Ruth Sonam

Ruth Sonam was born and grew up in Ireland and graduated from Oxford University with an MA in Modern Languages. She began studying with Geshe Sonam Rinchen in 1978 and started working as his interpreter in 1983. She was his interpreter at the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives from 1989 to 2012.

Ruth Sonam

-

The Three Principal Aspects of the Path$21.95- Paperback

The Three Principal Aspects of the Path$21.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

Eight Verses for Training the Mind$18.95- Paperback

Eight Verses for Training the Mind$18.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

How Karma Works$22.95- Paperback

How Karma Works$22.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

The Heart Sutra$22.95- Paperback

The Heart Sutra$22.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

The Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas$19.95- Paperback

The Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas$19.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

The Bodhisattva Vow$22.95- Paperback

The Bodhisattva Vow$22.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

The Six Perfections$21.95- Paperback

The Six Perfections$21.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment$19.95- Paperback

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment$19.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

By Atisha

Translated by Ruth Sonam

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

The Three Principal Aspects of the Path

| The following article is from the Summer, 1999 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

The Three Principle Aspects of the Path

By Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam

The wish for freedom, the altruistic intention to be of ultimate benefit to others, and the wisdom realizing emptiness constitute the three principal aspects of the path to enlightenment, three insights that form the indispensable support for all the practices of both sutra and tantra.

Having recognized that any state within cyclic existence involves suffering, the practitioner develops a strong wish for freedom. But to cut the root of cyclic existence it is necessary to know how things exist at the most fundamental level. Even if one has turned away from the causes of suffering and gained an undistorted understanding of reality, supreme enlightenment will remain out of reach without the altruistic intention to act selflessly for the good and happiness of all living beings.

In this teaching, Geshe Sonam Rinchen explains in clear and readily accessible terms Je Tsongkhapa's (1357-1419) short text on these three principal aspects of the path. This engaging exposition of the essential steps to enlightenment will be appreciated both by those with no previous exposure to Buddhism and by those who wish to undertake the practices of tantra, for which at least a sound understanding of these three is essential.

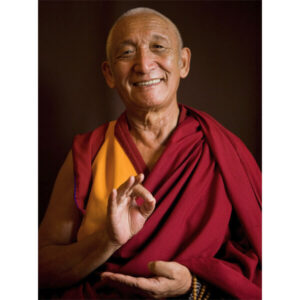

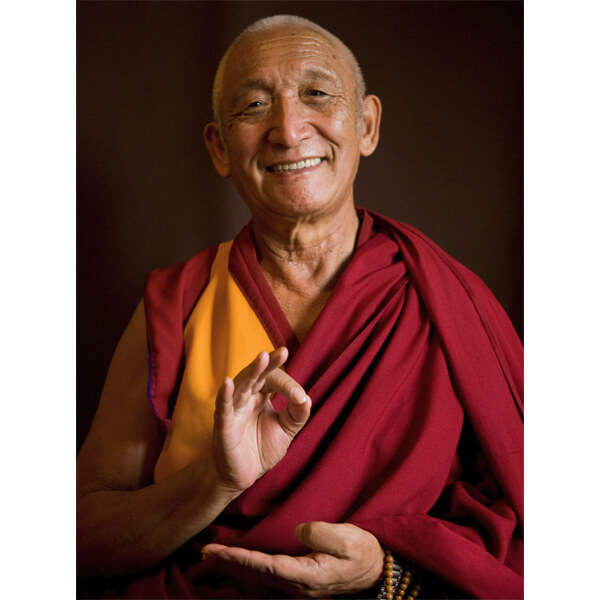

Geshe Sonam Rinchen was born in Tibet in 1933. He studied at Sera Je Monastery and in 1980 received the Lharampa Geshe degree. He is currently resident scholar at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala, India, where he teaches Buddhist philosophy and practice.

Ruth Sonam was born and grew up in Ireland and graduated from Oxford University with an M.A. in Modern Languages. She began studying with Geshe Sonam Rinchen in 1978 and has worked as his interpreter since 1983.

Following is a teaching from The Principal Aspects of the Path.

The Thought of Liberation

Wherever we are born in cyclic existence, whether in good or bad states, suffering is our faithful companion. There are six kinds of suffering which afflict us in all rebirths within cyclic existence. Uncertainty is the first. The very things which fascinate us, in which we place our hopes and to which we cling despite many disappointments, are utterly untrustworthy and unreliable. Our friends, from whom we expect so much, may well have been our bitter enemies in past lives and vice versa Those who are our friends now may become our foes later in life and our present foes may become our closest friends. A single word or look can change a relationship between morning and night. We join a friend for dinner, expecting to have a good time, and before the meal is over friendship has turned to enmity.

Just as drinking salt water cannot quench our thirst, no matter what we eat or drink or own, we never experience the expected satisfaction. The more we indulge, the more we crave. Our thirst for variety is never sated and as we pursue pleasure in the hope of fulfillment, we perform many negative actions which bring suffering. What we hope will still our hunger and bring gratification turns out to harm us. This lack of satisfaction is the second kind of suffering.

Through our ignorance we identify with a body formed from the sperm and ovum of others. Out of strong attachment to this body, which is quite unreliable and cannot last, we do much wrong. Despite our clinging and despite the time and energy we lavish on our troublesome body, we must relinquish it in the end and find a new one. This is the third form of suffering.

We cannot trust the glories of this world for there is constant flux between high and low, the fourth kind of suffering. The mighty fall from power and their subordinates take their places. The rich are reduced to penury overnight and the poor win the lottery. Everything changes.

The fifth form of suffering is that while we remain in cyclic existence we are alone and cannot depend on friendship. We spend some time with others, like guests in a hotel who stay for a while and then disperse in different directions, or like people who gather on market-day and then go their separate ways. Our friendships last just a short while. Shantideva says:

When you are born, you're born alone

And also when you die, you die alone.

If others cannot share your suffering,

What is the use of hindering friends?

We are born and die alone. In between we create much non-virtue for the sake of our friends and loved ones, yet they cannot share the suffering this will bring us. We alone must bear it. Understanding the transitory nature of friendship, we should love and help those we call our friends without being attached to them and without letting our feelings for them hamper our spiritual practice.

The sixth kind of suffering is that we are conceived and born again and again. Each time we have to give up our body and begin once more. Unless we intervene this process will continue endlessly. When we gain direct perception of reality, the end of this cycle of involuntary birth and death is finally in view.

If you contemplate this brief summary of the many drawbacks of cyclic existence, it will encourage you to recognize your unique good fortune in having a sound body and mind. Your future well-being or misfortune depends on how you use them, so take care to make the right choice. What could be better than to devote your energy to developing these three principal insights, beginning with the wish to leave cyclic existence? This is the best way to make your life meaningful.

Sometimes when we read or hear the teachings, we may feel that there is so much to remember eight of this, six of that and on and on. However, our memory has the capacity easily to store masses of facts. We absorb so much useless information from the media in the course of each day. If we see a practical application for what we learn from the teachings, all the better, since that will help us to retain and use it. But even if it does not seem immediately relevant, we can store what we learn for a time when it may come in useful. If we receive a precious gift, we feel happy and put it away carefully, even though we may not have any immediate use for it.

If, as it is said, just hearing the names of great masters like Asanga and Nagarjuna can protect us from bad rebirths, contemplating what they have written must surely provide greater protection. In his set of five treatises on the different levels Asanga defines the three kinds of suffering within which every kind of suffering can be included. He says the suffering of pain is that which is painful when it arises and while it lasts. That which is pleasurable when it arises and pleasurable while it lasts but is followed by pain when it stops, is the suffering of change. In fact everything impermanent that is produced through contaminated actions underlain by disturbing emotions is miserable and unsatisfactory.

Imagine you have a festering boil that has come to a head. When you pour cool water on it, you feel momentary pleasure. All contaminated pleasure and happiness is the suffering of change because the moment it stops, suffering of some kind starts. Asanga also views all mental activities and states of mind accompanying such contaminated pleasurable feelings as the suffering of change. The objects which induce these feelings are also included within this category of suffering because when they are removed, the pleasure ceases.

When disagreeable feelings arise and you experience pain, try hard not to allow this to make you angry, by remembering that your body and mind are a mass of causes which produce suffering at the slightest provocation.

Now imagine that salt is rubbed into your boil or that something sharp touches its head. This creates intense overt pain. Contaminated painful feelings constitute the suffering of pain. When nothing cooling nor anything irritating comes in contact with the boil, neither pleasure nor outright pain occur. Contaminated neutral feelings are said to be the pervasive suffering of conditioning because they contain the imprints, causes and seeds for suffering and for the disturbing emotions.

All pleasurable feelings are not the suffering of change, since there are feelings of pleasure which are uncontaminated, such as the pleasure accompanying direct perception of selflessness. All pain does not necessarily constitute true suffering, the first noble truth. For instance, someone who has perceived reality directly and attained an uncontaminated path of insight may experience mental pain on realizing how much they still don't know. This pain is part of a true path and not an example of true suffering, since it does not result from contaminated actions underlain by disturbing emotions.

All neutral feelings are not the pervasive suffering of conditioning, since there are three kinds of neutral feelings: virtuous, non-virtuous and unspecified. Virtuous neutral feelings may be contaminated and uncontaminated. The latter are not an instance of the pervasive suffering of conditioning.

The three kinds of contaminated feelings give rise to disturbing emotions. Pleasurable feelings arouse craving, while disagreeable feelings provoke anger. Neutral feelings lead to confusion which, for instance, wrongly takes what is impermanent to be permanent and what is unsatisfactory to be pleasurable. These disturbing emotions induce suffering. How obvious this is when craving makes us reach out for something whose attractiveness our incorrect mental approach has exaggerated! Unable to obtain what we have projected, which in reality does not exist, we suffer frustration and disappointment. This easily arouses anger, which is distressing now and creates future suffering. Confusion nourishes attachment and anger and makes us cling to suffering and its causes.

Practice focuses on interrupting the process by which feelings induce suffering. Instead of mistaking contaminated pleasurable feelings for real happiness, learn to recognize them as a form of suffering and stop attachment to them. When disagreeable feelings arise and you experience pain, try hard not to allow this to make you angry, by remembering that your body and mind are a mass of causes which produce suffering at the slightest provocation. To avoid the intense pain that comes when a head forms on the boil, you must deal with the boil itself. While you have a contaminated body and mind, pain cannot be avoided and will continue to occur.

From the Madhyamika viewpoint the three kinds of suffering are identified with painful, pleasurable and neutral feelings as described by Asanga. However, contaminated pleasurable feelings are not regarded as real pleasure but seen as a mere alleviation and diminution of suffering. They occur at the point when intense suffering of one kind has subsided and a new kind of suffering is beginning but has not yet become apparent. If this were real pleasure, it should increase as we continue to d# what induces it. But we know that as we go on eating or indulging in other sensual pleasures, the feelings and sensations eventually become disagreeable. Suffering on the other hand is real because the more contact we have with what induces it, the more intense the suffering becomes.

Wherever we are born in the six realms with a body and mind which have resulted from contaminated actions and disturbing emotions, suffering is present. If you are carrying a heavy load, you can find no relief until you put it down. The surest sign that your body and mind hold the seeds of disturbing emotions and suffering is the fact that even the most minor circumstance can precipitate both.

In The Three Principal Aspects of the Path Tsongkhapa explains the practices of the initial and intermediate levels in relation to developing the wish to leave cyclic existence. In the contemplation of suffering, emphasis on stopping your own suffering leads to a strong wish to be free from the cycle of involuntary birth and death, whereas concern to stop others' suffering gives rise to compassion. How can you develop the great compassion wishing to free others from their suffering, unless you recognize, are moved by and want to be rid of your own suffering?

When through such familiarity not even a moment's longing,

Arises for the marvels of cyclic existence,

And if day and night you constantly aspire to freedom,

You have developed the wish to leave cyclic existence.

As a result of repeatedly contemplating impermanence, the suffering of bad rebirths, the connection between actions and their effects and the suffering experienced in good rebirths, you come to see life in cyclic existence, even in the best celestial rebirth, as essenceless, and no worldly wealth, not even the fabulous riches of gods like Brahma and Indra, can tempt you.

A mother whose only child has gone missing can think of nothing else. Even her dreams are haunted by the longing to know what has happened and to hear some good news. This is her first thought on waking. When the thought of gaining liberation is, in the same way, foremost in your mind at all times, day and night, you have developed the wish to leave cyclic existence.

Related Books by Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Atisha's Lamp For the Path To Enlightenment

Atisha’s Lamp For the Path To Enlightenment

| The following article is from the Summer, 1997 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

By Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited and translated by Ruth Sonam

By Atisha

Photo by Peter Aronson

Atisha, the eleventh-century Indian Buddhist scholar and saint, came to Tibet at the invitation of the king of Western Tibet, Lha Lama Yeshe Wö, and his nephew Jangchub Wö. His coming initiated the period of the second transmission of Buddhism to Tibet, the revival which followed the persecution of Buddhism by the Tibetan king Langdarma in the ninth century, formative for the Sakya, Kagyu and Gelug traditions of Tibetan Buddhism.

Atisha's most celebrated text, entitled Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, was written for the Tibetan people at the request of Jangchub Wo. It sets forth the entire Buddhist path within the framework of three levels of motivation on the part of the practitioner, represented by the Hinayana, Mahayana and Vajrayana paths. Atisha's text thus became the source of the lamrim tradition, or graduated stages of the path to enlightenment, an approach to spiritual practice incorporated within all schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

Geshe Sonam Rinchen's lucid and engaging commentary draws out Atisha's meaning for today's practitioners with warmth and wit, bringing the light of this age-old wisdom into the modern world.

Here is an excerpt from Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

All Buddhas say the cause for the completion

Of the collections, whose nature is

Merit and exalted wisdom,

Is the development of higher perception. [34]

In the state of enlightenment our wisdom truth body is the fulfillment of our own highest aims, while our form bodies are for the well-being of others. In order to attain enlightenment we must complete the stores of merit and insight, and the best way to do this is by working for others. This is done most effectively with the help of extra-sensory perception, which depends upon the development of a calmly abiding mind. The text now explains the reasons for developing such higher perception and how to do so.

Just as a bird with undeveloped

Wings cannot fly in the sky,

Those without the power of higher perception

Cannot work for the good of living beings. [35]

Just as hens can't fly because their wings are not sufficiently developed for flight, our work for others is hampered without the different forms of higher perception.

The merit gained in a single day

By one who possess higher perception

Cannot be gained even in a hundred lifetimes

By one without such higher perception. [36]

Enormous merit can be created in . even a single day if we have these forms of super-knowledge, merit that would otherwise take aeons to develop.

Those who want swiftly to complete

The collections for full enlightenment

Will accomplish higher perception

Through effort, not through laziness. [37]

If we are sincere in our wish to gain enlightenment swiftly for the sake of all beings, which is what we promise to do when we take the Bodhisattva vow, we must develop these different types of higher perception as the surest way of completing the great stores of merit and insight. We will only gain them if we know how and set about creating the necessary causes and conditions. If we are lazy about doing this our wish to develop them is futile.

Without the attainment of calm abiding,

Higher perception will not occur.

Therefore make repeated effort

To accomplish calm abiding. [38]

How is it done? By practicing placement meditation and developing meditative stabilization in which bliss, the outcome of total mental and physical pliancy, is experienced. This is calm abiding. Maitreya's Ornament for the Mahayana Sutras describes the nine stages of increasing mental stability and clarity which lead to this state. His Differentiation of the Middle Way and the Extremes describes the five faults and how to overcome them through the application of eight counteractions.

When trying to develop a calmly abiding mind, continuous practice with the same focal object is essential. If we are trying to make fire by rubbing two sticks together, we can't break off and begin again after some time. Success depends on continuity.

In our efforts to help others we are severely limited by lack of knowledge. There is so much we don't know about ourselves and the working of our own mind, let alone about others, their needs and their capacities. Usually when we try to help we are guessing, but sometimes our guess is right, sometimes wrong. With the different forms of higher perception or superknowledge our help will always be appropriate.

The first form of higher perception is knowledge of miraculous feats. With this we can travel to Buddha lands and make offerings to the enlightened ones. We can effortlessly find and gather together students with whom we have a strong karmic connection. Having done this, we will be able to give them good help through our knowledge of others' minds, the second kind of knowledge, which lets us discern their disposition, interests, abilities and inclinations. We can then teach them in a way which is entirely suited to their needs. The third of the higher perceptions is clairaudience, which allows us to hear what is going on in Buddha lands. This is considerably cheaper than the telephone! It enables us easily to learn the languages of our students in order to communicate with them directly.

The fourth kind of higher perception is knowledge of past places. This refers to memory of past rebirths and enables us to recall the spiritual teachers, people and practices with which we have had a previous close association. We can then seek out those teachers again and continue the practices with which we have already gained familiarity, thereby making faster progress. The fifth is clairvoyance regarding others' feelings of happiness and unhappiness. When we understand what they are experiencing our help will address their needs. The sixth is knowledge of the end of contamination. This is a personal understanding gained through meditation and higher perception of the paths which lead to liberation and of how to communicate them to others.

Since Bodhisattvas are entirely concerned with others' well-being, they only use these powers for beneficent purposes. Celestial beings, beings in the intermediate state and hungry spirits are bom with limited and partial forms of higher perception. If we happen to have a dream or intuition that comes true, we immediately suspect that we may possess clairvoyant powers. Bodhisattvas make a conscious and concerted effort to develop reliable forms of extra-sensory perception for the sake of helping others. The heightened state of concentration which forms the basis for this is the same whether attained by Buddhists or non-Buddhists. When accompanied by sincere refuge in the Three Jewels it is a Buddhist practice. When accompanied by a strong wish to gain freedom from cyclic existence it acts as a cause for liberation, while the intention to attain enlightenment for the sake of all living beings makes it a Mahayana practice.

A calmly abiding mind is necessary for attaining special insight according to the sutra tradition and for attaining the stages of generation and completion in the practice of tantra. While Atisha stresses its importance as the foundation for higher perception, Shantideva and other great masters point out that only through special insight into reality can we eliminate the ignorance which lies at the root of cyclic existence, and that such special insight cannot be developed without a calmly abiding mind.

Even if we do not succeed in developing this heightened state of meditative stabilization, we can enhance our mental stability and concentration. This will make our meditation, our daily prayers and practice of virtue much more effective. If we wish to achieve anytliing powerful we must learn to concentrate. In the chapter on maintaining mental alertness in Engaging in the Bodhisattva Deeds Shantideva reminds us that distraction weakens everything we do:

The one who knows reality has said

That even if recitation and austerities

Are practiced for a long period, their practice

With a distracted mind is meaningless.

The explanation of how to gain higher perception through developing a calmly abiding mind has three parts. First the prerequisites are discussed, then the method of cultivating calm abiding is described and finally the great benefits of developing it are mentioned.

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

$19.95 - Paperback

By: Atisha & Geshe Sonam Rinchen & Ruth Sonam

Books Related to Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

The Six Perfections

| The following article is from the Winter, 1998 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

The Six Perfections

An Oral Teaching

By Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited and translated by Ruth Sonam

The Six Perfections of generosity, ethical discipline, patience, enthusiastic effort, concentration, and wisdom are practiced by Bodhisattvas who have the supreme intention of attaining enlightenment for the sake of all living beings. These six are called perfections because they give rise to complete enlightenment the liberation from disturbing attitudes and emotions and the removal of the obstructions to complete knowledge of all phenomena.

Practicing the six perfections insures that we will have an excellent body and mind in the future and leads to even more favorable conditions for development than we experience at present. Generosity results in the enjoyment of ample material resources, ethical discipline gives a good rebirth, and patience leads to an attractive appearance and supportive company, enthusiastic effort endows us with the ability to complete what we undertake, concentration makes the mind invulnerable to distraction, and through the growth of wisdom we will be capable of discriminating between what should be cultivated and discarded. These six incorporate all of the advice that the Buddha gave on the Bodhisattva way of life, i.e., every practice needed to fully develop and enlighten oneself and others.

Geshe Sonam Rinchen was born in Tibet in 1933. He studied at Sera Je Monastery and in 1980 received the Lharampa Geshe degree. He is currently resident scholar at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala, India, where he teaches Buddhist philosophy and practice.

Ruth Sonam was raised in Ireland and graduated from Oxford University with an M.A. in Modern Languages. She began studying with Geshe Sonam Rinchen in 1978 and has worked as his interpreter since 1983. They have published Yogic Deeds of Bodhisattvas, a translation of Gyel-tsap's commentary on Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas, Alisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment and The Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas, a commentary on mind-training.

Here is an excerpt from The Six Perfections

To dream of reaching a destination is not enough you must pack your bags and set out on the journey. Bodhisattvas who are intent on enlightenment for the sake of all living beings make this a reality by adopting a certain way of life. All the advice the Buddha gave on this way of life and on the multifarious activities in which Bodhisattvas engage can be subsumed in the six perfections of giving, ethical discipline, patience, enthusiastic effort, concentration and wisdom. They comprise every practice needed to fully ripen oneself and others.

There are four principal ways of ripening others, or helping them to spiritually mature. This is done through generosity in order to establish a positive relationship with them, through interesting discussion regarding what is of true benefit, through encouraging them to implement what they have understood and by acting accordingly oneself. Since these activities are included within the practices of the six perfections, they do not need to be explained separately.

In his Ornament, for the Mahayarm Sutras Maitreya explains why there are specifically six perfections and shows how they comprise all the Buddha's teaching on the conduct of Bodhisattvas. The great Tibetan master Tsongkhapa cites this work by Maitreya in his Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path which will serve as the basis for the following explanation of the six perfections.

Maitreya points out that to accomplish the extensive practices in which Bodhisattvas engage for the attainment of ultimate well-being, namely an enlightened being's body, possessions, environment and companions, they need temporary well-being. This depends on an uninterrupted series of good rebirths in which they enjoy excellent conditions for continued spiritual practice, such as plentiful resources, a strong body and mind and supportive fellow practitioners. Nagarjuna's Precious Garland defines temporary well-being or high status as the body and mind of celestial and human beings and the happiness they enjoy. To gain this we need faith and ethical discipline.

According to the sutras it takes many such rebirths to create the two great stores of merit and insight necessary for attaining enlightenment. If sutra and t.antra are practiced together, enlightenment can be attained in a single lifetime by developing the kind of exalted wisdom which simultaneously and swiftly creates insight and merit. The ability to do this depends entirely on the high calibre of the practitioner and is firmly based on the three principal paths of insight the wish to be free from cyclic existence, the altruistic intention and a correct understanding of reality.

Practice of the six perfections insures that we will gain an excellent body and mind and even more favorable conditions for effective practice than those we enjoy at present. The Buddha taught that generosity leads to the enjoyment of ample resources. Since human happiness is intimately connected with material well-being, the practice of generosity is explained first in the context of the six perfections, the four ways of maturing others and the three major ways of creating positive energy.

However, generosity cannot protect us from a bad rebirth in which it is impossible to make good use of these resources. Ethical discipline, another way of creating positive energy, insures a good rebirth, while the practice of patience leads to an attractive appearance and supportive friends and companions. Cultivating enthusiastic effort endows us with the ability to complete what we undertake. However, even if we enjoy these conducive circumstances, our actions will not be effective as long as our mind is scattered and distracted by disturbing emotions. Fostering concentration, the third way of creating positive energy, makes our mind invulnerable to distraction. Unless we also possess the wisdom to discriminate between what needs to be cultivated and what must be discarded, we will consume the stock of positive energy created by previous wholesome actions without creating new positive energy for good future rebirths. By cultivating wisdom now we also insure that we will never lack wisdom in the future.

As practitioners of the Great Vehicle our wish to possess such an excellent body and mind is first and foremost for the benefit of others, and the six perfections play an essential part in accomplishing their well-being. Through material generosity we alleviate their poverty and build up a constructive relationship with them, but if at the same time we harm them physically or verbally, our generosity will be of very limited value. Restraint from such actions is ethical discipline, which cannot be maintained if we respond to harm with the wish to retaliate. Patience thus acts as a vital support for the practice of ethical discipline. By not retaliating we prevent conflict from escalating and help our opponents not to create further negative actions. Our lack of vindictiveness may even win them over and present an opportunity to help them.

Enthusiastic effort is needed to complete what we undertake for others, while a stable concentrated mind and clear understanding of what is and is not constructive are also essential. The attainment of heightened concentration enables one to please and assist others through miraculous feats. Having made them receptive in these ways, wisdom is used in providing them with excellent advice, dispelling their doubts and showing them clearly how they can free themselves from cyclic existence. By fulfilling the needs of others through practicing the six perfections everything we wish for ourselves will be accomplished.

Each perfection is more difficult to practice and more subtle than the preceding perfection from which it develops. If we are not attached to what we own and do not seek to acquire further possessions, we are in a good position to maintain ethical discipline. While practicing non-violence, if we can tolerate suffering and bear harm both from the animate and inanimate, we can undertake any task without feeling discouraged. The resultant energy enables us to make joyous effort in positive actions of all kinds. These causes give rise to the single-pointedness of a calmly abiding mind which can be used for gaining special insight into reality.

Accustoming ourselves to giving will make us less attached to things. Guarding against carelessness through ethical discipline stops coarser forms of waywardness. The ability to accept and bear suffering prevents us from abandoning living beings. Unflagging enthusiasm is the way to increase virtue. Mental and physical pliancy attained through concentration stop disturbing emotions from manifesting, while close analysis increases wisdom and ultimately eliminates disturbing emotions and their imprints completely.

In general, practice of the first three perfections is particularly directed towards others' benefit, while practice of the last two is important for personal development. In both cases enthusiastic effort is vital, for freedom from both worldly existence and from a state of solitary peace is gained through wisdom, which requires the development of heightened concentration. This is impossible without enthusiastic perseverance.

The Tibetan words which are translated as perfection means gone beyond. These practices are called perfections because they are practiced by Bodhisattvas with the supreme intention of attaining enlightenment for the sake of all living beings. A perfection surpasses other practices in the way that exalted beings surpass ordinary beings, the ultimate surpasses the conventional, nirvana surpasses cyclic existence, and understanding surpasses nescience.

A Bodhisattva's practice of the perfections gives rise to complete enlightenment, a state beyond both worldly existence and personal peace in which generosity, ethical discipline, patience, enthusiastic effort, concentration and wisdom have been perfected. Thus the cause is called by the name of the result. Practice of the perfections takes one to the other shore beyond the ocean of cyclic existence to a state in which the two kinds of obstructions those to liberation, formed by the disturbing attitudes and emotions, and those which prevent complete knowledge of all phenomena have been completely eliminated.