| The following article is from the Spring, 1998 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Moonbeams of Mahamudra

by Venerable Khenchen Thrangu, Rinpoche, translated by Ken McLeod. 120 pp. #MOMA $12.95 August

Moonbeams of Mahamudra presents a direct meditation on the mind that has led thousands of practitioners to complete enlightenment, in one lifetime. It begins with a detailed explanation of shamatha and vipashyana meditation and then shows how these basic meditations differ in the mahamudra practice. Shamatha meditation trains the mind to rest upon a single point whether the object is the breath or the mind itself. Vipashyana meditation in mahamudra is the realization of the true nature of reality which is emptiness of the individual and all phenomena. Thrangu Rinpoche explains the nature of emptiness in detail and describes how the meditator can arrive at this realization by looking directly at mind. When this is done with repeated effort, the meditator sees through the mistaken appearances of mind and sees how mind really is luminous clarity. This is the essence of mahamudra meditation.

For a book to explain the profound philosophical issues of Buddhism as well as give deep insight into meditation, it requires an extraordinary author. Thrangu Rinpoche is such a person, being a practitioner of Mahamudra meditation for over forty years and such a great scholar that he was asked to establish the Kagyu monastic college in Rumtek for His Holiness the Karmapa, head of the Kagyu lineages of Tibetan Buddhism. Bom in eastern Tibet in 1933, he was recognised as the reincarnation of the great Thrangu tulku. He received a traditional monastic education and achieved his geshe degree at age 35. Thrangu Rinpoche became the personal teacher of many important lamas. He has also engaged in over fifteen years of teaching Western students in seminars and retreats in over a dozen countries. He is well-known for taking complex teachings and making them understandable to the practitioner. This book came out of one such intensive seminar on mahamudra given in Big Bear, California.

Other books by the same author: Buddha Nature, The Four Ordinary Foundations of Buddhist Practice, King ofSamadhi, The Th ree Vehicles of Buddhist Practice, Uttara Tantra.

Following is an excerpt from Moonbeams of Mahamudra entitled What is Mahamudra?

Mahamudra is a teaching, an instruction derived from Buddhist teachings based on the material which the Buddha taught in the sutras. It is also derived from the practice in the vajrayana tradition. In the vajrayana, the tantric tradition, we have the four levels of tantra, of which the liighest, most sophisticated form of application is the supreme yoga tantra (Skt. anutlarayoga tantra), and the mahamudra approach is derived from the teachings of this particular section of the tantra Finally, mahamudra is not only based on the sutras and tantras, it is the very essence, the pith of the sutras and tantras, which is all that the Buddha taught.

The Term Mahamudra

The term mahamudra is a Sanskrit word composed of two syllables: maha meaning great and mudra which in this context means seal as in the seal a king puts on letters and proclamations. Mahamudra is explained in many different ways. One of the traditional ways describes mahamudra as ground, mahamudra as path, and mahamudra as fruition with the most important being mahamudra as ground referring to the ground of our experience. Mahamudra in this context means the nature of mind, or how the mind is. The mind, in essence, is empty. There is nothing which is established as an object or as a thing having substantial nature. The natural expression of mind, however, is luminosity, often called clarity. So we have the clarity which has no substantial nature whatsoever. It is empty and arises unceasingly. These are the three traditional characteristics of mind: its essence being empty, its nature being clarity, and its manifestation being unceasing.

Mahamudra as ground refers to how the mind is. In understanding how the mind is, we understand also how all phenomena, the constituents of our experience, are. Phenomena also have no intrinsic reality and are empty. This is why the metaphor of a seal is used. When a monarch makes a proclamation, for that proclamation to have the full weight of the royal authority behind it, the king applies his seal. He doesn't need to apply his seal to each separate paragraph but simply to the end of the document. In the same way, phenomena are empty, luminous, and unceasing. Our mind is also empty, luminous, and unceasing. In understanding this, we understand everything. It is not necessary to understand that each particular dharma is empty because once we understand how our mind is empty, we understand everything or the nature of all phenomena. So this is why the term mahamudra or great seal is used.

These are the three traditional characteristics of mind: its essence being empty, its nature being clarity, and its manifestation being unceasing.

Perhaps it will be helpful to look at the various philosophical perspectives of Buddhism very briefly to see how these positions fit with mahamudra. If we contrast the Themvada or hinayana viewJ and the mahayana view, the hinayana sees things in terms of truth. For instance, the goal to be achieved in the hinayana is understanding the Four Noble Truths. The basic hinayana perspective is the feeling that the world exists in some way and we need to discover the truth about the way the world exists. Part of this belief is the fact that we don't exist as a self.

In the mahayana view, however, the emphasis shifts considerably focusing not so much on realizing truth as on understanding the perspective that all phenomena lack intxinsic existence. This understanding needs to be developed experientially. So, rather than focusing on the understanding of the Four Noble Truths, we focus on the understanding of emptiness and hence the deceptive way in which phenomena appear to us. In the particular branch of mahayana known in Tibetan as shentong, we could say the role of emptiness is slightly de-emphasized and more emphasis is put on the idea of buddha nature. This idea is that while buddhanature is essentially empty, it carries the full potential of all of the magnificent qualities ol a fully awakened Buddha with an emphasis on the unfolding of those qualities.

In the vajrayana the emphasis again shifts and the focus attention turns much more inward to understanding how the mind actually is, what the fundamental nature of mind is. With the experience and understanding of the fundamental nature of mind, one understands experientially the emptiness of all phenomena. This is essentially the focus of mahamudra.

The Essence of Mahamudra

Very simply, the essence of mahamudra is mind as it is. How is the mind? We may try to associate mind with some kind of characteristic such as color, shape or form, but we cannot associate any real characteristic with it. We may even try to say mind exists. But the status of existence is very difficult to ascertain, as the Third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje says in his Aspirations of Mahamudra:

It is not existenteven the victorious ones have not seen it.

It is not nonexistentit is the basis of all samsara and nirvana.

This is not a contradiction, but is the middle path of unity.

May we realize the true nature of mind, which is free from extremes.

It doesn't exist, even the buddhas have not seen it. There is simply nothing which can be experienced as an object, there is no basis for existence in this way. However, the mind is the basis for the totality of our experience. Everything that we experience arises from mind. Our whole experience of samsaric existence is an expression of mind. And the experience of nirvana, of freedom and liberation, is also mind. This is why Rangjung Dorje wrote in the next line of that prayer, It is not nonexistent because it is the basis of all samsara and nirvana. Difficult as it may seem to reconcile these two, this is how the mind is. And that is why this prayer refers to mahamudra as the ground. The term mahamudra is generally referred to as the way things are or dharmata. However, we don't just one day look and see our mind as it really is because there's a lot of meditation practice associated with mahamudra. We meditate in certain ways and make changes in the progression of meditation associated with mahamudra. Loosely speaking, we also refer to this system of meditation as mahamudra. There are also a lot of teachings and instructions on mahamudra that delineate precisely the various subtle points and philosophy and so forth. These teachings collectively are also referred to as mahamudra. So we have mahamudra as the way things are, mahamudra as a meditation system, and mahamudra as a body of instruction. But the principal meaning of mahamudra is simply as the fundamental nature of the way things are.5

1. The vajrayana is divided into four different classes of tantras. The first is the action tantra (kriyatantra) which emphasizes external ritual, the performance tantra (caryatantra) which has an equal emphasis on both internal meditational and external ritual, the union tantra (yogatantra) which emphasizes internal meditations, and the highest yoga tantra (anuttarayogatantra) which, in part, concentrates on examining mind directly.

2. The Tibetans traditionally divide the Buddha's teachings into three levels. The hinayana teachings which are primarily teachings on shamatha and vipashyana meditation with an emphasis on the Four Noble Truths. These practitioners are found predominately in Thailand, Burma, Sri Lanka and work for the goal of achieving complete control over self and their ideal is an arhat.

The second level, the mahayana practitioner places emphasis on compassion and liberating all sentient beings. The mahayana practitioners are found predominately in China, Japan, Korea and practice the six paramitas and have the bodhisattva as an ideal.

The third level, the vajrayana practitioner places an emphasis on practices of the tantra and the thorough study of mind. These practitioners are found primarily in Tibet and Mongolia.

Thrangu Rinpoche has always emphasized that these levels are not higher or lower in terms of their being better or worse. Rather everyone must begin with the fundamental hinayana practice and whether they go on to the mahayana or vajrayana depends entirely upon their inclination and diligence.

3. Rongtong and Shentong are two different schools in Tibet that disagree about how to interpret emptiness in the middle way or the Madhyamaka. Rongtong literally means self emptiness and advocates the inherent existence of all phenomena. This school bases its interpretation that absolutely all phenomena is empty and is based on Nagarjuna's Slamkaya treatise and this position was adopted by such great scholars as Tsong Khapa, the founder of the Gelug lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. Thrangu Rinpoche in this commentary usually takes the side of the Shentong school which bases its doctrine on emptiness on Nagarjuna's Yuktikaya treatise. The Shentong or literally other emptiness school believes that there is luminosity in emptiness.

Thrangu Rinpoche says, In the Shentong school the greatest emphasis is put on buddha nature. Now some teachers in the past have regarded the teaching of buddha nature because it is present in everyone as being basically identical with the self or ego of an individual. They said this is an incorrect view and have refuted it. But their refutation is based on an incorrect understanding of the Rongtong position of buddha nature. The Rongtong position holds that when it's properly understood, buddha nature is itself empty. Without buddha nature being empty it does simply become another form of self which has all the problems that any concept of individual self has which has been refuted many times in all the schools. So most teachers find that this Rongtong position is a more powerful and more sophisticated view. But if it's not properly understood, then it's actually wrong. The Madhyamaka school clearly presents the concept of the egolessness of self. There's been a long tradition of debate and logical argument in the Tibetan tradition which has gone on for hundreds of years and it goes back to the Indian tradition. The purpose of this debate between various positions was to create a constant evolution, so that any problems in a particular view was uncovered and then could be corrected. The function of the debates between the various philosophical traditions is to sharpen the understanding of the participants and of the view that individuals expressed by that particular tradition. So it really comes down to that if buddha nature is misunderstood as a self, then yes, it is quite incorrect. But if buddha nature is understood to be empty itself, then the perspective of Rongtong is generally regarded as more powerful. The understanding that everything is empty the same. The view of buddha nature just seems to be a bit more helpful than the view that there is nothing.

There are a lot of professors who have spent a great deal of time studying the dharma and have written many learned commentaries on it. But very, very few of them have had any real practice, so none of them really knows what he or she is talking about. As a result, a lot of what they write is simply wrong, so take care concerning this.

4. The Shentong school believes that all sentient beings possess an essence called buddha nature (Skt. tathatagarba, Tib. de shin shek pay nying po). Because they have this essence, they all have the potential to achieve Buddhahood.

5. To expand upon this, the Buddhist belief is that we as ordinary (unenlightened) beings don't see the world as it really is, but as an illusion. As already discussed in footnote 6 and footnote 8 our mind creates solid, real things, such as a hand, out of what is really something that is empty. Since it is our mind which creates this external delusion we call samsara, when we truly perceive and thoroughly understand how our mind works or is, then we finally see the external world as it really is or nalug? in Tibetan. The world as it really is called dharmadhatu in Sanskrit with dharma in this context meaning phenomena as it truly is and dhatu meaning a sphere or realm. So dharmadhatu or as it if often called dharmata can be translated as the sphere of reality. This dharmata can only be perceived by an enlightened individual. In the next section this is described in more detail in terms of how things are and how things appear.

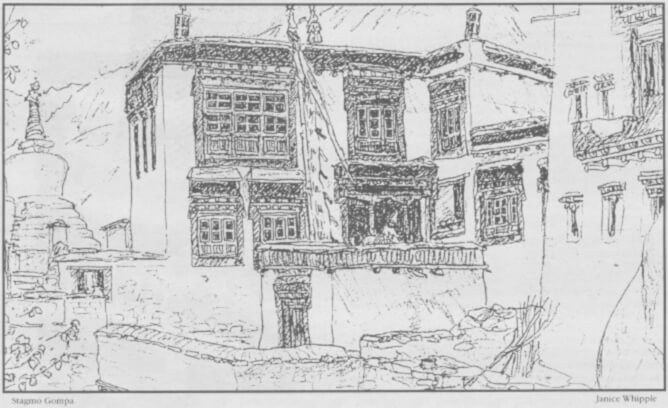

Pilgrimage to Traditional Ladakh

July 10 ~ 30, 1998

led by Karma Leksbe Tsomo

scholar, explorer and author of Buddhism Through American Women's Eyes and Sakyadita: Daughters of the Buddha

Insight Travel

(937) 767-1102 (800) 688-9851

for our other pilgrimages, visit our website at www.insight-travel.com