| The following article is from the Summer, 1997 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

b y Blake Kerr

y Blake Kerr

photos by John Ackeriy

foreword by H.H. the Dalai Lama

212 pp. #SKBU $12.95 September

Sky Burial is the distilled truth alternately tragic, hilarious and rousing of two young Americans' exposure to the joyous spirit of the Tibetan people and their courageous struggle to survive under the brutal subjugation of Chinese communist rule. It is a vivid portrait of a critical moment in Tibet's modern history. An evocative, endearing, and invaluable book.

—John Avedon, author of In Exile from the Land of Snow.

Having just graduated from medical school, Blake Kerr convinces his old college friend, John Ackeriy to travel by plane, train and bus to Lhasa. They meet an assortment of colorful characters in Tibet's capital and then hitchhike to Everest, where they hump loads for an American expedition assaulting the mountain.

Upon returning to Lhasa, Kerr and Ackeriy swiftly become aware of the oppressive character of the Chinese occupying forces. They witness a series of demonstations by Tibetan protestors, which are brutally quashed by Chinese police and armed forces.

Kerr and Ackeriy attempt to aid the rebels, but are arrested and endure a brief, harrowing imprisonment. They successfully alert the international media to the tragic events and become activists committed to ending China's oppression after their forced departure from Tibet.

This is the best account of the 1987 Tibetan uprising against Chinese police control in Lhasa and the subsequent crackdown on dissent. Blake Kerr captures the beauty, terror, and tragedy of Tibet.Washington Post

Merchant-Ivory Productions have purchased the movie rights for Sky Burial.

Here is an excerpt from Sky Burial:

The clouds stole the light back from the mountains as quickly as it had come. Suddenly the bus hit a bump that launched passengers into the luggage racks over their heads. Moans and obscenities in several languages filtered up to our seats in the front of the bus. A Chinese man wearing a full-length green army coat pulled his ashen face inside his window. He looked like he might throw up again at any moment.

Patrick, a loyal British subject on a three-week holiday from teaching English in Yunnan Province, also looked ill. I gave him some aspirin and my water bottle and asked him to offer them to the Chinese man. The man did not take the aspirin, but he wanted to talk. According to Patrick, the government had offered the man work in Tibet at double the wage he could have earned in the mainland. He also could apply for government loans to start a business, and his children would be guaranteed a place in school.

We should be hitchhiking, John said, staring out the window.

We got out of shape riding soft-sleeper, I said, referring to China's trains.

First class! Patrick said, with the flair of an Elizabethan actor. That's traveling in a style more befitting gentlemen in your professions. Patrick said the Chinese army was brilliant to have built the road we were on with polypropylene, which would withstand the area's temperature extremes.

The PLA built the Friendship Highway' in the mid-1950s to invade Tibet, John said.

Where did you get that misinformation? Patrick asked.

It's in the Tibet guidebook, John said.

Do you believe everything you read in the guidebook? Patrick challenged. I've been in China for a year. The People's Daily has frequent articles on a number of socialist reforms and development in Tibet.

John and Patrick argued whether the People's Daily was a propaganda tool of the State. I grew tired of the sound of these two Westerners arguing out of ignorance and boredom, fueled as much by being cramped into the same bus for days than by anything either of them had experienced or read. I wondered if after four decades of occupation the Chinese were still liberating Tibet; many of the vehicles on the Friendship Highway carried soldiers.

The first bus in our convoy charged up an unpaved section of road and slid, wheels spinning, into the mud. As soon as our forward motion stopped, queasy passengers dashed off the bus to vomit, the typical beginning to a communal bathroom break. Men relieved themselves by the side of the road; women sought what shelter could be afforded behind a tuft of grass or hillock. The second bus swung wider than the first and plowed ten feet farther into the furrows from previous tracks. After consulting with the two other drivers, our bus driver then veered even farther from the roadand deeper into the mud.

Livid passengers cursed at the Chinese drivers for getting all three buses stuck at the same time. The worst drivers in the world, an Italian man shouted from the front of the bus. A Frenchman wearing thick glasses agreed: You'd think the Chinese would have learned to drive.

On the contrary, Patrick said, rising to the drivers' defense. These men are masters of the sodden road. More times than not they have saved us from becoming mired in this godforsaken baskerville. When the Frenchman shouted obscenities at our driver, Patrick resorted to ad hominem attack: You're blind as a bloody mole with those glasses. I'd like to see you do better.

Fuck you and your imperialist country.

Why don't we get out and see if we can help? Patrick said.

Without anyone's help, the drivers quickly hooked a braided steel cable to the front of the first bus. Patrick directed fifty people to line up on either side of the cable. Another fifty people surrounded the bus. With Patrick shouting encouragement to members of the myriad nations who pushed, pulled, and kicked each bus in turn, none moved.

Bloody hell, Patrick yelled. We're all bloody stuck.

When all efforts to extricate any of the buses from the quagmire failed, travelers resumed their verbal assault on the drivers. Patrick continued his defense of the Chinese drivers, populace, and government. Two hours later, two young soldiers who came by in an army truck towed each bus back onto the People's Highway.

We stopped in the late afternoon at Wenquan, the world's highest town at 16,830 feet. Some of the passengers yelled Zou! Zou! Zou! (Go! Go! Go!) Wind howling through the valley gave a lonely, desolate air to the place. A dog chained to a shelter of corrugated tin barked at two Chinese children, who pelted it with rocks. The dog frothed at the mouth and lunged at the children, only to be jerked back by the chain, which seemed as if it would snap at any moment.

When a Chinese man emerged from a run-down cinderblock building and handed the driver an envelope of money, which the driver counted, he said that we had to pay fifteen yuan (three dollars) each to stay the night. This is extortion! Patrick said. Hotels cost five yuan. We have daylight left. If we stay here, we will never make Lhasa tomorrow. I told Patrick that he could also die at this altitude. Patrick pleaded with the driver to continue to the next village. He became furious when the driver left the bus.

Zou! Zou! Zou! Patrick shouted. Other passengers joined in, tourists alongside Chinese immigrants, chanting, Zou! Zou! Zou! which reverberated inside the bus and drew in people from the other busses. Zou! Zou! Zou! until the sun slipped behind a hill and the temperature dropped below zero. Two Frenchmen pulled out sleeping bags inside the bus. The rest of us paid fifteen yuan each and were led into the hotel's dark rooms, where the bunk beds smelled of mildew.

Outside, near the icy chatter of the river, John and I talked about Robert Ford, the only Westerner living in eastern Tibet when the Chinese invaded. In 1949, Ford sent coded radio messages from Wenquan to monks in Lhasa. His last transmission on March 10,1949, simply said: The Chinese are here. Several months later, Ford was captured by the Chinese and accused of being a British spy. He spent the next five years of his life in jail.

John was a talking guidebook, and he shared with me his enthusiasm for the Yangtze River, tumbling out of the nearby glaciers to wind 3,430 miles through China, farther than any other river in the world except for those draining into the Nile and the Amazon. Tomorrow we would be in the Brahmaputra River drainage system, which emptied into the Ganges and flooded the plains from Calcutta to Bangladesh, and the Mekong River drainage system, which fanned out through Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam into the South China sea.

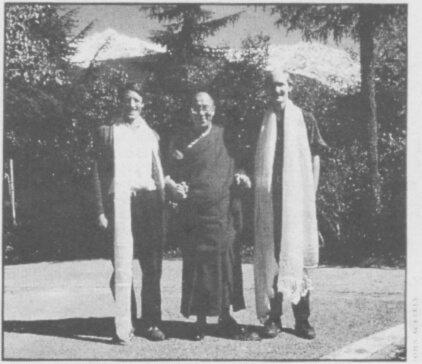

[Photograph: Blake Kerr, left, and John Ackeriy, right, with the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India.]

The next morning three tall, stoic men waited by the bus. They wore long sheepskins and daggers tucked into rope belts. Red tassels braided into their hair and wrapped around their heads enabled John to identify them as Khampas, from eastern Tibet. By reputation Khampas were a hardy people who had waged the most determined armed struggle against the Chinese in the 1960s. John pointed out that Khampas continued their isolated attacks on army convoys even after 1972, when Nixon and Kissinger formally halted the CIA funding of the Tibetan resistance.

After everyone else had boarded, the driver let the Khampas sit in the last row. Altitude sickness, and being launched into the roof each time the bus hit a pothole, had proved too much for five of the Chinese immigrants, who had not gotten back on. The Khampas sang and laughed each time their heads hit the roof. This annoyed some of the other passengers, but I was in awe of these proud people. I also made sure to get off the bus every time they did, to make certain our packs did not disappear. By reputation, Khampas are also bandits.

Thunder rattled the bus windows and the pit of my stomach, thunder that we learned later, turned out to be the Chinese Army using artillery to liberate the monsoon from the clouds.

Rock cairns with strings of faded prayer flags marked the Tanggula Shankou pass, the highest point in our trip. Two more people threw up. I heard Patrick moan as we crossed China's official border into the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

Each bend in the Lhasa Valley's patchwork of barley fields awaiting the harvest, each expanse of steel scree and magenta slope beneath an amphitheater of cliffs, each snowcapped mountain that tore at the indigo clouds seemed more magnificent than the last. The cramps from the two-day bus ride were forgotten as we approached the ancient city. Guidebooks appeared as passengers tried to decide which hotel they would try. As if by magic, thunder from the low-lying clouds accompanied our first glimpse of the Potala Palace rising majestically above the cinderblock buildings. Thunder rattled the bus windows and the pit of my stomach, thunder that, we learned later, turned out to be the Chinese Army using artillery to liberate the monsoon from the clouds.