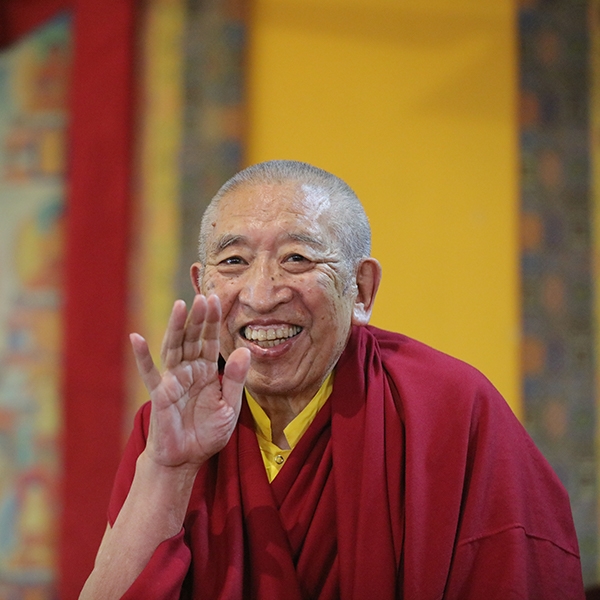

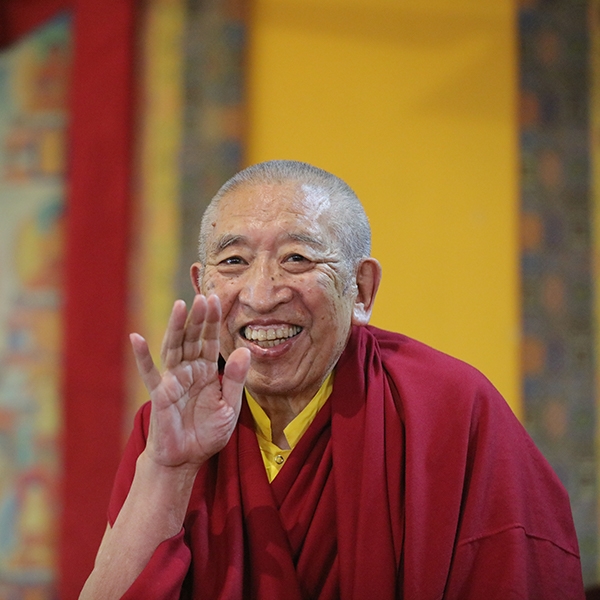

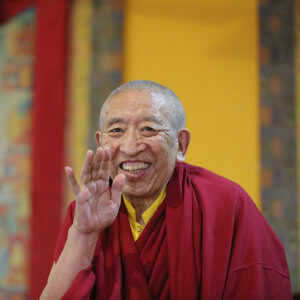

Khenchen Thrangu

Khenchen Thrangu is an eminent teacher of the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. He was appointed by the Dalai Lama to be the personal tutor for His Holiness the Seventeenth Karmapa and has authored many books, including Tilopa’s Wisdom, Naropa’s Wisdom, The Mahamudra Lineage Prayer, and Advice from a Yogi.

Khenchen Thrangu

-

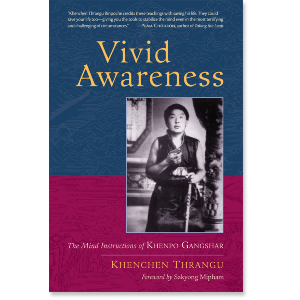

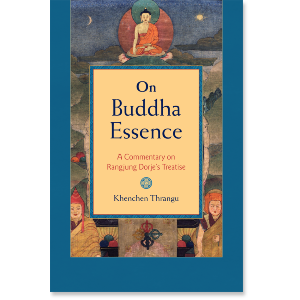

A Harmony of Views$21.95- Paperback

A Harmony of Views$21.95- PaperbackTranslated by Thrangu Dharmakara Translation Collab

By Khenchen Thrangu -

Advice from a Yogi$18.95- Paperback

Advice from a Yogi$18.95- PaperbackBy Khenchen Thrangu

By Padampa Sangye

Translated by Thrangu Dharmakara Translation Collab -

Pointing Out the Dharmakaya$22.95- Paperback

Pointing Out the Dharmakaya$22.95- PaperbackBy Khenchen Thrangu

Foreword by H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Translated by Lama Yeshe Gyamtso

Edited by Lama Tashi Namgyal -

Everyday Consciousness and Primordial Awareness$24.95- Paperback

Everyday Consciousness and Primordial Awareness$24.95- PaperbackBy Khenchen Thrangu

Edited by Susanne Schefczyk

Translated by Susanne Schefczyk -

The Ninth Karmapa's Ocean of Definitive Meaning$21.95- Paperback

The Ninth Karmapa's Ocean of Definitive Meaning$21.95- PaperbackBy Khenchen Thrangu

Edited by Lama Tashi Namgyal -

The Practice of Tranquillity and Insight$29.95- Paperback

The Practice of Tranquillity and Insight$29.95- PaperbackBy Khenchen Thrangu

Foreword by Clark Johnson

Translated by Peter Roberts

- Buddhist Overviews 1 item

- Healing in Buddhism 1 item

- Heart Sutra 1 item

- Abhidharma 1 item

- Bodhisattva Path 1 item

- Buddha Nature 1 item

- Dzogchen 1 item

- Kagyu Tradition 12item

- Karmapas 4item

- Mahamudra 9item

- Nyingma Tradition 2item

- Shamatha 3item

- Stages of Meditation 1 item

- Vipassana/Lhatong (Tibetan Specific) 2item

- Buddhist Psychology 1 item

GUIDES

Naropa: A Reader's Guide to the Great Master of Mahamudra

The following short biography of Naropa is adapted from Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism:

Naropa, Tilopa’s primary disciple, is born in wealthy circumstances, the favored son of a kshatriya (ruling caste in India) family. At seventeen, he is compelled by his parents to marry. After eight years of marriage, however, he announces his intention to renounce the world. He and his wife agree to a divorce, and Naropa, like Tilopa, takes ordination into the monastic way. Unlike Tilopa, however, Naropa invests many years in intensive study, mastering the major branches and varieties of Buddhist texts, including the Vinaya, Sutras, and Abhidharma of the Hinayana, the Prajnaparamita of the Mahayana, and the tantras. Eventually, he rises to the top of his religious profession, becoming first a high-ranking scholar at Nalanda and then its supreme abbot. His fame as a scholar spreads everywhere, and he is considered unexcelled in his understanding of Buddhist doctrine.

At Nalanda, he has an extraordinary experience with a seeming ordinary old woman but one who it turns out has a profound effect on his life and sends him to find Tilopa.

At this moment, Tilopa appears, a blue-black man dressed in cotton trousers, with a topknot and bulging bloodshot eyes. He declares that ever since Naropa formed the intention to seek him, Tilopa has not been separate from him and that it was only Naropa’s defilements that blinded him to this fact. He tells Naropa that he is a worthy vessel, will indeed be able to receive the deepest teachings, and that he will accept him as a disciple.

For the next twelve years, Naropa is Tilopa’s disciple, undergoing a most demanding tutelage. He suffers immensely through all kinds of physical, psychological, and spiritual trials, torments, and tribulations. The rigor of his training is in direct measure, he understands, to the karmic accretions and obscurations that he has accumulated in his previous lives. Each of Tilopa’s teachings is a catastrophe for Naropa’s sense of personal identity, and in each instance he believes himself to have been irreparably and mortally harmed. In each case Tilopa reveals a deeper level of Naropa’s being, one that is open, clear, and resplendent, independent of the life and death of ego. Throughout this period, Tilopa says very little, and Naropa’s instruction occurs in nonverbal ways, through his own pain and through symbolic gestures that he must assimilate. No security and certainly no confirmation are ever given, and Naropa is able to persevere out of complete devotion to Tilopa and his conviction that he has no other options.

After twelve years of training, one day Naropa is standing with Tilopa on a barren plain. Tilopa remarks that the time has now come for him to offer Naropa the much-sought-after oral instructions, the transmission of dharma. When Tilopa demands an offering, Naropa, who has nothing, offers his own fingers and blood. As Lama Taranatha recounts the event.

Then Tilopa, having collected the fingers of Naropa, hit him in the face with a dirty sandal and Naropa instantly lost consciousness. When he regained consciousness, he directly perceived the ultimate truth, the suchness of all reality, and his fingers were restored. He was now granted the complete primary and subsidiary oral instructions. Thereupon, Naropa became a lord of yogins.

From Tilopa, Naropa receives the transmissions of mahamudra, the six inner yogas, and the anuttara-yoga tantras, and himself becomes a realized siddha in the tradition of his master. Naropa is subsequently seen sometimes roaming through the jungles, sometimes defeating heretics, sometimes in male-female aspect (that is, in union with his consort, a mark of his realization), hunting deer with a pack of hounds, at other times performing magical feats, at still other times acting like a small child, playing, laughing, and weeping. As a realized master, he accepts disciples, and through all of his activities, however benign or unconventional and shocking they may be, he reveals the awakened state beyond thought, imbued with wisdom, compassion, and power. He is also a prolific author whose previous scholarly training enables him to be an eloquent writer on Vajrayana topics, evidenced by his works surviving in the Tenjur.

Naropa is a pivotal figure in the evolution of the Kagyu¨ lineage for the way in which he joins tantric practice and more traditional scholarship, unreasoning devotion and the rationality of intellect. Through him, Tilopa’s profound and untamed lineage is brought out of the jungles of east India and given a form which the Tibetan householder Marpa can receive.

Essential Texts by and about Naropa

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

Naropa's Wisdom: His Life and Teachings on Mahamudra

As the disciple of Tilopa and the guru of Marpa the Translator, Naropa is one of the accomplished lineage holders of the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. He expressed his realization in the form of spiritual songs, pithy yet beautiful poems that he sung spontaneously. In this book, Khenchen Thrangu, a contemporary Karma Kagyu master, first tells the story of Naropa’s life and explains the lessons we can learn from it and then provides verse-by-verse commentary on two of his songs. Both songs contain precious instructions on Mahamudra, the direct experience of the nature of one's mind, which in this tradition is the primary means to realize ultimate reality and thus attain buddhahood.

Thrangu Rinpoche’s teaching on the first song, The View, Concisely Put, explains the view of Mahamudra in a manner suitable for Western students who are new to the subject. The second song, The Summary of Mahamudra, contains all the key points of the view, meditation, conduct, and fruition of Mahamudra. Thrangu Rinpoche speaks plainly, directly, and without using any technical jargon to Westerners eager to learn the fundamentals of the Mahamudra path to enlightenment from a recognized master. As Thrangu Rinpoche says, “Mahamudra is a practice that can be done by anyone. It is an approach that engulfs any practitioner with tremendous blessings that make it very effective and easy to implement. This is especially true in our present time and especially true for Westerners because in the West there are very few obstacles in the practice of Mahamudra.”

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

Illusion's Game: The Life and Teaching of Naropa

In what he calls a "200 percent potent" teaching, Chögyam Trungpa reveals how the spiritual path is a raw and rugged "unlearning" process that draws us away from the comfort of conventional expectations and conceptual attitudes toward a naked encounter with reality. The tantric paradigm for this process is the story of the Indian master Naropa (1016–1100), who is among the enlightened teachers of the Kagyu lineage of the Tibetan Buddhism. Naropa was the leading scholar at Nalanda, the Buddhist monastic university, when he embarked upon the lonely and arduous path to enlightenment. After a series of daunting trials, he was prepared to receive the direct transmission of the awakened state of mind from his guru, Tilopa. Teachings that he received, including those known as the six doctrines of Naropa, have been passed down in the lineages of Tibetan Buddhism for a millennium.

Trungpa Rinpoche's commentary shows the relevance of Naropa's extraordinary journey for today's practitioners who seek to follow the spiritual path. Naropa's story makes it possible to delineate in very concrete terms the various levels of spiritual development that lead to the student's readiness to meet the teacher's mind. Trungpa thus opens to Western students of Buddhism the path of devotion and surrender to the guru as the embodiment and representative of reality.

Paperback | Ebook

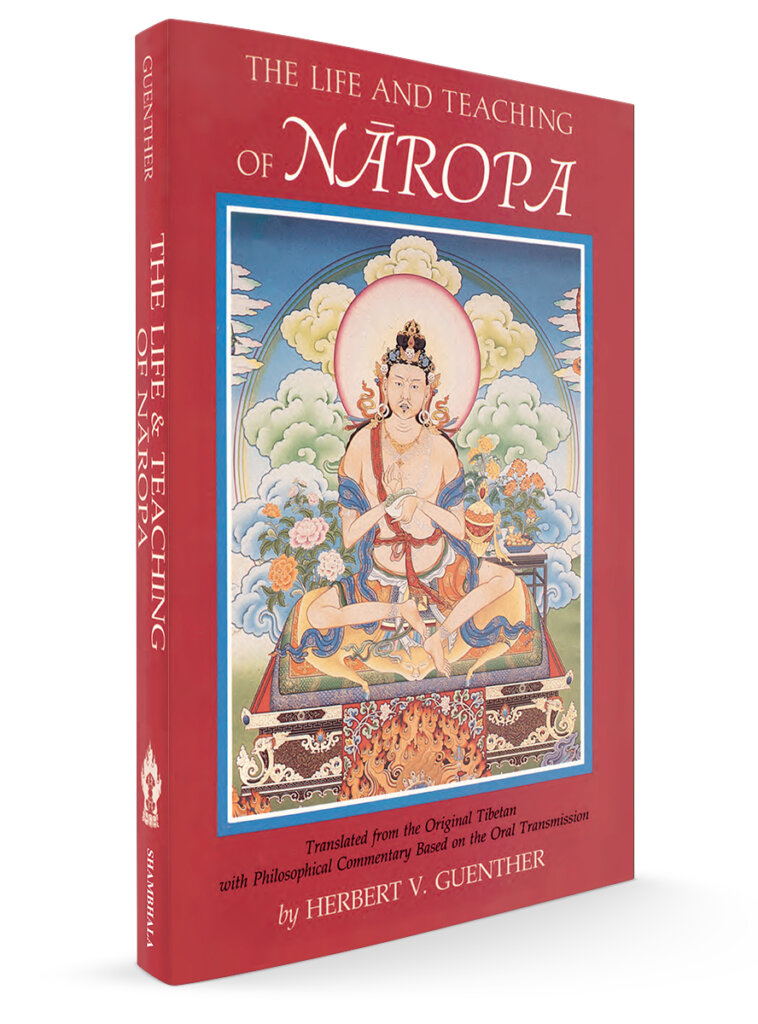

$34.95 - Paperback

The Life and Teaching of Naropa

Translated by Herbert V. Guenther

In the history of Tibetan Buddhism, the eleventh-century Indian mystic Nâropa occupies an unusual position, for his life and teachings mark both the end of a long tradition and the beginning of a new and rich era in Buddhist thought. Nâropa's biography, translated by the world-renowned Buddhist scholar Herbert V. Guenther from hitherto unknown sources, describes with great psychological insight the spiritual development of this scholar-saint. It is unique in that it also contains a detailed analysis of his teaching that has been authoritative for the whole of Tantric Buddhism.

This modern translation is accompanied by a commentary that relates Buddhist concepts to Western analytic philosophy, psychiatry, and depth psychology, thereby illuminating the significance of Tantra and Tantrism for our own time. Yet above all, it is the story of an individual whose years of endless toil and perseverance on the Buddhist path will serve as an inspiration to anyone who aspires to spiritual practice.

The Six Yogas of Naropa

The Six Yogas of Naropa

The Six Yogas of Naropa are a set of advanced tantric practices that can only be undertaken under the close guidance of a qualified teacher. We do not recommend these books unless one is under such guidance as misunderstanding is very likely.

Paperback | Ebook

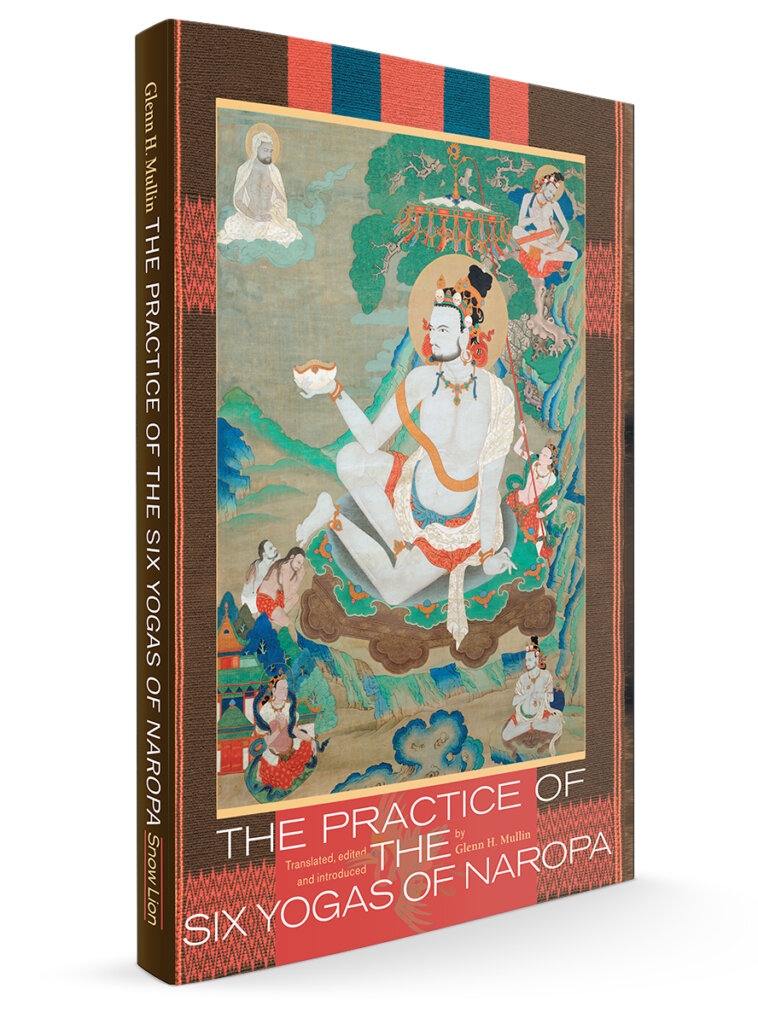

$27.95 - Paperback

The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa

Edited by Glenn Mullin

This book on the Six Yogas contains important texts on this esoteric doctrine, including original Indian works by Tilopa and Naropa and writings by great Tibetan lamas. It contains an important practice manual on the Six Yogas as well as other works that discuss the practices, their context, and the historical continuity of this most important tradition.

- The Oral Instruction of the Six Yogas by Tilopa

- Vajra Verses of the Whispered Tradition by Naropa

- Notes on "A Book of Three Inspirations" by Je Sherab Gyatso

- Handprints of the Profound Path of the Six Yogas of Naropa by Gyalwa Wensapa

- A Practice Manual on the Six Yogas of Naropa by Tsongkhapa

- The Golden Key: A Profound Guide to the Six Yogas of Naropa by the First Panchen Lama

Paperback | Ebook

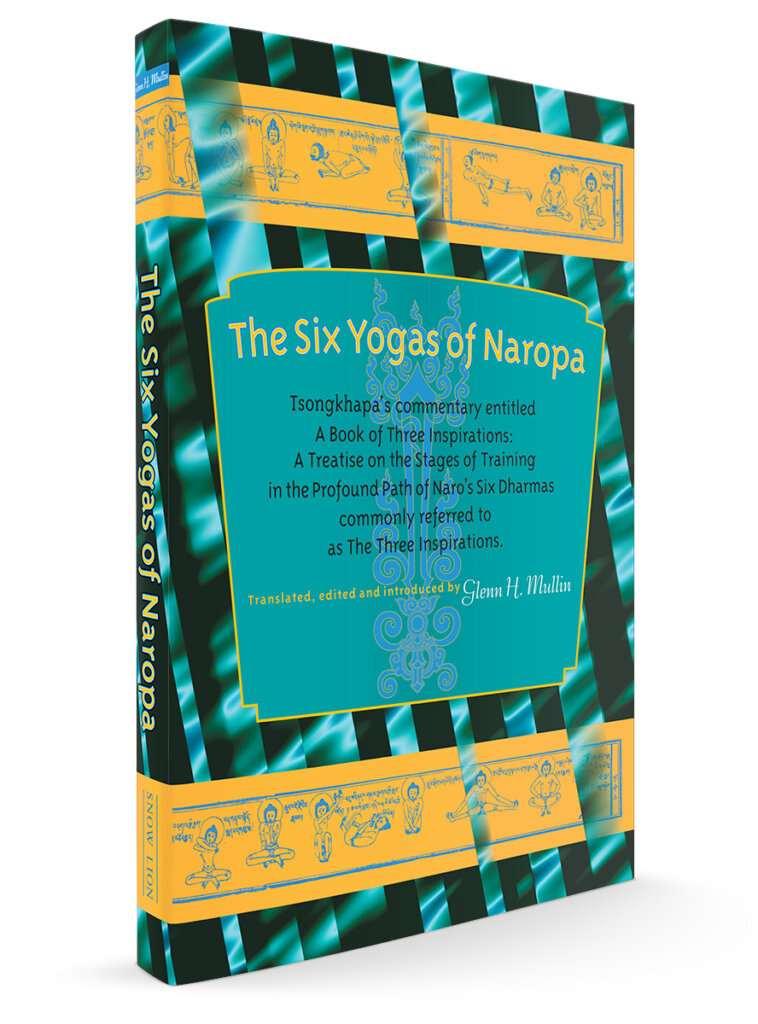

$39.95 - Paperback

The Six Yogas of Naropa: Tsongkhapa's Commentary

By Tsongkhapa, translated and introduced by Glenn Mullin

Tsongkhapa's commentary entitled A Book of Three Inspirations: A Treatise on the Stages of Training in the Profound Path of Naro's Six Dharmas is commonly referred to as The Three Inspirations. Anyone who has read more than a few books on Tibetan Buddhism will have encountered references to the Six Yogas of Naropa, a preeminent yogic technology system. The six practices—inner heat, illusory body, clear light, consciousness transference, forceful projection, and bardo yoga—gradually came to pervade thousands of monasteries, nunneries, and hermitages throughout Central Asia over the past five and a half centuries.

More Books Featuring Naropa

Paperback | Ebook

$27.95 - Paperback

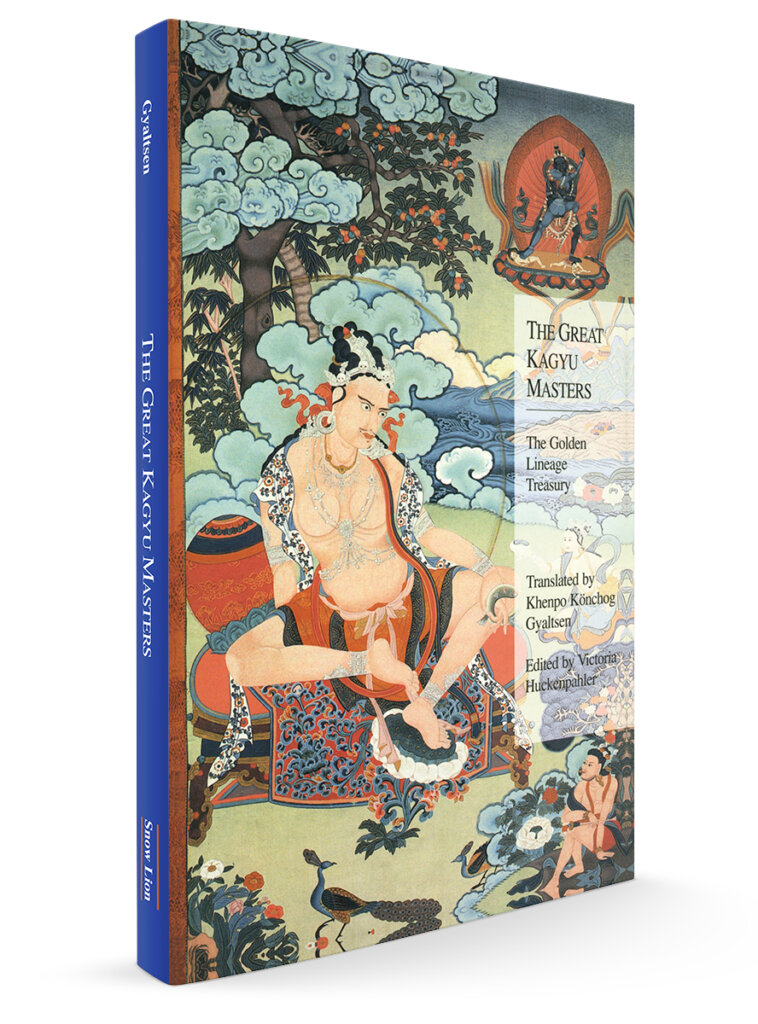

The Great Kagyu Masters: The Golden Lineage Treasury

Compiled by Dorje Dze Öd, translated by Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche

The Golden Lineage Treasury was compiled by Dorje Dze Öd a great master of the Drikung lineage active in the Mount Kailasjh region of Western Tibet. This text of the Kagyu tradition profiles and the forefathers of the tradition including Vajradhara, the Buddha, Tilopa, Naropa, the Four Great Dharma Kings of Tibet, Marpa, Milarepa, Atisha, Gampopa, Phagmodrupa, Jigten Sumgon, and more.

The chapter on Naropa is 45 pages long.

Hardcover | Ebook

$49.95 - Hardcover

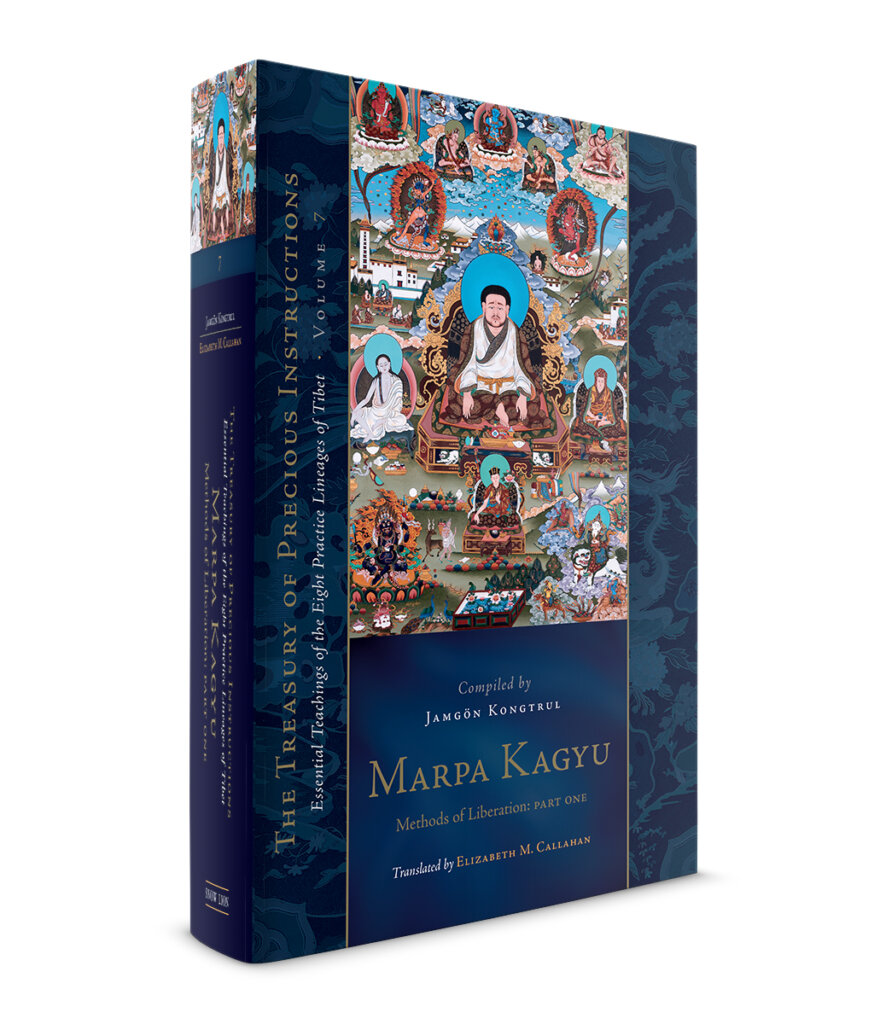

Marpa Kagyu, Part One - Methods of Liberation: Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 7

The Treasury of Precious Instructions

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye

The seventh volume of the series, Marpa Kagyu, is the first of four volumes that present a selection of core instructions from the Marpa Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. This lineage is named for the eleventh-century Tibetan Marpa Chokyi Lodrö of Lhodrak who traveled to India to study the sutras and tantras with many scholar-siddhas, the foremost being Naropa and Maitripa. The first part of this volume contains source texts on mahamudra and the six dharmas by such famous masters as Saraha and Tilopa. The second part begins with a collection of sadhanas and abhisekas related to the Root Cakrasamvara Aural Transmissions, which are the means for maturing, or empowering, students. It is followed by the liberating instructions, first from the Rechung Aural Transmission. This section on instructions continues in the following three Marpa Kagyu volumes. Also included are lineage charts and detailed notes by translator Elizabeth M. Callahan.

The piece by Naropa in this volume include:

- Summary Verses on Mahāmudrā

- Authoritative Texts in Verse: Mahāsiddha Nāropa’s Cycle on the Six

Dharmas - Vajra Song Summarizing the Six Dharmas: The Scholar-Mahāsiddha

Nāropa’s Instructions to the Lord of Yogins Marpa

Hardcover | Ebook

$24.95 - Hardcover

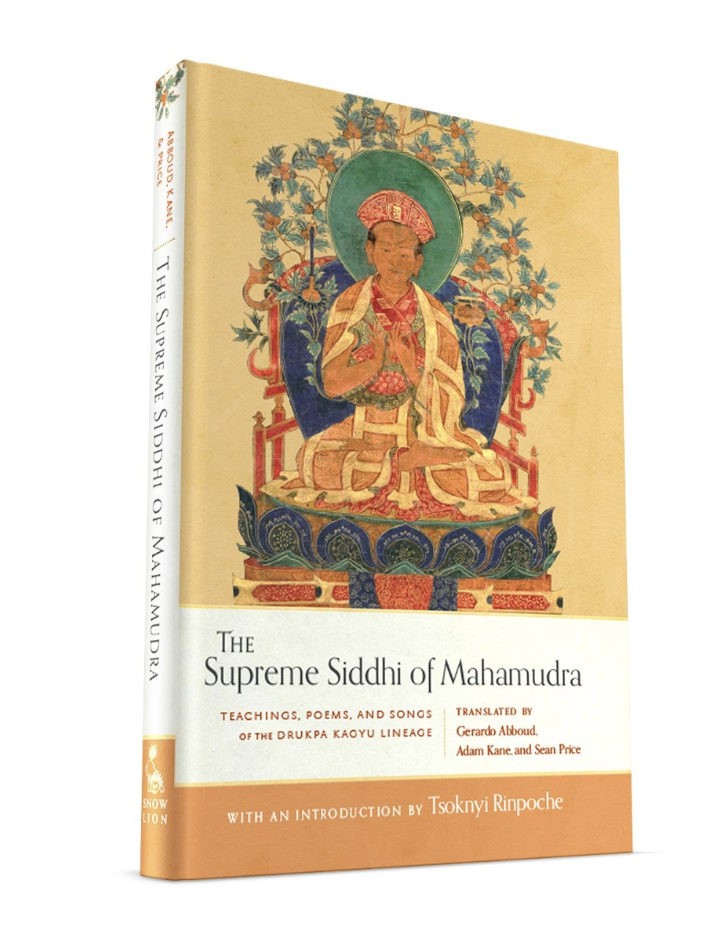

The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra: Teachings, Poems, and Songs of the Drukpa Kagyu Lineage

Translated by Gerardo Abboud, Sean Price, and Adam Kane

The Drukpa Kagyu lineage is renowned among the traditions of Vajrayana Buddhism for producing some of the greatest yogis from across the Himalayas. After spending many years in mountain retreats, these meditation masters displayed miraculous signs of spiritual accomplishment that have inspired generations of Buddhist practitioners. The teachings found here are sources of inspiration for any student wishing to genuinely connect with this tradition.

These translations include Mahamudra advice and songs of realization from major Tibetan Buddhist figures such as Gampopa, Tsangpa Gyare, Drukpa Kunleg, and Pema Karpo, as well as modern Drukpa masters such as Togden Shakya Shri and Adeu Rinpoche. This collection of direct pith instructions and meditation advice also includes an overview of the tradition by Tsoknyi Rinpoche.

The second chapter, on Naropa, is a translation of the Condensed Veses of Mahamudra, known in Sanskrit Mahāmudrāsaṃjñāsaṃhitā as and in Tibetan as (Chakgya Chenpo Tsig Dupa (Phyag rgya chen po’i tshig bsdus pa).

Combined with guidance from a qualified teacher, these teachings offer techniques for resting in the naturally pure and luminous state of our minds. As these masters make clear, through stabilizing the meditative experiences of bliss, clarity, and nonthought, we will be liberated from suffering in this very life and will therefore be able to benefit countless beings.

Translator on Gerardo Abboud on The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra

Hardcover | Ebook

$29.95 - Hardcover

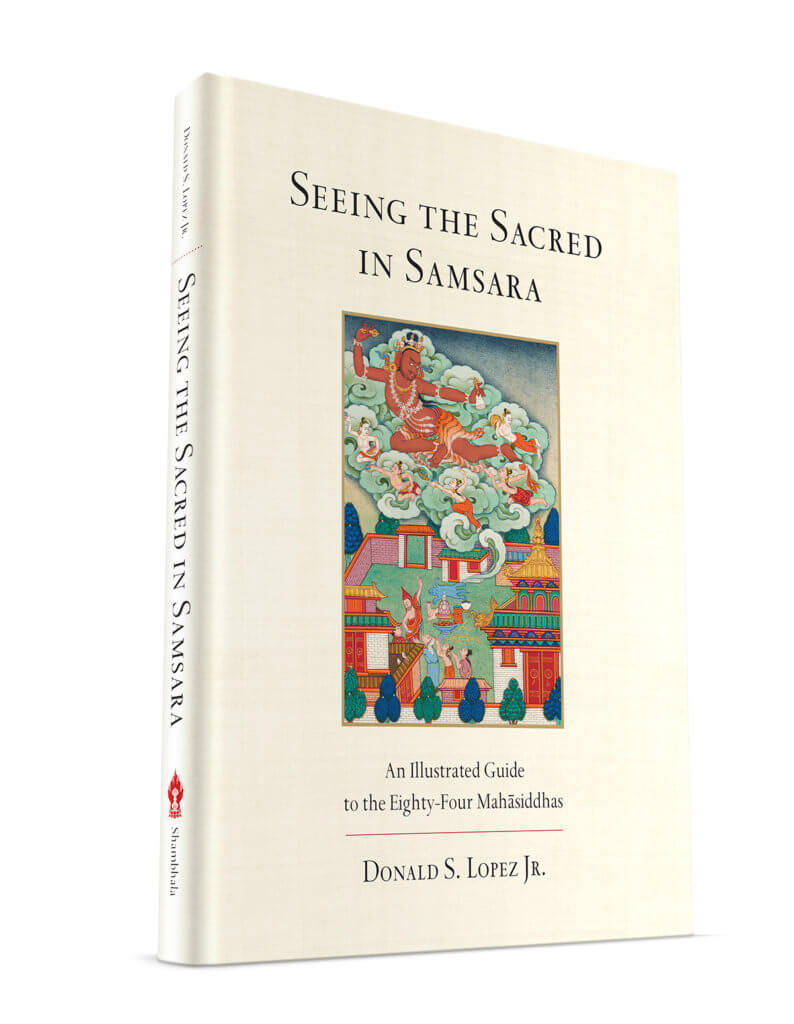

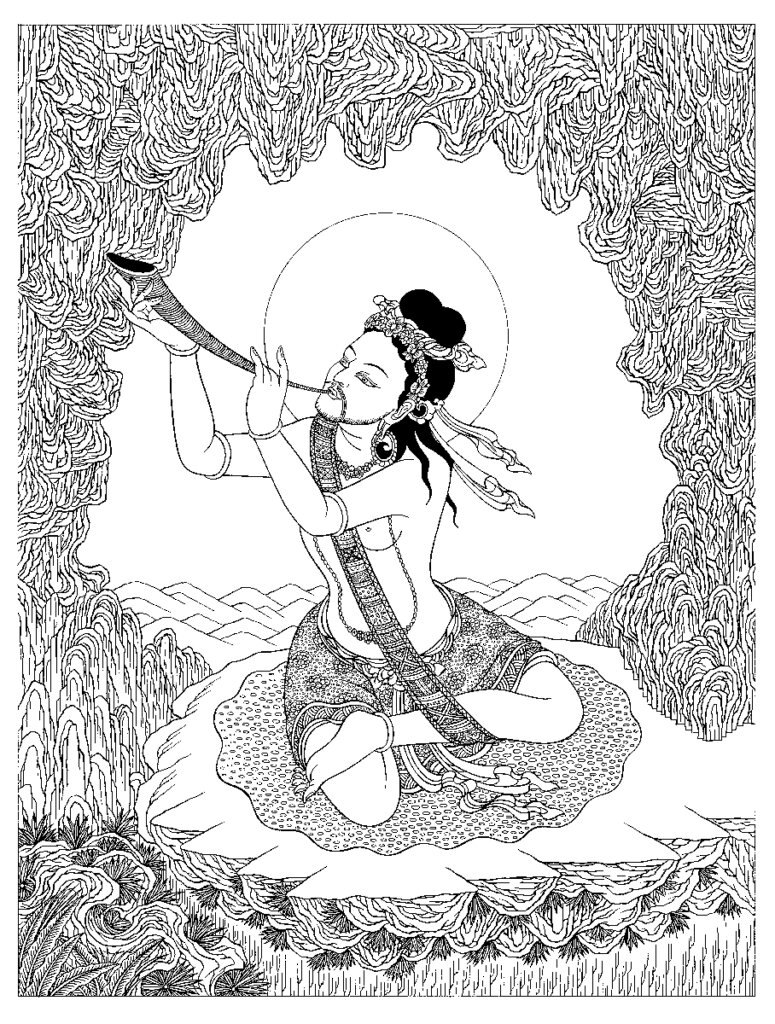

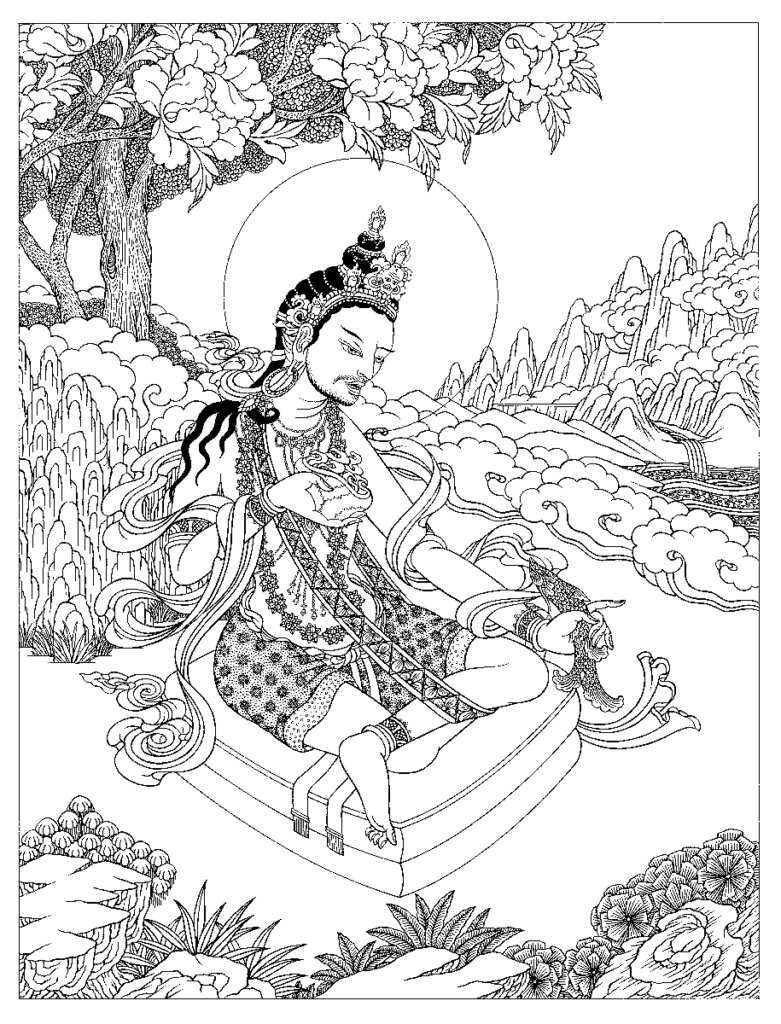

Seeing the Sacred in Samsara: An Illustrated Guide to the Eighty-Four Mahāsiddhas

By Donald S. Lopez Jr.

This exquisite full-color presentation of the lives of the eighty-four mahāsiddhas, or “great accomplished ones,” offers a fresh glimpse into the world of the famous tantric yogis of medieval India. The stories of these tantric saints have captured the imagination of Buddhists across Asia for nearly a millennium. Unlike monks and nuns who renounce the world, these saints sought the sacred in the midst of samsara. Some were simple peasants who meditated while doing manual labor. Others were kings and queens who traded the comfort and riches of the palace for the danger and transgression of the charnel ground. Still others were sinners—pimps, drunkards, gamblers, and hunters—who transformed their sins into sanctity.

This book includes striking depictions of each of the mahāsiddhas by a master Tibetan painter, whose work has been preserved in pristine condition. Published here for the first time in its entirety, this collection includes details of the painting elements along with the life stories of the tantric saints, making this one of the most comprehensive works available on the eighty-four mahāsiddhas.

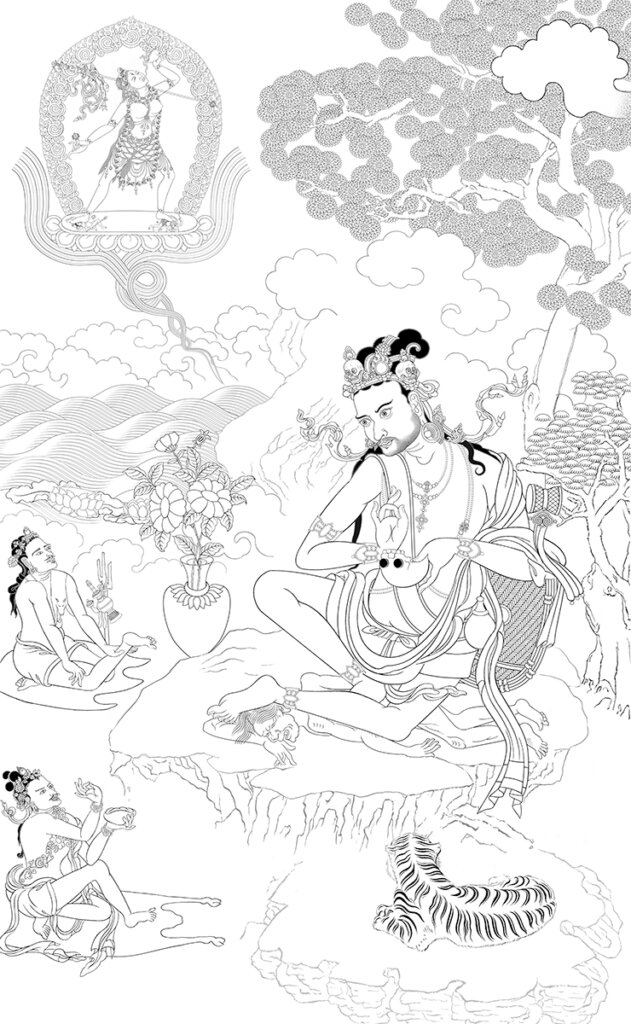

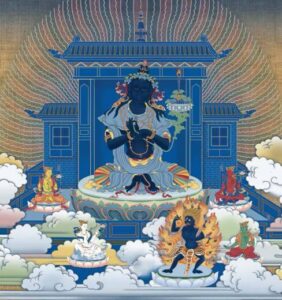

The Naropa image from this book is pictured at the top of this page and explains what is being depicted.

Additional Resources on Tilopa

Lotsawa House hosts at least one work by Naropa as well as several where he features.

Tilopa: A Guide for Readers to the Indian Mahasiddha

Tilopa: A Guide for Readers

The following short biography of Tilopa is from Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism:

Tilopa is born a brahman (member of the priestly caste) and, as a young man, renounces the world and takes monastic ordination, living in a monastery presided over by his uncle. After a short period, however, he has a vision of a dakini who gives him tantric initiation and instruction and sets him to meditating. She tells him, "Now speak like a madman and, after throwing off your monk’s robes, practice in secret.’’1 Then abruptly she disappears. Like other tantric practitioners, through abandoning the monastic life, appearing to be mad, and practicing in secret, Tilopa is enjoined to separate himself from conventional values and pursuits. In particular, by acting crazy, he puts himself in the category of outcaste, living beyond the pale of Hindu society, reviled and abused by others. All of this is to enable him to separate himself from the deceptive comforts and security of egoic existence within society. Tilopa follows the dakini’s instructions, wandering from place to place and meditating. Encountering obstacles, he seeks out and receives instruction from several gurus, all of them siddhas. Eventually, he is instructed to go to Bengal and to carry out his practice while pounding sesame seeds by day and acting as the servant of a prostitute by night. In these circumstances, defiling in the extreme for a brahman, he meditates, some sources say for twelve years. Having completed this phase of his practice, Tilopa realizes that he needs to withdraw completely from the provocations of ordinary life. He goes to Bengal and enters into retreat, in a tiny grass hut that he builds for himself. There, finally, he comes face-to-face with reality, in the person of the celestial buddha Vajradhara in the highest celestial realm. He later remarks, "I have no human guru. My guru is the Omniscient One. I have conversed directly with the Buddha."

Following his realization, Tilopa wanders about, bringing others onto the path and instructing them in the Vajrayana way. He becomes renowned as a powerful and unpredictable master, who in the service of the dharma, like other siddhas, often performs actions considered shocking or scandalous in a conventional setting. He spends much of his time in cremation grounds, practicing and teaching, as is common for the other siddhas. When debating with non-Buddhists, he often makes his points by means of miracles rather than discursive argument. Although Tilopa had several human teachers, his role as progenitor of the Kagyu¨ lineage stems from his having met the celestial buddha Vajradhara face-to-face and received teachings directly from him. Tilopa’s lineage includes teachings on mahamudra received directly from Vajradhara; practices of inner yoga that make up the ‘‘six yogas of Naropa’’; and anuttara-yoga tantra transmissions including father, mother, and nondual tantras.

Essential Texts by and about Tilopa

The Ganges Mahamudra Song of Realization

All lineages of Mahamudra meditation have their source in a verse teaching—a “song of realization”—sung by the Mahasiddha Tilopa to his disciple Naropa on the banks of the Ganges River more than a thousand years ago. In Sanskrit it is known as the Mahāmudropadeśa and in Tibetan: phyag rgya chen po’i man ngag. Since that time, the meaning of Tilopa’s instructions has been passed directly from master to disciple in a continuous stream that exists unbroken to this day.

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

Tilopa's Wisdom: His Life and Teachings on the Ganges Mahamudra

Most traditions of Mahamudra meditation can be traced back to the mahasiddha Tilopa and his Ganges Mahamudra, a “song of realization” that he sang to his disciple Naropa on the banks of the Ganges River more than a thousand years ago. In this book, Khenchen Thrangu, a beloved Mahamudra teacher, tells the extraordinary story of Tilopa’s life and explains its profound lessons. He follows this story with a limpid and practical verse-by-verse commentary on the Ganges Mahamudra, explaining its precious instructions for realizing Mahamudra, the nature of one’s mind. Throughout, Thrangu Rinpoche speaks plainly and directly to Westerners eager to receive the essence of Mahamudra instructions from an accomplished teacher.

Hardcover | Ebook

$34.95 - Hardcover

Tilopa's Mahamudra Upadesha: The Gangama Instructions with Commentary

By Sangyes Nyenpa Rinpoche, translated by David Molk

This book offers the reader a rare glimpse into the Mahamudra oral transmission, given in a traditional Tibetan context by one of the lineage’s most learned and accomplished contemporary masters.

Mahamudra meditation, while highly advanced, is yet simple, practical, and accessible for anyone, because what is identified and meditated upon is the very nature of one’s own mind. In Sangyes Nyenpa Rinpoche’s words, “The distinction between deception and liberation lies in whether we understand the ever-present nature of our own mind or not. Knowing our own face is liberation; not knowing our own face is samsara. This is not something far distant from us.”

The instructions are ideal for Westerners because the root text is manageable and Rinpoche has provided an outline of his own composition that makes it easily understandable. He explains terminology with frequent comparisons between Dzogchen and Mahamudra, quotes prolifically from scripture, gives clear examples, and generally cajoles, admonishes, and encourages his listeners to be true to their own spiritual path.

Books Featuring Tilopa

Paperback | Ebook

$22.95 - Paperback

The Great Kagyu Masters: The Golden Lineage Treasury

Compiled by Dorje Dze Öd, translated by Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche

The Golden Lineage Treasury was compiled by Dorje Dze Öd a great master of the Drikung lineage active in the Mount Kailasjh region of Western Tibet. This text of the Kagyu tradition profiles and the forefathers of the tradition including Vajradhara, the Buddha, Tilopa, Naropa, the Four Great Dharma Kings of Tibet, Marpa, Milarepa, Atisha, Gampopa, Phagmodrupa, Jigten Sumgon, and more.

The chapter on Tilopa is 22 pages long.

Hardcover | Ebook

$49.95 - Hardcover

Marpa Kagyu, Part One: Methods of Liberation: Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 7

The Treasury of Precious Instructions

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye

The seventh volume of this series, Marpa Kagyu, is the first of four volumes that present a selection of core instructions from the Marpa Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. This lineage is named for the eleventh-century Tibetan Marpa Chokyi Lodrö of Lhodrak who traveled to India to study the sutras and tantras with many scholar-siddhas, the foremost being Naropa and Maitripa. The first part of this volume contains source texts on mahamudra and the six dharmas by such famous masters as Saraha and Tilopa. The second part begins with a collection of sadhanas and abhisekas related to the Root Cakrasamvara Aural Transmissions, which are the means for maturing, or empowering, students. It is followed by the liberating instructions, first from the Rechung Aural Transmission. This section on instructions continues in the following three Marpa Kagyu volumes. Also included are lineage charts and detailed notes by translator Elizabeth M. Callahan.

There are the following works by Tilopa included:

- Ganges Mahāmudrā: Esoteric Instructions on Mahāmudrā

- Truly Valid Words: The Esoteric Instructions of the Ḍākinī

- Esoteric Instructions on the Six Dharmas

- The Short Text: The Wish-Fulfilling Gems of the Glorious Cakrasaṃvara Aural Transmission from the Tradition of Jetsun Rechungpa

Paperback | Ebook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Rain of Wisdom: The Essence of the Ocean of True Meaning

Translated by Nalanda Translation Committee under the guidance of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

The art of composing spontaneous songs that express spiritual understanding has existed in Tibet for centuries. Over a hundred of these profound songs are found in this collection of the works of the great teachers of the Kagyü lineage, known as the Practice Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism.

The chapter on Tilopa details his experiences with his teacher Matangi, receiving the abhisheka for Guhyasamaja, the prostitute Darima, and the famous doha on sesame oil. As Trungpa Rinpoche explains in the foreword of the book, "the songs of Tilopa point out the indivisibility of sarpsara and nirvana so that whatever arises is neither rejected nor accepted and we can recognize naked and raw coemergent wisdom on the spot."

The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa

Edited by Glenn Mullin

This book on the Six Yogas contains important texts on this esoteric doctrine, including original Indian works by Tilopa and Naropa and writings by great Tibetan lamas. It contains an important practice manual on the Six Yogas as well as other works that discuss the practices, their context, and the historical continuity of this most important tradition.

- The Oral Instruction of the Six Yogas by Tilopa

- Vajra Verses of the Whispered Tradition by Naropa

- Notes on "A Book of Three Inspirations" by Je Sherab Gyatso

- Handprints of the Profound Path of the Six Yogas of Naropa by Gyalwa Wensapa

- A Practice Manual on the Six Yogas of Naropa by Tsongkhapa

- The Golden Key: A Profound Guide to the Six Yogas of Naropa by the First Panchen Lama

Hardcover | Ebook

$24.95 - Hardcover

The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra: Teachings, Poems, and Songs of the Drukpa Kagyu Lineage

Translated by Gerardo Abboud, Sean Price, and Adam Kane

The Drukpa Kagyu lineage is renowned among the traditions of Vajrayana Buddhism for producing some of the greatest yogis from across the Himalayas. After spending many years in mountain retreats, these meditation masters displayed miraculous signs of spiritual accomplishment that have inspired generations of Buddhist practitioners. The teachings found here are sources of inspiration for any student wishing to genuinely connect with this tradition.

These translations include Mahamudra advice and songs of realization from major Tibetan Buddhist figures such as Gampopa, Tsangpa Gyare, Drukpa Kunleg, and Pema Karpo, as well as modern Drukpa masters such as Togden Shakya Shri and Adeu Rinpoche. This collection of direct pith instructions and meditation advice also includes an overview of the tradition by Tsoknyi Rinpoche.

The first chapter, on Tilopa, is another beautiful translation of the Ganges Mahamudra.

Combined with guidance from a qualified teacher, these teachings offer techniques for resting in the naturally pure and luminous state of our minds. As these masters make clear, through stabilizing the meditative experiences of bliss, clarity, and nonthought, we will be liberated from suffering in this very life and will therefore be able to benefit countless beings.

Translator on Gerardo Abboud on The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra

Hardcover | Ebook

$29.95 - Hardcover

Seeing the Sacred in Samsara: An Illustrated Guide to the Eighty-Four Mahāsiddhas

By Donald S. Lopez Jr.

This exquisite full-color presentation of the lives of the eighty-four mahāsiddhas, or “great accomplished ones,” offers a fresh glimpse into the world of the famous tantric yogis of medieval India. The stories of these tantric saints have captured the imagination of Buddhists across Asia for nearly a millennium. Unlike monks and nuns who renounce the world, these saints sought the sacred in the midst of samsara. Some were simple peasants who meditated while doing manual labor. Others were kings and queens who traded the comfort and riches of the palace for the danger and transgression of the charnel ground. Still others were sinners—pimps, drunkards, gamblers, and hunters—who transformed their sins into sanctity.

This book includes striking depictions of each of the mahāsiddhas by a master Tibetan painter, whose work has been preserved in pristine condition. Published here for the first time in its entirety, this collection includes details of the painting elements along with the life stories of the tantric saints, making this one of the most comprehensive works available on the eighty-four mahāsiddhas.

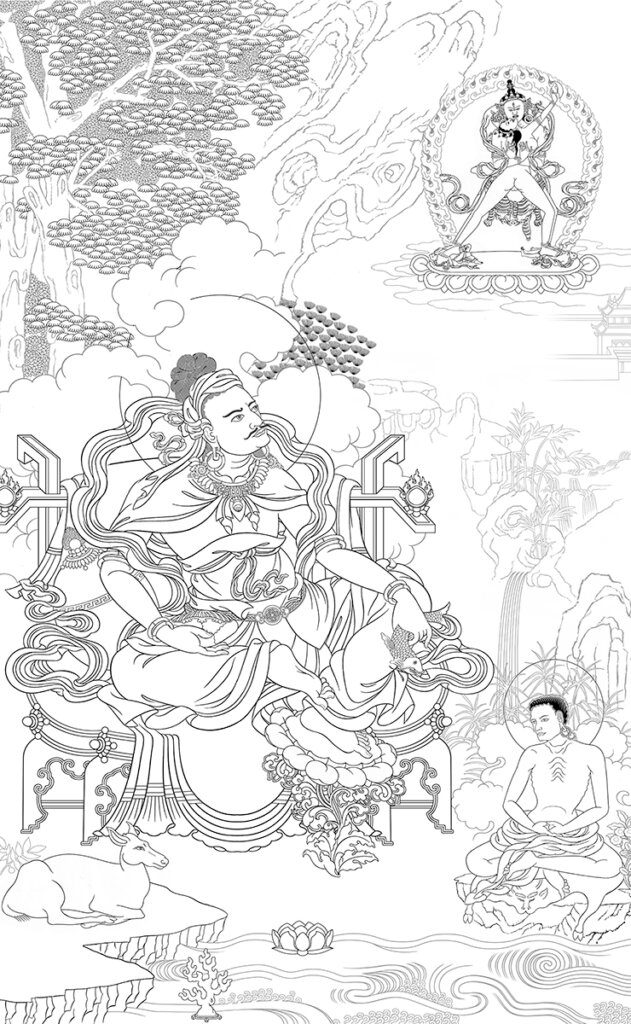

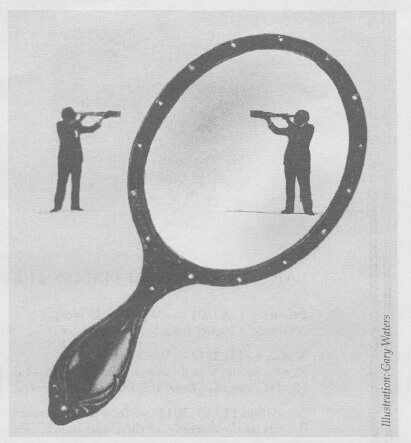

The Tilopa image from this book is pictured at the top of this page and tells the story of what is being depicted.

Additional Resources on Tilopa

Lotsawa House hosts at least one work by Tilopa

Remembering Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

It is with great heartache that we share that Ven. Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche, a prominent teacher of the Karma Kagyu School, has passed at the age of 91 on June 4, 2023. We'd like to take a moment to appreciate this remarkable master and prolific author. We are happy to have published over a dozen books by Thrangu Rinpoche over the years, and we are grateful to be a part of the incredible impact Rinpoche has made on the world.

On June 8th Thrangu Monastery issued the following address:

“…On June 4, the full moon day of the fourth Tibetan month, Saga Dawa—the sacred anniversary of the Buddha Shakyamuni, our incomparably kind teacher, passing into parinirvana—Rinpoche decided that he had completed his activity for this life… The Gyalwang Karmapa instructed that, as Rinpoche needed to be in a peaceful environment, this news should not be announced for four days. This is the reason why no announcement has been made until now.”

A Short Biography of Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche from the Preface to An Ocean of Ultimate Meaning

Khenchen Thrangu, the ninth Thrangu Rinpoche, whose personal name is Karma Lodrö Ringluk Marwe Sengge, was born in the region of Gawa in the east of the Tibetan plateau in 1933. At about the age of four he was recognized as the rebirth of the eighth Thrangu, Karma Tendzin Trinle Namgyal, by the twelve-year-old sixteenth Karmapa, Rigpe Dorje, and the eleventh Taisitupa, Pema Wangchuk Gyalpo.

From an early age, Thrangu Rinpoche showed great aptitude in scholarship, studying at the Thrangu monastic college under Khenpo Lodrö Rabsal from 1948 to 1953. In the late fifties, the Communist suppression of Tibetan monasteries caused him to flee to India in a large group of refugees. Surviving an intense military attack, he reached India via Bhutan in 1959. After demonstrating his scholarship by obtaining the scholastic degree of Geshe Rabjam at an examination in West Bengal—the highest degree awarded within the Gelugpa

tradition of the Dalai Lama, which emphasizes scholastic studies—in 1968 Thrangu Rinpoche became the khenpo (professor) of the new Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim, India, and the tutor for the principal tulkus of the Karma Kagyu tradition.

Since the late 1970s, Thrangu Rinpoche has traveled extensively, spending most of each year teaching at centers in the Far East and the West.

Books by Thrangu Rinpoche

As one of the foremost teachers in the Karma Kagyu tradition, Thrangu Rinpoche wrote several books and commentaries on the Mahamudra tradition including Tilopa's Wisdom, An Ocean of the Ultimate Meaning, and more.

Reader's Guides and Articles on Thrangu Rinpoche

Learn More about Khenchen Thrangu's Life and Legacy at https://rinpoche.com/

Doha and Gur: Indian and Tibetan Songs of Realization

Doha and Gur: Indian and Tibetan Songs of Realization

Doha and Gur

Doha (Sanskrit) or Nam Gur (Tibetan, Gur for short), is often translated as "Songs of Realization." This form of poetry is often sung or recited spontaneously and is characteristic of Vajrayana Buddhism. Dohas are often used as a means of transmitting wisdom and spiritual aphorisms, but also function as songs of praise and enjoyment especially in the context of ganachakra (tantric feast).

There are various forms of Doha with themes ranging from bliss and rapture to admonishing samsaric lifestyles to praising the lives of great masters. While a great number of Doha from both the Indian and Tibetan tradition are attributed to the Kagyu and Mahamudra tradition (as we'll see below), with the great sage, Milarepa, being the most widely known, Doha are found in all schools of Vajrayana Buddhism.

Our selection of books on Doha range from academic research-based explorations of the poetic genre to translations of traditional texts as well as biographical accounts of several famous Buddhist masters and writers of doha from our Lives of the Masters (LOM) series. Continue reading below or jump to a section of interest to explore this topic.

Songs of Realization in Mahamudra and the Kagyu Tradition

Tilo, Naro, Marpa, Mila: Doha and the Masters of Mahamudra

The Kagyu, or "Oral Lineage," school is one of the main schools of Tibetan Buddhism and can be traced back to the 10th India. There are several lines of lineage including the Shangpa Kagyu which traces it's lineage from the two dakini's Niguma and Sukhasiddhi as well as the Karma Kagyu, Drikung Kagyu, and Taklung Kagyu. The principle Kagyu lineage found today stems from the the spiritual lineage of Gampopa, which can be traced back to Tilopa, the 10th century Indian Mahasiddha.

Regarding Songs of Realization, or Doha, the Kagyu lineage is well known for transmitting spiritual teachings through these spontaneous songs. Among the masters of the Kagyu Mahamudra lineage, Milarepa is best known for his remarkable devotion and willingness to tread along the spiritual path despite difficult circumstances in addition to his style of teaching in spontaneous verse or doha. In fact, versified expressions of wisdom and pith instruction is common among Kagyu masters and is reflective of the spiritual prowess associated with Mahasiddhas (Great Spiritual Adepts) whose spiritual abilities gain them immediate access to the nature of reality and an ability to express wisdom teachings spontaneously and oftentimes outside of conventional means (for example, through song and dance).

The following books stem from the Kagyu tradition connected to Milarepa beginning with Tilopa (10th century) followed by his disciple Naropa (cira 1016–1100 CE), followed by Marpa (1012–1097), and finally, Milarepa (circa 1040-1123). Additional sources from other Kagyu linages are included below.

Tilopa's Wisdom: His Life and Teachings on the Ganges Mahamudra

Most traditions of Mahamudra meditation can be traced back to the mahasiddha Tilopa and his Ganges Mahamudra, a “song of realization” that he sang to his disciple Naropa on the banks of the Ganges River more than a thousand years ago. In this book, Khenchen Thrangu, a beloved Mahamudra teacher, tells the extraordinary story of Tilopa’s life and explains its profound lessons. He follows this story with a limpid and practical verse-by-verse commentary on the Ganges Mahamudra, explaining its precious instructions for realizing Mahamudra, the nature of one’s mind. Throughout, Thrangu Rinpoche speaks plainly and directly to Westerners eager to receive the essence of Mahamudra instructions from an accomplished teacher.

Naropa's Wisdom: His Life and Teachings on Mahamudra

As the disciple of Tilopa and the guru of Marpa the Translator, Naropa is one of the accomplished lineage holders of the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. He expressed his realization in the form of spiritual songs, pithy yet beautiful poems that he sung spontaneously. In this book, Khenchen Thrangu, a contemporary Karma Kagyu master, first tells the story of Naropa’s life and explains the lessons we can learn from it and then provides verse-by-verse commentary on two of his songs. Both songs contain precious instructions on Mahamudra, the direct experience of the nature of one's mind, which in this tradition is the primary means to realize ultimate reality and thus attain buddhahood. Read More

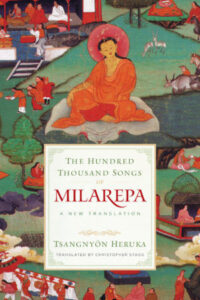

The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa: A New Translation

Translated by Christopher Stagg

By Tsangnyon Heruka

By Milarepa

Powerful and deeply inspiring, there is no book more beloved by Tibetans than The Hundred Thousand Songs, and no figure more revered than Milarepa, the great eleventh-century poet and saint. An ordinary man who, through sheer force of effort, faith, and perseverance, overcame nearly insurmountable obstacles on the spiritual path to achieve enlightenment in a single lifetime, he stands as an exemplar of what it is to lead a spiritual life. Read More

Milarepa: Lessons from the Life and Songs of Tibet's Great Yogi

By Chogyam Trungpa

Edited by Judith L. Lief

He went from being the worst kind of malevolent sorcerer to a devoted and ascetic Buddhist practitioner to a completely enlightened being all in a single lifetime. The story of Milarepa (1040–1123) is a tale of such extreme and powerful transformation that it might be thought not to have much direct application to our own less dramatic lives—but Chögyam Trungpa shows otherwise. This collection of his teachings on the life and songs of the great Tibetan Buddhist poet-saint reveals how Milarepa’s difficulties can be a source of guidance and inspiration for anyone. His struggles, his awakening, and the teachings from his remarkable songs provide precious wisdom for all us practitioners and show what devoted and diligent practice can achieve.

Opening the Treasure of the Profound: Teachings on the Songs of Jigten Sumgon and Milarepa

By Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche

By Milarepa

By Jigten Sumgon

Spiritual teachings in the form of songs—spontaneous expressions of deep wisdom and understanding that reveal the nature of reality—have been treasured since the dawn of Buddhism in India. In Opening the Treasure of the Profound, Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen translates nine such songs, by Milarepa and Jigten Sumgön, and then explains them in contemporary terms. His insights take the Buddha’s ancient wisdom out of the realm of the intellectual and directly into our hearts. Here, we are invited into the world of transmission from master to disciple in order to discover truth for ourselves—to open the treasure of profound wisdom that fully realizes the nature of reality.

Collected Works

The Rain of Wisdom: The Essence of the Ocean of True Meaning

Translated by Nalanda Translation Committee

The art of composing spontaneous songs that express spiritual understanding has existed in Tibet for centuries. Over a hundred of these profound songs are found in this collection of the works of the great teachers of the Kagyü lineage, known as the Practice Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism.

Many readers are already familiar with the colorful life of the yogin Milarepa, an early figure in the Kagyü lineage, some of whose songs are included here. Songs by over thirty other Buddhist teachers are also presented, from those of Tilopa, the father of the lineage, to those of the Sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa, as well as several songs by Chögyam Trungpa, the noted teacher of Buddhism in America who directed the translation of The Rain of Wisdom.

The diversity of the songs mirrors the richness of Tibetan Buddhism and gives us clear portraits of some of its most eminent teachers. Their longing for truth, their heartfelt devotion, and their sense of humor are all reflected. These poems share a beauty and intensity that have made them famous in Tibetan literature. With its vivid imagery and deep insight, The Rain of Wisdom communicates a profound and timeless understanding.

The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra: Teachings, Poems, and Songs of the Drukpa Kagyu Lineage

Translated by Sean Price

Translated by Adam Kane

Translated by Gerardo Abboud

Foreword by Tsoknyi Rinpoche

The Drukpa Kagyu lineage is renowned among the traditions of Vajrayana Buddhism for producing some of the greatest yogis from across the Himalayas. After spending many years in mountain retreats, these meditation masters displayed miraculous signs of spiritual accomplishment that have inspired generations of Buddhist practitioners. The teachings found here are sources of inspiration for any student wishing to genuinely connect with this tradition.

These translations include Mahamudra advice and songs of realization from major Tibetan Buddhist figures such as Gampopa, Tsangpa Gyare, Drukpa Kunleg, and Pema Karpo, as well as modern Drukpa masters such as Togden Shakya Shri and Adeu Rinpoche. This collection of direct pith instructions and meditation advice also includes an overview of the tradition by Tsoknyi Rinpoche.

Songs of Spiritual Experience: Tibetan Buddhist Poems of Insight and Awakening

Translated by Jas Elsner

Translated by Thupten Jinpa

Foreword by H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

The first major anthology of Tibetan spiritual poetry available in the West, Songs of Spiritual Experience offers original translations of fifty-two poems from all the traditions and schools of Tibetan Buddhism, spanning the eleventh to the twentieth centuries. These poems communicate spiritual insight with grace and precision, addressing the themes of impermanence, solitude, guru devotion, emptiness, mystic consciousness, and the path of awakening. Also included here is a thorough introduction exploring the characteristics of Tibetan verse and its role in Buddhism, and a glossary containing notes on the poems.

Marpa Kagyu, Vol. 1: Methods of Liberation

Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 7 (The Treasury of Precious Instructions)

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Elizabeth M. Callahan

Although not specifically a book on doha, Marpa Kagyu, Volume 1 includes select texts from the Mahasiddha Saraha called Treasury of Dohās: Esoteric Instructions on Mahāmudrā and Doha for the People: Song That Is a Treasury of Dohās. Saraha, also known as Sarahapa or Sarahapdāda, was an 8th century Indian master and is known as the first Mahasiddha as well as one of the first founds of the Mahāmudrā tradition.

More about this volume:

The seventh volume of the series, Marpa Kagyu, is the first of four volumes that present a selection of core instructions from the Marpa Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. This lineage is named for the eleventh-century Tibetan Marpa Chokyi Lodrö of Lhodrak who traveled to India to study the sutras and tantras with many scholar-siddhas, the foremost being Naropa and Maitripa. The first part of this volume contains source texts on mahamudra and the six dharmas by such famous masters as Saraha and Tilopa. The second part begins with a collection of sadhanas and abhisekas related to the Root Cakrasamvara Aural Transmissions, which are the means for maturing, or empowering, students. It is followed by the liberating instructions, first from the Rechung Aural Transmission. This section on instructions continues in the following three Marpa Kagyu volumes. Also included are lineage charts and detailed notes by translator Elizabeth M. Callahan. Read More

Timeless Rapture: Inspired Verse of the Shangpa Masters

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Edited and translated by Ngawang Zangpo

Throughout history awakened ones have celebrated the rapture of mystical states with inspired verse sung extemporaneously. This book offers a rare glimpse into the mysticism of the Shangpa Kagyu lineage a tradition based mainly on the profound teaching of two women. This compendium of spontaneous verse sung by tantric Buddhist masters from the tenth century to the present includes translations as well as short descriptions of each poet's life and a historical overview of the lineage.

From the Sakya Lineage

Treasures of the Sakya Lineage: Teachings from the Masters

By Migmar Tseten

Foreword by H.H. Sakya Trizin

Though not specifically a book on Doha, Treasures of the Sakya Linage includes several Doha including The Great Song of Experience by Jetsun Dragpa Gyaltsten

More about this book:

Treasures of the Sakya Lineage is a rich collection of teachings by both contemporary and ancient Sakya masters, showing a thousand years of lineage continuity. It provides an overview of the history, view, key lineage figures, and crucial teachings of the oldest continuously operating institution among the four lineages of Tibetan Buddhism. Learn More

From the Lives of the Masters Series

Our Lives of the Masters Series (LOM) provide a much needed glimpse into the lives of some of the most creative thinkers in history. Each volume, as Kurtis Schaeffer, the series editor puts it, "tells the story of an innovator who embodied the ideals of Buddhism, crafted a dynamic living tradition during his or her lifetime, and bequeathed a vibrant legacy of knowledge and practice to future generations."

In terms of Songs of Realization, though not explicitly focused on Doha the following volumes from LOM include select translations of Dohas from three notable Indian and Tibetan masters.

Maitripa: India's Yogi of Nondual Bliss

Maitripa was a student of Naropa and prominent Indian Buddhist Mahasiddha known for his remarkable teachings on emptiness and non-duality. He composed numerous treatise in addition to a great number of Dohas. Maitripa includes A Treasure of Dohās and other verses such as The Ten Verses on True Reality.

More about this volume:

Maitripa (986–1063) is one of the greatest and most influential Indian yogis of Vajrayana Buddhism. The legacy of his thought and meditation instructions have had a profound impact on Buddhism in India and Tibet, and several important contemporary practice lineages continue to rely on his teachings.

Early in his life, Maitripa gained renown as a monk and scholar, but it was only after he left his monastery and wandered throughout India as a yogi that he had a direct experience of nonconceptual realization. Once Maitripa awakened to this nondual nature of reality, he was able to harmonize the scholastic teachings of Buddhist philosophy with esoteric meditation instructions. This is reflected in his writings that are renowned for evoking a meditative state in those who have trained appropriately. He eventually became the teacher of many well-known accomplished masters, including Padampa Sangyé and the translator Marpa, who brought his teachings to Tibet. Read More

The Second Karmapa Karma Pakshi: Tibetan Mahasiddha

Karma Pakshi was recognized as a as a reincarnation of the First Karmapa, Dusum Khyenpa at a young age and underwent extensive studies and practice. He authored several texts some of which have survived and is known for his systemization of the Kathok tradition. The Second Karmapa Karma Pakshi includes a number of his musings and reflections including Song for a Disciple and Deathbed Song.

More about this volume:

Karma Pakshi is considered influential in the development of the reincarnate lama tradition, a system that led to the lineage of the Dalai Lamas. Born in East Tibet in the thirteenth century, Karma Pakshi himself was the first master to be named Karmapa, a lineage that continues to modern times and has millions of admirers worldwide. During his lifetime, Karma Pakshi was widely acknowledged as a mahāsiddha—a great spiritual adept—and was therefore invited to the Mongol court at the apogee of its influence in Asia. He gave spiritual advice and meditation instructions to the emperor Möngke Khan, whom he advised to engage in social policies, to release prisoners, and to adopt a vegetarian diet. After Möngke’s death, Karma Pakshi was imprisoned by the successive emperor Kubilai Khan, and much of Karma Pakshi’s writing was done while he was captive in northeast China. He was eventually released and returned to Tibet, where he commissioned one of the medieval world’s largest metal statues: a seated Buddha sixty feet high.

Centuries later, two Buddhist meditation masters, the First Mingyur Rinpoche and Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, were inspired by Karma Pakshi to write meditation practices that are profoundly important to contemporary Tibetan Buddhist practitioners: respectively, the Karma Pakshi Guru Yoga and the Sādhana of Mahāmudrā. Read More

Gendun Chopel: Tibet's Modern Visionary

Gendun Chopel was a great scholar, poet, and artist known for his creative and unconventional thinking. Gendun Chopel includes a selection of poetry in addition to his writing about India and Tibet and his more controversial teachings from his Treatise on Passion.

More about this volume:

Visionary, artist, poet, iconoclast, philosopher, adventurer, master of the arts of love, tantric yogin, Buddhist saint. These are some of the terms that describe Tibet’s modern culture hero Gendun Chopel (1903–1951). The life and writings of this sage of the Himalayas mark a key turning point in Tibetan history, when twentieth-century modernity came crashing into Tibet from British India to the south and from Communist China to the east. For the first time, the astonishing breadth of his remarkable accomplishments is captured in a single, definitive volume.

Here is an exploration of Gendun Chopel’s life as a recognized tulku, or incarnation of a previous master, from becoming a monk and soon surpassing the knowledge of his teachers, to his travels and discoveries throughout Tibet, India, and Sri Lanka. His exposure to the wider world brought together his philosophical training, artistic virtuosity, and meditative experience, inspiring an incredible corpus of poetry, prose, and painting. While Gendun Chopel was known by the Tibetan establishment for his vast learning and progressive ideas—which eventually landed him in a Lhasa prison—he was little appreciated in his lifetime. But since his death in 1951, his legacy, fame, and relevance across the Tibetan cultural landscape and beyond have continued to grow. Read More

Modern Visionaries

The tradition of spontaneous instruction and Songs of Realization continues today through modern visionaries. Likewise, Tibetan poetry continues to gain interest among readers and practitioner alike as translations of these meaningful texts become available. The following are just a couple examples of modern Tibetan Buddhist songs and poetry.

Timely Rain: Selected Poetry of Chogyam Trungpa

By Chogyam Trungpa

Edited by David I. Rome

Foreword by Allen Ginsberg

Newly selected poetry from previously published and unpublished works, Timely Rain is the definitive edition of poems and sacred songs of the renowned Tibetan meditation master, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

First Thought Best Thought: 108 Poems

By Chogyam Trungpa

Introduction by Allen Ginsberg

Here is a unique contribution to the field of poetry: a new collection of works by America's foremost Buddhist meditation master, Chögyam Trungpa. These poems and songs—most of which were written since his arrival in the United States in 1970—combine a background in classical Tibetan poetry with Trungpa's intuitive insight into the spirit of America, a spirit that is powerfully evoked in his use of colloquial metaphor and contemporary imagery. Read More

Research on Tibetan Literature

Lastly, we are delighted to present this collection of essays edited by Jose Cabezon and Roger R. Jackson which exemplifies the great many styles of Tibetan Buddhist Literature including Doha and Gur.

Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre

Edited by Jose Cabezon

Edited by Roger R. Jackson

Tibetan Literature addresses the immense variety of Tibet's literary heritage. An introductory essay by the editors attempts to assess the overall nature of 'literature' in Tibet and to understand some of the ways in which it may be analyzed into genres. The remainder of the book contains articles by nearly thirty scholars from America, Europe, and Asia—each of whom addresses an important genre of Tibetan literature. These articles are distributed among eight major rubrics: two on history and biography, six on canonical and quasi-canonical texts, four on philosophical literature, four on literature on the paths, four on ritual, four on literary arts, four on non-literary arts and sciences, and two on guidebooks and reference works.

Related Books on Buddhist Poetry

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

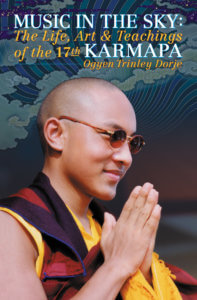

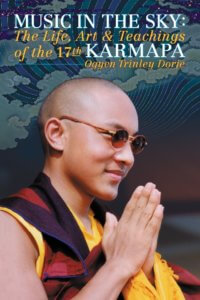

Excerpts on Life of the 17th Karmapa

| The following article is from the Spring, 2003 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Ogyen Trinley Dorje

The first authorized compilation of the Karmapa's teachings, plus stories from his life and examples of his art

As the second millennium drew to a close, the Seventeenth Karmapa leapt from the roof at his monastery in Tibet. Evading his Chinese guards, the then 14-year-old spiritual leader began a grueling, dangerous journey to India. The Karmapa's picture has appeared all over the world since then, yet his own words are hard to find. Now, for the first time in print, Music in the Sky offers a series of the Karmapa's profound teachings, an extensive selection of his poetry, and a detailed and gripping account of his life and flight from his homeland. Readers will be captivated by this wonderfully accessible and profound book.

Music in the Sky concludes with brief biographies of all 16 previous Karmapas, specially composed for this publication by the highly respected Seventh Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche. Here, the reader will discover the compelling histories of the first Tibetan masters to be recognized as reincarnate lamas. Music in the Sky presents a definitive portrait of the Seventeenth Karmapa, strengthened and illuminated by an authoritative depiction of his place in one of the world's most revered lines of spiritual teachers.

The bright sun of the Gyalwa Karmapa shines throughout this book. It illuminates his young life from his discovery in eastern Tibet through his difficult journey to India. The text also reveals the breadth of his teachings and the beauty of his poetry and art.

Anyone wishing to know more about him and the ancient tradition of Buddhism he embodies would do well to read this book.

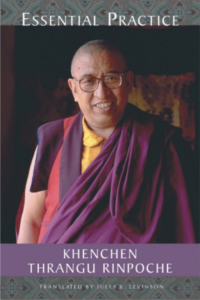

KHENCHEN THRANGU RINPOCHE, tutor to H.H. the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa, and author of Essential Practice, Everyday Consciousness and Buddha- Awakening

(now titled, Everyday Consciousness and Primordial Awareness).

MICHELE MARTIN has published numerous translations and has served as an oral translator from Tibetan and as a teacher all over the world. She lives in Woodstock, NY.

The following is a selection of excerpts from Music in the Sky.

The biography:

Arriving at the monastery around 9: 00 A.M., Lama Tsultrim took out the carefully wrapped clothes they had bought for the Karmapa and told one of his attendants,

"These are Lama Nyima's. Please bring them to him."

In this way, the Karmapa's change of clothes arrived safely in his room.

Then Lama Tsultrim went to talk to the administration about leaving. In line with his former paving project, he said,

"We need a courtyard in front of the new temple of the Tsurphu Lhachen. I want to go and raise funds for it in Nagchu."

While practicing the path that leads to stable, unexcelled bliss, when we meet with problems, we are also meeting with the pure nature they embody: the possibility of liberation arises at the same time as the problem.

He was easily given permission to leave and returned to his room, where he lived alone. He was too worried to eat. Thinking that he was leaving on a long trip, his friends came to visit with him. They offered to take his things to the car, but he replied,

"I'm not sure if I'm leaving tonight or tomorrow morning, so let's wait on that."

Bidding good-bye and good luck, they left.

This same day, Lama Nyirna telephoned from Tsurphu to Nenang Lama in Lhasa. In the course of their conversation, he mentioned:

"This evening at 10:30 the Chinese are showing a special program on TV. Why don't you take a look at it?"

Nenang Lama responded,

"I'd like to see it."

This way he knew that the guards would be watching TV at 10:30 and the Karmapa could escape then.

I have many relatives and friends in Tibet, but one day I will die and have to part from each one of them. His Holiness is a great master of Tibet and has been for so many generations. My broader responsibility is to him.

That afternoon, Lama Nyima and Thubten said to the driver, Dargye,

"Bring around the car and let's go for a little drive."

They went to the Lower Park, a beautiful place with a summer residence for the Karmapa and the home of a special deer. They left the car on the road and walked up into the park. They said to Dargye,

"Let's sit down here. Have a seat, we had a special purpose in inviting you here. His Holiness is leaving for India and thought that you would be the best person to drive. You're an experienced driver and know the car so well. If you don't want to go, that's all right. We're not forcing you in any way. Everything depends on your mind and inclination. Can you make up your mind to leave your parents and relatives? Think it over carefully. If you decide to go, we leave tonight at 10:30. If you come, it's a great decision. If you choose not to go, it's all right, but you must not tell anyone else."

Dargye reflected:

"I have many relatives and friends in Tibet, but one day I will die and have to part from each one of them. His Holiness is a great master of Tibet and has been for so many generations. My broader responsibility is to him."

He replied:

"I will go with you. Don't worry."

Around five o'clock that afternoon, Lama Nyima came to visit Lama Tsultrim in his room to confirm that they would be leaving at 10:30. He gave him a necklace of coral and zi stones for the Karmapa saying,

"When he arrives at Rumtek, it would be beneficial to wear it during lama dancing."

He advised Lama Tsultrim to be extremely careful on the road, taking good care of the Karmapa so that the police would not capture him and they could arrive safely in India. He said,

"If His Holiness can escape to India and meet Situ Rinpoche, Gyaltsap Rinpoche, and Jamgon Rinpoche and finally go to Rumtek, I will have no regrets even if I lose my life."

then at the end of the Mahakala puja, I realized he had composed a recognition letter for a young tulku.

During this uncertain year, the Karmapa continued to recognize tulkus. Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche described one occasion:

"One evening, we were doing the Mahakala puja, and His Holiness the Karmapa asked me to bring the computer. I was very uncomfortable bringing the computer to the Mahakala puja, but it was a command, so I brought his laptop to the puja. Then he said to write down what he would dictate, and so in between the chanting, I was writing his words down. He would say one word and then play the music with the damaru and bell, and then he would say another word. At first, I could not tell what he was dictating, and then at the end of the Mahakala puja, I realized he had composed a recognition letter for a young tulku. It just comes like that. There is the name of a place, the father's name, the mother's name, and the year in which the -child is born. Amazing! I have heard of these things before but never experienced them directly."

Spiritual traditions have their freedom, and we are also free to choose one that draws us and to hold its lineage. With many different traditions, the Buddhist teachings have a broader opportunity to grow and spread and bring benefit to this world.

From the teachings:

Question: Do we need to embrace just one spiritual tradition, or can we go around to all of them and take a little here and a little there?

Answer: All over the world, we find many diverse spiritual traditions. Within Tibet, there are mainly five that have classic descriptions: the glorious Sakyapa, the Nyingma of the Secret Mantrayana, the Gelukpa or those from the mountain of Ganden, the Kagyupa, protectors of living beings, and the Bonpo of the unchanging, nature. Each one of these accords with the particular perspectives of its followers. In the realm of taste, if someone likes bread, then they are given bread; if they like tea, they are given tea. In the same way, when we are studying, whichever teaching draws our interest and devotion is the one we study and practice.

The Buddha taught for the benefit and happiness of every living being, not to force people to practice a particular spiritual tradition. For example, someone might prefer the yellow hat of the Gelukpa tradition to the red hat of the Kagyu. People should follow what they want to do, and later the reason for their preference, perhaps a hidden feeling, will surface. Therefore, from the perspective of what appears and appeals to individual beings, the different spiritual traditions were taught.

This spiritual tradition called Buddhism was taught by Shakyamuni Buddha so that all beings would benefit and attain happiness. There was absolutely no pressure to coerce anyone into practicing this tradition. As with the chillies, forceful tactics do not help at all. The Buddha did not teach to bring discomfort; he taught so that every living being could gather all the enrichments of life that bring well-being and happiness. Especially in this present world, independence, peace, and happiness are important. Spiritual traditions have their freedom, and we are also free to choose one that draws us and to hold its lineage. With many different traditions, the Buddhist teachings have a broader opportunity to grow and spread and bring benefit to this world.

While practicing the path that leads to stable, unexcelled bliss, when we meet with problems, we are also meeting with the pure nature they embody: the possibility of liberation arises at the same time as the problem. We should also remember that we are practicing not just for our own benefit but for the benefit of the infinite living beings in all realms.

For those who are practicing Dharma, various negative conditions come about and different kinds of fear arise. These can cause doubts to surface:

"Why should this be happening?"

Such thoughts could even propel someone into abandoning the Dharma. We should remember, however, that these negative situations arise for everyone who practices the Dharma, whether they are part of the monastic sangha or lay people who have taken refuge in the Three jewels.

The Dharma is of great value: it is an unexcelled path that brings us and all living beings equal to the extent of space onto the path of bodhichitta that leads to complete liberation. Since we are seeking to attain such a great goal, naturally there will be problems. Further, not only in relation to our Dharma practice but whatever activity we may be engaged in, it is not possible to avoid some minor, temporary problems. While practicing the path that leads to stable, unexcelled bliss, when we meet with problems, we are also meeting with the pure nature they embody: the possibility of liberation arises at the same time as the problem. We should also remember that we are practicing not just for our own benefit but for the benefit of the infinite living beings in all realms.

Negative spirits who create difficulties for Dharma practitioners will throw obstacles in the path of those who seek liberation. The harm they seek is to erase from the meditator's mind the desire to practice and attain liberation. Understanding this situation, practitioners should increase their diligence as much as possible and make as great an effort as they can to practice Dharma. This has two advantages. First, the obstacles can be stopped before they arise; and second, not losing all the work we put into practicing the path of liberation, we can continue along our journey.

Negative spirits who create difficulties for Dharma practitioners will throw obstacles in the path of those who seek liberation.

These days, some practitioners think that they must meditate intensely and attain all the qualities and special attributes of the Dharma, but they do not know well the nature of the view, meditation, or conduct taught in their own tradition. Even so, they insist that sometime very soon they will be enlightened and endowed with all the major and minor marks of the Buddha. When this does not happen, they say,

"The Dharma is useless. It doesn't work. I practiced hard, but it was all for nothing."

It is true that within the genuine Dharma, there is the path of the Secret Mantrayana, or the Vajrayana, which is very swift. There we find the oral instruction that states,

"If you meditate right now, you'll become awakened right now."

The Buddha and all his followers continuously taught this. However, if our minds lack the mental strength or capacity to accomplish such a swift path, there is little chance of swift liberation. The possibility of attaining liberation depends on whether the Buddha taught this path; however, achieving liberation depends on us. Therefore, if we do not put forth our full strength, the Dharma will enter inside but will not become manifest. If we do not have the capacity or the necessary attributes to attain the fruition of the practice in our tradition, we might then go to another tradition and, not attaining the result once again, disparage that tradition, saying that it Is not good. This pattern is the result of not being able to distinguish between a religious tradition and the individual, between the teachings and our limited self.

There are other benefits from receiving an empowerment, but the main point is for us to see the very nature of our mind.

In Buddhism, what we call "a religious tradition" means practicing a view or philosophy of the mind. All the paths found in these traditions are related to the mind. The Buddha and the incomparable masters who followed him taught that taming our minds is extremely important. Many of us have studied the major texts of Buddhism. (How much other types of study, like the sciences, benefit the mind ultimately is not clear.) If we receive a commentary on how to meditate on the preliminary practices or if we take an empowerment, these activities can benefit our minds. They are the heart of Dharma and have the purpose of establishing in our mind the habitual pattern for true happiness. If these do not help us, then receiving an empowerment does not impart its essential benefit: it is just placing a vase on our heads, and a great deal of work for the lamas.

There are other benefits from receiving an empowerment, but the main point is for us to see the very nature of our mind. It is beneficial if positive habitual patterns can be established within our mind, for example, an experience of the true nature that can blend with and benefit our mind. If this does not arise, then no matter how many texts we have studied or how many empowerments we have received, they will not be very useful. It is crucial to connect with the essential nature of our own mind.

For more information:

Related Books

An Ocean of the Ultimate Meaning

$24.95 - Paperback

The Third Karmapa's Mahamudra Prayer

$17.95 - Paperback

By: Rosemarie Fuchs & The Third Karmapa & XII Khentin Tai Situpa Rinpoche

$26.95 - Paperback

By: Jonathan C. Bell & Marie Aubele & Lama Kunsang & Maureen Lander & Lama Pemo

New and Recent Books on the Karmapas

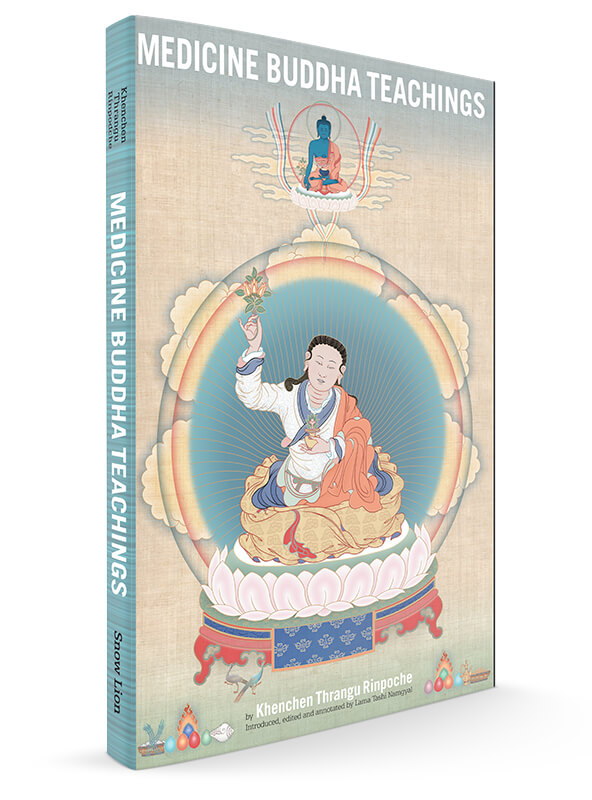

The second class of illness includes more serious, even dangerous, illnesses, but if one takes the appropriate medicines, one will recover from these as well. A modern update of this category would surely include many effective modern medical procedures, such as acupuncture, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, etc.

The third class of illness includes those for which medicines are of no use, illnesses from which one cannot recover simply through the use of medicines or other medical procedures. These illnesses, however, can be cured, and one can thereby recover one’s health, through the practice of appropriate spiritual techniques taught in the buddhadharma.

The fourth class of illness includes those which have a karmicly determined irreversibly terminal nature. When one’s body manifests such an illness, death is inevitable and no amount of medicine or medical procedure can prevent it. In fact, the use of medicines in such cases—with the exception of narcotics for pain—only serves to increase one’s suffering.

The teachings on the Medicine Buddha which follow in these pages, given by the extraordinary Tibetan meditation master and scholar Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche, are intended most particularly for those who are suffering from the third class of illness, illnesses for which no successful medical treatment has been found, but which are still curable through the practice of profound spiritual techniques. In the Buddhist tradition the most notable of these techniques are the spiritual practices associated with the Medicine Buddha. Through such practices, the innate healing powers inherent in the basic nature of all sentient beings can be uncovered and accessed. In this way sick persons can cure themselves of the illnesses that medicines and medical procedures are unable to cure.

As normal human beings we have a tendency to think that illnesses are physically based and require physical solutions. Therefore, it is reasonable to ask how it is possible that spiritual practice can help the body cure itself. This question becomes even more critical for those who have no faith in the miraculous powers of a creator god. But if one has confidence in or even an intimation of any kind of spiritual reality that transcends the limitations of a strictly material universe, then one will find oneself extremely interested in the answer to this question provided by the Buddhist tradition.

In the vajrayana tradition of Buddhism, we would answer this question—how one can cure oneself through spiritual practice—from two perspectives: from the perspective of the ultimate truth of the nature of reality, and from the perspective of relative truths, which discuss how things appear to us when we have not yet realized the ultimate truth of the nature of reality.

From the standpoint of ultimate truth, all phenomena, including all the phenomena that we misapprehend as physical matter, are empty of any inherent existence. Though they appear to be very solid and real to us, they are in truth mere illusory appearances lacking any substantial reality, like a light show in space, like the aurora borealis, a rainbow, an echo, a flash of lightning, a mirage, a magical display, a dream, an hallucination, like the images in movies and on television, or like the reflection of the moon in water. None of these illusory appearances, including what we take to be matter, have any true, separate, permanent, solid or substantial existence independent of ever-changing equally non-existent causes and conditions. When scientists today investigate and scrutinize the atoms which we for centuries have thought of as the building blocks of the material world, they find no indivisible and, therefore, permanent particles of matter. They find mostly space with variously described sorts of energies rushing around within it. These energies are also insubstantial, impermanent, and unpredictable. They cannot be said to have any kind of permanent existence. The more scientists investigate, the more illusory the nature of matter appears. The Buddha discovered this same truth in meditation 2,500 years ago, and the Buddhist tradition has been teaching it ever since.

All phenomena are ephemeral, constantly changing in the same way as the appearances within a kaleidoscope constantly change. None of these illusory appearances—including the appearances of sickness and disease, which are also mere empty appearances—have the power to cause us suffering unless we mistakenly apprehend them as real and substantial. When we misapprehend these appearances, when we take them to be real, we fixate on them and thereby cause them to solidify in our experience. This gives them the appearance of solid, substantial reality, and then in our lives these illnesses do, in fact, become for us very real and solid, and we suffer from them.

Still, though everything that we experience is empty of any kind of substantial existence, we still experience something. What is it that we experience? We experience mind.

In discussing the nature of things, or the nature of appearances, which in the ultimate analysis are merely empty, insubstantial radiations or light-manifestations of an equally empty and insubstantial, though luminous, mind, Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche expresses the teachings of the Buddha given 2,500 years ago in the third turning of the wheel of dharma, his third great cycle of teachings:

Before meditating, before recognizing things to be as they are, one will have seen the radiance of this mind as solid external things that are sources of pleasure and pain. But through practicing meditation, and through coming to recognize things as they are, you will come to see that all of these appearances are merely the display or radiance or light of the mind which experiences them.

When one is able truly to recognize sickness and disease as “merely the display or radiance or light of the mind which experiences them,” empty of any inherent substantial existence, then one’s suffering disappears.

Regardless of which of the first three categories of illness one is suffering from, if one is able to recognize its true nature—that it is merely the empty magical display or radiance or light of the mind which experiences it—one will experience no suffering, and depending on the level and completeness of this realization, one’s illness will dissolve in the empty pure primordial expanse, and one will be cured. Even if one is afflicted by the fourth category of illness and it is karmicly inevitable that one will die from that particular illness, one will die without suffering or fear, because all phenomena, including illness, are empty. They lack any kind of substantial, permanent reality independent of equally empty and interdependent causes and conditions. They are all merely insubstantial, ever-changing, kaleidoscopic light shows in the primordially pure open expanse of empty luminous awareness.

* * *

Most of the time, of course, we have no idea why we are ill. This comes about as a consequence of our present inability to recognize many of the various negative emotions that we suppress in our minds and to “see,” with the eye of wisdom, the karmic deeds, usually committed in previous lives, which are responsible for such emotions and for our illnesses. These recognitions are the prerequisite for “seeing” directly the relationship between negative mental/emotional states, evil deeds, and illnesses. The practice of the Medicine Buddha will also eventually remove the obscurations of mind that block such recognitions. In the meantime, if we understand the general principle of karmic cause and effect and have confidence in the possibility of spiritual purification, we can practice the Medicine Buddha and attain results long before the dawning of such spiritual insight.

All of these benefits come about because the basis of all illness is evil deeds and the emotional defilements that give rise to them. The practice of the Medicine Buddha is one of the most profound ways of purifying such deeds and defilements and the karmic imprints that they leave in the psychosomatic system in the form of illness and compulsive behavior. In this way, the Medicine Buddha removes the causes of our illnesses and the illnesses themselves.

* * *

From the teachings by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche