| The following article is from the Summer, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

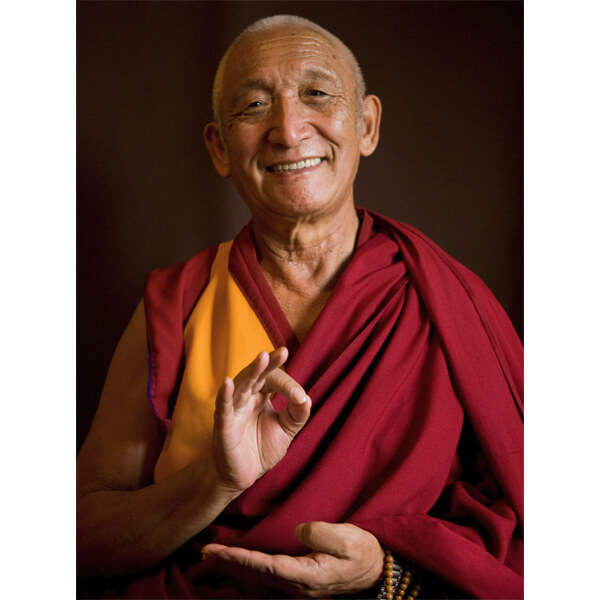

Geshe Sonam Rinchen

How do we free ourselves from the demon of self-concem? These instructions are found in Eight Verses for Training the Mind, one of the most important texts from a genre of Tibetan spiritual writings known as lojong (literally "mind training''). The root text was written by the eleventh-century meditator Langri- tangpa. His Holiness the Dalai Lama refers to this work as one of the main sources of his own inspiration and includes it in his daily meditations.

"Among the many brilliant texts that the collaboration of Geshe Sonam Rinchen and Ruth Sonam have produced, this one explains in clear terms how to implement the essential practices of compassion, which are so difficult to integrate into one's daily life. What a treasure!"—JEFFREY HOPKINS

"As a student of Geshe Sonam Rinchen, I can almost see his bright smile and hear his compassionate voice as I read this book. His practical and clear spiritual advice cuts to the core of our problems and shows us the way to resolve them."—BHIKSHUNI THUBTEN CHODRON

"Once more Geshe Sonam Rinchen has presented us with the authentic tradition of Tibetan Buddhism in this clear explanation of one of its most basic texts. I recommend it highly to all who wish to overcome the depression of self-pity through the development of deep concern for others."—ALEXANDER BERZIN, author

"Geshe Sonam Rinchen has masterfully invoked the full force of a traditional commentary to this classic mind training text that will challenge anyone sincere about confronting their egoism and transforming it into altruism."—TUBTEN PENDE, Director of Education, FPMT Buddhist Centers

Geshe Sonam Rinchen is resident scholar at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala, India, where he teaches Buddhist philosophy and practice.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter titled "The Treasure Trove."

Geshe Langritangpa suggests another way of dealing with provocative situations that cause the disturbing emotions to arise. In our normal everyday life we cannot avoid meeting people who are very difficult. When trying to forget about ourselves and cherish others, the kind of seclusion that we must seek in such situations is not to isolate ourselves physically but to distance ourselves from self-concern and self-interest.

When I see ill-natured people,

Overwhelmed by wrongdoing and pain,

May I cherish them as something rare,

As though I had found a treasure-trove.

When faced with ill-natured people, we should think about the fact that in the past they failed to see the harmfulness of the disturbing emotions which now overwhelm them. They became accustomed to giving them full rein and this familiarity has carried over into their present life. Nor can they have created much positive energy. All of this accounts for their unpleasant conduct.

There are so many people who are ungrateful for the kindness which others show them. Imagine you have cooked a delicious meal for a sick friend and you bring it to her. In her haste to eat she takes a big mouthful and burns her tongue. Angrily she pushes the plate away or worse still throws it on the ground. Such bad manners, so ungrateful! Our normal reaction would be to feel angered and swear never to do anything for her again. Many people indulge their disturbing emotions and do nothing to curb them. They don't see anything wrong with expressing them. It is as if they are running around stark naked, without the clothing of self- respect and decency.

There are people who commit horrifying ill-deeds, such as the five extremely grave and the five almost as grave negative actions. There are others who have broken their ordination vow as a monk or nun but still shamelessly make private use of what belongs to the spiritual community. This has always been considered very wrong. In a secular context, a similarly serious action would be to appropriate monetary donations or things given to an aid organization and use them for private purposes.

Then there are those suffering intensely from deforming, incurable or contagious diseases, just hearing the name of which makes us feel afraid. When we are faced with these three categories of people, we should not try to avoid or ignore them, pretend we haven't seen them or turn our backs on them. Instead of rejecting them and keeping as far away as possible out of fear or disgust, which we instinctively do, we should regard them with a sense of closeness and compassionately help them in whatever ways we can.

In the case of those who are doing wrong, we must consider what the consequences of their wrong actions will be and feel as sorry for them as we would for a man who has been condemned to death and who is being led to his execution. Concerning those who are sick, we should remember that their suffering is the consequence of past negative actions and a lack of merit. There is no knowing whether the momentum of those actions will come to an end in this life or whether they will have to endure further suffering in the future. To all of these unfortunate people we should speak kindly and compassionately and try to be helpful in stopping them from doing anything negative. If our advice falls on deaf ears, we shouldn't feel discouraged, but without harshness and without losing our kindheartedness we should continue to do what we can to prevent them causing further harm.

Others' stubbornness can be discouraging and exhausting. Our involvement with them seems to harm us and we would definitely prefer to have nothing further to do with them. The masters of this mind-training tradition urge us to avoid such thoughts at all costs, remembering how easily we could be in their place. Without being condescending, we should give practical help and in imagination take on their suffering with the wish that it should ripen on us.

People who are difficult to deal with offer us a precious chance to train ourselves to be loving, compassionate and altruistic, generous, ethical and patient. That is why they are like a precious treasure. A true practitioner feels responsible for steering them in a positive direction.

Shantideva says:

The beggars in this world are many,

Attackers are comparatively few.

For as I do no harm to others,

Those who do me injury are rare.

Ill-natured and hostile people allow us to practice the patience of willingly accepting difficulties and of taking no account of those who harm us. For this reason it is right to feel delighted when we come across them and to remember their kindness since, unintentionally, they help us along the path to enlightenment.

In fact we do not meet such challenges very often. If we knew there was treasure underground or on a ship that has sunk, we would go to enormous trouble to bring it up to the surface and would certainly take great care of our find. Encountering people who challenge us in these ways is like finding such a treasure. We should be prepared to invest time and energy because through our contact with them we can increase our capacity to be compassionate. This will eventually lead us to the spirit of enlightenment and all the ensuing benefits.

If we are constantly surrounded by nice people who treat us well and by those who are in good health, we will lack the opportunity to increase our compassion. Therefore, when such a rare opportunity presents itself, we must recognize its value and cherish it. In this way we use adverse circumstances to support our spiritual practice, which is a central theme of the instructions for training the mind.

Practitioners who are already quite accomplished may well find there are relatively few people in relation to whom they can practice patience because they are less easily irritated, but most of us find that there are a lot of annoying people around. The more self-preoccupied and egocentric we are, the more enemies we think we have because anything others do that does not accord with our opinions and views is considered an act of hostility. Even a small unintentional gesture is interpreted as a snub and everything that happens is evaluated only from our narrow egocentric perspective. This can make us feel quite paranoid. One thing is certain, however: if even the great Bodhisattvas manage to find enough people who give them the opportunity to practice patience, we ourselves will certainly come across many more.