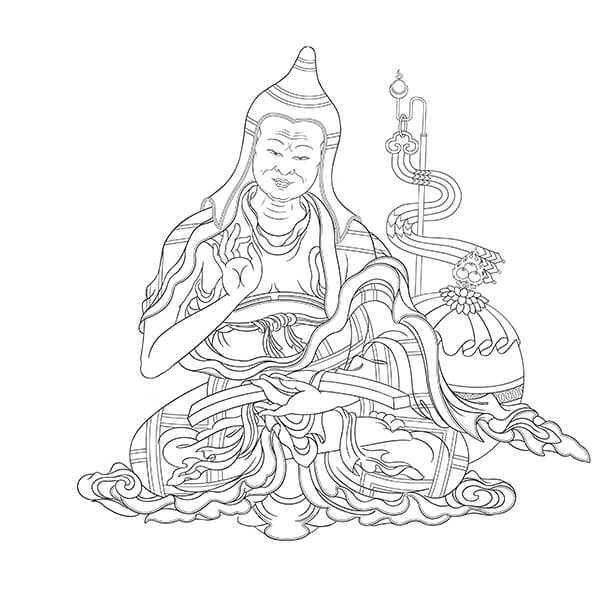

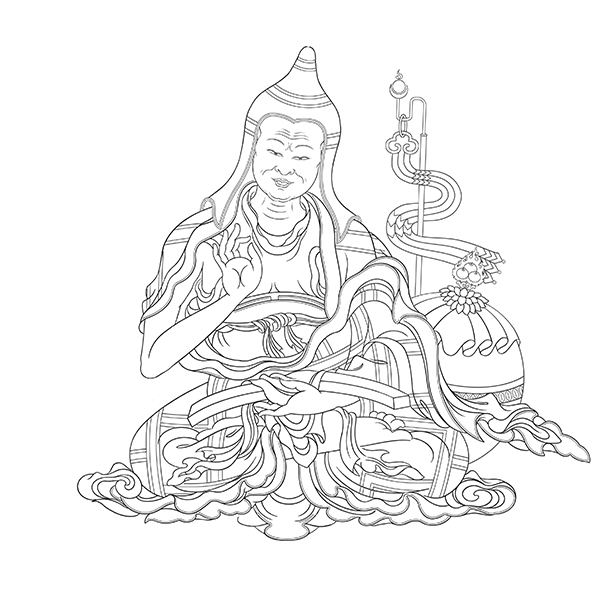

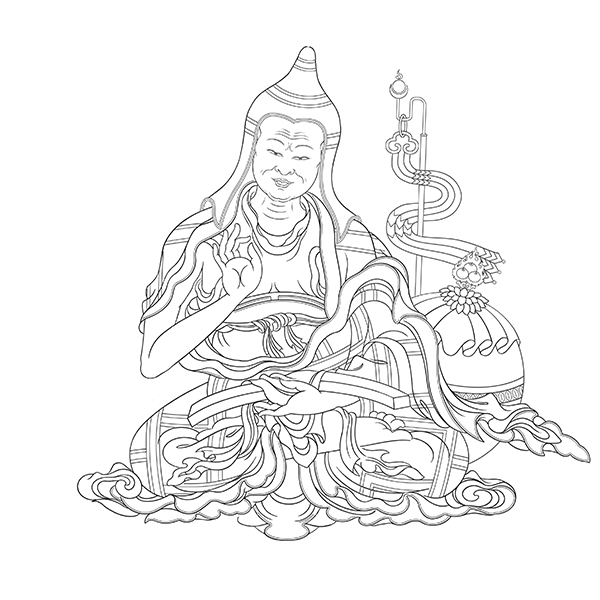

Shantideva

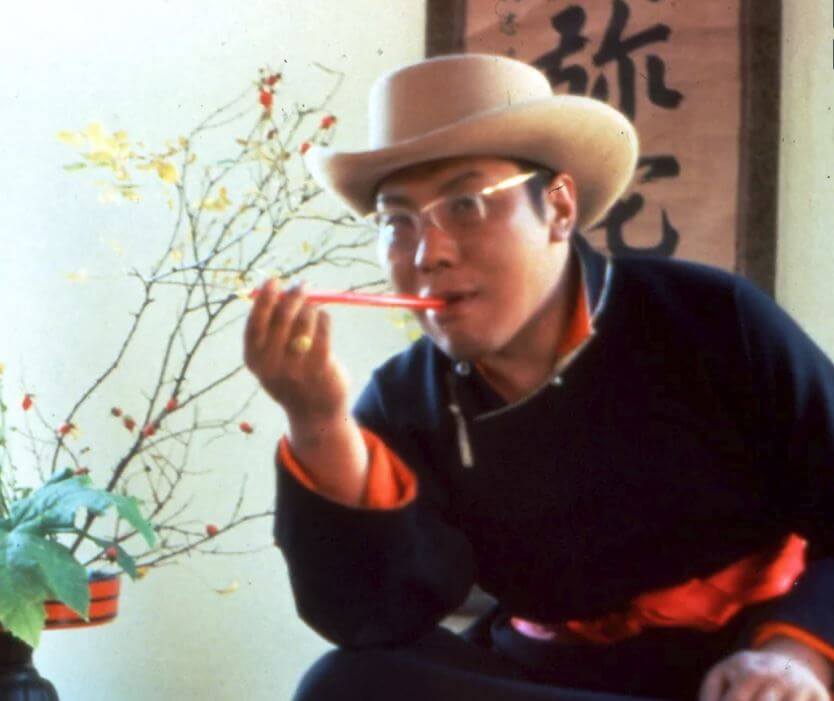

Shantideva was a scholar in the eighth century from the monastic university Nalanda, one of the most celebrated centers of learning in ancient India. According to legend, Shantideva was greatly inspired by the celestial bodhisattva Manjushri, from whom he secretly received teachings and great insights. Yet as far as the other monks could tell, there was nothing special about Shantideva. In fact, he seemed to do nothing but eat and sleep. In an attempt to embarrass him, the monks forced Shantideva's hand by convincing him to publicly expound on the scriptures. To the amazement of all in attendance that day, Shantideva delivered the original and moving verses of the Bodhicharyavatara. When he reached verse thirty-four of the ninth chapter, he began to rise into the sky, until he at last disappeared. Following this, Shantideva became a great teacher.

Shantideva

-

Entering the Way of the Bodhisattva$21.95- Paperback

Entering the Way of the Bodhisattva$21.95- PaperbackTranslated by Khenpo David Karma Choephel

By Shantideva -

The Way of the Bodhisattva$24.95- Hardcover

The Way of the Bodhisattva$24.95- HardcoverBy Shantideva

Translated by Padmakara Translation Group

Read by Wulstan Fletcher -

The Way of the BodhisattvaDigital Audio

The Way of the BodhisattvaDigital AudioBy Shantideva

Translated by Padmakara Translation Group

Read by Wulstan Fletcher The Way of the Bodhisattva$16.95- Paperback

The Way of the Bodhisattva$16.95- PaperbackBy Shantideva

Translated by Padmakara Translation Group

Foreword by H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Read by Wulstan Fletcher A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life$16.95- Paperback

A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life$16.95- PaperbackBy Shantideva

Translated by Vesna A. Wallace

Translated by B. Alan Wallaceper page

GUIDES

Indian Mahayana Masters of the 2nd-8th Centuries

The Indian Masters

Indian Mahayana Masters from the 2nd-8th Centuries

The Tibetan traditions all look back to India as the source of wisdom. There were countless masters all over India, north and south, east (including present-day Bangladesh) and west (including present-day Pakistan). The Mahayana reached its full expression during this period, and what follows is a partial but growing list of Reader Guides to these masters.

The Seventeen Pandits of Nalanda

2nd through 11th centuries

Tibetan Buddhism is none other than the Buddhism of India in the tradition of Nalanda, the great center of Buddhist learning that was located in present-day Bihar, India. There are seventeen great scholars profiled here, including Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Asanga, Vasabandhu, Buddhapalita, Dignaga, Bhavaviveka, Vimuktisena, Chandrakirti, Dharmakirti, Shantideva, Shantarakshita, Kamalashila, Haribhadra, Gunaprabha, Shakyaprabha. and Atisha.

Nagarjuna

(2nd century....and beyond)

The great master closely associated with the Perfection of Wisdom

Shantideva and the Way of the Bodhisattva

8th century

The great master Shantideva is the author of two very important texts. The first is the Śikṣāsamuccaya, or Training Anthology which is a compilation of many works. The second is the Bodhicharyavatara, or Way of the Bodhisattva. This Reader Guide focuses on the latter work.

Asanga

4th century

The great Mahayana figure who is a key explicator of Yogacara, and also received the Five Maitreya texts from Maitreya.

Xuanzang (602-664 CE)

7th century

While not an Indian master, we wanted to include Xuanzang, certainly one of the most important figures in Buddhist history. His 16 year pilgrimage from his home in China throughout the Buddhist world is almost The Odyssey of the Buddhist literature. His translation and preservation of texts, as well as the account of his journey, had come down to us through the ages and is well worth a deep exploration.

A Reader's Guide to Shantideva and the Way of the Bodhisattva

and The Way of the Bodhisattva

A Reader's Guide to the Way of the Bodhisattva

The great nineteenth-century master Patrul Rinpoche, author of The Words of My Perfect Teacher and revered by all Tibetan Buddhists, was known for his wandering ascetic lifestyle, eschewing fame, generous offerings, and all but the most meager possessions. However, wherever he went throughout his peripatetic life, he carried with him a copy of Shantideva's Bodhicharyavatara, which we know now as The Way of the Bodhisattva or A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life. Renowned for his encyclopedic knowledge and ability to transmit the wisdom of Prajnaparamita and Dzogchen, Patrul Rinpoche spent his life constantly teaching this text, encouraging students to read it and study it over and over again-hundreds of times. Why this focus from him and millions of masters and practitioners before and after?

Below is a guide to help practitioners answer this question for themselves and go deeper and deeper into this essential work. For a bit of history, you can also see our post on its story.

Jump To: Translations | Commentaries | Chapter-Specific Works | Additional Works | Resources

Translations of the Bodhicharyavatara

Entering the Way of the Bodhisattva: A New Translation and Contemporary Guide

This modern translation of an essential Mahayana Buddhist text captures the meaning and musicality of Shantideva's original verse and a commentary to its profound depths by the translator David Karma Choephel , one of the very few western Khenpos.

This is a fresh translation to, and commentary on the Bodhicaryavatara or Entering the Way of the Bodhisattva, perhaps the most renowned and thorough articulation of the bodhisattva path. Written by the eighth-century Indian monk Shantideva, Entering the Way of the Bodhisattva is a guide to becoming a bodhisattva, someone who is dedicated to achieving enlightenment in order to benefit all beings.

After the full translation, Khenpo David Karma Choephel gives his own commentary, explaining the key points of each chapter with clarity and wisdom. Combining a uniquely poetic translation with detailed analysis, this book is a comprehensive guide to developing oneself in service of others. Teachings that have been at the heart of Mahayana practice for centuries are given new life, and the supporting commentary makes the text accessible and applicable to practitioners. Readers interested in the bodhisattva path will find this a comprehensive resource filled with captivating verse and incisive interpretations.

Paperback | eBook

$21.95 - Paperback

Shambhala Library Hardcover | Paperback | eBook | MP3 audio download.

$24.95 - Hardcover

The Way of the Bodhisattva

By far the best-selling translation is from the Padmakara Translation Group entitled The Way of the Bodhisattva. This was translated with reference primarily to the Tibetan and following the commentary of Khenpo Kunpel, the nineteenth-century Nyingma master renowned for his spiritual realization and instrumental in the preservation of the oral traditions and teachings of his tradition.

This edition also includes a ten-page biography of Shantideva as well as selections on tonglen, or exchanging oneself with others, from Khenpo Kunpel's commentary.

A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life:

Another excellent translation is from Alan and Vesna Wallace, translated as A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life. The Wallace's translation is based both on Sanskrit and Tibetan sources and was guided by Tibetan commentaries, notably of Gyaltsap-Je.

Another version to note is Kate Crosby and Andrew Skilton's translation from Oxford University Press. All these translations expose different facets of the text, while the translators' introductions each illuminate it in different ways and are well-worth seeking out.

Paperback | eBook

$16.95 - Paperback

Commentaries

Paperback | eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Nectar of Manjusri's Speech: A Detailed Commentary on Shantideva's Way of the Bodhisattva

by Khenpo Kunzang Pelden, based on Patrul Rinpoche's teachings

While Patrul Rinpoche did not compose a work on the Way of the Bodhisattva, he taught it constantly, over one hundred times from beginning to end. It had fallen into disuse outside a few monastic centers, and it is thanks to Patrul Rinpoche this text became integral to all the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Luckily for us, one of his most dedicated students, Khenpo Kunzang Pelden or Khenpo Kunpel, compiled these teachings he received from Patrul Rinpoche and composed The Nectar of Manjusri's Speech: A Detailed Commentary on Shantideva's Way of the Bodhisattva.

Paperback | eBook | Pocket Edition | mp3 Audio

$21.95 - Paperback

For the Benefit of All Beings: A Commentary on The Way of the Bodhisattva

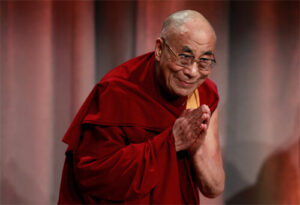

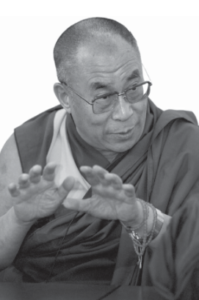

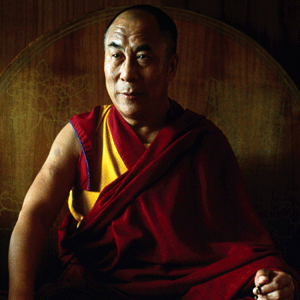

by the Dalai Lama and the Padmakara Translation Group

Based on teachings His Holiness gave in Dordogne, France in 1991, For the Benefit of All Beings, translated by the Padmakara Translation Group, gives an overview and commentary on each chapter of the text, distilling the key messages on the benefits of bodhichitta, offering and purification, carefulness, attentiveness, patience, endeavor, concentration, wisdom, and dedication. His Holiness said,

"I received the transmission of the Bodhicharyavatara from Tenzin Gyaltsen, the Kunu Rinpoche, who received it himself from a disciple of Dza Patrul Rinpoche, now regarded as one of the principal spiritual heirs of this teaching. It is said that when Patrul Rinpoche explained this text, auspicious signs would occur, such as the blossoming of yellow flowers, remarkable for the great number of their petals. I feel very fortunate that I am in turn able to give a commentary on this great classic of Buddhist literature."

Paperback | eBook | CD | Digital Download

$29.95 - Paperback

Becoming Bodhisattvas: A Guidebook for Compassionate Action

by Pema Chōdrōn

In Becoming Bodhisattvas: A Guide to Compassionate Action (previously published as No Time to Lose: A Timely Guide to the Way of the Bodhisattva), Ani Pema Chödrön talks about her relationship with the text and said it was not always easy:

"Some people fall in love with The Way of the Bodhisattva the first time they read it, but I wasn't one of them. Truthfully, without my admiration for Patrul Rinpoche, I wouldn't have pursued it. Yet once I actually started grappling with its content, the text shook me out of a deep-seated complacency, and I came to appreciate the urgency and relevance of these teachings. With Shantideva's guidance, I realized that ordinary people like us can make a difference in a world desperately in need of help."

Giving Our Best: A Retreat with Pema Chodron on Practicing the Way of the Bodhisattva

by Pema Chödrön

Pema Chödrön's teachings on this text are also available in the form of Giving Our Best: A Retreat with Pema Chödrön on Practicing the Way of the Bodhisattva. This is a rare and wonderful presentation from a live teaching that brings the teachings into real life, present-day situations.

Chapter-Specific Commentaries

We have two books on the Patience or fourth chapter and three on the Wisdom, or ninth chapter.

Paperback | eBook | Audiobook

$16.95 - Paperback

Peaceful Heart: The Buddhist Practice of Patience

An introductory guide to cultivating patience based on The Way of the Bodhisattva's Fourth Chapter on patience, and opening your heart to difficult circumstances from leading Buddhist teacher, Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche.

Also available as an audiobook

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche talks about his book at the Jaipur Literature Festival

Paperback | eBook

$18.95 - Paperback

Perfecting Patience: Buddhist Techniques to Overcome Anger

His Holiness the Dalai Lama also has a book devoted to Shantideva's chapter on patience. Here His Holiness relates that:

"Shantideva observes that from one point of view, as pointed out earlier, when the other person inflicts harm or injury upon one, that person is accumulating negative karma. However, if one examines this carefully, one will see that because of that very act, one is given the opportunity to practice patience and tolerance. So from our point of view it is an opportune moment, and we should therefore feel grateful toward the person who is giving us this opportunity. Seen in this way, what has happened is that this event has given another an opportunity to accumulate negative karma, but has also given us an opportunity to create positive karma by practicing patience. So why should we respond to this in a totally perverted way, by being angry when someone inflicts harm on us, instead of feeling grateful for the opportunity?"

Paperback | eBook

$16.95 - Paperback

Perfecting Wisdom: How Things Appear and How They Truly Are

by The Dalai Lama

The ninth chapter of the Bodhicaryavatara, on wisdom, is considered one of the most profound and requires deep study and practice to truly understand. In this work, His Holiness the Dalai Lama focuses on this chapter and its application. Here, His Holiness goes deep into the subjects of the methods needed to cultivate wisdom, what identitylessness means, and how the notion of true existence is refuted.

The Wisdom Chapter

by Mipham Rinpoche, based on teachings he received from Patrul Rinpoche

Patrul Rinpoche, also imparted teachings to Mipham Rinpoche, who based his understanding on these when he wrote his commentary on the famous (and famously challenging) ninth chapter of The Way of the Bodhisattva, now translated as The Wisdom Chapter.

Hardcover | eBook

$78.00 - Hardcover

The Center of the Sunlit Sky: Madhyamaka in the Kagyu Tradition

by Karl Brunnholzl

Another in-depth look at this text - in particular the ninth chapter - is Pawo Rinpoche's explanation included in The Center of the Sunlit Sky. In just under 200 pages of this work, in addition to being a commentary on Shantideva's work generally, Pawo Rinpoche provides several long accounts on such topics as Madhyamaka in general, the distinction between different branches of Madhyamaka philosophy, prajña, emptiness, conventional and ultimate reality, and the nature and qualities of Buddhahood. It describes the four major Buddhist philosophical systems and how the Mahayana represents the words of the Buddha. In addressing the issue of so-called Shentong-Madhyamaka, he also elaborates on the lineage of vast activity and shows that it is not the same as mind only.

This is available in both hardcover and eBook (see Additional Formats).

Additional Works on The Way of the Bodhisattva

Paperback | eBook

$27.95 - Paperback

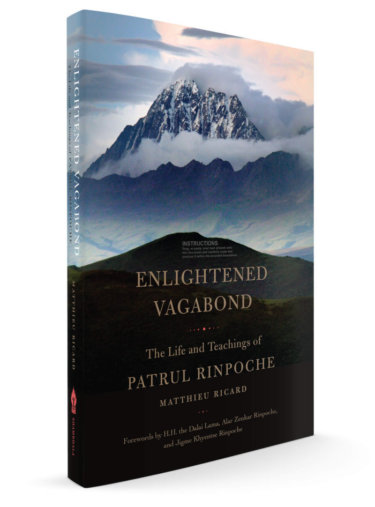

Enlightened Vagabond: The Life and Teachings of Patrul Rinpoche

by Matthieu Ricard

2017 also saw the release of Enlightened Vagabond, the collected stories about Patrul Rinpoche who led a revival of the focus and immersion of students on this text. The stories often revolve around him teaching on this text which he did countless times. Here is an example:

Patrul and the Prescient Monk

—from Enlightened Vagabond

Patrul was famous for his teachings on The Way of the Bodhisattva. He might take days, weeks, or months to comment on the entire text, teaching at whichever level of complexity was most suitable to the occasion, from brief and quintessential to extensive and complex. Often, he’d advise students to read the text before he gave his commentary. After he was done, he’d tell students to read it another hundred times.

"Patrul himself had received teachings on The Way of the Bodhisattva more than a hundred times. He taught the text more than a hundred times, yet even so, he used to say that he had not grasped its full meaning. One night, a monk at Trago Monastery dreamed that he saw a lama who he felt was Shantideva in person, the author of The Way of the Bodhisattva. The next morning, when a wandering lama arrived at Trago Monastery, the monk recognized him: He looked just like the figure who had appeared in his dream the night before! The monk approached the lama—who in fact was Patrul Rinpoche. Bowing respectfully, he requested that he teach The Way of the Bodhisattva. Bowing back, the lama agreed. Patrul gave the teachings. When he left, the monk who had seen him in his dream went with him, accompanying him along the way for several days’ walk."

Paperback | eBook

$22.95 - Paperback

Destroying Mara Forever: Buddhist Ethics Essays in Honor of Damien Keown

Another work that should be mentioned is Destroying Mara Forever, a collection of essays on Buddhist ethics including three pieces focused on this text.

The first is by Barbara Clayton entitled Santideva, Virtue, and Consequentialism.

The second, by Paul Williams, is entitled Is Buddhist Ethics Virtue Ethics? The final piece that is Shantideva-specific is Daniel Cozort's Suffering Made Sufferable: Santideva, Dzongkaba, and Modern Therapeutic Approaches to Suffering's Silver Lining. These three pieces explore different ethical implications and significance of Shantideva's work

Additional Resources

Please visit The Way of the Bodhisattva: An Immersive Workshop for more on Shantideva's work, or sign up for our Tibetan Buddhist email list for more information.

The Way of the Bodhisattva Resources

Patrul Rinpoche: A Reader's Guide

Praise to Patrul Rinpoche

Outwardly, you are the Son of the Victorious Ones, Shantideva.

Inwardly, you are the saint, the conqueror Shavaripa.

Secretly, you are the supreme sublime being Dug-ngal Rangdröl, actual self-liberator of the suffering of beings.

Jigme Chökyi Wangpo, I pray to you.

— by Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, from Thinley Norbu Rinpoche's Sunlight Speech That Dispels the Darkness of Doubt

Jump To: His Life | Foundations | Propitious Speech | Mahayana | Tantra | Dzogchen | More

The Life of Patrul Rinpoche

Eastern Tibet in the nineteenth century was teeming with some of the most remarkable teachers to have walked on this earth.

Standing vividly out among them was Dza Patrul Orgyen Jigme Chökyi Wangpo, commonly known to us as Patrul Rinpoche. Considered one of the three main incarnations of Jigme Lingpa, the impact that this wandering yogi made on Buddhist practice cannot be overstated.

Biographical sketches of him can be found in Tulku Thondup's Masters of Meditation and Miracles, Khenpo Kunpel's A Vase of Nectar to Inspire the Faithful: A Biography of Patrul Rinpoche, Nyoshul Khen Rinpoche's A Marvelous Garland of Gems, Alak Zenkar Rinpoche's brief biography on Lotsawa House, and as several of the works listed below.

But perhaps the best place to start is in Matthieu Ricard's Enlightened Vagabond: The Life and Teachings of Patrul Rinpoche. Ricard has spent his life with some of the most amazing teachers of the 20th century, many of them heirs to the practice tradition of Patrul Rinpoche and the oral tradition preserving the stories of Patrul Rinpoche, which have been told since his days as a peripatetic wandering in the hills and mountains of eastern Tibet. This book is filled with stories and teachings that will make you laugh and cry and leave you in awe. It is an essential book for those inspired by Patrul Rinpoche's life, works, and wisdom.

What follows is a guide for readers to many of the works available in English by Patrul Rinpoche.

Foundations

The Foundations: Ngöndro

The Words of My Perfect Teacher, or Kunzang Lama'i Shelung, must be one of the most influential works to come out of Tibet. For westerners, the translations, first by Sonam Kazi and then later by the Padmakara Translation Group, have been instrumental in our Buddhist education. In this work Patrul Rinpoche puts to paper a long oral tradition on the preliminary or foundational practices, from the Four Thoughts that turn the mind to Dharma to refuge, bodhicitta, mandala offerings, purification relying on Vajrasattva, and Guru Yoga. It is full of stories that drive the points home in a way that go right to the reader's heart. Lamas have said that this book has a particular quality that rereading it nearly always gives the reader a new discovery. And revisiting it again and again is how it is meant to be used—this is not a work to check the box that you have read it, but for it to become part of the one studying it.

And to go even deeper with it, Kathog Khenpo Ngawang Pelzang, who received it in his youth from Patrul Rinpoche's heart disciple Lungtok Tenpai Nyima, wrote his Zintri, or notes, that form The Guide to the Words of My Perfect Teacher. This work presents the background for the teachings of the main work. For example Patrul Rinpoche's chapter on the Three Jewels corresponds to this work's in-depth exposition on the finer points of the Three Jewels and Patrul Rinpoche's chapter on the mandala offering is complemented by Khenpo's chapter on Buddhist cosmology. Together these two works provide a multi-faceted overview of how to practice.

The Mahayana

While Patrul Rinpoche is famed as a Dzogchen yogi, at the core of his practice was the Mahayana ideal of the bodhisattva, a path he truly lived. It is said that Patrul Rinpoche traveled alone, carrying two texts with him. The first was The Way of the Bodhisattva. The second was Nagarjuna's Root Stanzas of the Middle Way.

The Nectar of Manjusri's Speech: A Detailed Commentary on Shantideva's Way of the Bodhisattva

by Khenpo Kunzang Pelden, based on Patrul Rinpoche's teachings

While Patrul Rinpoche did not compose a work on the Way of the Bodhisattva, he taught it constantly, over one hundred times from beginning to end. It had fallen into disuse outside a few monastic centers, and it is thanks to Patrul Rinpoche this text became integral to all the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Luckily for us, one of his most dedicated students, Khenpo Kunzang Pelden or Khenpo Kunpel, compiled these teachings he received from Patrul Rinpoche and composed The Nectar of Manjusri's Speech: A Detailed Commentary on Shantideva's Way of the Bodhisattva.

The Wisdom Chapter

by Mipham Rinpoche, based on teachings he received from Patrul Rinpoche

Patrul Rinpoche, also imparted teachings to Mipham Rinpoche, who based his understanding on these when he wrote his commentary on the famous (and famously challenging) ninth chapter of The Way of the Bodhisattva, now translated as The Wisdom Chapter.

Groundless Paths: The Prajnaparamita Sutras, The Ornament of Clear Realization, and Its Commentaries in the Tibetan Nyingma Tradition

by Karl Brunnholzl, with extensive translations and analysis of Patrul Rinpoche's work

On the Abhisamayālaṃkāra, one of the Five Maitreya Texts imparted to Asanga by Maitreya himself, Patrul Rinpoche wrote seven texts, the main two of which are The General Topics on the Abhisamayālaṃkāra and A Word Commentary on the Abhisamayālaṃkāra. What will be surprising for some, the bulk of these two works are, in the honored Tibetan tradition of honoring the words of past masters, is almost entirely excerpts from Tsongkhapa's commentary on the text, The Golden Garland of Explanations.

A distillation (if a 900 page work can be called that) of Patrul Rinpoche's works on this text, are what forms the bulk of Groundless Paths: The Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras, The Ornament of Clear Realization, and Its Commentaries in the Tibetan Nyingma Tradition

Watch scholar and translator Karl Brunnholzl discuss the trilogy of commentaries on Prajaparamita, of which Groundless Paths, heavily focused on Patrul Rinpoche, is the third volume.

The Speech Virtuous in the Beginning, Middle, and End

The Speech Virtuous in the Beginning, Middle, and End, one of the most influential works of Patrul Rinpoche, is included is included in whole or in part in several books. Patrul Rinpoche wrote this while staying in a remote cave not far from the Tibetan-Chinese border. In this work, be pulls the rug from under our normal way of being, so full of deceit and hypocrisy. He concludes that only by turning away from an ordinary life and pursuing the path of Buddhism. He then outlines the preliminary practices, the development and completion stages of tantric practice, and finally the practices of Mahamudra and Dzogchen. This text is full of the wisdom, humor, and directness that characterize all of Patrul Rinpoche's works, but it is unique in that it is meant to be memorized, making its message easy to bring right into our hearts.

The Heart Treasure of the Enlightened Ones

The Practice of View, Meditation, and Action

A commentary on Patrul Rinpoche's teachings by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche

In the accompanying commentary to Patrul Rinpoche's root text, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910–1991)—lineage holder of the Nyingma school and one of the great expounders of the Dharma in Europe and North America—expands upon the text with his characteristic compassion and uncompromising thoroughness. Patrul Rinpoche's fresh and piercing verses combined with Khyentse Rinpoche's down-to-earth comments offer a concise yet complete examination of the Buddhist path.

Sunlight Speech That Dispels the Darkness of Doubt

Sublime Prayers, Praises, and Practices of the Nyingma Masters

Trasnlated by Thinley Norbu Rinpoche

Another superb translation of the root text of Patrul Rinpoche's The Practice of the View, Meditation, and Action, Called “The Sublime Heart Jewel”, The Speech Virtuous in the Beginning, Middle, and End is included in Thinley Norbu Rinpoche's collection of translations entitled Sunlight Speech That Dispels the Darkness of Doubt. This text presents advice to practitioners on the path to enlightenment, which is all contained in the three aspects of the correct view, meditation, and action, synthesized in the practice of the Six-Syllable Mantra of Avalokiteshvara.

Two poems of Patrul Rinpoche are included in what in the mind of your author here is one of the most extraordinary anthologies of Tibetan Buddhism: Straight from the Heart: Buddhist Pith Instructions.

The first poem is an excerpt from Speech That Is Virtuous (see the entry from Sunlight Speech in this article) and the translator has titled it Afflictions Are Wisdom, the Skandhas Are Avalokitesvara. The second is The Crucial Point of Practice.

Sole Panacea

A Brief Commentary on the Seven-Line Prayer to Guru Rinpoche That Cures the Suffering of the Sickness of Karma and Defilement

by Thinley Norbu Rinpoche

Thinley Norbu Rinpoche also quotes this at length in Sole Panacea: A Brief Commentary on the Seven-Line Prayer to Guru Rinpoche That Cures the Suffering of the Sickness of Karma and Defilement.

Tantra

Patrul Rinpoche wrote multiple works on tantric practice, several of which have been translated into English.

Deity, Mantra, and Wisdom

Development Stage Meditation in Tibetan Buddhist Tantra

by Patrul Rinpoche, Jigme Lingpa, and Getse Mahapandita Tsewang Chokdrub

Patrul Rinpoche wrote two extremely helpful texts on generation stage practice which are included in Deity, Mantra, and Wisdom.

The first is Clarifying the Difficult Points in the Development Stage and Deity Yoga and is meant to be a companion piece to Jigme Lingpa's Ladder to Akanishta which accompanies it in this volume. As the translators explain, "Expanding on the presentation given in Ladder to Akaniṣṭha, he highlights some of the more obscure issues addressed by Jigme Lingpa and clarifies the latter’s presentation. In addition to his clarification of difficult issues, Patrul also stresses the importance of compassion and the view of emptiness in the context of tantric practice."

The second text by Patrul Rinpoche in this volume is The Melody of Brahma Reveling in the Three Realms: Key Points for Meditating on The Four Stakes That Bind the Life-Force. These Four Stakes are absorption, essence mantra, unchanging realization, and projection and absorption. Patrul Rinpoche lists they key points associated with each of the four. Together, they form an essential framework in development stage practice according to the Nyingma tradition.

Hear Dharmachakra Translation Committee member Andreas Doctor discuss this book, its background and their teacher Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche's encouragement to bring this important work to a western readership.

The Gathering of Vidyadharas

Text and Commentaries on the Rigdzin Düpa

By Jigme Lingpa, Patrul Rinpoche, Khenpo Chemchok, Kangsar Tenpe Wangchuk, and Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Gyurme Avertin

These Four Stakes discussed above, central as they are to the Nyingma tradition, are unsurprisingly essential in the Lonchen Nyingtik lineage. The the main lama practice is the Rigdzin Düpa, or Gathering of the Vidydharas, a practice centered on Guru Rinpoche Padmasmbhava and other awareness holders. One of the translations of this volume is by Khangsar Tenpe Wangchuk which is a commentary on Patrul Rinpoche's Melody of Brhama discussed above, and Padmasambhava'a Garland of Views.

The following text in the volume is a short one authored by Patrul Rinpoche himself, and is titled A Clearly Reflecting Mirror: Chöpön Activities for the Rigdzin Düpa, the Inner Sadhana of the Longchen Nyingtik Cycle. This is a ritual manual for a multi-day drupchö intensive practice. It covers arranging the mandala, the Rigdzin Düpa torma, Fulfillment-and-Confession torma, the Dharmapala tormas, additional offerings, various offering activities for the attendants, tsok, remainders, Dharmapala practice, the horse dance, offerings, and prayers for auspiciousness.

Hear Matthieu Ricard discuss Patrul Rinpoche's advice on meditative progress and experiences

Dzogchen, the Great Perfection

All of Patrul Rinpoche's works regardless of the subject are imbued with the view of Dzogchen. However, he authored many works explicitly on this system of practice.

Primordial Purity

Oral Instructions on the Three Words That Strike the Vital Point

By Patrul Rinpoche and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche

One of Patrul Rinpoche's most famous Dzogchen texts is The Three Words That Strike the Vital Point, itself based on a short work by the early Dzogchen master Garab Dorje which he had imparted to Manjusrimitra. This text, along with a commentary by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche is included in Primordial Purity. This work is an overview of the view, meditation, and action of Dzogchen. As Khyentse Rinpoche explains, these are not ordinary teaching:

"If you practice accordingly, you cannot help but be liberated. It will not be enough, however, just to practice for one or two days. In such a short time, we cannot break through our confusion. Even though you cannot spend your whole life continuously practicing in solitary retreat, please do as much practice as you can every day. As it is said, 'A collection of drops can become an ocean.' Since the teaching becomes more and more profound through continuous practice, confusion will naturally be purified, and all good qualities will spontaneously unfold. Those are the key instructions of the gurus of the three lineages."

The Nature of Mind

The Dzogchen Instructions of Aro Yeshe Jungne

by Patrul Rinpoche, Khenpo Palden Sherab, and Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal

The Nature of Mind: The Dzogchen Instructions of Aro Yeshe Jungne is a commentary on a fascinating text by Patrul Rinpoche by the Khenpo brothers Palden Sherab and Tsewang Dongyal. It is centered around a translation of Patrul Rinpoche's Clear Elucidation of True Nature: An Esoteric Instruction on the Sublime Approach of Ati. This text Patrul put together to encapsulate all the teachings from the Aro tradition in a single short text. It is a pithy guide to discovering the nature of your own mind and gives explicit instructions on how to do so for those of us of superior, middling, and lesser capabilities. It is superb.

Beyond the Ordinary Mind

Dzogchen, Rimé, and the Path of Perfect Wisdom

Translated by Adam Pearcey

Beyond the Ordinary Mind, an extraordinary collection of profound advice on Dzogchen from many great masters, compiled and translated Adam Pearcey, the force behind Lotsawa House. The piece by Patrul Rinpoche is called Uniting Outer and Inner Solitude: Advice for Alak Dongak Gyatso. Alak Dongak Gyatso was a student of Patrul Rinpoche and Pearcey tells a few stories about this somewhat elusive figure who was on the losing end of the stick in a debate with Mipham Rinpoche and writes that this work,

"is more than just a poem of advice on the importance of remaining in solitude. It offers Patrul Rinpoche’s views on a subject close to his own heart: he spent most of his life in retreat and even wrote this text while residing in 'the mountain solitude of Dhichung.' But it is also one of the few surviving textual clues to the mysterious life of Alak Dongak. And if we read it as a moving attempt to console a dear but despondent disciple, then it has a further dimension, as an encouragement to respond to an ordinary human situation by transcending ordinary human limitations."

The Golden Letters

The Tibetan Teachings of Garab Dorje, First Dzogchen Master

by Garab Dorje, translated by John Myrdhin Reynolds

The Golden Letters: The Tibetan Teachings of Garab Dorje, First Dzogchen Master includes a work by Patrul Rinpoche entitled The Special Teaching of the Wise and Glorious King, a four page poem followed by a more extensive auto-commentary.

Dzogchen

Heart Essence of the Great Perfection

by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

His Holiness teaches on Patrul Rinpoche's commentary to Garab Dorje's famous Three Words That Strike the Vital Point, also using other texts such as Longchenpa's Cho Ying Dzod, or Treasury of Dharmadhatu. His Holiness says,

Fundamentally, no matter who we are, whether we meditate or not, the self-arising wisdom of rigpa is already primordially present, and we have never strayed from it. Then there is rigpa as it is directly introduced to us by a master, on the basis of our personal practice. The nature of rigpa in both cases is identical—it is uncontrived rigpa—but in the one case it is simply so, without having been directly introduced, while in the other case we are recognizing our true nature for what it is. So one can talk about rigpa in two ways. But actually, there are not two things, one reuniting and another being reunited. The direct introduction to what is naturally present as the ground of being is metaphorically called “reuniting mother and child.

Mudra: Early Poems and Songs

by Chogyam Trungpa

The first section of this book is a translation of a four page poem by Patrul Rinpoche addresses to the adept Abushri. It is a beautiful piece of advice that cannot fail to move the reader.

Patrul Rinpoche wrote a short work called Chase Them Away! which was translated by Herbert Guenther. This is included in the anthology The Buddha and His Teachings. It appears this work was written when he was an old man as it is a reflection of his life, looking back and telling us "like it is". It reflects the wisdom from a life dedicated to practice and benefiting others. Here is one of the verses:

Chase Them Away!

When first I saw wealth,

I had the feeling of momentary joy

Like a child gathering flowers:

That's what is meant by not hoarding riches and wealth.

When later I saw wealth,

I had the feeling of there never being enough

Like water being poured into a pot with a broken bottom:

That's what is meant by making small efforts to gain something.

When now I see wealth,

I have the feeling of its being a heavy burden

Like an old beggar with too many children:

That's what is meant by rejoicing in having nothing.

Additional Resources

There are three excellent sources for more on Patrul Rinpoche.

![]() The Treasury of Lives also has a biography of Patrul Rinpoche among its collection of Tibetan figures.

The Treasury of Lives also has a biography of Patrul Rinpoche among its collection of Tibetan figures.

And for Tibetan readers, TBRC/BDRC of course provides downloadable pdfs of Patrul Rinpoche's works in Tibetan.

The Teachers of Pema Chodron: A Reader's Guide

Pema Chödrön refers to many of her teachers and friends in her latest book Welcoming the Unwelcome. For fans of Ani Pema who might be less familiar with some of these figures but want to hear more from her main inspirations, teachers, and role models, this is for you! For those who listened to the audiobook of Welcoming, hearing the narrator and actress Claire Foy pronounce so many masters of Buddhism was a thrill.

Pema Chödrön refers to many of her teachers and friends in her latest book Welcoming the Unwelcome. For fans of Ani Pema who might be less familiar with some of these figures but want to hear more from her main inspirations, teachers, and role models, this is for you! For those who listened to the audiobook of Welcoming, hearing the narrator and actress Claire Foy pronounce so many masters of Buddhism was a thrill.

Buddhist Teachers of Pema Chodron from Long Ago

Some of the most beloved figures and their writings come from the early history of Buddhism in India and Tibet.

Shantideva

She writes, “I often quote Shantideva, a great Buddhist sage from the eighth century whose writings are widely taught to this day. His advice to keep ourselves from escalating is to ‘remain like a log of wood.’ He lists many provocative situations and then recommends that we don’t act or speak when they come up. Often people interpret this advice as repression. But the point is that remaining like a log interrupts the momentum of our habitual reactions, which usually make things worse. Instead of reacting, we rest with the moving, heightened energy that has arisen. We let ourselves just experience what we’re experiencing. This slows down the process and allows some space to open up. It gives us a chance to discern our inner process and then do something different.”

The best way to explore this is reading the original, then Pema’s commentary Becoming Bodhisattvas, and then looking into it further through our Reader’s Guide on The Way of the Bodhisattva.

Machik Labdron

“Machik Labdron, a great Tibetan practitioner who lived in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, had a list of radical suggestions for getting unstuck from our ego-clinging. The first of these is ‘Reveal your hidden faults.’ Instead of concealing our flaws and being defensive when they are exposed, she counseled us to be open about them.”

We have a dedicated page on Chod that presents the dozens of books, articles, and videos on Machik and the practice of Chod. Some of these are pretty advanced, but two great places to start are Machig Labdron and the Foundations of Chod and Tsultrim Allione’s Women of Wisdom.

Thogme Zangpo

Thogme Zangpo, the beloved fourteenth-century Tibetan master is mentioned a dozen times in Welcoming the Unwelcome (and mentioned in over 120 other Shambhala books), and Ani Pema devotes an entire online course to his classic work called The Heart of the Matter.

She says, “In the fourteenth century, the Tibetan sage Thogme Zangpo wrote The Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva, which is still one of the most quoted and beloved poems in Buddhist literature. Each of its stanzas gives advice on how to live like a bodhisattva, a person whose highest aspiration in life is to wake up for the benefit of all living beings. In one verse, he poignantly describes why a comfort-oriented lifestyle is unsatisfactory. Happiness ‘disappears in a moment,’ he says, ‘like a dewdrop on a blade of grass.’ Basing your comfort on things that don’t last is a futile strategy for living. Even when you get something you’ve always wanted, the pleasure you get lasts for such a short time.”

Thogme Zangpo’s Thirty-Seven Practices is a classic and translations of it appear in all the contemporary explanations on it. In addition to Ken McLeod’s translation that she mentions, there is an extraordinary explanation of this work by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (more on him below) called Heart of Compassion, available in both book and audio. There are also other excellent explorations of this work from Thubten Chodron and Geshe Sonam Rinchen.

For all the books, videos, and articles on this work, see our dedicated page to the 37 Practices of the Bodhisattva.

Longchenpa

The fourteenth-century master Longchenpa, or Longchen Rabjam, is one of the pillars of Tibetan Buddhism.

The fourteenth-century master Longchenpa, or Longchen Rabjam, is one of the pillars of Tibetan Buddhism.

“The great fourteenth-century yogi Longchenpa said that how we label things is how they appear to be. I decided to experiment with this teaching and see how it applied to my obsession with cleanliness."

Here is the full story from the audiobook read by Claire Foy:

Much of Longchenpa’s writings are for those who have been immersed in Tibetan Buddhist practice and study for a long time, but two excellent starting places are his biography and the first volume of his “Trilogy of Rest”.

The Direct Teachers of Pema Chodron

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche

“Trungpa Rinpoche said that the way to arouse bodhichitta was to “begin with a broken heart.” Protecting ourselves from pain—our own and that of others—has never worked. Everybody wants to be free from their suffering, but the majority of us go about it in ways that only make things worse. Shielding ourselves from the vulnerability of all living beings—which includes our own vulnerability—cuts us off from the full experience of life. Our world shrinks. When our main goals are to gain comfort and avoid discomfort, we begin to feel disconnected from, and even threatened by, others. We enclose ourselves in a mesh of fear. And when many people and countries engage in this kind of approach, the result is a messy global situation with lots of pain and conflict.”

The best place to start exploring his teaching is our Reader’s Guide to his works, which include general introductions to meditation, mindfulness, the various traditions of Buddhism, art & poetry, the secular Shambhala teachings, death & dying, and more.

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche is Ani Pema’s current teacher, and she spends much of her time in retreat under his direction. He is based in Colorado, but teaches all over the world.

Unsurprisingly he appears in many of her books, especially the more recent ones. In Welcoming, she writes, “if we get to a point where hardships bring out the best in us, we will be of great help to those in whom hardships bring out the worst. If even a small number of people become peaceful warriors in this way, that group will be able to help many others just by their example. Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche is an advocate of this kind of courageous and practical realism. He urges people to train in becoming ‘modern-day bodhisattvas,’ or simply ‘MDBs.’ His students have even designed an MDB baseball cap to inspire themselves and others to move through the world with an altruistic, resilient heart. This work is based on getting to know how things really are and conducting ourselves bravely and creatively within that framework.”

Here she is discussing his recent book, Training in Tenderness.

Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

We recently published this Reader’s Guide to the works of Thrangu Rinpoche, which will give you great ideas on where to get started with this incredible teacher. Here is Pema Chödron telling a story about him in Welcoming the Unwelcome (audiobook read by Claire Foy):

$18.95 - Paperback

By: Khenchen Thrangu & Thrangu Dharmakara Translation Collaborative

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, who passed away in 1991, was a teacher to an entire generation of lamas, monastics, and lay people from His Holiness the Dalai Lama to nomads in the wilds of Tibet. He was a very important teacher to both Trungpa Rinpoche and Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche.

Ani Pema relates, “Trungpa Rinpoche told this story about how he once was sitting in a garden with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of his most important teachers. They were just enjoying their time together in the beautiful setting, hardly saying anything, simply happy to be there with each other. Then Khyentse Rinpoche pointed and said, ‘They call that a “tree,”’ and both of them roared with laughter. For me this is a wonderful illustration of the freedom and enjoyment that await us when we stop being fooled by our labels. The two enlightened teachers thought it was a riot that this complex, changing phenomenon, with all its leaves and bark and fragrance, could be thought of merely as a ‘tree.’ As our labels loosen their grip on us, we too will start to experience our world in this lighter, more magical way.”

The story of Khyentse Rinpoche’s life is an amazing tale of dedication, disciple, and devotion and is beautifully told in Brilliant Moon, a combined autobiography and biography, with accounts of him from across the Buddhist world including, Her Majesty the Royal Grandmother of Bhutan, and many of the great masters of the last century. We also have a Reader’s Guide to his works, which are some of the most beloved works we have in print.

Here is Richard Gere, the Dalai Lama, and Mattheu Ricard reflecting on this extraordinary teacher:

$39.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche & Ani Jinba Palmo & Shechen Rabjam

The Heart Treasure of the Enlightened Ones

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche & Padmakara Translation Group & Patrul Rinpoche

More Teachers and Friends

Tulku Thondup

“How do we adopt this counterintuitive attitude when our emotions and neuroses hit us hard, in the painful, nontheoretical way that they do? I have learned a few effective methods, two of which I will share here.

The first method is based on a teaching by Tulku Thondup Rinpoche. When any unwanted feeling comes up, the first step is to feel it as fully as you can at the present moment. In other words, hold the rawness of vulnerability in your heart. Breathe with it, allow it to touch you, to inhabit you—open to it as fully as you currently can. Then make that feeling even stronger, even more intense. Do this in any way that works for you—in any way that makes the feeling stronger and more solid. Do this until the feeling becomes so heavy you could hold it in your hand. At that point, grab the feeling. And then just let it go. Let it float where it will, like a balloon, anywhere in the vast realm of empty space. Let it float out and out into the universe, dispersing into smaller and smaller particles, which become inconceivably tiny and distant.”

Tulku Thondup’s The Heart of Unconditional Loveand The Healing Power of Mind are two excellent starting places to explore Tulku Rinpoche’s extraordinary gift for opening our hearts.

Anam Thubten

Anam Thubten

Ani Pema writes, “Anam Thubten emphasizes that this brave acknowledgment of our ‘flaws’ is not about indulging in feelings of shame or guilt. It is, instead, about ‘not hiding anything from one’s awareness.’ Instead of reacting in one way or another, we can simply choose not to hide anything from our own mind. We can regard all that we observe simply as karmic seeds ripening. Whatever arises in our mind and heart is just our current experience, nothing more or less. Even our good and bad qualities are temporary and insubstantial, not ultimate proofs of our worthiness or unworthiness. They are not inherent to our fundamental nature of basic goodness; they are simply what is. If we learn to work with our experiences in this way, then instead of succumbing to the pull of our old habits, we can stay present with them until they calm down of their own accord.”

His books include No Self, No Problem, Embracing Each Moment, and his latest, Choosing Compassion.

Suzuki Roshi

Ani Pema shares this in Welcoming: “As the Zen teacher Suzuki Roshi famously said, ‘In the beginner’s mind, there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s, there are few.’”

This quote comes from the best selling Zen book of all time, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind. Many other anecdotes and sayings of this remarkable teacher can be found in Zen is Right Here.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama

“When His Holiness the Dalai Lama started meeting with Buddhist teachers from the West, they would tell him how their students often expressed self-denigration. Even the teachers often had negative views of themselves. For the Dalai Lama, at first, these words just didn’t compute. Having a bad self-image was completely alien to how he saw himself and others. It was so far away from the open-ended and basically good nature that he knew everyone possessed. It didn’t make sense that people could be so hard on themselves, so judgmental—even to the point of self-hatred.”

Ani Pema goes on to unpack this and show the path forward to the reader.

Here is a Reader’s Guide to over two dozen of the Dalai Lama’s works, including The Core Teachings of the Dalai Lama series.

Bernie Glassman

From Kanzeon Zen Center via Wikipedia

Pema writes, “Roshi Bernie Glassman, who spent decades working with homeless people in Yonkers, New York, said ‘I don’t really believe there’s going to be an end to homelessness, but I go in every day as if it’s possible. And then I work individual by individual.’”

Glassman, who passed away in 2019. was a huge figure in the American Buddhist world. He was known for his iconoclastic style and enormous heart, dedicating his life to helping others with cigar perched firmly in his mouth, whether in his collaboration with Jeff Bridges or helping homeless on the streets.

Here are two of his books

Instructions to the Cook describes the innovative business model Roshi Bernie Glassman developed to revitalize a poverty-stricken section of Yonkers, New York. Using his own story as a base, Glassman shows how social engagement can be used as a spiritual practice to promote both personal and societal transformation.

His book Infinite Circle covers three core Zen concepts and how they relate to his community development organizations and the Zen Peacemaker Order.

Matthieu Ricard

Ani Pema, when discussing the practice of tonglen, says, “Matthieu Ricard, the well-known Buddhist monk and author, was once being tested for compassion by being hooked up to one of those big machines that records all your brain activity. He began by visualizing himself sending rays of healing light to those who are suffering, but the scientists wanted him instead to focus on breathing the suffering in. For that period, he saturated himself. He had just visited an orphanage in Romania where it was so sad to see how the children were being treated. And he’d also recently been in Tibet after an earthquake. So he had a lot of material, which he kept breathing in and breathing in.

From this experience, he said he learned that a person can only take so much. He found that taking on suffering had to be balanced with love and kindness, with the completeness of life. I think that this example illustrates how he approached the excessive risk zone, and realized that if you breathe in the pain, you also have to send out the love. There’s a sense of connecting with both beauty and tragedy—with the delightfulness and upliftedness of life, and with the degraded and cruel part of life.”

He has written books on animal ethics, collections of stories and wisdom from many great masters, and translations of some very important autobiography and biographies.

Ken McLeod

In Welcoming the Unwelcome, Ani Pema wrote, "my friend Ken McLeod wrote Reflections on Silver River, a book that has deepened my understanding of the bodhisattva path considerably".

This book is a translation of and commentary on the 37 Practices of the Bodhisattva, by Thogme Zangpo (see above). She often points to McLeod's book as a superb in her teachings.

He has also translated an incredible text: The Great Path of Awakening: The Classic Guide to Lojong, a Tibetan Buddhist Practice for Cultivating the Heart of Compassion. Here he is discussing that work:

In Closing

We hope this article gives you some great ways to go deeper with many of Pema Chödrön’s main inspirations.

Books by Pema Chödrön

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

The Dalai Lama on Questions Concerning the Lack of Intrinsic Existence

The following article is an excerpt adapted from

HH the Dalai Lama understands that questions (or “qualms”) naturally arise for students as they think about key Buddhist tenets. In this adaptation from his book Transcendent Wisdom (now published as Perfecting Wisdom)—translated and edited by B. Alan Wallace—he brings up qualms and gives his responses about what it means for things to be real or not real.

Qualm: If it is an error to think of form and so forth as real, how can it be that we verifiably perceive them? What further criterion beyond verifying perception is needed to establish the true existence of entities?

Response: Such entities are indeed verifiably perceived. However, when we say “verifying cognition” this suggests infallibility. It is a non-deceptive awareness with reference to the appearance of a self-defining object. Realists—those who assert true existence—have just this in mind when speaking of verifying cognition. They believe that phenomena appear just as they exist, and they appear to be truly existent. They call a cognition that is non-deceptive with regard to that appearance “verifying.”

Now in the Centrist context, infallible cognition is acknowledged, while denying that there is any such thing as even conventional intrinsic existence. Such cognition is said to be deceptive with regard to the appearance of phenomena as intrinsically existent. The Prasangikas, who hold this view, do not accept verifying cognition with respect to such appearance. Thus, they allow that a deceptive awareness may nevertheless verify its object. Therefore, phenomena exist by the power of consensus, not by their own intrinsic reality.

Such phenomena as form are regarded as misleading, for their mode of appearance and their mode of existence are not in accord with each other. Common people regard impure objects as pure, for the way those objects appear belies the way they actually exist. Although they are thought by consensus to be pure, that conviction is false. Likewise, although phenomena are not truly existent, they appear as if they were; and thus they are asserted to be misleading.

Qualm: The Lord Buddha is recorded in the scriptures as saying that all composites are impermanent and all tainted things are unsatisfactory. Thus, when the Buddha taught the Four Noble Truths, he spoke of sixteen attributes, including impermanence. Are those not ultimate truths; are they not absolute?

Response: The Buddha taught these in order for people to enter into the experience of emptiness; but ultimately speaking, there is no such thing as the impermanence of a pot. Ultimately, events are not momentary. Ultimately, the object itself does not exist, so it has no properties such as impermanence.

Qualm: If one takes the position that ultimately events are not of a momentary nature, does that mean that the conventional presentation of phenomena as passing away moment by moment is incorrect?

Response: No, that is not incorrect. That momentary nature is established by conventionally verifying cognition, so we accept that on a conventional basis. All the sixteen attributes of the Four Noble Truths are conventionally realized by contemplatives, so we can accept them.

Qualm: Well then, can we not call those sixteen “reality”?

Response: Common people mistake things that are essentially impermanent as permanent, and impure things as pure. In comparison to such attitudes, the contemplative experiences reality. It is conventional reality.

Qualm: If you deny true existence, do you still assert that one accumulates merit by making offerings to Awakened Beings and so on?

Response: Yes. One engages in illusion-like actions, and illusion-like fruits of those actions ensue. For example, Realists, who assert true existence, maintain that from real actions, real merit is accumulated and real results are experienced. The Centrists acknowledge the accumulation of merit and the effects of actions but as not truly existent.

Qualm: If sentient beings are like illusions, how can they take birth again after having died?

Response: An illusion is not truly existent. If an illusion appears as a horse or elephant, it does not exist as such. Although it is not real, it appears due to a complex of conditions, and it vanishes due to the cessation of that complex of conditions. So even an illusion depends upon causes and conditions. One cannot establish duration as a criterion for true existence.

Books by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama's Favorite Meditation

The Dalai Lama is particularly fond of a meditation that promotes taking responsibility for others’ well-being. Based on A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life by the eighth-century Indian scholar yogi-poet Shantideva, he calls for imagining a three-sided scene. In meditation:

The Dalai Lama is particularly fond of a meditation that promotes taking responsibility for others’ well-being. Based on A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life by the eighth-century Indian scholar yogi-poet Shantideva, he calls for imagining a three-sided scene. In meditation:

1. Imagine that you are your better, more relaxed, confident, and wise

self in the middle looking at two sides in front of you to your left

and right.

2. Then imagine your selfish self on one side: the person who, in a

pushy way, is trying to get an earlier flight, or a piece of cake, or

something like that—this person who’s just thinking of herself or

himself. Remember a recent incident or play-act a convincing

instance of your nasty, cruddy self, thinking, “I, I, I,” not your usual self,

but a nasty, self-serving version.

3. Across from your selfish self imagine a group of destitute persons—

poverty-stricken or in pain.

Thus, in the middle looking at the other two sides is your wise, discriminating self. You look out to one side where your cruddy, selfish self is, utilizing any of a variety of examples:

1. Remember an incident when you were whining in self-pity about your own welfare, putting yourself

totally, unreasonably ahead of everyone else. You were so wound up in your own thing that you

couldn’t notice somebody else’s concern. It’s awful. It’s ugly.

2. Or, remember a situation when you unreasonably carried on, got angry.

3. Or, remember an instance of feeling selfish desire: You’re in a store somewhere, you particularly

want some item, you’re getting overly fascinated with it.

4. Or, remember a time when you were greedily jealous. There’s always someone among your

acquaintances who makes more money for less work.

Then, on the other side, look at the group of destitute people. Sick. Living in poverty. Finding it difficult to get something to eat.

His Holiness asks the level-headed you in the middle to reflect on this fact: “The selfish I on one side and the destitute ones on the other side equally want happiness and don’t want suffering.” And then the question is: Whom will I help? My selfish self, or the destitute people? Just imagine it. As the wise one, you are asking yourself, “Which side am I going to help: the selfish one, groveling after her or his own welfare, or these destitute people?”

The only conclusion is: “There’s only one of me; others are infinite in number, exemplified by five or ten destitute people. How could the welfare of this infinitely larger group not be more important?”

In other circumstances, outside of such a graphic situation, it might seem that, in the abstract, self and other are equal: Self is one and other is one. They’re both singular. But when, aided by this visualization, you actually consider what “other” is, it’s composed of an incredible number of individual selves, individual I’s.

But still, you might consider that, even in this scenario, you assume that the motivations of the “other” side could be just as self-cherishing as your own, and thus you could find no real qualitative difference between self and other. You might then be inclined to help all equally—including your own nasty, self-cherishing self. It strikes me that this is perfectly fine, as long as your nasty self amounts to just one and does not equal “other” in terms of number, who, quantitatively, are hugely different. Thus, if you are considering five people on the “other” side, then you should consider yourself one-sixth, not half.

Or, you might get stuck wondering whether this contemplation calls for helping others and not helping yourself at all. It seems to me that the win-win solution is to put the main emphasis on helping others, making altruism the motivation of self-improvement. What is being targeted here is the feeling of oneself being so exaggeratedly important in the process of becoming happy. Everyone wants happiness and doesn’t want suffering.

Or, you think, “I am more important because I’m figuring this all out, and I’ll be able to pass it on to ones who don’t understand.” I have found it fun to let this type of pride just be, not try to oppose it, but to think, “Even this sense of self-importance is for the sake of others.” Think this over and over again, and pride, which usually serves to hide your inadequacies, disappears. The self-importance becomes hollow and fades. When I was interpreting for the Dalai Lama under the bright lights in front of large crowds, I found the situation brought a huge uplift in concentration—the communication of his message at that point depended on me. I enjoyed the challenge, enjoyed making myself inconspicuous but effective, enjoyed trying to make the task look effortless, enjoyed the open state of mind that I would need for adequate memory when he would talk for five minutes in Tibetan without break, enjoyed the interaction with him when, listening to my English, he would then repeat in Tibetan something I had missed. But I found that after leaving the stage, I longed to be back on it—the lights, the intensity, the attention. I found that it was getting so that I lusted after “the stage.” I recalled stories of actors who could not stand themselves except when onstage and knew I had to figure a way out of this. After a while, this is what came to me: “May these feelings of intensity and so forth go for the benefit of those who are listening.” I thought this over and over, and it worked. I no longer lusted for the situation, but I accomplished this not by forcing myself to not want it, but by realizing that the whole activity was for the sake of others and by deeply feeling this realization in imagination—imagining strength entering into the bodies and minds of the audience. Any type of pride can be handled in the same way.

There are a lot of little things that we can do for others as we go about the day. Provide a cushion for somebody in your meditation group who has difficulty finding a cushion to sit on. Little actions mean a great deal to others. When the Dalai Lama visited the University of British Columbia, he had a meeting with the dean and a group of professors including an aged man who had come in just for this meeting with His Holiness. He was sitting down. When His Holiness entered the room, he tried to get up, although His Holiness was not very near. The fellow, a thin, very old man, was trying to get up to show his respect. All of us saw the great difficulty that he had getting up—such that he might fall down—and we felt in our hearts for him. However, the only one who moved quickly to help him was the Dalai Lama, who took hold of him and helped him up. His Holiness wasn’t so full of himself as to think, “I’m here to receive these people.”

So, it’s the little things that count in valuing others. Making a decision to look to see how we can most effectively help those around us. With such a motivation, your activities have a true importance that is not self-centered. It’s difficult to decide how much to give away, how much time to devote to others, but the basic motivation is clear enough, and it itself, on a day-to-day basis, unties a lot of problems.

From A Truthful Heart: Buddhist Practices for Connecting with Others by Jeffrey Hopkins

A Guide To the Bodhisattva Way of Life

| The following article is from the Winter, 1997 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life

By Shantideva

Translated by Vesna A. Wallace and B. Alan Wallace

In the whole of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition there is no single treatise more deeply revered or widely practiced than A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life. This authoritative translation by Vesna A. Wallace and B. Alan Wallace is the first English rendering of the original Sanskrit that also takes into .account the canonical Tibetan translation.

Please see the following chapter sample provided here for you.

Chapter III

Adopting the Spirit of Awakening

- I happily rejoice in the virtue of all sentient beings, which relieves the suffering of the miserable states of existence. May those who suffer dwell in happiness. (48)

- I rejoice in sentient beings' liberation from the suffering of the cycle of existence, and I rejoice in the Protectors' Bodhisattvahood and Buddhahood.

- I rejoice in the teachers' oceanic expressions of the Spirit of Awakening, which delight and benefit all sentient beings. (49)

- With folded hands I beseech the Fully Awakened Ones in all directions that they may kindle the light of Dharma for those who fall into suffering owing to confusion.

- Tibetan: "I happily rejoice in the virtue done by all sentient beings, which relieves the suffering of the miserable states of existence and in the well-being of those subject to suffering." This verse is followed in the Tibetan by an additional line, not found in the Sanskrit version, and is translated here in the following way: "I rejoice in the accumulated virtue that acts as a cause for enlightenment."

- Tibetan: "I happily rejoice in the oceanic virtue of cultivating the Spirit of Awakening, which delights and benefits all sentient beings."

- With folded hands I supplicate the Jinas who wish to leave for nirvana that they may stay for countless eons, and that this world may not remain in darkness.

- May the virtue that I have acquired by doing all this (50) relieve every suffering of sentient beings.

- May I be the medicine and the physician for the sick. May I be their nurse until their illness never recurs. (51)

- With showers of food and drink may I overcome the afflictions of hunger and thirst. May I become food and drink during times of famine.

- May I be an inexhaustible treasury for the destitute. With various forms of assistance may I remain in their presence.

- For the sake of accomplishing the welfare of all sentient beings, I freely give up my body, enjoyments, and all my virtues of the three times.

- Surrendering everything is nirvana, and my mind seeks nirvana. If I must surrender everything, it is better that I give it to sentient beings. (52)

- For the sake of all beings I have made this body pleasureless. Let them continually beat it, revile it, and cover it with filth. (53)

- Let them play with my body. Let them laugh at it and ridicule it. What does it matter to me? I have given my body to them. (54)

- The Panjika, p. 38: "Worship, disclosure of sin, rejoicing in virtue, etc."

- Tibetan: "For as long as beings are ill and until their illnesses are cured, may I be their physician and their medicine and their nurse."

- Tibetan: "As a result of surrendering everything, there is nirvana, [and] my mind seeks nirvana. Surrendering everything at once–this is the greatest gift to sentient beings."

- Tibetan: "I have already given this body to all beings for them to do with it what they like. So at any time they may kill it, revile it, or beat it as they wish."

- Tibetan: "Even if they play with my body, or use it as a source of jest or ridicule, since my body has already been given up, why should I hold it dear?"

- Let them have me perform deeds that are conducive to their happiness. (55) Whoever resorts to me, may it never be in vain.

- For those who have resorted to me and have an angry or unkind thought, may even that always be the cause for their accomplishing every goal. (56)

- May those who falsely accuse me, who harm me, and who ridicule me all partake of Awakening.

- May I be a protector for those who are without protectors, a guide for travelers, and a boat, a bridge, and a ship for those who wish to cross over.

- May I be a lamp for those who seek light, a bed for those who seek rest, and may I be a servant for all beings who desire a servant. (57)

- To all sentient beings may I be a wish-fulfilling gem, a vase of good fortune, an efficacious mantra, a great medication, a wishfulfilling tree, and a wish-granting cow.

- Just as earth and other elements are useful in various ways to innumerable sentient beings dwelling throughout infinite space, (58)

- So may I be in various ways a source of life for the sentient beings present throughout space until they are all liberated.

- Just as the Sugatas of old adopted the Spirit of Awakening, and just as they properly conformed to the practice of the Bodhisattvas,

- Tibetan: "Let them do anything that does not bring them harm. "

- Tibetan: "Whether they look at me with anger or admiration, may this always be a cause for their accomplishing all their goals."

- Tibetan: "May I be an island for those seeking an island, a lamp for those seeking light, a bed for those seeking repose, and a servant for all those beings desiring a servant."

- Tibetan: "Like the great elements such as earth and space, may I always serve as the basis of the various requisites of life for innumerable sentient beings."

B. Alan Wallace has authored, translated, edited, and contributed to more than forty books on Tibetan Buddhism, science, and culture. With fourteen years as a Buddhist monk, he earned a BA in physics and the philosophy of science and then a PhD in religious studies. After teaching in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he founded the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies to explore the integration of scientific approaches and contemplative methods.

Related Books

A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life

$16.95 - Paperback

$21.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Padmakara Translation Group

Beginninglessness of Consciousness: The Truth of Dependent Arising

| The following article is from the Winter, 1994 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

A Teardropin Chenrezig's Eye

Article written by Victoria Huckenpahler

His Holiness The Dalai Lama XIV, Tucson, AR circa de 1994

H.H. The Dalai Lama Gives a Five-Day Intensive Teaching on

Shantideva's Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life

Shantideva: The Patience Chapter

Against a vast panorama of blue sky punctuated by mountains not unlike those of his native Tibet, H.H. the Dalai Lama presented an intensive teaching on the Patience chapter of Shantideva's Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life. Dr. Howard C. Cutler, a Phoenix psychiatrist, Lopon Claude d'Estree, the Buddhist chaplain at the Univ. of Arizona, and Ken Bacher formed Arizona Teachings, Inc. to sponsor His Holiness' visit.

Words alone cannot do justice to the impact of this commentary on patience by one who has himself passed its harshest tests.

Analysis of the Anatomy of Anger

His Holiness began his commentary on Shantideva's text with an analysis of the anatomy of anger how it arises from a sense of injury, giving the illusion of acting as a protector in one's revenge. But because the harmful action has been completed, revenge cannot alter the situation. Indeed, it only complicates matters by causing the loss of physical health and mental peace, by destroying the virtue one has accumulated over eons, and by acting as a stumbling block to the bodhisattva vow. Proposing antidotes to anger which can be implemented in real life situations or in the imagination, His Holiness suggested that since anger is a part of our mind we can engage in a dialogue with it.

anger arises from a sense of injury, giving the illusion of acting as a protector in one's revenge. But because the harmful action has been completed, revenge cannot alter the situation.

The Development of Tolerance

He also counseled the development of tolerance, ranging all the way from the ability to endure minor physical inconvenience, such as poor weather, up to the high level tolerance of the Bodhisattva. If we learn to ignore small sufferings, we become sturdier in the face of larger troubles. Because suffering is a fact of life, it is a useful reminder of the fundamentally unsatisfactory nature of existence, which helps us develop a taste for renouncing samsara. Endurance of suffering must, however, be understood within the context of the Buddha's Third Noble Truth: the end of suffering. One endures to reach a state beyond suffering, otherwise the emphasis on stamina would be merely morbid.

suffering is a fact of life, it is a useful reminder of the fundamentally unsatisfactory nature of existence, which helps us develop a taste for renouncing samsara.

Why feel compassion toward an aggressor?

His Holiness cautioned that the cultivation of steadfastness did not imply that all situations should be accepted. Some circumstances require counter-measures, but even here one's principal concern is the well-being of one's opponent rather than personal gain. If, by not remarking on someone's ill deed one tacitly helps that person develop a negative habit, such passivity would constitute an infraction of the Bodhisattva vow. One is therefore sometimes bound, out of compassion, to take a strong stand. But why feel compassion toward an aggressor? His Holiness explained that it is because such a person is in the causal state of accumulating non-virtue, whereas oneself as victim has already experienced the ripening of negative karma.

Some circumstances require counter-measures, but even here one's principal concern is the well-being of one's opponent rather than personal gain.

His Holiness remarked that a disciplined mind is a religious mind, and far more indicative of a spiritual life than outer displays such as robes or shrines. He then elaborated on Shantideva's statement that people inflict harm without the consciousness of real choice. Rather, they are moved by negative emotions dependent on a collection of conditions. These conditions, in turn, have no choice or intention to produce a result. Thus, nothing has independent status or control over itself. If we examine the situation carefully we see that in many cases people harm themselves out of ignorance or carelessness. If this is so, how more easily can they visit the same on others? Thus we should respond with compassion, not anger.

people inflict harm without the consciousness of real choice.

Are afflictive emotions caused by habit?

A question arose as to whether afflictive emotions were caused by habit. The Dalai Lama responded that afflictions result from a continuum of conditioning which, within Buddhism, must be understood in the framework of reincarnation. In a single family each member is born with natural tendencies which are later enhanced by conditioning. These tendencies can only be attributed to the beginninglessness of consciousness. Here he likened the practice of Dharma to a surge suppressor because it helps stabilize our moods.

afflictions result from a continuum of conditioning which, within Buddhism, must be understood in the framework of reincarnation

How are we personally responsible when we experience anger?

The discussion progressed to personal responsibility involved in situations where we feel anger. If we are injured, we must reflect that it is our own karma which has attracted our misfortune. Further, it is our attachment to the body that has led us to acquire a material form whose nature is to feel pain. And once we accept the inevitability of pain within samsara, how greatly we suffer depends on how we respond to situations.

His Holiness laughingly remarked that whereas we are often hypersensitive about minor issues, we ignore major points having long-term consequences. He recalled the Tibetan saying, treat insults like wind behind your ear i.e., pretend you haven't heard a slight and in this way you protect yourself. He reiterated the truth of dependent arising, and how collections of conditions, rather than clear cut personal volition, usually lie behind injury. Citing the example of the Gulf War, he said: many people blame Saddam Hussein. That is not fair. I feel some kind of sympathy for him. He is a dictator and there are bad things, but without that powerful equipment his army couldn't function. All that equipment wasn't produced by itself! Many nations were involved.

Noting the human tendency to blame situations on external factors, exonerating oneself, he related this to the Tibetan situation. If we look at things the holistic way we cannot pinpoint one person. Much contribution was made by ourselves and the previous generation. It's not fair to blame everything on China.

once we accept the inevitability of pain within samsara, how greatly we suffer depends on how we respond to situations.

How does one practice altruism?