the ritual, that is, the deity who is the object of meditation. At the heart of the pledge deity is the pristine-awareness-being, imagined as a deity identical to the pledge deity; as a deity differing from the pledge deity in colour, appearance, or number of faces and arms; or as an insignia arisen from a seed-syllable. At the heart of the pristine-awareness-being is the contemplation-being, visualized as the seed-syllable or insignia. In some tantras, the placement of the three beings is enacted for all the deities; in others, for only the principal deities.

Kongtrul also reveals a number of steps that complete the creation-phase meditation. The step of absorbing the pristine-awareness mandala into oneself dispels the notion that oneself and the pristine-awareness deities are separate, and reinforces the “pride” of being indivisible from them. Conferral of initiation cleanses oneself of impurities and establishes the potency required to accomplish the ultimate goal of the tantra. The different types of sealing, such as the deity being sealed by the lord of a buddha family, ensure that meditation is carried out without misidentification. The tasting of nectar, offering, and praise, for which there are many variations from one tantra to the next, bring about the understanding that all objects of experience, the sensory pleasures, and so forth, are the pure expressions of bliss and emptiness.

Kongtrul explains that all the varieties of the creation phase incorporate the four key elements of form, imagination, result, and transformative power. “Form” means meditating on forms that represent the aspects of awakening and generating clear images of these forms, thereby stopping impure appearances. “Imagination” means using the force of creative imagination to convert the visualized forms of awakening into reality. “Result” means meditating on the result, that is, the very goal to be attained, and thereby achieving that goal. “Transformative power” means turning the ordinary body and mind into pristine awareness by relying on the transformative powers of awakened beings. Among these, Kongtrul points out, the most important element for realization of the path is the transformative power of the vajra master combined with one’s own devotion to that master.

In addition to those four key elements, creation-phase practice requires the development of clarity in visualization. To that end, one repeatedly brings forth clear images in both the coarse and subtle aspects of visualization. Moreover, one practices the meditation while firmly identifying with the deity. As one trains in the phase of creation, one must understand that the entire mandala is like an illusion, devoid of inherent nature, ultimately emptiness. Finally, one must manifest the pristine awareness in which the appearance of the deity (along with the certainty of being the deity) arises unceasingly as the essence of bliss and emptiness.

The practitioner who grows tired from the effort of visualizing the deity is advised to introduce a new element: the recollection of the pure nature of the deity. This means to recall the symbolic meanings of the different elements in the visualization, which represent the great qualities of the buddhas. For example, in meditation on Avalokiteshvara, one would recall that his single face symbolizes the single taste of all phenomena, his four arms symbolize the four boundless qualities of love, compassion, joy, and equanimity, and so on. Bringing to mind the purity of these attributes counteracts the notion that the attributes of the path and those of the result are different.

The phase of creation ends with the dissolution of the visualization. The mandala residence and resident deities dissolve into oneself. Then, one dissolves gradually into luminous clarity, once again to emerge as the deity.

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Eight, Part Three

$44.95 - Hardcover

By: Elio Guarisco & Ingrid Loken McLeod & Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Understanding the "Four Orders" of Tibetan Buddhism

Being identified with one of the four orders—Geluk, Kagyu, Nyingma, or Sakya—may say less about one’s practices than we think, according to Ngawang Zangpo, translator of Jamgon Kongtrul’s The Treasury of Knowledge: Books 2-4: Buddhism’s Journey to Tibet, in this adaptation from his translator’s postscript.

The Treasury of Knowledge: Books Two, Three, and Four

$49.95 - Hardcover

The four orders of Tibetan Buddhism are, simply put, institutions—containers that house diverse scriptural transmissions and lineages of meditation techniques. The institutions were likely founded with the intent to preserve and promote specific scriptures and meditations, yet those institutions’ missions invariably evolved over the centuries. For example, while Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa, and Milarepa—non-monks all—might view with astonishment the many Kagyu monastic networks erected in their name, Gampopa, Dusum Kyenpa, Pamo Drupa, and the others who founded those networks might be equally amazed at their modern content. What a strictly Kagyu practitioner learns today as the lineage’s core curriculum of theory and practice would hardly have been considered kosher in the founding fathers’ day.

To identify anyone as affiliated with one of the four orders is fair—we all start somewhere. In Kalu Rinpoché’s case, he joined a Kagyu monastery during his adolescence and he would sometimes add the prefix “Karma” to his name in veneration of the Karmapa and his lineage. Nevertheless, after his early training, his three-year retreat course consisted of mostly non-Karma Kagyu meditations, and in his post-retreat-graduate period of education and meditation, he seems to have treated Tibetan Buddhism as a self-serve buffet from which he slowly but surely tried and savored just about everything. Some of us had the impression that at some point he reached the end of the path, about which he was fond of saying, “There is no such thing as a Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, or Géluk enlightenment, just enlightenment.” He worked tirelessly to give back to the institutions, mainly Kagyu, that had given him so much over the years, but he found it tiresome and limiting to be regarded as a Kagyu Buddha, even among a stellar group of other equally misidentified Kagyu, Nyingma, Sakya, and Géluk buddhas.

Among “organized religions,” Buddhism is the least organized, but I do not mean to suggest that its Tibetan strain has descended into chaos and anarchy. Yet if one is only armed with the organizing principle of “four orders,” one will soon be confronted with many inconvenient facts of lived faith that are clearly incompatible with that framework. If one instead learns and retains the eight lineage template, everything that may have seemed incongruous and haphazard in Himalayan meditation practice can be understood as part of a larger, coherent system. It is this system that Kongtrul introduces to us here, to the detriment of the four-order scheme, which does not merit a single explicit mention in this chapter.

The four-order scheme can be useful as long as its field of usage is identified and that it is wielded gently and mindfully. It is not a precision instrument. My personal preference is to mentally adopt the Chinese names for the four Tibetan orders. In the place of our transliterated Tibetan names—Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, and Géluk—the Chinese use their own words for the four: red, multicolored, white, and yellow. These terms seem like code, and they are in fact ingenious in that they identify all we can know for sure without further enquiry concerning any specific monastery: the color of its exterior walls. (To explain “multicolored,” Sakyas paint a single horizontal, multicolored stripe around their buildings.) When I meet a Nyingma, all I can safely assume about her is that she and her spiritual community gather to learn, reflect, meditate, and worship in a red building; if Géluk, in a yellow one. That system has the virtues of simplicity, ease of use, and accuracy, but I don’t expect it to gain any currency: we are not yet close enough to Tibet to comfortably call things by our own names.

Ngawang Zangpo (Hugh Leslie Thompson) completed two three-year retreats under the direction of the late Kalu Rinpoche. He is presently working on a number of translation projects that were initiated under the direction of Chadral Rinpoche and Lama Tharchin Rinpoche. He has also contributed to Kalu Rinpoche's translation group's books Myriad Worlds and Buddhist Ethics.

Books by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

The Treasury of Knowledge: Systems of Buddhist Tantra, Book 6, Part 4

The following excerpts are taken from the introduction by Elio Guarisco to The Treasury of Knowledge, Book 6: Systems of Buddhist Tantra, by Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Tayé, translated by Ingrid Loken McLeod and Elio Guarisco

The following excerpts are taken from the introduction by Elio Guarisco to The Treasury of Knowledge, Book 6: Systems of Buddhist Tantra, by Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Tayé, translated by Ingrid Loken McLeod and Elio Guarisco

The Meaning of Tantra

To those who would embark on a quest for awakening, the Tibetan traditions of Buddhism offer three markedly different and seemingly incompatible sequences of practices: the individual way (hinayana); the universal way (mahayana); and the tantric way or secret mantra way (mantrayana).

While finding its foundation in the idealism (vijnanavada) and centrism (madhyamika) trends of thought, the tantric way undoubtedly sprang from the irresistible drive to know the nature of experience directly, unmediated by cognitive interpretation or emotional confusion. Consequently, it relies on an awareness that is an expression of the inner clarity present in our very being and not on knowledge derived from rational, philosophical, or conceptual processes.

Tantra consists of a skillful blending of three different types of practice: power methods, energy transformation methods, and intrinsic awareness methods. These methods came from a variety of sources and gradually formed into identifiable esoteric transmissions. Some practices were designed to break down social and cultural conditioning and others were developed to utilize basic energies in the body (including sexual energy) to enhance practice.

Etymologically, the word tantra is derived from the term for woof or weft, the thread that runs continuously through the fabric in traditional weaving methods. In Tibetan, the word means “continuum.” Both these meanings refer to the fundamental tantric perspective that the awareness that is the essence of being is always present, because it is not a thing, is not created, destroyed or subject to variation.