The following profile of is an excerpt from Meetings with Remarkable Buddhist Women by Lenore Friedman

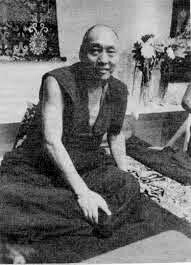

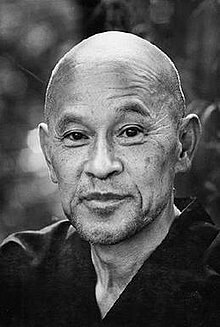

Yvonne Rand (image credit: Cuke.com)

For twenty years, ever since she met Shunryo Suzuki-roshi in 1966 and became Zen Center secretary four months later, Yvonne Rand has been intimately involved with the San Francisco Zen Center. She has held virtually every administrative office one can hold there, as well as working closely with Suzuki-roshi in a hundred ways for the rest of his life. Most recently she has lived and worked at Zen Center's facility in Marin County, Green Gulch Farm. Yvonne is an articulate, forthright, down-to-earth woman with whom it is invigorating to talk.

For her personally, two of the most important have been the practices of breath-walking and of the "half-smile," each of which she learned from the gentle Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh. "Learn to walk as a Buddha walks, to smile as a Buddha smiles," he says. "You can do it. Why wait until you become a Buddha? Be a Buddha right now, at this very moment!" Yvonne now practices the half-smile at stoplights and in grocery lines. Having breath-oriented practices that can be done for one to three breaths in the midst of activity has helped her experience a connectedness between the states of mind that arise in formal meditation and those arising in everyday life.

Other practices, especially with the precepts ( or rules for conduct), have been useful in examining deeper levels of herself, levels beyond action and language and thought. Layers of resistance and denial had to be plumbed, but now she experiences a much wider range of connection with other people. A vipassana forgiveness meditation, for example, has been useful in working with her "fierce, judging voice"-that voice so peculiar to American and Western minds, which Yvonne perceives as a wall or hindrance to being awake.

The precepts are "absolutely necessary ground" for her. "I can't be calm if my behavior is 'off.' " Sometimes she will use one precept as a mantra. Or she will hold, in the background of her mind, the image of a sieve, each of whose wires are the precept, through which she passes everything she does or thinks or says during the day. This ''creates a grid-large holes or smalldepending on the gross or subtle material which I intend to pass through it." This image came out of her working in her garden and noticing how different gradations of sieves determine the soil one can make. Images have more liveliness, she believes, if they come out of concrete experience.

Yvonne respects the way "practice grabs us. One of the precepts often jumps off the page at me, from an intuitive, barely conscious awareness of exactly where an 'edge' is at any moment." For instance, the precept about not stealing, or not taking what is not given (a translation Yvonne prefers), has expanded for her into an acceptance of things-as-they-are, which has been "very, very powerful." She says the precept acts like a rope along a pathway, and has allowed her to move through and be done with old patterns more effectively than any other single practice she has done up to now.

With its constant reminders of impermanence, she says, Buddhism helps us cultivate nonpossessiveness toward everything, including our personalities, or ''who it is we think we are."

Mindfulness practice, with its emphasis on being awake to whatever arises, teaches us to relate to our "stickiness and corruptibility" as grist for the mill. Aversion is an obstacle to seeing things as they are. Seeing leads to the possibility of transformation. "We're all corruptible," she says. But the degree to which we know our capacity for corruptibility ( that is, the roles and masks we wear that cause disharmony or harm to ourselves and others) is the degree to which we don't act on it.