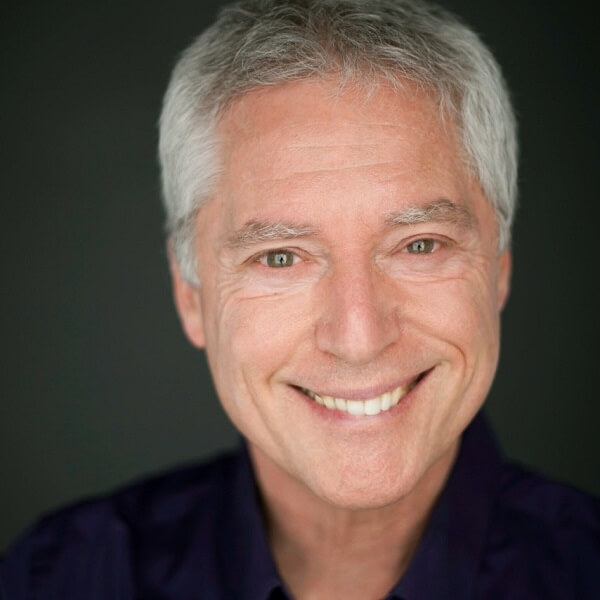

B. Alan Wallace

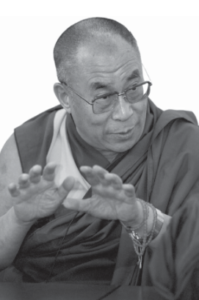

B. Alan Wallace has authored, translated, edited, and contributed to more than forty books on Tibetan Buddhism, science, and culture. With fourteen years as a Buddhist monk, he earned a BA in physics and the philosophy of science and then a PhD in religious studies. After teaching in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he founded the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies to explore the integration of scientific approaches and contemplative methods.

B. Alan Wallace

B. Alan Wallace has authored, translated, edited, and contributed to more than forty books on Tibetan Buddhism, science, and culture. With fourteen years as a Buddhist monk, he earned a BA in physics and the philosophy of science and then a PhD in religious studies. After teaching in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he founded the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies to explore the integration of scientific approaches and contemplative methods.

-

The Four Immeasurables

The Four ImmeasurablesBy B. Alan Wallace

Edited by Zara Houshmand

Read by Vanessa Kettering How to Practice Shamatha Meditation$21.95- Paperback

How to Practice Shamatha Meditation$21.95- PaperbackBy Gen Lamrimpa

Edited by Hart Sprager

Translated by B. Alan Wallace How to Realize Emptiness$27.95- Paperback

How to Realize Emptiness$27.95- PaperbackBy Gen Lamrimpa

Edited by Ellen Posman

Translated by B. Alan Wallace Meditation, Transformation, and Dream Yoga$24.95- Paperback

Meditation, Transformation, and Dream Yoga$24.95- PaperbackBy Gyatrul Rinpoche

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

Translated by Sangye Khandro Healing from the Source$26.95- Paperback

Healing from the Source$26.95- PaperbackBy Yeshi Dhonden

Edited by B. Alan Wallace

Translated by B. Alan Wallace Naked Awareness$34.95- Paperback

Naked Awareness$34.95- PaperbackBy Karma Chagme

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

Edited by B. Alan Wallace

Edited by Lindy Steele A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life$16.95- Paperback

A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life$16.95- PaperbackBy Shantideva

Translated by Vesna A. Wallace

Translated by B. Alan Wallace Calming the Mind$19.95- Paperback

Calming the Mind$19.95- PaperbackBy Gen Lamrimpa

Edited by Hart Sprager

Translated by B. Alan Wallaceper page

- Buddhism and Science 3item

- Buddhist Academic 1 item

- Buddhist History 1 item

- Buddhist Overviews 1 item

- Buddhist Philosophy 1 item

- Four Immeasurables 2item

- Four Noble Truths 1 item

- Introductions to Buddhism 4item

- Way of the Bodhisattva 1 item

- Bodhisattva Path 1 item

- Dream Yoga 2item

- Dzogchen 2item

- Kagyu Tradition 2item

- Lojong/Mind Training 3item

- Madhyamaka 1 item

- Mahamudra 2item

- Dudjom Tersar 1 item

- Nyingma Tradition 3item

- Shamatha 3item

- Stages of Meditation 3item

- Tibetan Medicine 1 item

- Workplace Mindfulness 1 item

- Ayurveda 1 item

GUIDES

Buddhist Mindfulness: A Guide for Readers

Today the term "mindfulness" has become a buzzword heard everywhere from elementary schools to corporate offices to the military. Generally speaking, when we use the term in secular life, we're referring to the ability to purposefully place our attention on our present experience whether it be walking step by step through a park, following our breath in and out or something more conventional like playing music or lifting weights. The purpose of mindfulness, in this regard, is about training one's attention.

However, while the practice of mindfulness has found its way into secular life, the roots of this Buddhist meditative practice stem far deeper, and the benefits of what we call "mindfulness" range beyond the common definition of "calming the mind" or "focusing on the present moment." In fact as Sarah Shaw points out in her book Mindfulness: Where It Comes From and What It Means, the Buddha used the Pali word sati rather than the Sanskrit term smṛti to describe mindfulness or satipaṭṭhāna. According to Shaw, the meaning of the term sati is significantly different from its Sanskrit correspondence which was more closely associated with the concept of memory rather than attention and awareness of the present moment. In this regard, Shaw notes that, the modern use of the term "mindfulness" is worthy of being understood as something far more complex and profound than simply "focused attention."

"...Buddhist understandings of psychology, of “living in the moment,” and of the benefits to be derived from this are more far-reaching than is suggested by many usages of the term mindfulness in the modern world."—Mindfulness, by Sarah Shaw

In this Guide for Readers, we'll showcase books such as Mindfulness, that delve into the historical texts, practices and applications of mindfulness from a Buddhist perspective in order to shed light on this extraordinary practice which has made headway in both religious and secular domains of modern life.

Mindfulness in the Pali Tradition

$17.95 - Paperback

Mindfulness: Where It Comes From and What It Means

By Sarah Shaw

As mentioned above, Mindfulness delves into the roots of the Buddhist practice of mindfulness from its origins in India to its spread across Asia and later into Europe and the United States. Shaw pays particular attention to the changing definition of "mindfulness," discussing both the origins of the Sanskrit term smṛti, and the Buddha's usage of the Pali term sati, as well as the etymology and biblical origins of the English term mindfulness. Her account is remarkably engaging and inspires readers to really consider the range of meaning behind this term which has become a part of everyday use.

In short, mindfulness incorporates both a sense of attentiveness and focus as well as a sense of memory and remembrance. However what is being remembered plays a large role in the context of each practice be it a Buddhist or secular activity. Through her research, Shaw takes her readers on an impressive journey through the history of mindfulness giving anyone interested in the practice a detailed map of "where it comes from," and perhaps even where it might go from here.

Crucially, she identifies how mindfulness cannot in fact be decoupled with an ethical dimension, a critique often levelled at mindfulness:

Mindfulness is one crucial part of a complete system of understanding the operation of the mind and the ways it can develop. So its nature is very different from its application in Western psychological models. Indeed, memory—the ancient Sanskrit meaning of the word—still plays an important part. Mindfulness is said always to work with other elements that support it and that it supports. Within the terms of Buddhist psychology, it simply cannot arise alone and likes company. When it arises, factors associated with it give it an ethical dimension, and other qualities arise too, such as loving kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. It is found in daily life and is also essential for deep meditations known as jhānas. It is also, again with other factors, a faculty that is said to bring liberating insight and to free the mind completely.

"A brilliant and precise introduction to the deep roots of mindfulness."

—Joan Halifax, author of Being with Dying

The Art of Listening: A Guide to the Early Teachings of Buddhism

By Sarah Shaw

In a similar vein to Mindfulness discussed above, The Art of Listening takes a look at the early teachings of the Buddha—specifically the Dīghanikāya or Long Discourses of the Buddha, one of the four major collections of teachings. In her introduction Shaw explains that as people become interested in Buddhism or Buddhist practices they are interested in understanding more about the suttas (Sk. sūtras). The Art of Listening was written for the purpose of guiding people to better understand the historical texts behind Buddhist thought and practice—and of course mindfulness plays a central role.

At the same time, she encourages readers to consider the historical context of suttas—namely the tradition of reading texts out loud, memorizing larges sections and passages, and of course, listening—all of which require the practice of mindfulness. She writes:

I have found taking one at a time, letting it sink in without rushing it, is the best way to become familiar with them. If you can arrange to have them read aloud to you, you are lucky! Reading them out loud to yourself is also a helpful way of letting them have their effect. It is worth remembering that for centuries and indeed now—they have been recited, as group performances, to perhaps a large number of listeners.

In this regard, Sarah Shaw combines a literary approach and a personal one, based on her experiences carefully studying, hearing, and chanting the texts. At once sophisticated and companionable, The Art of Listening will introduce you to the diversity and beauty of the early Buddhist suttas.

Translated by Gil Fronsdal

The Dhammapada is the probably the most widely read Buddhist scripture we have. Presenting two distinct goals for leading a spiritual life—attaining happiness in this life (and in future lives) and the achievement of absolute peace—this classic text of teaching verses from the earliest period of Buddhism in India conveys the philosophical and practical foundations of the Buddhist tradition.

In terms of mindfulness, the Dhammapada represents the core teachings of the Buddha. For centuries the verses in the Dhammapada were memorized and chanted by devoted followers. Not only does the Dhammapada represent the long and rich monastic tradition of memorizing the teachings of the Buddha, but it also expresses the most fundamental teachings of the Buddha which, from a practitioners standpoint, should always remain at the forefront of one's mind.

Mindfulness of Breath: The Fundamental Key

Three Steps to Awakening: A Practice for Bringing Mindfulness to Life

By Larry Rosenberg

By Laura Zimmerman

In their introduction to Three Steps to Awakening, authors Larry Rosenberg and Laura Zimmerman ask the question:

"Is it possible for a natural, fundamental process, such as breathing in and out, to provide the foundation for a liberating meditation practice?"

They then state that "The Buddha would answer yes. He realized that the process of respiration, so often taken for granted, comprises the basis for a method of awakening available to all of you."

Drawing on the above statement, the Rosenberg and Zimmerman investigate the Buddha's method of breath awareness as an approach to liberation and well-being, presenting a threefold approach—hence, the Three Steps to Awakening. Their approach includes:

- breath awareness

- breath as anchor

- choiceless awareness (ie., awareness itself without effort or an object of focus such as the breath)

Having the three methods in one’s repertoire gives one meditation resources for any life situation. In a time of stress, for example, one might use breath awareness exclusively. Or on an extended retreat, one might find choiceless awareness more appropriate. The three-step method has been taught to Larry’s students at the Cambridge Meditation Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for many years.

Applying The Four Foundations of Mindfulness

Touching the Infinite: A New Perspective on the Buddha’s Four Foundations of Mindfulness

By Rodney Smith

Of the most well known teachings of the Buddha, the Four Foundations of Mindfulness described in the Satipatthana Sutta, or The Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness, illustrates a fundamental approach to Buddhist thought and practice. In his introduction to Touching the Infinite, Rodney Smith writes:

The practice of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness is a systematic confrontation with our belief systems that methodically removes the conditioned layers of our consensus reality, finally laying bare the ultimate reality that is the ground of being. In four integrated and interconnected practices, the Buddha lays out the entire spiritual landscape and skillfully guides us across the terrain toward the final unconditioned truth.

This particular practice of mindfulness, while contemplative in nature, involves a much more active style of mindfulness compared to focusing on the breath or movements of the body. Nonetheless, although active in nature, Smith argues that the purpose behind such contemplations is not to adhere to some superficial objectives of reality, rather, the point is to go beyond the conditioned truths such as impermanence and death.

Many interpretations of the Fourth Foundation have focused on the contemplative truths mentioned as the ground for our mindfulness, but such an interpretation does not move us toward greater depth, nor does it allow integration with the other foundations. I sense this foundation is pointing directly to the formless, which can only be characterized by what is seen within it since awareness has no formed qualities that can be described. He is encouraging us to move through the portal of emptiness back to the unconditioned ground of being (Nirvana).

Mindfulness in the Zen Tradition

Undying Lamp of Zen: The Testament of Zen Master Torei

By Zen Master Torei Enji

Edited and Translated by Thomas Cleary

This is a complete explanation of Zen practice written by one of the most eminent masters of pre-modern Japan. The author, Torei Enji (1721–1792), was best known as one of two “genius assistants” to Hakuin Ekaku, who was himself a towering figure in Zen Buddhism who revitalized the Rinzai school.

The concept 'right mindfulness' forms an important touchpoint throughout the book and comes under close examination in the appendix 'On Practice.'

The work of right mindfulness is the unsurpassed practice. If you have the work of right mindfulness, you don’t get stuck on formal practices and are not concerned with dignified manners. In principle and in fact, sitting and walking, right and wrong, action and repose, truth and untruth, in the world and beyond the world, all that’s necessary is not losing right mindfulness.

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind has become one of the great modern spiritual classics, much beloved, much reread, and much recommended as the best first book to read on Zen.

Similar to Sarah Shaw's definition of mindfulness as a universal, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi explains that mindfulness is a kind of wisdom beyond a particular form of philosophy. From the Zen Buddhist perspective, this wisdom is coupled with the philosophy behind emptiness and the teachings of the Prajñāpāramita—an essential Mahāyāna sūtra. In Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind Suzuki Roshi writes:

Mindfulness is, at the same time, wisdom. By wisdom we do not mean some particular faculty or philosophy. It is the readiness of the mind that is wisdom. So wisdom could be various philosophies and teachings, and various kinds of research and studies. But we should not become attached to some particular wisdom, such as that which was taught by Buddha. Wisdom is not something to learn. Wisdom is something which will come out of your mindfulness. So the point is to be ready for observing things, and to be ready for thinking. This is called emptiness of your mind. Emptiness is nothing but the practice of zazen.

The Path of Aliveness: A Contemporary Zen Approach to Awakening Body and Mind

In The Path of Aliveness, Zen and Taoist Qigong teacher Christian Dillo offers a path of meaningful transformation tailored to our times.

In terms of Zen mindfulness, Dillo gives a detailed and lucid account in chapter 4, "Mindfulness and Bodyfulness" and chapter 5, "The Four Gates of Mindfulness." He writes:

Mindfulness can be defined as the intention to bring attention to sensation without cognitive overlay. For example, mindfulness of breathing—the widely recommended starting point for mindfulness meditation—is usually instructed as bringing attention to one’s inhale and exhale, and when attention gets caught up in thinking, to gently bring it back to breathing. This “bringing of attention” doesn’t happen on its own; it requires intention.

Moreover, in discussing mindfulness from a philosophical point of view in line with Suzuki Roshi's point on mindfulness and wisdom above, Dillo explains that focusing on the breath reveals the dual structure of the mind in that a thought coproduces the sense of a thinking self. According to Dillo:

Since mindfulness practice frees attention from cognition—whether I fully understand that or not—it challenges this continuity of self and begins to engender something new. Buddhism traditionally refers to this transformed sense of self as “no self” or “nonself,” terms that tend to create quite a bit of confusion in Western culture.

The Little Book of Healing Zen: Japanese Rituals for Beauty, Harmony, and Love

By Paula Arai

Like Marie Kondo's Shinto principles for decluttering, Paula Arai uses rituals influenced by Japanese Zen for personal and relation nourishment and spiritual healing.

As mentioned in the examples above, the concept of mindfulness, through broad in definition, entails more than just focusing on the breath, and while the practice of engaging in one's activity with intention is an important aspect of mindfulness, the implications run deep. In fact, healing may very well be the real aim of Buddhist practice as indicated in Pico Iyer's introduction to The Little Book of Healing Zen.

It’s often been noted that the Buddha was at heart a doctor of the mind, neither perfect nor immortal but committed at every moment to trying to heal our unease...

In that regard, author Paula Arai exemplifies this point.

Healing rituals are concrete acts of compassion that can guide us through our lives, helping to decrease our fear and anxiety and to increase our awareness and connectedness. Such rituals flourish in the messiness of life conditions. They are not about right or wrong, nor are they exclusive to any particular tradition. Rather, healing rituals are driven by thoughtful intent and engage our deepest love. When attuned to this love, you can create rituals that are healing. And in turn, when you do a healing ritual, you are in harmony with your highest self.

Mindfulness in the Tibetan Tradition

Mindfulness in Mahāyāna (The Great Vehicle)

Mindfulness in Action: Making Friends with Yourself through Meditation and Everyday Awareness

By Chogyam Trungpa

Edited by Carolyn Rose Gimian

As Carolyn Rose Gimian writes in the preface to Mindfulness in Action,

Mindfulness in Action: Making Friends with Yourself through Meditation and Everyday Awareness is, as the title suggests, a book about mindfulness and its application in the context of our whole life. The book focuses on the practice of meditation as a tool for developing mindfulness and explores how mindfulness and awareness influence our everyday life. It is a book for people who want to explore mindfulness through the practice of meditation and also apply meditative insight in their lives. It includes instructions for the practice of meditation, as well as an in-depth look into the principles of mindfulness.

This book is great for anyone interested in learning the basics of sitting meditation and, as Trungpa Rinpoche puts it, "making friends with ourselves."

We also have an online course, Mindfulness in Action, taught be Carolyn Rose Giman!

Mindfulness in Action:

Making Friends with Yourself through Meditation and Everyday Awareness

Taught by Carolyn Rose Gimian

Minding Closely: The Four Applications of Mindfulness

Minding Closely presents key methods to working with the mind from a traditional approach taught by the Buddha. The Four Applications of Mindfulness include mindfulness of the body, feelings, the mind, and phenomena. Wallace goes into great detail while remaining easy and accessible for all readers. Likewise, he grounds the more esoteric philosophical points into practical application through guided meditation practices.

Illustrating the aim of his book, Wallace writes:

The ability to sustain close mindfulness is a learned skill that offers profound benefits in all situations. This book explains the theory and applications of the practice the Buddha called the direct path to enlightenment. These simple but powerful techniques for cultivating mindfulness will allow anyone, regardless of tradition, beliefs, or lack thereof, to achieve genuine happiness and freedom from suffering. By closely minding the body and breath, we relax, grounding ourselves in physical presence. Coming face to face with our feelings, we stabilize our awareness against habitual reactions. Examining mental phenomena nakedly, we sharpen our perceptions without becoming attached. Ultimately, we see all phenomena just as they are, and we approach the ground of enlightenment.

Mindfulness in Vajrayāna (The Diamond Vehicle)

By Chogyam Trungpa

Edited by Judith L. Lief

The Tantric Path of Indestructible Wakefulness, the third volume of the Profound Treasury of the Ocean of Dharma, is a compilation of the view and practices of Vajrayāna.

Just as mindfulness and concentrated awareness is emphasized in the Theravada and Mahāyāna tradition, it's also emphasized in Varjayāna. In her Editor's Introduction Judith Lief explains that Trungpa Rinpoche stressed the "importance of ongoing cultivation of mindfulness and awareness as the essential underpinning of vajrayana practice and understanding."

Recounting her experience in seminary, Lief writes:

Throughout his teachings, he kept coming back to the need for grounding in shamatha (mindfulness) and vipashyana (awareness). By alternating weeks of intensive shamatha-vipashyana with weeks of study, Trungpa Rinpoche’s seminary training gave his students a feel for the dynamic way in which meditation could inform study, as well as how study could enrich meditation. The practice atmosphere created by the days of group meditation created the kind of container that made it possible for students to hear the dharma in a deeper, more personal and heartfelt way. The power of such an atmosphere made it possible for a meeting of minds to occur between the teacher and his students.

Mindfulness in Mahamudra and Dzogchen

As mentioned above, the practice of mindfulness is incorporated into all traditions of Buddhism. In the Vajrayāna tradition, the practice of calming the mind and listening closely to teachings as a means of receiving transmission is largely an expression of mindfulness application. In this regard mindfulness in both the Dzogchen and Mahamudra tradition is emphasized as a means to connect deeply and fully with the teacher and the teachings through the practice of devotion and receiving insight into the nature of mind whether through direct teachings as described in The Royal Seal of Mahamudra or The Great Secret of Mind, or reading the words of inspired masters in books such as Sunlight Speech That Dispels the Darkness of Doubt.

The Royal Seal of Mahamudra

By The Third Khamtrul Rinpoche, Ngawang Kunga Tenzin

Translated by Gerardo Abboud

Mahamudra, or The Great Seal, is a body of teachings from the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism that emphasizes Sahajayoga or "coemergence."

Beginning with the close relationship between phenomena and mind and the immense benefits of meditating on the nature of mind, the Third Khamtrul Rinpoche offers careful instructions on the four yogas of mahamudra together with advice on how to recognize genuine progress and how to remove obstacles that arise during meditation.

Specifically regarding mindfulness, readers of secular or Pali-canon based presentations of mindfulness will find a very unique approach, e.g.,

What is meant by saying that the heart of all teachings and the root of all paths is encompassed by the undistracted mindfulness of one’s mind? As explained before, since one’s mind is the very thing that creates samsara, nirvana, good, bad, positive, negative, happiness, sorrow, and all the rest, everything converges in this mind. Therefore, the ground doer of samsara and nirvana being one’s mind, the ground root of samsara and nirvana is this very mind. So we should know that the path of undistracted mindfulness of the mind is the root of all meditations and indeed the unavoidable way to reach the essential truth.

The Great Secret of Mind: Special Instructions on the Nonduality of Dzogchen

By Tulku Pema Rigtsal

Translated by Keith Dowman

Dzogchen (Great Perfection) goes to the heart of our experience by investigating the relationship between mind and world and uncovering the great secret of mind's luminous nature. Weaving in personal stories and everyday examples, Pema Rigtsal leads the reader to see that all phenomena are the spontaneous display of mind, a magical illusion, and yet there is something shining in the midst of experience that is naturally pure and spacious. Not recognizing this natural great perfection is the root cause of suffering and self-centered clinging. After introducing us to this liberating view, Pema Rigtsal explains how it is stabilized and sustained in effortless meditation: without modifying anything, whatever thoughts of happiness or sorrow arise simply dissolve by themselves into the spaciousness of pure presence.

Regarding mindfulness in the context of Dzogchen, Tulku Rinpoche presents it in a manner unique to this tradition, e.g.,

For Dzogchen meditation, we need constant mindfulness, and there are two kinds. The first is conditioned mindfulness, the second ultimate mindfulness. For beginners, conditioned mindfulness is remembering what the lama taught and then applying it; that is meditation with a cause, which entails effort. Once that outer or preliminary meditation has been accomplished, the main practice is to abide in pure presence, where effort is unnecessary and meditation is natural and automatic. This is called “mindfulness of reality” and since it is effortless, we do not need to strive in any way to arrive there.

Translated by Thinley Norbu

With the wish to inspire and motivate practitioners, Kyabje Thinley Norbu Rinpoche has translated a selection of wisdom teachings into direct and simple English that retains the power of the original writings and their emphasis on practice. The authors are five of the most sublime scholar-saints of the Nyingma lineage of Tibetan Buddhism: Kunkhyen Longchenpa, Kunkhyen Jigme Lingpa, Patrul Rinpoche, Mipham Rinpoche, and Kyabje Dudjom Rinpoche.

Mindfulness, generally in the context of Dzogchen, appears throughout, in particular the translation of Jigme Lingpa's "Mindfulness, an Ocean of Qualities" which includes a variety of facets of mindfulness, e.g.,

Because I kept mindfulness too tightly, obstacles of vital air energy also occurred. In order to develop my practice, I communicated with and sought the advice of many noble Lamas, meditators, and fellow Dharma friends, yet no one except you has shown me the natural understanding of instantaneous mindfulness, which is the essence of meditation.

Some More Books Related to Buddhist Mindfulness

The Works of B. Alan Wallace: A Guide for Readers

The Works of B. Alan Wallace: A Guide for Readers

B. Alan Wallace has authored, translated, edited, and contributed to more than forty books on Tibetan Buddhism, science, and culture. With fourteen years as a Buddhist monk, he earned a BA in physics and the philosophy of science and then a PhD in religious studies. After teaching in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he founded the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies to explore the integration of scientific approaches and contemplative methods.

We have a wide selection of books written and translated by Alan Wallace. Discover more below!

B. Alan Wallace on Buddhist Meditation Practice

Lojong "Mind Training"

The Art of Transforming the Mind: A Meditator’s Guide to the Tibetan Practice of Lojong

The purpose of lojong, a traditional Mahayana Buddhist practice of training the mind, is about transforming one’s attitude and expanding one’s sense of self to encompass the greater whole. In this modern presentation of lojong practice and Atisha’s Seven-Point Mind Training, author, translator, and Buddhist practitioner B. Alan Wallace gives readers a framework from which they may cultivate the qualities of loving-kindness, compassion, and insight while diminishing harmful habits and ways of thinking. “All of us have attitudes,” Wallace explains, and “attitudes need adjusting.” The practice of lojong is therefore presented as a method to shift our attitude away from our problems, anxieties, hopes, and fears toward an expansive sense of joy and well-being that springs from the very essence of Mahayana—bodhichitta.

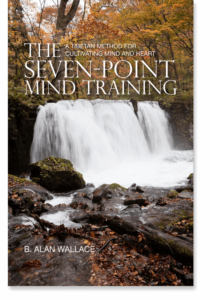

The Seven-Point Mind Training: A Tibetan Method for Cultivating Mind and Heart

By B. Alan Wallace

Edited by Zara Houshmand

In this society, with its hurly-burly pace demanding of our time, it is ever so easy to let life slip by. Looking back after ten, twenty, thirty, years—we wonder what we have really accomplished. The process of simply existing is not necessarily meaningful. And yet there is an unlimited potential for meaning and value in this human existence. The Seven-Point Mind Training is one eminently practical way of tapping into that meaning. At the heart of the Seven-Point Mind Training lies the transformation of the circumstances that life brings us, however hard as the raw material from which we create our own spiritual path. The central theme of the Seven-Point Mind Training is to make the liberating passage from the constricting solitude of self-centeredness to the warm kinship with others which occurs with the cultivation of cherishing others. This Mind Training is especially well-suited for an active life. It helps us to reexamine our relationships—to family, friends, enemies, and strangers—and gradually transform our responses to whatever life throws our way.

Four Immeasurables

The Four Immeasurables: Practices to Open the Heart

By B. Alan Wallace

Edited by Zara Houshmand

The Four Immeasurables—the cultivation of loving-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity—is a rich suite of practices that open the heart, counter the distortions in our relationships to ourselves, and deepen our relationships to others. Alan Wallace presents a unique interweaving of teachings on the Four Immeasurables with instruction on meditative quiescence, or shamatha practice, to empower the mind. This book includes both guided meditations and lively discussions on the implications of these teachings for our life.

Also available as an audiobook. See below.

Other Styles of Meditation

Minding Closely: The Four Applications of Mindfulness

Bringing in his experience as a Buddhist monk, scientist, and contemplative, Alan Wallace offers a rich synthesis of Eastern and Western mindfulness traditions, along with a comprehensive range of guided meditation practices interwoven throughout the text. The meditations are systematically presented, beginning with very basic instructions, which are then gradually built upon as one gains increasing familiarity with the practice.

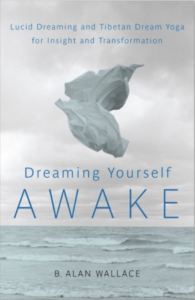

Dreaming Yourself Awake: Lucid Dreaming and Tibetan Dream Yoga for Insight and Transformation

By B. Alan Wallace

Edited by Brian Hodel

Some of the greatest of life’s adventures can happen while you’re sound asleep. That’s the promise of lucid dreaming, which is the ability to alter your own dream reality any way you like simply by being aware of the fact that you’re dreaming while you’re in the midst of a dream. There is a range of techniques anyone can learn to become a lucid dreamer—and this book provides all the instruction you need to get started. But B. Alan Wallace also shows how to take the experience of lucid dreaming beyond entertainment to use it to heighten creativity, to solve problems, and to increase self-knowledge. He then goes a step further: moving on to the methods of Tibetan Buddhist dream yoga for using your lucid dreams to attain the profoundest kind of insight.

Translations by B. Alan Wallace

Balancing the Mind: A Tibetan Buddhist Approach to Refining Attention

For centuries, Tibetan Buddhist contemplatives have directly explored consciousness through carefully honed and rigorous techniques of meditation. B. Alan Wallace explains the methods and experiences of Tibetan practitioners and compares these with investigations of consciousness by Western scientists and philosophers. Balancing the Mind includes a translation of the classic discussion of methods for developing exceptionally high degrees of attentional stability and clarity by fifteenth-century Tibetan contemplative Tsongkhapa.

How to Practice Shamatha Meditation: The Cultivation of Meditative Quiescence

By Gen Lamrimpa

Edited by Hart Sprager

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

In 1988, Gen Lamrimpa, a Tibetan monk, led a one-year retreat in the Pacific Northwest, during which a group of Western meditators devoted themselves to the practice of meditative quiescence (shamatha). This book is a record of the oral teachings he gave to this group at the outset of the retreat. The teachings are brought to life by Gen Lamrimpa's warmth, humor, and extensive personal experience as a contemplative recluse. An invaluable practical guide for those seeking to develop greater attentional stability and clarity, this work will be of considerable interest to meditators, psychologists, and all others who are concerned with the potentials of the human mind.

By Gen Lamrimpa

Edited by Ellen Posman

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

Realizing emptiness or grasping the true nature of reality lies at the heart of the Buddhist path. In this book, Gen Lamrimpa offers practical instruction on Madhyamaka, insight meditation aimed at realizing emptiness. Drawing on his theoretical training as well as his extensive meditative experience, he explains how to use Madhyamaka reasoning to experience the way in which all things exist as dependently related events.

A Spacious Path to Freedom: Practical Instructions on the Union of Mahamudra and Atiyoga

By Karma Chagme

Commentaries by Gyatrul Rinpoche

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

This manual of Tibetan meditation simply and thoroughly presents the profound Dzogchen and Mahamudra systems of practice. Karma Chagmé sets forth the stages of meditation practice, including the cultivation of meditative quiescence and insight, the experiential identification of awareness, and the highest steps of Mahamudra and Atiyoga, leading to perfect enlightenment in one lifetime. Drawing from his enormous textual erudition and mastery of Tibetan oral traditions, he shows how these two meditative systems can be unified into a single integrated approach to realizing the ultimate nature of consciousness.

Meditation, Transformation, and Dream Yoga

By Gyatrul Rinpoche

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

Translated by Sangye Khandro

The three traditional Nyingma texts and Venerable Gyatrul Rinpoche's commentary included in this book were selected by him for their relevance to the modern-day spiritual aspirant who must combine and balance quality practice time, work time, and rest time in the course of a busy day. Guidelines for formal sitting are presented here from the Dzogchen perspective in the teachings on quiescence meditation. Practices for bringing the experiences of daily life into the spiritual path are presented in the section on transformation. Finally, the teachings on dream yoga guide the practitioner in the conscious control of the dream state as well as the bardo state at the end of life. Ven. Gyatrul Rinpoche's dynamic and practical commentaries on each section are specially tailored to the needs of Western students. The result is an indispensable handbook for practitioners at all levels of experience. When the Venerable Gyatrul Rinpoche arrived in the West many decades ago, he was already a receptacle for an abundance of transmissions received from many of the foremost and authentic masters of our times. Since then, his noble disposition and advanced level of meditation practice has assisted innumerable people, and he has established many Dharma centers.

Healing from the Source: The Science and Lore of Tibetan Medicine

By Yeshi Dhonden

Edited by B. Alan Wallace

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

In this remarkable contemporary presentation of the theory and practice of Tibetan medicine, Dr. Yeshi Dhonden, twenty years the personal physician of H.H. the Dalai Lama, draws from over fifty years of practicing and teaching this ancient tradition of healing. This volume vividly presents a series of lectures Dr. Dhonden gave before a group of health care professionals at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. This lecture series was presented during the planning stages of a research project at the University of California San Francisco to test Dr. Dhonden's medical treatment for metastatic breast cancer. (This research project caught the interest of NBC's Dateline, which filmed an hour-long documentary of it that aired in January 2000.) Dr. Dhonden elucidates the holistic Tibetan medical view of health and disease, referring to traditional Tibetan medical sources as well as his own experiences as a doctor practicing in Tibet India and numerous countries throughout Europe and America. His presentation is delightfully complemented by many anecdotes drawing from the ancient lore of popular folk medicine in Tibet. For health care professionals, anthropologists, historians of medicine, medical ethicists, and the general public interested in Tibetan medicine, this book is a fascinating contribution by one of the foremost practitioners of Tibetan medicine in the modern world.

Naked Awareness: Practical Instructions on the Union of Mahamudra and Dzogchen

By Karma Chagme

Commentaries by Gyatrul Rinpoche

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

Edited by B. Alan Wallace

Edited by Lindy Steele

In this classic seventeenth-century presentation of the union of Mahamudra and Dzogchen, Karma Chagmé, one of the great teachers of both these lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, begins with an overview of the spirit of awakening and the nature of actions and their ethical consequences. Next, drawing from his enormous erudition and profound experience, Chagmé gives exceptionally lucid instructions on the two phases of Dzogchen practice—the "breakthrough" and the "leap-over"—followed by an accessible introduction to the practice of the transference of consciousness at the time of death. The concluding chapters of this treatise present a detailed analysis of Mahamudra meditation in relation to Dzogchen practice. This tour de force of scholarly erudition and contemplative insight is made all the more accessible by the lively commentary of the contemporary Nyingma Lama Gyatrul Rinpoche.

Calming the Mind: Tibetan Buddhist Teachings on Cultivating Meditative Quiescence

By Gen Lamrimpa

Edited by Hart Sprager

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

To stabilize the mind in one-pointed concentration is the basis of all forms of meditation. Gen Lamrimpa was a meditation master who lived in a meditation hut in Dharamsala and who had been called to teach by the Dalai Lama. He leads the meditator step-by-step through the stages of meditation and past the many obstacles that arise along the way. He discusses the qualities of mind that represent each of nine levels of attainment and the six mental powers.

A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life

By Shantideva

Translated by Vesna A. Wallace

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

In the whole of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, there is no single treatise more deeply revered or widely practiced than A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life. Composed in the eighth century by the Indian Bodhisattva Santideva, it became an instant classic in the curricula of the Buddhist monastic universities of India, and its renown has grown ever since. Santideva presents methods to harmonize one's life with the Bodhisattva ideal and inspires the reader to cultivate the perfections of the Bodhisattva: generosity, ethics, patience, zeal, meditative concentration, and wisdom.

Buddhism and Science

Embracing Mind: The Common Ground of Science and Spirituality

By Brian Hodel

By B. Alan Wallace

What is Mind? For this ancient question we are still seeking answers. B. Alan Wallace and Brian Hodel propose a science of the mind based on the contemplative wisdom of Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Christianity, and Islam.

The authors begin by exploring the history of science, showing how science tends to ignore the mind, even while it is understood to be the very instrument through which we comprehend the world of nature. They then propose a contemplative science of mind based on the sophisticated techniques of meditation that have been practiced for thousands of years in the great spiritual traditions. The final section presents meditations that are of universal relevance—to scientists and people of all faiths—for revealing new dimensions of consciousness and human flourishing.

Embracing Mind moves us beyond the dogmatic debates between theists and atheists over Intelligent Design and Neo-Darwinism, and it returns us to the vital core of science and spirituality: deepening our experience of reality as a whole.

Choosing Reality: A Buddhist View of Physics and the Mind

Choosing Reality shows how Buddhist contemplative methods of investigating reality are relevant for modern physics and psychology. How shall we understand the relationship between the way we experience reality and the way science describes it? In examining this question, Alan Wallace discusses two opposing views: the realist view, which argues that scientific theories represent objective reality, and the instrumentalist view, which states that concepts cannot describe what exists independently of them. Finding both of these philosophies of science inadequate, the author explores the Buddhist middle way view and the relevance for modern physics of Buddhist contemplative methods of investigating reality. He also examines the ideas of body, mind, and reincarnation from the viewpoint of Tibetan Buddhism.

A Reader's Guide to Shantideva and the Way of the Bodhisattva

and The Way of the Bodhisattva

A Reader's Guide to the Way of the Bodhisattva

The great nineteenth-century master Patrul Rinpoche, author of The Words of My Perfect Teacher and revered by all Tibetan Buddhists, was known for his wandering ascetic lifestyle, eschewing fame, generous offerings, and all but the most meager possessions. However, wherever he went throughout his peripatetic life, he carried with him a copy of Shantideva's Bodhicharyavatara, which we know now as The Way of the Bodhisattva or A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life. Renowned for his encyclopedic knowledge and ability to transmit the wisdom of Prajnaparamita and Dzogchen, Patrul Rinpoche spent his life constantly teaching this text, encouraging students to read it and study it over and over again-hundreds of times. Why this focus from him and millions of masters and practitioners before and after?

Below is a guide to help practitioners answer this question for themselves and go deeper and deeper into this essential work. For a bit of history, you can also see our post on its story.

Jump To: Translations | Commentaries | Chapter-Specific Works | Additional Works | Resources

Translations of the Bodhicharyavatara

Entering the Way of the Bodhisattva: A New Translation and Contemporary Guide

This modern translation of an essential Mahayana Buddhist text captures the meaning and musicality of Shantideva's original verse and a commentary to its profound depths by the translator David Karma Choephel , one of the very few western Khenpos.

This is a fresh translation to, and commentary on the Bodhicaryavatara or Entering the Way of the Bodhisattva, perhaps the most renowned and thorough articulation of the bodhisattva path. Written by the eighth-century Indian monk Shantideva, Entering the Way of the Bodhisattva is a guide to becoming a bodhisattva, someone who is dedicated to achieving enlightenment in order to benefit all beings.

After the full translation, Khenpo David Karma Choephel gives his own commentary, explaining the key points of each chapter with clarity and wisdom. Combining a uniquely poetic translation with detailed analysis, this book is a comprehensive guide to developing oneself in service of others. Teachings that have been at the heart of Mahayana practice for centuries are given new life, and the supporting commentary makes the text accessible and applicable to practitioners. Readers interested in the bodhisattva path will find this a comprehensive resource filled with captivating verse and incisive interpretations.

Paperback | eBook

$21.95 - Paperback

Shambhala Library Hardcover | Paperback | eBook | MP3 audio download.

$24.95 - Hardcover

The Way of the Bodhisattva

By far the best-selling translation is from the Padmakara Translation Group entitled The Way of the Bodhisattva. This was translated with reference primarily to the Tibetan and following the commentary of Khenpo Kunpel, the nineteenth-century Nyingma master renowned for his spiritual realization and instrumental in the preservation of the oral traditions and teachings of his tradition.

This edition also includes a ten-page biography of Shantideva as well as selections on tonglen, or exchanging oneself with others, from Khenpo Kunpel's commentary.

A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life:

Another excellent translation is from Alan and Vesna Wallace, translated as A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life. The Wallace's translation is based both on Sanskrit and Tibetan sources and was guided by Tibetan commentaries, notably of Gyaltsap-Je.

Another version to note is Kate Crosby and Andrew Skilton's translation from Oxford University Press. All these translations expose different facets of the text, while the translators' introductions each illuminate it in different ways and are well-worth seeking out.

Paperback | eBook

$16.95 - Paperback

Commentaries

Paperback | eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Nectar of Manjusri's Speech: A Detailed Commentary on Shantideva's Way of the Bodhisattva

by Khenpo Kunzang Pelden, based on Patrul Rinpoche's teachings

While Patrul Rinpoche did not compose a work on the Way of the Bodhisattva, he taught it constantly, over one hundred times from beginning to end. It had fallen into disuse outside a few monastic centers, and it is thanks to Patrul Rinpoche this text became integral to all the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Luckily for us, one of his most dedicated students, Khenpo Kunzang Pelden or Khenpo Kunpel, compiled these teachings he received from Patrul Rinpoche and composed The Nectar of Manjusri's Speech: A Detailed Commentary on Shantideva's Way of the Bodhisattva.

Paperback | eBook | Pocket Edition | mp3 Audio

$21.95 - Paperback

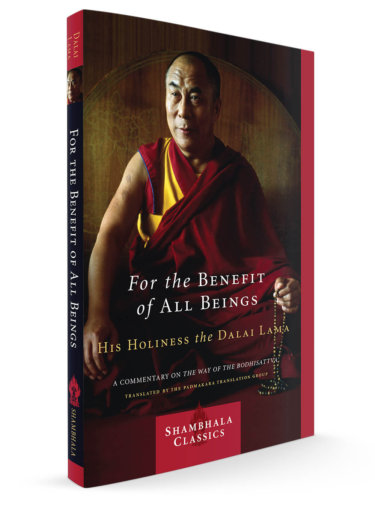

For the Benefit of All Beings: A Commentary on The Way of the Bodhisattva

by the Dalai Lama and the Padmakara Translation Group

Based on teachings His Holiness gave in Dordogne, France in 1991, For the Benefit of All Beings, translated by the Padmakara Translation Group, gives an overview and commentary on each chapter of the text, distilling the key messages on the benefits of bodhichitta, offering and purification, carefulness, attentiveness, patience, endeavor, concentration, wisdom, and dedication. His Holiness said,

"I received the transmission of the Bodhicharyavatara from Tenzin Gyaltsen, the Kunu Rinpoche, who received it himself from a disciple of Dza Patrul Rinpoche, now regarded as one of the principal spiritual heirs of this teaching. It is said that when Patrul Rinpoche explained this text, auspicious signs would occur, such as the blossoming of yellow flowers, remarkable for the great number of their petals. I feel very fortunate that I am in turn able to give a commentary on this great classic of Buddhist literature."

Paperback | eBook | CD | Digital Download

$29.95 - Paperback

Becoming Bodhisattvas: A Guidebook for Compassionate Action

by Pema Chōdrōn

In Becoming Bodhisattvas: A Guide to Compassionate Action (previously published as No Time to Lose: A Timely Guide to the Way of the Bodhisattva), Ani Pema Chödrön talks about her relationship with the text and said it was not always easy:

"Some people fall in love with The Way of the Bodhisattva the first time they read it, but I wasn't one of them. Truthfully, without my admiration for Patrul Rinpoche, I wouldn't have pursued it. Yet once I actually started grappling with its content, the text shook me out of a deep-seated complacency, and I came to appreciate the urgency and relevance of these teachings. With Shantideva's guidance, I realized that ordinary people like us can make a difference in a world desperately in need of help."

Giving Our Best: A Retreat with Pema Chodron on Practicing the Way of the Bodhisattva

by Pema Chödrön

Pema Chödrön's teachings on this text are also available in the form of Giving Our Best: A Retreat with Pema Chödrön on Practicing the Way of the Bodhisattva. This is a rare and wonderful presentation from a live teaching that brings the teachings into real life, present-day situations.

Chapter-Specific Commentaries

We have two books on the Patience or fourth chapter and three on the Wisdom, or ninth chapter.

Paperback | eBook | Audiobook

$16.95 - Paperback

Peaceful Heart: The Buddhist Practice of Patience

An introductory guide to cultivating patience based on The Way of the Bodhisattva's Fourth Chapter on patience, and opening your heart to difficult circumstances from leading Buddhist teacher, Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche.

Also available as an audiobook

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche talks about his book at the Jaipur Literature Festival

Paperback | eBook

$18.95 - Paperback

Perfecting Patience: Buddhist Techniques to Overcome Anger

His Holiness the Dalai Lama also has a book devoted to Shantideva's chapter on patience. Here His Holiness relates that:

"Shantideva observes that from one point of view, as pointed out earlier, when the other person inflicts harm or injury upon one, that person is accumulating negative karma. However, if one examines this carefully, one will see that because of that very act, one is given the opportunity to practice patience and tolerance. So from our point of view it is an opportune moment, and we should therefore feel grateful toward the person who is giving us this opportunity. Seen in this way, what has happened is that this event has given another an opportunity to accumulate negative karma, but has also given us an opportunity to create positive karma by practicing patience. So why should we respond to this in a totally perverted way, by being angry when someone inflicts harm on us, instead of feeling grateful for the opportunity?"

Paperback | eBook

$16.95 - Paperback

Perfecting Wisdom: How Things Appear and How They Truly Are

by The Dalai Lama

The ninth chapter of the Bodhicaryavatara, on wisdom, is considered one of the most profound and requires deep study and practice to truly understand. In this work, His Holiness the Dalai Lama focuses on this chapter and its application. Here, His Holiness goes deep into the subjects of the methods needed to cultivate wisdom, what identitylessness means, and how the notion of true existence is refuted.

The Wisdom Chapter

by Mipham Rinpoche, based on teachings he received from Patrul Rinpoche

Patrul Rinpoche, also imparted teachings to Mipham Rinpoche, who based his understanding on these when he wrote his commentary on the famous (and famously challenging) ninth chapter of The Way of the Bodhisattva, now translated as The Wisdom Chapter.

Hardcover | eBook

$78.00 - Hardcover

The Center of the Sunlit Sky: Madhyamaka in the Kagyu Tradition

by Karl Brunnholzl

Another in-depth look at this text - in particular the ninth chapter - is Pawo Rinpoche's explanation included in The Center of the Sunlit Sky. In just under 200 pages of this work, in addition to being a commentary on Shantideva's work generally, Pawo Rinpoche provides several long accounts on such topics as Madhyamaka in general, the distinction between different branches of Madhyamaka philosophy, prajña, emptiness, conventional and ultimate reality, and the nature and qualities of Buddhahood. It describes the four major Buddhist philosophical systems and how the Mahayana represents the words of the Buddha. In addressing the issue of so-called Shentong-Madhyamaka, he also elaborates on the lineage of vast activity and shows that it is not the same as mind only.

This is available in both hardcover and eBook (see Additional Formats).

Additional Works on The Way of the Bodhisattva

Paperback | eBook

$27.95 - Paperback

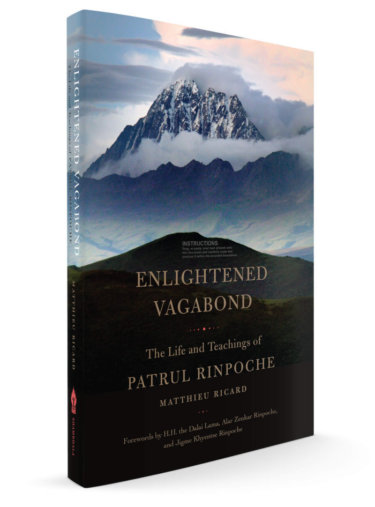

Enlightened Vagabond: The Life and Teachings of Patrul Rinpoche

by Matthieu Ricard

2017 also saw the release of Enlightened Vagabond, the collected stories about Patrul Rinpoche who led a revival of the focus and immersion of students on this text. The stories often revolve around him teaching on this text which he did countless times. Here is an example:

Patrul and the Prescient Monk

—from Enlightened Vagabond

Patrul was famous for his teachings on The Way of the Bodhisattva. He might take days, weeks, or months to comment on the entire text, teaching at whichever level of complexity was most suitable to the occasion, from brief and quintessential to extensive and complex. Often, he’d advise students to read the text before he gave his commentary. After he was done, he’d tell students to read it another hundred times.

"Patrul himself had received teachings on The Way of the Bodhisattva more than a hundred times. He taught the text more than a hundred times, yet even so, he used to say that he had not grasped its full meaning. One night, a monk at Trago Monastery dreamed that he saw a lama who he felt was Shantideva in person, the author of The Way of the Bodhisattva. The next morning, when a wandering lama arrived at Trago Monastery, the monk recognized him: He looked just like the figure who had appeared in his dream the night before! The monk approached the lama—who in fact was Patrul Rinpoche. Bowing respectfully, he requested that he teach The Way of the Bodhisattva. Bowing back, the lama agreed. Patrul gave the teachings. When he left, the monk who had seen him in his dream went with him, accompanying him along the way for several days’ walk."

Paperback | eBook

$22.95 - Paperback

Destroying Mara Forever: Buddhist Ethics Essays in Honor of Damien Keown

Another work that should be mentioned is Destroying Mara Forever, a collection of essays on Buddhist ethics including three pieces focused on this text.

The first is by Barbara Clayton entitled Santideva, Virtue, and Consequentialism.

The second, by Paul Williams, is entitled Is Buddhist Ethics Virtue Ethics? The final piece that is Shantideva-specific is Daniel Cozort's Suffering Made Sufferable: Santideva, Dzongkaba, and Modern Therapeutic Approaches to Suffering's Silver Lining. These three pieces explore different ethical implications and significance of Shantideva's work

Additional Resources

Please visit The Way of the Bodhisattva: An Immersive Workshop for more on Shantideva's work, or sign up for our Tibetan Buddhist email list for more information.

The Way of the Bodhisattva Resources

This recent piece from CBS considers that lucid dreaming might actually be possible. But for those for whom understanding the mind on an experiential level is a way of life, lucid dreaming is not only possible, but can serve as a genuine practice on the path of realization.

Our book by B. Alan Wallace, Dreaming Yourself Awake, is an instruction manual for lucid dreaming and Tibetan dream yoga. Wallace lays out techniques that trigger awareness in the dream state to heighten creativity, to solve problems, and to increase self-knowledge. We also publish a few additional books on dream yoga.

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

The Dalai Lama on Questions Concerning the Lack of Intrinsic Existence

The following article is an excerpt adapted from

HH the Dalai Lama understands that questions (or “qualms”) naturally arise for students as they think about key Buddhist tenets. In this adaptation from his book Transcendent Wisdom (now published as Perfecting Wisdom)—translated and edited by B. Alan Wallace—he brings up qualms and gives his responses about what it means for things to be real or not real.

Qualm: If it is an error to think of form and so forth as real, how can it be that we verifiably perceive them? What further criterion beyond verifying perception is needed to establish the true existence of entities?

Response: Such entities are indeed verifiably perceived. However, when we say “verifying cognition” this suggests infallibility. It is a non-deceptive awareness with reference to the appearance of a self-defining object. Realists—those who assert true existence—have just this in mind when speaking of verifying cognition. They believe that phenomena appear just as they exist, and they appear to be truly existent. They call a cognition that is non-deceptive with regard to that appearance “verifying.”

Now in the Centrist context, infallible cognition is acknowledged, while denying that there is any such thing as even conventional intrinsic existence. Such cognition is said to be deceptive with regard to the appearance of phenomena as intrinsically existent. The Prasangikas, who hold this view, do not accept verifying cognition with respect to such appearance. Thus, they allow that a deceptive awareness may nevertheless verify its object. Therefore, phenomena exist by the power of consensus, not by their own intrinsic reality.

Such phenomena as form are regarded as misleading, for their mode of appearance and their mode of existence are not in accord with each other. Common people regard impure objects as pure, for the way those objects appear belies the way they actually exist. Although they are thought by consensus to be pure, that conviction is false. Likewise, although phenomena are not truly existent, they appear as if they were; and thus they are asserted to be misleading.

Qualm: The Lord Buddha is recorded in the scriptures as saying that all composites are impermanent and all tainted things are unsatisfactory. Thus, when the Buddha taught the Four Noble Truths, he spoke of sixteen attributes, including impermanence. Are those not ultimate truths; are they not absolute?

Response: The Buddha taught these in order for people to enter into the experience of emptiness; but ultimately speaking, there is no such thing as the impermanence of a pot. Ultimately, events are not momentary. Ultimately, the object itself does not exist, so it has no properties such as impermanence.

Qualm: If one takes the position that ultimately events are not of a momentary nature, does that mean that the conventional presentation of phenomena as passing away moment by moment is incorrect?

Response: No, that is not incorrect. That momentary nature is established by conventionally verifying cognition, so we accept that on a conventional basis. All the sixteen attributes of the Four Noble Truths are conventionally realized by contemplatives, so we can accept them.

Qualm: Well then, can we not call those sixteen “reality”?

Response: Common people mistake things that are essentially impermanent as permanent, and impure things as pure. In comparison to such attitudes, the contemplative experiences reality. It is conventional reality.

Qualm: If you deny true existence, do you still assert that one accumulates merit by making offerings to Awakened Beings and so on?

Response: Yes. One engages in illusion-like actions, and illusion-like fruits of those actions ensue. For example, Realists, who assert true existence, maintain that from real actions, real merit is accumulated and real results are experienced. The Centrists acknowledge the accumulation of merit and the effects of actions but as not truly existent.

Qualm: If sentient beings are like illusions, how can they take birth again after having died?

Response: An illusion is not truly existent. If an illusion appears as a horse or elephant, it does not exist as such. Although it is not real, it appears due to a complex of conditions, and it vanishes due to the cessation of that complex of conditions. So even an illusion depends upon causes and conditions. One cannot establish duration as a criterion for true existence.

Books by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

Heartache, Headache, and Meditation: What Are the Signs of a Practice Going Wrong?

The following article is adapted from The Four Immeasurables: Practices to Open the Heart by B. Alan Wallace.

Dealing with Problems in Shamata Practice

If your practice is wholesome and enjoyable, maintained with a sense of buoyancy and well-being, the chances are extremely remote that any problems that are catalyzed in meditation will become entrenched. Almost every case I have encountered of persistent problems in samatha practice is characterized by a lack of buoyancy and a reliance on sheer discipline. Typically, when samatha practice goes wrong, it gets heavy—frustrating and isolated, barren and dark. You may feel you have to muscle your way through, and of course that makes it worse.

Physical tension, aches and pains, are not necessarily indications of a problem. In the early stages especially, tension in the body may be brought on more by the mind than by muscle fatigue, or some other purely physical factor. People’s knees may hurt when they are meditating and feel fine at any other time, even if they are sitting motionlessly for long periods of time. Part of the mind wants an excuse. If the pain is caused by this sort of influence from the mind, then make a choice. Recognize that the tension is not really debilitating, and just let it go.

If the problem tends to linger between sessions, and especially if it’s conjoined with an array of other symptoms that suggest an imbalance in your nervous system, you should be more careful. Such symptoms include tension, a feeling of darkness or heaviness at the heart that lingers, a gloom in the mind that may slip into depression or irritability, nervousness, and a tendency to weep—not a refreshing, cleansing weeping, but just grief. If you recognize one or more of those occurring in a chronic fashion, then something has gone wrong. It’s time to lighten up, speak with the teacher, and clear it out. If you are on your own, the first thing to do is lighten up the intensity of the practice. Ease off and let yourself be a little bit lazy. You might try some yoga: that’s what it’s for. Above all, bring in a greater sense of buoyancy and find something to restore good cheer and lightness to the mind. If you can do that, in all likelihood, you will knock out the problem. When the mind’s joy, its buoyancy and lightness, becomes a distant memory, that’s when these symptoms can really set in persistently and become problematic.

If you ever experience a dense, dark, tight, fisty quality, especially in the area of your heart or the center of your chest, back off immediately. Back off just as if you found a snake in your lap. It’s really important not to pursue the meditation if this happens, as great damage can be done. Do something cheerful instead. Go eat pizza and ice cream; listen to your favorite music. Do whatever you can to bring lightness back in and get out of that space quickly.

Why would this happen? The heart center is closely connected to mental consciousness. There is a vital energy in the body that you can experience in a tactile way, even though it is not physical in the Western scientific sense. (There is no place for “vital energy” in modern physics. I don’t think there ever will be; it’s a different type of phenomenon. This is a type of “qualia” that is experienced first-hand, not something existing purely objectively, independently of experience.) But it manifests, among other ways, as the physical sensations at your heart that accompany different emotional states. When you feel buoyant and happy, when you feel excited, when you feel heavy and depressed, when you feel like dirt: check the physical sensations at your heart. For any of the major mind states, you can probably feel the corresponding vital energy if you attend to it.

In samatha practice, you are doing something very unusual with and to your mind. You’re asking it to focus on one thing and stay there. That means you are, in a sense, compacting your attention. You’re channeling and collecting it, gathering it together. As you gather your mind, you also gather your vital energies, drawing them to the heart. If the quality of awareness that you are compacting has negative elements such as resentment, guilt, depression, sadness, or fear, that will also show up in the heart as a sensation of heavy darkness, a feeling like you have just swallowed a rock.

The Tibetans describe this as “bad energy” (rlung ngan pa), and of course that is just what it feels like. It is dangerous, because the energy can get lodged in the heart and stay there. That may lead to chronic depression, or worse. It’s unfortunate, and it happens unnecessarily to too many meditators. You can work through it but it’s difficult, and it’s far better not to fall into it in the first place. If it does start, the sooner you deal with it, the easier it will be. How do you address it? You need to bring a lot of buoyancy and light into your life and you probably shouldn’t meditate much. If you do meditate, the sessions should be very short and very light; lovingkindness practice is appropriate, but never to the point where it gets oppressive or heavy in any sense. You need to keep a lightness in your life, do things that you enjoy, spend time with people you enjoy. If you have a spiritual teacher, think about him or her a lot. Do whatever you can to introduce a quality of lightness, sweetness, and warmth into your heart and mind. You really have to take major steps to counter the dark, cold, heaviness of this problem, and be very patient about returning to any kind of intensive meditation. You have to take a leave of absence for a while.

It is unusual, but similar problems to those associated with the heart center can sometimes happen when breath awareness with a focus on the nostrils concentrates too much energy in the head. You may find your head feeling full and bloated like a pumpkin on top of your neck. Or you may experience a feeling of pressure in the head, or headaches. If this happens, drop that technique for a while. Bring the awareness down to the abdomen or diffuse it gently throughout the whole body, but get it out of the head. It’s not healthy; if you continued slogging on with that technique, it could become a chronic problem and there is really no reason to let that happen. Headaches should not become common as a result of practice. If they occur once in a while, that’s normal. But if you find you’re getting headaches from meditation with any degree of regularity at all, then something is wrong and needs to be checked. If headaches become at all consistent, please speak with a qualified teacher.

On the other hand, you may experience many unusual physical sensations in samatha practice that are not at all cause for concern. People commonly report bizarre experiences such as distortions of the sense of physical space, illusions of movement or falling, a sense that the limbs are contorted, or a ringing in the ears. You may feel as if your body is swelling up like the Pillsbury doughboy, or it may feel rooted to the earth. In general, when such experiences involve the whole body, or are peripheral, focused on the limbs, they are not danger signs at all, but quite harmless. The traditional instructions are to ignore such phenomena, hard as that may be. By paying attention to a sensation or becoming fixated on it, you perpetuate it and it can then turn into an obstacle.

The reason behind such experiences is that samatha has a profound effect on the vital energy system in the body. We are doing something the mind is not at all accustomed to, plunking the mind down and saying: Stay! As you concentrate and channel the mind in an unfamiliar way, especially if you go to greater depths than you have previously, this is bound to have an effect on the vital energies. They start to rearrange themselves. This continues all through the course of developing samatha, all the way to its culmination. When you actually attain samatha, there is a radical shift of vital energies. It’s like having your whole house rewired: the energies will function differently, and your body will feel extraordinarily light and pliant. From then on, unless you let your samatha deteriorate, that becomes your normal physical state. Prior to the actual achievement of samatha there’s a lot of rearranging of the furniture, so to speak, as the energies shift around. And as this takes place, you may feel strange physical sensations, perhaps even as if your body is rotating or turning upside down.

What if you are not sure if something you are experiencing might be problematic? There are two types of teachers: one is your own intuition, the other is an outside source. If you have a very strong sense something is worth exploring, do so. Release yourself into it and experiment. If you have problems, come back and check with an outside source. If you have a recurring problem with headaches or a heaviness of the heart, I suggest you consult a qualified meditation teacher. If you ever start developing a chronic sense of fatigue and tension in the meditation, or a chronic sense of darkness around the mind, that’s a time to stop and take appropriate countermeasures. Come and talk to a teacher. Get it early and nip it in the bud. Don’t let it linger and become an embedded problem.

Other Books Related to the Four Immeasurables

B. Alan Wallace has authored, translated, edited, and contributed to more than forty books on Tibetan Buddhism, science, and culture. With fourteen years as a Buddhist monk, he earned a BA in physics and the philosophy of science and then a PhD in religious studies. After teaching in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he founded the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies to explore the integration of scientific approaches and contemplative methods.

More Books by B. Alan Wallace

Alan Wallace on The Seven-Point Mind Training

Here is an excerpt from The Seven-Point Mind Training.

The Measure of Having Trained the Mind

The fifth point concerns how we measure our progress in the Mind Training. What are the indications that the practice is working successfully?

All Dharma is included in one purpose.

Through hearing, reflection, and meditation, we explore the issue of personal identity and, as Sechibuwa says, we find upon investigation that this “I” as an intrinsic entity, existing in dependently of conceptual designation, is no more real than the horns of a hare. Since beginningless time, this illusion has brought us suffering and discontent. Seeking to be free of the suffering and to find greater meaning and fulfillment in our lives, we practice Dharma. Many of us have by now encountered a wide range of practices-breath awareness, mindfulness, loving kindness, the Lam Rim practices, meditation on emptiness, meditative quiescence, and even tantric practices. All these practices, all the teachings of the Buddha, all the commentaries, serve one purpose: to subdue self-grasping.

Through hearing, reflection, and meditation, we explore the issue of personal identity and, as Sechibuwa says, we find upon investigation that this “I” as an intrinsic entity, existing in dependently of conceptual designation, is no more real than the horns of a hare. Since beginningless time, this illusion has brought us suffering and discontent. Seeking to be free of the suffering and to find greater meaning and fulfillment in our lives, we practice Dharma. Many of us have by now encountered a wide range of practices-breath awareness, mindfulness, loving kindness, the Lam Rim practices, meditation on emptiness, meditative quiescence, and even tantric practices. All these practices, all the teachings of the Buddha, all the commentaries, serve one purpose: to subdue self-grasping.

We are now challenged to investigate for ourselves the quality of our lives, and to see how our actions of body, speech, and mind have influenced the level of our self-grasping. We may find that the practice is in fact enhancing the so-called eight mundane concerns—pleasure and pain, gain and loss, praise and blame, honor and dishonor. If our practice does not diminish self-grasping, or perhaps even enhances it, then no matter how austere and determined we are, no matter how many hours a day we devote to learning, reflection, and meditation, our spiritual practice is in vain.

A close derivative of self-grasping is the feeling of self importance. Such arrogance or pride is a very dangerous pit fall for people practicing Dharma. Especially in Tibetan Buddhism, with its many levels of practice, the exalted aspirations of the bodhisattva path, and the mystery surrounding initiation into tantra, we may easily feel part of an elite. Moreover, the philosophy of Buddhism is so subtly refined and so penetrating that, as we gain an understanding of it, this also can give rise to intellectual pride.

But if these are the results of the practice, then something has gone awry. Recall the well-known saying among Tibetan Buddhists that a pot with a little water in it makes a loud noise when shaken, but a pot full of water makes no noise at all. People with very little realization often want to tell everyone about the insights they have experienced, the bliss and subtleties of their meditation and how it has radically transformed their life. But those who are truly steeped in realization do not feel compelled to advertise it, and instead simply dwell in that realization. They are concerned not to describe their own progress, but to direct the awareness of others to ways in which their own hearts and minds can be awakened.

As Tibetan wisdom points out, vegetation does not grow on top of a high mountain, but grows luxuriously in the valleys; and, similarly, a person who feels superior to others learns very little from them and assumes they have nothing to offer someone so far above them. But a person who looks up to others, not just intellectually but from the heart, is ready to listen to their wisdom. And just as the valley accumulates the good top soil from above, so likewise this person is receptive to wisdom, again and again.

Although we all try to engage in spiritual practice according to our own abilities, it is very helpful to have some criterion by which we can estimate our progress. Here is the crucial test: how has our sense of personal identity been influenced? The stronger our self-grasping, the more easily it gives rise to irritation, anger, and resentment. It gives rise also to attachment, and actually forms the basis of self-centeredness. We can check the level of our own self-grasping by checking on the derivative mental distortions and obscurations that arise from its root.

On a more optimistic note, if we find that our practice results in decreased self-grasping, we can recognize its authenticity. This too distinguishes a true Dharma practitioner from one who is merely practicing a facsimile. Keep in mind that one can be a great scholar and articulate speaker, or spend many hours in meditation, without being an authentic Dharma practitioner at all.

The Seven-Point Mind Training: A Tibetan Method for Cultivating Mind and Heart, by B. Alan Wallace

Rounding Off the Practice: Preparing for Death

| The following article is from the Winter, 2012 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

The beauty of this Mahayana practice for the end of life is that it can be shared with friends and family who may not be Buddhist. This simple, five-aspected practice is adapted from

The Seven- Point Mind Training: A Tibetan Method for Cultivating Mind and Heart

At the end of a life devoted to Dharma, there comes a time for rounding off the practice. When we recognize that illness or simply old age has brought us very close to death, we can implement specific practices to influence the transfer of consciousness from this life to the next. The Tibetans have preserved a number of such practices, called phowa, working with energies associated with the transfer of consciousness. Most of these practices are taught in the context of Buddhist tantra, and they are often explained in relation to the bardo (the period following death and before the next life), as set forth, for instance, in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. But not many people are fully qualified to practice tantra.

The phowa practice based on the five powers presented here in the Mahayana context of the Mind Training is a non-tantric bodhisattva practice, which is more accessible for most people. We can keep this very practical and precious teaching in mind not only for ourselves, but also for loved ones who are not Buddhists, let alone advanced tantric practitioners. Reading the Tibetan Book of the Dead to a dying friend who is not interested in Buddhism will not likely be very helpful; sharing this practice may well be useful.