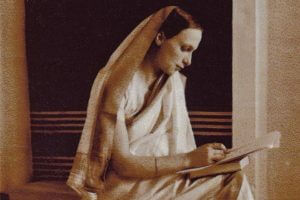

Vicki Mackenzie

Vicki Mackenzie is a professional journalist and author who has written for the national and international press for over 40 years. Her articles have appeared in The Sunday Times, The Observer, The Daily and Sunday Telegraph, the Daily Mail, and many national magazines. She has written extensively on Buddhist topics and was the first person to publish an interview with the Dalai Lama for The Sunday Times. She has been studying and practicing Buddhism since 1976.

Vicki Mackenzie

GUIDES

Freedom Fighter | An Excerpt from The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi

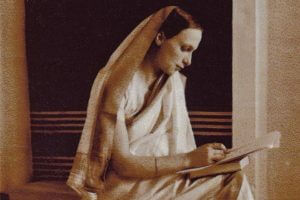

She was the first Western woman to become a Tibetan Buddhist nun—but that pioneering ordination was really just one in a life full of revolutionary acts. Freda Bedi (1911–1977) broke the rules of gender, race, and religion—in many cases before it was thought that the rules were ready to be challenged. Vicki Mackenzie gives a nuanced view of Bedi and of the forces that shaped and motivated this complex and compelling figure. Please enjoy this excerpt from The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi!

Freda's Mission

Her home and working life established, Freda threw herself wholeheartedly into her mission to free India from imperialism and to bring justice and equality to the poor and downtrodden. She traveled all over the Punjab by foot, often taking Ranga with her, going from village to village, absorbing the land and its people, raising their consciousness about the struggle for freedom. She stayed in their huts, ate their food, learned their songs, and heard their problems. Now, rather than being confined to merely looking in and talking as she had as an Oxford undergraduate, she was in a position to act.

This intimacy heightened her love of India and whetted her revolutionary zeal. “India is in a very bad way and constitutions, for all the fuss made over them, are not going to help at all. It will need something more radical. When you get into the homes of the peasants—unbelievable poverty! They live on three paisa per day—one penny, at a liberal estimate—everything inclusive. They are just ground down by starvation and the moneylender,” she wrote to Olive. Later, she added, “India has harrowed me with her festering poverty, her dirt, and her despair, and I have become a unit of the ragged army that fights against it.”

Freda’s compassion and admiration for the peasants never wavered. In her eyes they were noble souls, living a truer existence, in harmony with the soil and the rhythms of the seasons, unsullied by materialism. “Modern people would probably put security at the top of the list of what makes them happy, but the peasant is humbler and simpler in the face of the inevitable insecurities of nature and of life. The villagers, the ‘illiterates’ of India, have got that genius of simple people; they judge not from words but from the heart, from feelings, from gestures, from instinct. It is we who have been blunted by words, not they who are dull.”

Again her affinity with women—especially mothers—was strong. “Many times I have been confronted with a village woman and her child and she has given one look at me and my little boy, and we have been friends from that minute. There is something in the understanding of a woman and a woman, of a mother and a mother, which is far beyond language or skin. It is a feeling often ‘too deep for tears,’ born of common hopes, and prayers, and sufferings.”

“Many times I have been confronted with a village woman and her child and she has given one look at me and my little boy, and we have been friends from that minute. There is something in the understanding of a woman and a woman, of a mother and a mother, which is far beyond language or skin. It is a feeling often ‘too deep for tears,’ born of common hopes, and prayers, and sufferings.”

Freda’s Agenda of Reform

Her agenda was twofold: to urge “the warrior peasants of the Punjab” to agitate for land reform and fairer land revenues, and to demand their civil liberties, especially against the heartless Indian police officers, who regularly beat them. She would then bring this terrible treatment to the attention of the authorities.

Word quickly spread of the Englishwoman, dressed in a sari, and her audiences grew from a few stragglers to vast crowds, curious to see and hear this phenomenon for themselves. “When I say that in those days I addressed not just thousands but hundreds of thousands of villagers, I am not telling an untruth. It became part of my way of life. The Punjab peasant became not only familiar to me but a friend.”

A far greater challenge was addressing the students and nationalists in Lahore, but BPL urged her to do it. “He said it was nothing, that I should think of it as if I were addressing the debating society at Oxford. The first time I spoke, I was petrified. There were twenty-four thousand people waiting. And these twenty-four thousand people had very definite opinions about what they should and shouldn’t listen to. If they didn’t like the speaker, they were well known for beating the ground with shoes and sticks.

“I stood on the platform like a martyr awaiting execution and decided to speak very loudly into the loudspeaker. I can still hear the shock that went through the whole mass of twenty-four thousand heads when this rather slight, Western-looking woman suddenly bellowed at them. I found out I could go on speaking and not be drummed out of existence by sticks and shoes.”

Her True Voice

Freda had well and truly found her voice—an unusual thing for any woman of any era. She was extremely accomplished in her native tongue and loved words, but to give a speech in Hindi (albeit with a British accent) was a remarkable accomplishment. The audience was rightly mesmerized by this woman of the Raj and the wife of one of the biggest landowners of the Punjab, who was urging them on to rebellion. Decades later, people could still recall the power of her oratory. After her inaugural speech there was thunderous applause and cries of, “We want freedom.”

The audience was rightly mesmerized by this woman of the Raj and the wife of one of the biggest landowners of the Punjab, who was urging them on to rebellion. Decades later, people could still recall the power of her oratory. After her inaugural speech there was thunderous applause and cries of, “We want freedom.”

Her speeches especially resonated with the women, who took courage from Freda’s own example. Freda records how the women of Srinagar ran out in the streets, rattled stones, and frightened the soldiers’ horses. “The women became the heroines. Village women would take a club on their shoulder and stride at the head of the village ‘armies.’ There was nothing dynamic or fiery in their timid faces. But I knew inside me this was woman’s shell. When the time came, these women would be on the streets again, never faltering, throwing their powerhouse of energy into another great movement of the people. Women put their proverbial patience to many uses. They know how to wait.”

Inevitably, the authorities reacted. Everyone in The Huts lived in a constant state of tension and anxiety. The Huts were constantly threatened with demolition; Freda and BPL (and those who associated with them) were under constant surveillance and were frequently harassed by the police.

“Being a socialist in India is no joke. We all of us live on the edge of jail, and however careful you are, nothing much can be done if you do get arrested, since legal rights are rather pre-Cromwell. It is very difficult to present a picture of these terrifying days,” Freda wrote to Olive.

The Tension Surrounding Them

Ranga still remembers the tension that surrounded them all. “Mummy was trailed by plainclothed policemen all the time. In order to get her removed from her job, Fateh Chand College was subjected to all sorts of harassment and sudden inspections, but the school never submitted. It was extremely brave of them, as harboring a political activist was a punishable act. No other college dared employ her, even though a master’s degree from Oxford was no

mean qualification for a woman in India.

“They even questioned the sweepers to see if she was teaching sedition! Once, when a sweeper was taken down to the police station and manhandled, my mother marched off with me in tow and took the police inspector to task. She then insisted on making a notation in the complaint book. That evening a British police officer visited the college and threatened to arrest her. She wrote to the police hierarchy in Lahore and sent copies to the newspapers. Mummy was absolutely fearless at all times!”

It was the threat of prison, however, that most unnerved Freda. All the A-list agitators, including of course Nehru and Gandhi, were constantly being hauled before judges and jailed. BPL was no exception. He was first arrested in 1937 for some provocative speech at an outdoor meeting, and Freda soon became reconciled to the pattern. It was part of the deal they had signed up for, and what they actually wanted in order to promote their cause. As he had warned as part of his marriage proposal, Freda spent a lot of time visiting him behind bars. Once again she was stoic.

“It is not unduly oppressive and often there are some enlightened Indian officers in charge who are nationalists at heart, and so don’t give the prisoners a hard time. Of course, imprisonment is imprisonment, and it’s a suffering not be allowed to go out and lead a normal life. But BPL is cheery and philosophical, and usually has one or two good friends in jail with him. My mother-in-law, because of her age and generation, suffers even more than I do about this. We are great friends, and her loving presence makes a great difference.”

A Turn toward Civil Disobedience

By 1939, the revolution was heating up, and under Bose’s influence, freedom fighters were favoring violence as the means to achieve their goal. This was too much for Freda, who promptly turned her attention totally to Gandhi and his peaceful approach of civil disobedience. BPL, however, jumped right in with added fervor and was promptly arrested for dangerous political activity and sentenced to four years in Deoli Prison (infamous for coining the term doolally, signifying “crazy”).

Deoli was grim, situated in the middle of the Rajasthan desert, miles from anywhere, and enclosed within three layers of barbed wire and numerous watchtowers. An escapee would have to walk days before reaching the nearest village.

It was the longest sentence BPL had been given and the hardest for Freda to bear, not only because she was left alone without moral and physical support from her husband but also because she rightly knew that BPL would continue to agitate behind bars. She lived in a constant state of worry and fear for him.

Now unable to live independently in The Huts because it was too dangerous, she got permission to move into one of Fateh Chand College’s hostels, taking Ranga with her. Children were not allowed into the hostels, but Freda was popular with students and staff alike, having won their admiration and respect. Again, the college bravely agreed. With plenty of staff only too happy to look after (and spoil) Ranga, Freda was free to continue her full teaching program and carry on with her own revolution.

Wracked with anxiety about BPL in Deoli, Freda constantly badgered the prison authorities for the right to visit him. After much string pulling from two barrister friends practicing in the Punjab High Court, Freda finally got a permit for a “family” visit. She took Ranga with her. It turned into a saga of high comic drama.

Ranga recalled, “Mummy and I set off in the blistering heat traveling by train, third class, as she always insisted. It took days, with us staying at small wayside hotels, eating at bus stops and having to report to various police stations along the way. All the time Mummy was harassed so that she would abandon the trip. Finally we were put down beside a dirt track and, after an hour’s walk, arrived at Deoli Detention Camp, which was run by the army, not the police. They had no information regarding our visit and were visibly put out by the sight of Mummy in Indian clothes, the British wife of a dangerous political criminal.

“Mummy and I set off in the blistering heat traveling by train, third class, as she always insisted. It took days, with us staying at small wayside hotels, eating at bus stops and having to report to various police stations along the way. All the time Mummy was harassed so that she would abandon the trip. Finally we were put down beside a dirt track and, after an hour’s walk, arrived at Deoli Detention Camp, which was run by the army, not the police. They had no information regarding our visit and were visibly put out by the sight of Mummy in Indian clothes, the British wife of a dangerous political criminal.

“After a short while we were escorted to the commandant, a strapping British colonel whose discomfiture was even greater than that of his juniors. He said he could not allow the visit without confirmation from headquarters. Furthermore, he continued, providing accommodation for a difficult prisoner’s wife and child or acquiring transport to the nearest town was out of the question. He didn’t know what to do with us. We could see he was rattled, and confused! At sundown he relented and conceded that we could stay in the officers’ suite and would be able to meet Papa the next morning, at nine, for one hour. In the end we were given the VIP treatment, including an invitation to dine in the officers’ mess hall. Mummy politely declined.

An Incident

“Mummy was up at first light, and after breakfast (served in our rooms) we were escorted back to the commandant. The atmosphere was tense. The colonel told us there had been an ‘incident.’ The political prisoners had gone on hunger strike and had had to be force-fed—with the exception of Mr. Bedi, who had aggressively resisted. They had been protesting against prison conditions, alleging it was being run like a concentration camp, with the inmates being denied the rights of political detainees.

“News of our visit had spread, and another attempt to force-feed BPL had been made at six o’clock that morning. Apparently eight people had gone to Papa’s room and found him to be calm and generally cooperative. They put together the feeding apparatus, with no protest from Papa. As the medical officer bent over him, Papa sprang into action. He kicked the attendant in the groin, carried him to the door, and threw him off the veranda, causing him to dislocate his shoulder. Two other guards were floored, and the others backed off.

“Mummy remained very calm. ‘Didn’t you know he holds the All India hammer-throwing record?’ she asked. Knowing we were there, Papa said he would eat voluntarily, but only if he could see us.’ Of the incident BPL remarked, ‘The battle lasted only two minutes, my honor was sustained.’”

The story became apocryphal among the Bedis.

“Mummy remained very calm. ‘Didn’t you know he holds the All India hammer-throwing record?’ she asked. Knowing we were there, Papa said he would eat voluntarily, but only if he could see us.’ Of the incident BPL remarked, ‘The battle lasted only two minutes, my honor was sustained.’”

Freda and Ranga finally found BPL the sole occupant of a tenfoot-square room, the last one in a long row in a barrack-like building. There was a mattress on the floor, no furniture or curtain at the window. The books they had brought him were confiscated. The meeting was warm but abysmally short. When they emerged, one of the escorting officers commented, “Mrs. Bedi, your husband is a very strong man.” Freda, polite as always and willing to connect with everyone, struck up conversation and was amazed to discover he was from Derbyshire.

After they left, BPL’s hunger strike continued for twenty-five days, during which time he received several beatings, which left permanent damage to his spine. He always walked with a cane after that.

A Turning Point for Freda

The visit marked a turning point in Freda’s life. Her marriage was founded on the vow to unite with BPL in his fight for Indian independence, whatever it took. She now decided to join him in jail. Having discussed the matter over with him in Deoli, she applied to become one of Gandhi’s handpicked satyagrahis, the select band of protestors who were willing to sacrifice everything, including their lives, to free India from colonial rule. It was the radical move, she told Olive, that was needed to get the job done and give the oppressed a voice. Freda was determined to live out her beliefs to the full, even if it meant leaving Ranga without both parents.

Conceived when Gandhi was working as a lawyer in South Africa, the Satyagraha movement was defined as the Force Born of Truth, Love, and Nonviolence. As his independence movement gathered increasing support, Gandhi rightly judged that a handpicked band of highly committed, disciplined individuals, his satyagrahis, would have a greater impact on public and official opinion than would mob unrest. Furthermore he would run less risk of losing control of them in the heat of the action. Freda explained, “The idea was that only the few would go to jail to protest for the many.”

It was a momentous decision, especially in light of the fact that they had already lost one child in the name of their political activities. Torn between compassion for the many and the care of her child, Freda chose the bigger picture. She reasoned that the many, suffering as they were under exploitation and poverty, had no one to champion them, whereas Ranga was surrounded by doting relatives, especially Bhabooji. In the end, as always, Freda followed the force of her convictions.

In the end, as always, Freda followed the force of her convictions.

“I didn’t want to make things worse on the domestic side, but on the other hand I felt I should back up the nationalist movement in whatever humble way I could, even if it meant suffering for some months in prison. I also wanted to support BPL and share what he was going through,” she reasoned.

Freda began to prepare. She arranged for BPL’s brother, the judge, to support her family financially while she was behind bars, and she also carefully explained to Ranga what she was going to do and why.

“Mummy swore me to secrecy. I couldn’t talk about it to anyone! I was really scared. I had this persistent raw feeling in the pit of my stomach. I remember one incident when Mummy took us to have our anti–cholera-and-typhoid injections and the doctor said, ‘Freda, it’s very wise to have these shots before offering Satyagraha,’ and the raw feeling intensified,” Ranga recalled.

Over the next few months she took her son back for extended visits to the family land at Dera Baba Nanak, where his paternal grandmother and her extended family were living, to acclimatize him to the impending separation. It was a clever move.

“I loved it at Bhabooji’s. I was given an endless supply of sweets, was allowed to stay up and sleep in late, and was given a pair of quails, and a parrot, and was made the sole egg collector. On my return to Fateh Chand College I could hardly wait for Mummy to go through with her plans.”

Accepted by Gandhi

Freda waited some time to be chosen, but she was finally accepted by Gandhi as his fifty-seventh satyagrahi—the first British woman to be admitted to his elite band. Instructions came: On no account was she to retaliate or resist if she were arrested or beaten. The main thrust of her protest, like that of all satyagrahis, was to speak out against “the crime” of involving India in Britain’s participation in World War II without first consulting the legislative assembly. Gandhi argued that to fight another nation’s war without personal choice was unacceptable. (Ironically, Freda seemed not to notice that Britain’s war was against fascism, the very thing that she, too, declared she loathed.)

She duly wrote to the district magistrate informing him that she intended to break the law by holding a mass rally during which she would urge the people not to support the military effort until India became a democracy and they could choose for themselves. But for all her outer composure, when the day came, Freda admitted she was scared.

“Suddenly I felt alone, agonizingly alone. I could have wept for my sheer aloneness. I wanted to talk to BPL, to have his cheery voice near me,” she said. “I suppose in all crises of our life we get that feeling of isolation as though we are treading a path into the future all alone, for all the love that surrounds us—when we first leave home, when we marry, when we have a choice to make at some crossroads of our life. Perhaps we feel like that when we are on the brink of death. And on the borders of that aloneness, there comes another feeling, of being given the strength to carry on, of not being alone anymore.”

“I suppose in all crises of our life we get that feeling of isolation as though we are treading a path into the future all alone, for all the love that surrounds us—when we first leave home, when we marry, when we have a choice to make at some crossroads of our life. Perhaps we feel like that when we are on the brink of death. And on the borders of that aloneness, there comes another feeling, of being given the strength to carry on, of not being alone anymore.”

Freda was buoyed up by the breadth of her vision, and the revolution she hoped she would ignite: “That spark will go on burning until it ignites a greater fire than the one from which it sprang. And you are the spark of a greater fire, although you barely know it,” she said.

The Biggest Protest

February 21, 1941, was the day Freda chose to make her biggest protest yet. However, in the hours beforehand, a comic cat-and-mouse game with the police was played out.

“First a local inspector arrived to inquire about her plans and to inform her she was being put under twenty-four-hour surveillance,” says Ranga. “Then several police surrounded the house and compound. Mummy’s response was to send tea and snacks out to them every few hours. In the meantime huge crowds were gathering, and the villagers, undeterred by the police presence, erected a small stage from which she could address the rally. The police tried to pull it down, but they could not get close enough. Their plan was to arrest her before she reached the stage.

“At four a.m., when it was still dark, the police burst into the house, but Mummy was nowhere to be found. They searched the surrounding farmhouses, but to no avail, so they started a rumor that she had already been arrested in the hope that the multitude would disperse. By now some forty thousand people had arrived by train, bullock cart, or on foot to witness an Englishwoman offering Satyagraha, and there was something of a carnival atmosphere.

“Mummy suddenly appeared, as if from nowhere. She had been hiding under the stage. It was the most dramatic event of my early life. Mummy was utterly calm, but I was shaking. She told the crowd that any form of violence or resistance to her arrest would defeat the cause and would deeply disappoint her, leading her to regard it as a failure of her mission. She went on to say she had chosen Dera because it was the home of Baba Nanak and the Bedi clan. Mummy then came over to me and gave me a big hug.”

Freda recounted, “A local policeman with a beard came forward politely. ‘Regretting it is my duty, but I must arrest you,’ he said. To his right was the English police inspector from Amritsar, who was there because they did not know how an Englishwoman might react when she was arrested. He was surprisingly small, in an unwieldy toupee and had a walrus mustache. He looked like Old Bill. I wanted to laugh, and the corners of my mouth twitched. ‘I am quite ready. Take me along with you,’ I said.”

It took Freda and the policemen at least thirty minutes to get through the throng, who were all shouting, “Freedom for India! Long live Gandhiji! Long live Comrade Bedi! Release the Detainees!” and were throwing garlands over the awaiting car. “Garlands are not allowed,” said Old Bill. The villagers peered wonderingly into the car as it sped Freda away.

At the police station the comedy continued. Following procedure, Old Bill asked her nationality. “English.” Where was she born? “Derby.” What color would she say her eyes were? “You might call them blue-gray.” She was taken swiftly on to the courtroom. The trial took fifteen minutes, with an embarrassed, red-faced young judge, fresh out of England, admitting to her, “I find this as embarrassing as you do.”

Freda looked directly into his eyes and replied, “Don’t worry, I don’t find it unpleasant at all. Treat me as an Indian woman and I will be quite content.”

After fumbling in his Defense of India rules book the judge handed her the sentence: six months’ rigorous imprisonment in Lahore female jail.

“Surely you mean Lahore Women’s Jail,” Freda replied archly, offended by his grammar.

The sentence was exceptionally harsh—no other satyagrahi was given as much. Freda reacted with customary composure, and with no anger or malice. There was even kindness. ‘Maybe it was because they wanted to make an example out of me, because I was English and the first Western woman to offer Satyagraha. Or maybe it was the ignorance of the young civil servant presiding at the trial. He gave the sentence regretfully and with many apologies. He was a decent sort of man,” she said.

Freda was just thirty years old when she went to jail. She had come a long way from the little watchmaker’s shop in Derby. In those years she had become a trailblazer, defying expectations and convention by marrying a Sikh, living in a left-wing commune, and raising literally thousands of people to insurrection by the power of her oratory—all in the name of humanity and justice.

This has been excerpted from The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi: British Feminist, Indian Nationalist, Buddhist Nun.

Share

Related Books