| The following article is from the Spring, 1989 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

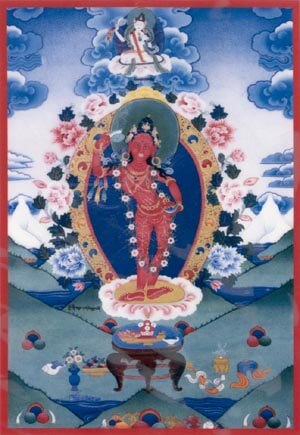

In her human form Yeshe Tsogyal is depicted as being white in color and in union with Padmasabhava. In her deified form, as Dechen Gyalmo, she is visualized red in color, standing alone, and devoid of clothing save jewelry made of flowers, pearls, and bone. As such she represents the blissful (female) quality of the enlightened mind that arises in conjunction with the empty (male) aspect of enlightenment.

Enlightened beings are said to emanate in three forms (kayas) in order to benefit beings of various levels of consciousness. The most subtle form is the pure, empty state of enlightenment, the Dharmakaya. From that state an enlightened being may emanate in the Sambogakaya form, embodying the radiant, energetic quality that naturally arises out of emptiness. In order to appear in a tangible form that most beings of ordinary consciousness can readily perceive, emanations often appear in the substantial state of the Nirmanakaya form.

Both Yeshe Tsogyal and Dechen Gyalmo are said to be Nirmanakaya emanations of Kuntuzangmo, the primordial female Buddha (Dharmakaya). In the practice found on a recording, by the anis of Sangchen Mingye Ling, a terma of Jigme Lingpa, founder of the Longchen Nying Thig school, the Sambogakaya level of the deity appears as Dorje Phagmo, a red, semi-wrathful female with a sow's heads emerging from the back of her neck, visualized as the wisdom deity existing in Dechen Gyalmo's heart. All these emanations are regarded as both the mother (or generative state) as well as consort (or coemergent state) of all Buddhas. Additionally, in this practice, the one hundred peaceful and wrathful deities said to appear to one in the bardo state after death are visualized at specific points within Dechen Gyalmo's body.

Within the Longchen Nying Thig lineage individual monasteries developed slight variations regarding melodic material, hand gestures (mudras), and the inclusion of auxiliary prayers. The form of the Dechen Gyalmo Puja found on this recording is in the tradition of Tso Patrul Rimpoche, an early twentieth-century lama residing in Eastern Tibet.

The Chod Ritual is a purification practice performed by many of the Vajrayana lineages. Designed to undercut attachment to the physical body, the ritual involves the visualization of the wrathful goddess, Tro-ma, who decapitates the practitioner, then offers a nectar made from the body to friends and enemies. Usually performed at night, often in desolate places such as cemeteries, Chod is not necessarily linked to the Dechen Gyalmo Puja. However on the particular date of recording, this version of the Longchen Nying Thig Chod Ritual was performed as a finale to the puja.

Dating back to the establishment of Tantric Buddhism, when Yeshe Tsogyal become holder of Padmasambhava's lineage of teachings, women practitioners have been regarded as spiritual and intellectual equals of their male counterparts. As yogic consorts women have been considered essential members of their religious communities.

However, the overlay of traditional socio-economic values dictated that the majority of Tibetan women take on the role of servile homemakers. Prior to the Chinese Revolution, most Tibetan women were neither provided with an opportunity for literacy nor sufficient time for serious practice. Even today, despite some efforts towards feminization, especially in the area of education, many Tibetans retain their age-old customs. Women are commonly observed herding yaks, preparing fields, lugging huge, wooden buckets strapped to their backs, and preparing meals over fires fueled by patties fashioned by hand from yak dung and straw. Older children are left to their own devices and young infants tucked into the folds of loose-fitting robes so that any snatches of spare time may be spent circumambulating holy places.

Should a Tibetan woman have a desire to focus more seriously on Buddhist practice, her most culturally acceptable venue is to take the vows of nunhood.

The anis of Sangchen Mingye Ling are a group of women who have made this choice. They are headed by a small number of older nuns who, prior to the Cultural Revolution, were students of the yogi and scholar, Tso Patrul Rimpoche. During the Cultural Revolution these women externally took on low profile life-styles, some marrying and having children, but secretly retained their passion for Dharma. With the recent return of more liberalized attitudes toward ethnic culture and religious practice in the People's Republic, the older anis were able to renew their vows. In addition a number of younger women have become attached to their group; currently there are approximately forty anis in all, ranging in age from early teens to their late eighties. The oldest and most revered of the elder generation passed away in 1986, demonstrating signs of full realization at her death.

Attired in traditional fushia and maroon robes, the anis reside together in small adobe houses resembling those of the Southwest Indians. Their homes are also used as places of worship and retreat. Falling outside the usual means of support, as they are neither members of nuclear families nor government employees, these women live a very minimal existence, relying on what family members have to offer, and are often reduced to taking odd jobs in the community. It is not unusual to see a small group of anis walking down a street loaded with piles of hay the size of two bales on their backs. In addition to regular Nyingma practices, the anis, in part as a way of cutting food costs, frequently perform the strenuous Nyung Nye practices, which limit food intake to one meal every two days. Yet even with these hardships the anis of Sangchen Mingye Ling are jubilant in their devotion, a devotion movingly expressed in this recording made of their practices. Available on cassette from Snow Lion.