Meido Moore

Meido Moore Roshi was a disciple of the lay Zen master Tenzan Toyoda Rokoji, under whom he endured a severe training in both Zen and traditional martial arts. He also trained under Dogen Hosokawa Roshi, and later under So'zan Miller Roshi. All three of these teachers are in the lineage of the famous Omori Sogen Roshi, perhaps the most famous Rinzai Zen master of the twentieth century. Meido serves as abbot of Korinji, a monastery near Madison, Wisconsin, and is a guiding teacher of the international Rinzai Zen Community, traveling widely to lead retreats.

Meido Moore

GUIDES

An Excerpt from Hidden Zen

Gazing at Distant Mountains

The first practice we will examine is a bodily method of direct pointing. Specifically, it uses the eyes and vision to change our way of experiencing.

In Zen training, and particularly during zazen, the eyes are used in a specific manner that may be summarized thus: rather than staring at a single point using foveal (focused or central) vision, one activates the peripheral field to encompass one’s surroundings with awareness in a broad, sweeping, and relaxed manner. A traditional way this has been described in Japanese swordsmanship is that one should use the eyes “as if gazing at distant mountains.” Somewhat earlier in history, we have these words from the Fifth Patriarch.

Look to where the horizon disappears beyond the sky and behold the figure one. This is a great help. It is good for those beginning to sit in meditation, when they find their mind distracted, to focus their mind on the figure one.1

The character for the number one in Chinese is a single horizontal line. Advising students to look in this manner at the distant horizon is in fact the same thing as “gazing at distant mountains.” If you imagine how you might view at once a distant range of mountains, spread out from horizon to horizon—or visualize a single horizontal line spread out at the horizon where the earth meets the sky—the meaning of these words will become clear.

What is interesting is that when we use our eyes this way, we experience a marked decrease in gross thought activity: mental chatter stills. Examining more closely, we may observe that when using the eyes with attention in this manner there will seem to be little afflictive or negative emotion arising: our usual habit of giving rise to fear, craving, and other afflictive states lessens dramatically. Furthermore, we may notice that our sense of being an observing “self” separate from the things we see falls somewhat away. The sensation of existing inside one’s skull and watching objects that are outside in the world dissolves. Thus, the way we use our eyes in Zen practice can reveal our capacity for clarity and help us to experience samadhi. It can even lead us to awakening.

Over the years, I have heard my teachers stress again and again how crucial this way of using the eyes is. They have constantly reminded how important it is for correct zazen to integrate this manner of seeing. Reflecting further on the experience one has when seeing this way, I have come to an interesting conclusion: the modern habit of using the eyes almost entirely in a focused manner is an aberration, and not at all in accord with our physical evolution.

The way we use our eyes in Zen practice can reveal our capacity for clarity and help us to experience samadhi.

Most of our time these days seems to be spent with eyes tightly focused on screens. Even when walking outside we find it difficult not to pull out phones to continue indulging this habit. It is little wonder that we feel socially isolated and largely cut off from nature. One need only stroll down a city sidewalk to observe how most people walk with their fields of vision cast downward onto screens or the ground, avoiding the gaze of others and largely occupied with inner thoughts and worries. They will often walk right into you if you do not move to avoid them. Really, people who spend days and years like this cannot be said to be fully in the world at all. In a way, they are more like ghosts than living persons.

But for most of our development as a species I imagine that human beings moved through space and used their senses quite differently. Our distant ancestors lived in a world that required them to be fully present. Moving about on savannahs and plains or in deep forest, one must activate peripheral vision to sense activity and movement in the environment. This was necessary not only to find game but to avoid predators and enemies. Fine vision was also important, of course: to make a tool, to focus on a face when speaking, to examine something found. But I believe that for much of human history, peripheral vision was, in fact, equally important.

Hunters and others who observe wildlife still know this well today. If one wishes to find a deer in the woods or a bird in a tree, one does not search from point to point with focused vision. Instead one spreads out one’s gaze broadly, encompassing the whole scene within the peripheral field. The mind then becomes remarkably still and clear, and one feels immersed in or connected to the surroundings. In that state even a small flicker of movement—the flutter of a wing, the blinking of a deer’s eye, or the movement of its tail—is instantly sensed without effort or thought. Immediately and unconsciously, one then focuses in to determine what was glimpsed. Soldiers, police officers, and martial artists, if they are well trained, certainly also learn to integrate this way of using the eyes.

Many people spend large portions of their days with visual and mental focus strongly fixated upon a series of things but excluding from their attention most of the world around them.

That is all very interesting. But what we should especially understand as Zen practitioners is that overuse of focused vision increases tension, internal chatter, and neuroses. Yet everyone, not just practitioners, can relearn to spread out their vision. When we do so, whole new worlds of living detail and movement open for us. We begin to feel again that we are part of the space surrounding us rather than isolated within ourselves. Truly, we should all regain this original human way of seeing.

Despite the importance of using the eyes this way in Zen training, it oddly seems to be among the orally transmitted details of practice not always received by Western Zen students. I have even heard from some Zen students that their teachers advised them to stare one-pointedly at a fixed spot on the floor or wall, something that not only causes eyestrain and fatigue but also an increase in gross thought activity and tension. For these reasons I have placed this method first among the direct pointing practices.

Exercise #1

Here is an exercise you may try in order to grasp this physical way of using the eyes.

1. Sitting or standing comfortably, look straight ahead and spread out your vision in a broad, relaxed manner so that you are watching the entire room at once (rather than staring with focused vision at whatever point across the room your gaze strikes).

2. Extend your arms behind your head where you cannot see them and raise your index fingers to eye level. Slowly bring the arms forward until the fingers appear in your peripheral field. Stop at the point where you can just see both fingers at the same time on the very edges of your vision. Stretch your vision out to simultaneously encompass both fingers and the entire visual field between them. (Figure 1)

3. Now drop your arms but maintain this expansive gaze, stretching your awareness to the limits of the peripheral field and filling the surrounding space. You are not looking at one thing; you are seeing everything at once, softly and effortlessly.

If you wish to understand how this way of using the eyes is integrated within seated meditation, simply allow the angle of your gaze to drop to forty-five degrees while maintaining the expansive vision you cultivated. Though the eyes are gently downcast, your awareness still fills the space around you. The feeling is that even if a fly should land somewhere in the room, you will know it without having to shift your gaze.2 (Figure 2)

In daily life we should also use our vision this way whenever possible. As I have said, many people spend large portions of their days with visual and mental focus strongly fixated upon a series of things (screens, the ground, their food during meals, and so on) but excluding from their attention most of the world around them. Our way of using the eyes should more often have a sweeping, expansive quality, filling both horizontal and vertical space with this feeling of seeing the entire view at once.

Exercise #2

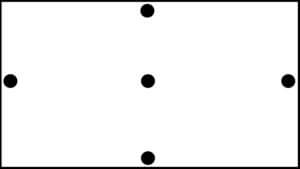

If you found the exercise using upraised fingers to be difficult, here is another simple one that uses this book you are holding. Using the diagram below, follow the instructions given. (Figure 3)

1. Looking straight ahead, hold this book up at eye level at a comfortable distance from your face such that you can stare intently at the center dot in the diagram. Doing so, restrict your attention solely to that dot: this replicates the experience of focused vision. In that state, now observe your condition of mind. Is it tense or tight in feeling?

2. Continuing to hold the book in that manner, now expand your attention to encompass the four outer dots simultaneously. Your vision is now being used a little more broadly. You are still aware of the center dot, but the other dots are now included in your field of awareness.

3. Expand your attention more broadly now to encompass the entire page. Once again, observe your condition of mind in that state.

4. Finally, without turning away or shifting your gaze, let your attention extend beyond the edges of the book. Keep the book where it is, but simply expand your attention to encompass the room beyond the page that is in front of and around you. You will notice that you are still aware of both the center and outer dots, and the book itself, but your vision does not stick to them and softly takes in the entire surroundings as well. Observe your condition of mind now: it will feel even more free and relaxed.

Direct Pointing

Once you have gained some familiarity with this way of using the eyes, there are many ways to apply it. Here is a practice of direct pointing using this way of broad, expansive seeing.

1. Go to a place in which you have some open space in front of you, for example, facing out toward a distant view, an open field, or a horizon where the waters of a sea or lake meet the sky. Stand or sit comfortably, relaxing the body. Let your chin be level so that you are looking straight ahead. You may raise your chin slightly if it helps to establish such an expansive view.

2. Take a few deep breaths naturally in and out through the nose, letting all tension drop from body and mind.

3. When you are ready, now take a final deep breath and exhale slowly. As you exhale, and especially at the end of your exhalation when the breath has mostly exited but before you feel the need to inhale, immediately and strongly spread out your vision to the very limits of your peripheral field. Do this with full attention for five or ten seconds. (The exact length of time is unimportant.) You may continue to breathe naturally during this time as required.

4. Now relax and recall those few seconds when you spread your vision out, examining your experience:

-

- Were there thoughts arising or the usual mental chatter during that time you spread your vision out?

- Did any negative or afflictive states arise during that time? Were there any habitual feelings of fear, craving, anxiety, sadness, and so on?

- Was there, in fact, any “I” present within that expansive awareness?

If you are able to catch the intent of this method, you will likely recognize that there is actually little or no gross thought activity during the time you spread out your vision. For those few moments, there are no negative states or feelings arising. And there is little or no solid sense of “I” within it; there is seeing, but the sense of a watcher engaged in the activity of viewing separate “things” is not strongly present at all. Just this reveals your own capacity for clarity and the ultimately boundless nature of your mind, not restricted by habitual dualistic seeing.

Watch a Video of this Practice

Notes

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Zen Buddhism: A History, India and China (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1988), 101.

- In Rinzai practice students face toward the center of the room, and so the center of one’s gaze will naturally rest lightly on the floor. In Soto practice, commonly done facing a wall, the gaze will of course rest there. But whichever method one uses, the instructions given here apply: one should not stare at the point upon which the gaze falls but spread out one’s vision to encompass the entire peripheral field.

Share

Related Books

The Approach and Intent of Zen | An Excerpt from The Rinzai Zen Way

Understanding the Rinzai Zen Way

Studying Zen, one rides all vehicles of Buddhism; practicing Zen, one attains awakening in a single lifetime.

—Eisai

[From a teisho given in February 2012]

In speaking with many beginning Zen students, it seems apparent that although they may be familiar with some of the methods of Zen practice, what is often lacking is an understanding of the overall approach and intent of the Zen way. Without this understanding it will be difficult to follow the path of our practice and arrive at its fruition. For this reason, I want to speak simply about these things in a manner that is easy to grasp.

The Description of What Zen Is

Bodhidharma handed down to us a famous four-line description of what Zen is. I should say this description is attributed to Bodhidharma since we do not know whether it originally comes from him. But the important thing is that these lines express Zen’s understanding of itself, so they should be understood by those of us who are Zen practitioners.

But the important thing is that these lines express Zen’s understanding of itself, so they should be understood by those of us who are Zen practitioners.

The four lines are as follows:

A separate transmission outside the scriptures.

Not dependent upon words or letters.

Direct pointing at the human mind.

Seeing one’s nature and becoming Buddha.

Let us take a look at each of these lines.

A separate transmission outside the scriptures means that the lifeblood of Zen practice lies within the relationship between teacher and student. Our way, though it does not conflict with the essential meaning of the sutras, is not actualized through them. How is it actualized? Within your own body, and specifically through the joining together of your mind with that of your teacher. This vital human relationship within which Zen is transmitted and made to live is what “outside the scriptures” affirms.

Not dependent upon words or letters means that while the sutras, commentaries, records of the Zen patriarchs and other Buddhist writings all point to the awakening and its actualization, which are the Zen path, these texts (as well as writings of value from other traditions) must ultimately be viewed as descriptions of awakening or realization. That is to say, one might not be able to awaken simply by reading the descriptions. They are hints, pointers, maps. But they are not themselves to be relied upon or set up as sufficient, except inasmuch as you are able to make them come alive within your own body.

In other words, all of these writings arose out of someone’s actual experience and are attempts to explain and describe that experience. This is important and crucial and helpful. These things have great usefulness on the path. In the course of Zen practice, we especially use the sutras and other writings to check our insight; at some point in our training, we must ensure that our experience is in accord with what has been written in the past. However, that insight itself must first be arrived at experientially in our own bodies, rather than intellectually.

These first two lines, then, reveal Zen’s general approach: the transmission of Zen occurs “mind to mind” within the vital, intimate relationship between teacher and student. Furthermore, the wisdom to which Zen points—and the path of its embodiment—may be described within the Buddhist writings but will not be completed through intellectual understanding alone.

Seeing One’s Nature

This last point reminds me of an opportunity I had to participate in an interfaith dialogue at a Catholic center. Our focus was specifically the modern dialogue between Buddhist and Catholic monastics, which had been pioneered by Thomas Merton. While preparing for this event, I read something I had never known about Thomas Aquinas, the great theologian and philosopher. Near the end of his life, while performing mass, it is said that Aquinas heard the voice of Christ speaking to him. Christ, expressing that he was well pleased with Aquinas, asked him what he desired. Aquinas replied, “Only you, Lord,” negating and dropping himself completely.

At that moment, Aquinas had a deeply transforming experience. He was later unable to describe it but refused to continue working and writing in the normal manner. When asked to do so, he declared, “Everything I have written now seems to me as straw.”

I found this story moving. It reminded me of Tokusan, who wrote a commentary on the Diamond Sutra and, packing this on his back, traveled to southern China, intending to discredit the Zen teachings. Upon experiencing his own breakthrough, however, he burned his treasured treatise, saying, “Even if we have mastered all the profound teachings, it is no more than a single hair in the vastness of space.”

Truly, all else pales before the actual experience of awakening. Yet until we arrive at that intimate knowledge, how easy it is to delude ourselves into thinking that we understand what Zen is. If even people of great ability and potential like Tokusan have fallen into such traps, how much more so each of us must be careful not to rest satisfied with a shallow understanding.

Truly, all else pales before the actual experience of awakening. Yet until we arrive at that intimate knowledge, how easy it is to delude ourselves into thinking that we understand what Zen is.

The Actual Approach of Zen Practice and the Intent of the Zen Way

Now let us consider the second pair of Bodhidharma’s lines, which reveal the actual approach of Zen practice and affirm the intent of the Zen way.

Direct pointing at the human mind refers to the many skillful means by which Zen students are led to kensho, the recognition of one’s true nature—that is, the nature of one’s mind as not different from what is meant by Buddha—which is the entrance gate of Zen. We may say that fundamentally it is the Zen teacher’s job to cause the student to discover this intrinsic wisdom.

There are many examples of such direct pointing in Zen writings. Rinzai said, “Upon this lump of red flesh [that is, within your own body] is the true human being of no rank. It is constantly moving in and out of the gates of your face. Those of you who have not seen it, look!” The Sixth Patriarch said, “Thinking of neither good nor evil [that is, putting down the habit of dualistic seeing], what is your original face?”

From the day you begin your Zen training, you receive many such “direct pointings” through various means depending on the ability and style of the teacher. All the many forms of our practice—the ways we are taught to move, walk, and sit; the ways in which the sounds of instruments and voices are used; encounters with our teachers—can be methods of direct pointing. A good teacher, in fact, is constantly pointing out the essential meaning of Zen to you.

Of course, we are not all sharp enough to catch it right away. We may have many obstructions to awakening, which can be physical, energetic, conceptual, and so on. So at the same time that we are receiving many forms of direct pointing, we may also learn various practices to dissolve our obstructions. Again, it is fundamentally the Zen teacher’s job to prescribe such practices that fit our situations.

The fourth line begins with the words Seeing one’s nature—that is, awakening to the nature of mind. This is the moment when we actually do recognize that which is constantly being pointed out to us. Deep or shallow, this turning around of the light of awareness to recognize one’s “original face” marks the entrance into Zen. This is kensho.

Before kensho, we do commonly say that we practice Zen. But in truth we should know that we have not yet actually, in our own existence, affirmed Zen. It is more accurate at that point to say we are doing Buddhist practice. But it is not yet really Zen.

Before kensho, we do commonly say that we practice Zen. But in truth we should know that we have not yet actually, in our own existence, affirmed Zen. It is more accurate at that point to say we are doing Buddhist practice. But it is not yet really Zen.

And what happens when we have indeed passed through this gate of kensho? Everything is fine, right? No, not yet. There is still the second half of this last line: becoming Buddha. These final words call us not only to give testament to the truth of our nature, which is boundless, but also to fully actualize this awakening, to integrate it, to embody it, and so to realize all the activities of body, speech, and mind in accord with it.

Only such embodiment is what we call “becoming Buddha.” Simply having the recognition of our nature does not mean that we have actualized the full fruition of awakening. The lifelong practice of liberation, which is the real meat and core of the Zen way, still lies ahead. Certainly, though, having gained the confidence of our own experience, we may expect our faith, our energy, and our commitment to deepen from the moment we enter the gate of Zen awakening. This is a special quality of the Zen approach, which takes awakening as both the entrance to the path and the path itself.

This concludes a brief summary of Zen’s general approach and intent. It is not difficult to understand this. It is not even particularly difficult to enter the gate of kensho. But to actualize kensho along the lifelong path of liberation can, in fact, be quite difficult.

How to do it, then? Simply follow the instructions of your teacher, give yourself body and mind to the training, and follow the path of practice that has been clearly laid out by the masters of the past. Rely upon your teacher and community, and just throw yourself into it!

This has been excerpted from The Rinzai Zen Way: A Guide to Practice.

Related Books