Lay the blame for everything on one.

All suffering, all sickness, possession by spirits, loss of wealth, involvements with the law and so on, are without exception the result of clinging to the “I.” That is indeed where we should lay the blame for all our mishaps. All the suffering that comes to us arises simply through our holding on to our ego. We should not blame anything on others. Even if some enemy were to come and cut our heads off or beat us with a stick, all he does is to provide the momentary circumstance of injury. The real cause of our being harmed is our self clinging and is not the work of our enemy. As it is said:

All the harm with which this world is rife,

All the fear and suffering that there is:

Clinging to the ‘I’ has caused it!

What am I to do with this great demon?

When people believe that their house is haunted or that a particular object is cursed, they think that they have to have it exorcized. Ordinary people are often like that, aren’t they? But ghosts, devils and so on are only external enemies; they cannot really harm us. But as soon as the inner ghost of ego-clinging appears—that is when the real trouble starts.

A basis for ego-clinging has never at any time existed. We cling to our “I,” even when in fact there is nothing to cling to. We cling to it and cherish it. For its sake we bring harm to others, accumulating many negative actions, only to endure much suffering in samsara, in the lower realms, later on.

It says in the Bodhicharyavatara:

O you my mind, for countless ages past,

Have sought the welfare of yourself;

Oh the weariness it brought upon you!

And all you got was sorrow in return.

It is not possible to point to a moment and say, “This was when I started in samsara; this is how long I have been here.” Without the boundless knowledge of a Buddha, it is impossible to calculate such an immense period of time.

Because we are sunk in the delusion of ego-clinging, we think in terms of “my body, my mind, my name.” We think we own them and take care of them. Anything that does them harm, we will attack. Anything that helps them, we will become attached to. All the calamities and loss that come from this are therefore said to be the work of ego-clinging and since this is the source of suffering, we can see that it is indeed our enemy. Our minds, which cling to the illusion of self, have brought forth misery in samsara from beginningless time. How does this come about? When we come across someone richer, more learned or with a better situation than ourselves, we think that they are showing off, and we are determined to do better. We are jealous, and want to cut them down to size. When those less fortunate than ourselves ask for help, we think, “What’s the point of helping a beggar like this? He will never be able to repay me. I just can’t be bothered with him.” When we come across someone of equal status who has some wealth, we also want some. If they have fame we also want to be famous. If they have a good situation, we want a good situation too. We always want to compete. This is why we are not free from samsara: it is this that creates the sufferings and harm which we imagine to be inflicted on us by spirits and other human beings.

Once when he was plagued by gods and demons, Milarepa said to them: “If you must eat my body, eat it! If you want to drink my blood, drink it! Take my life and breath immediately, and go!” As soon as he relinquished all concern for himself, all difficulties dissolved and the obstacle-makers paid him homage.

That is why the author of the Bodhicharyavatara says to the ego:

A hundred harms you’ve done me

Wandering in cycles of existence;

Now your malice I remember

And will crush your selfish schemes!

The degree of self-clinging that we have is the measure of the harms we suffer. In this world, if a person has been seriously wronged by one of his fellows, he would think, “I am the victim of that man’s terrible crimes, I must fight back. He ought to be put to death, or at least the authorities should put him in prison; he should be made to pay to his last penny.” And if the injured man succeeds in these intentions, he would be considered a fine, upstanding, courageous person. But it is only if we really have the wish to put an end to the ego-clinging which has brought us pain and loss from beginningless time—it is only then, that we will be on the path to enlightenment.

And so, when attachment for the “I” appears—and it is after all only a thought within our minds—we should try to investigate. Is this ego a substance, a thing? Is it inside or outside? When we think that someone has done something to hurt us and anger arises, we should ask ourselves whether the anger is part of the enemy’s makeup or whether it is in ourselves. Likewise with attachment to friends: is our longing an attribute of the friend, or is it in ourselves? And if there are such things as anger or attachment, do they have shape or colour, are they male, female or neither? For if they exist, they ought to have characteristics. The fact is, however, that even if we persevere in our search, we will never find anything. If we do not find anything, how is it that we keep on clinging? All the trouble that we have had to endure until now has been caused by something that has never existed! Therefore, whenever the ego-clinging arises we must rid ourselves of it immediately and we should do everything within our power to prevent it from arising again. As Shantideva says in the Bodhicharyavatara:

That time when you could beat me down

Is in the past, it’s no more here.

Now I see you! Where will you escape?

I will crush your haughty insolence!

“In this short lifetime,” Geshe Shawopa used to say, “we should subdue this demon as much as possible.” Just as one would go to lamas for initiations and rituals to exorcize a haunted house, in the same way, to drive away this demon of ego-clinging, we should meditate on Bodhichitta and try to establish ourselves in the view of emptiness. We should fully understand, as Geshe Shawopa would say, that all the experiences we undergo are the fruit of good or evil actions that we have done to others in the past. He had the habit of giving worldly names to selfish actions, and religious names to actions done for others. Then there was Geshe Ben who, when a positive thought occurred to him, would praise it highly, and when a negative thought arose, would apply the antidote at once and beat it off.

The only way to guard the door of the mind is with the spear of the antidote. No other way exists. When the enemy is strong, we too have to be on the alert. When the enemy is mild we can loosen up a little bit as well. For example when there is trouble in a kingdom, the bodyguards will protect the king constantly, neither sleeping at night nor relaxing by day. Likewise, in order to drive away the mischiefmaker of our ego-clinging, we should apply the antidote of emptiness as soon as it appears. This is what Geshe Shawopa used to call “the ritual of exorcism.”

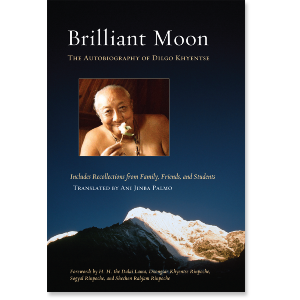

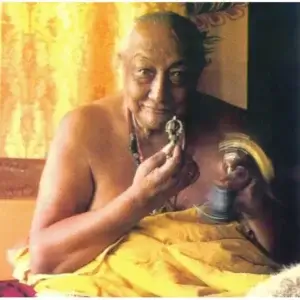

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910–1991) was a highly accomplished meditation master, scholar, and poet, and a principal holder of the Nyingma lineage. His extraordinary depth of realization enabled him to be, for all who met him, a foundation of loving-kindness, wisdom, and compassion. A dedicated exponent of the nonsectarian Rime movement, Khyentse Rinpoche was respected by all schools of Tibetan Buddhism and taught many eminent teachers, including His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He tirelessly worked to uphold the Dharma through the publication of texts, the building of monasteries and stupas, and by offering instruction to thousands of people throughout the world. His writings in Tibetan fill twenty-five volumes.

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910–1991) was a highly accomplished meditation master, scholar, and poet, and a principal holder of the Nyingma lineage. His extraordinary depth of realization enabled him to be, for all who met him, a foundation of loving-kindness, wisdom, and compassion. A dedicated exponent of the nonsectarian Rime movement, Khyentse Rinpoche was respected by all schools of Tibetan Buddhism and taught many eminent teachers, including His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He tirelessly worked to uphold the Dharma through the publication of texts, the building of monasteries and stupas, and by offering instruction to thousands of people throughout the world. His writings in Tibetan fill twenty-five volumes.