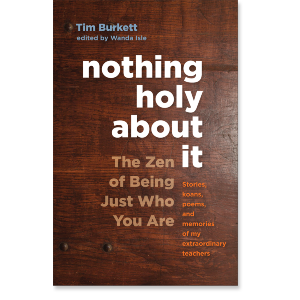

Excerpt from

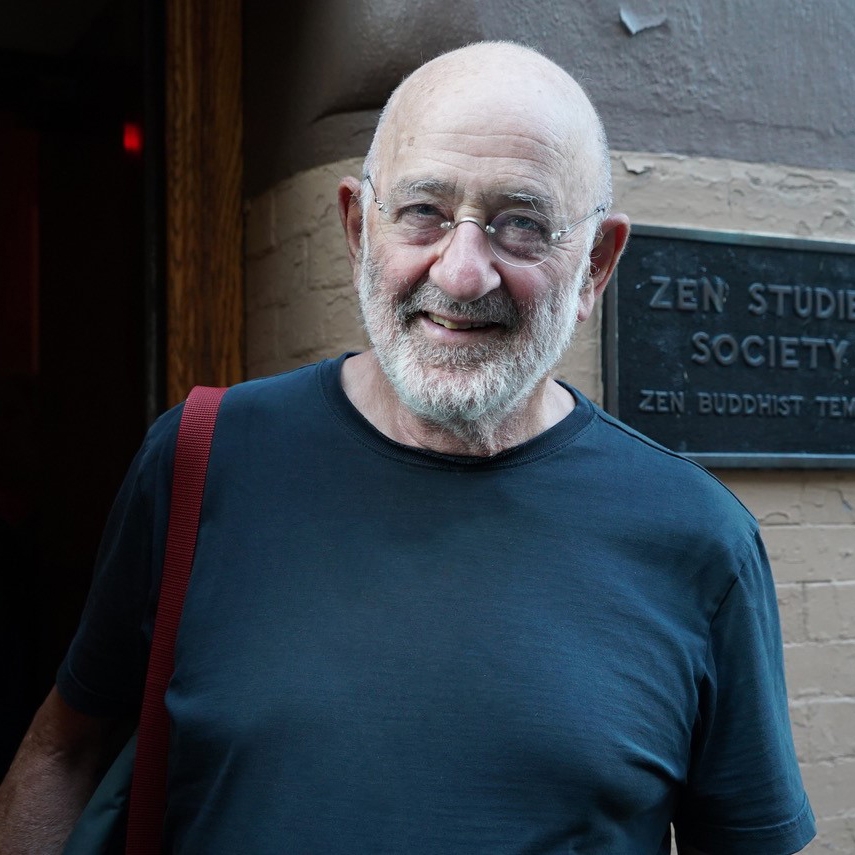

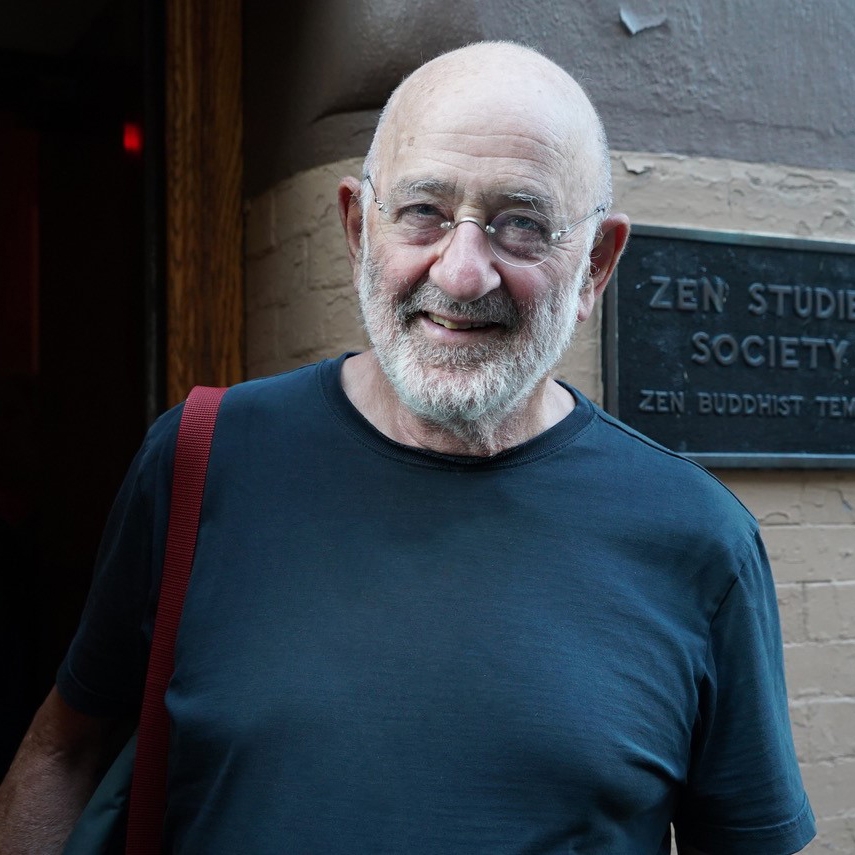

Lawrence Shainberg

Lawrence Shainberg is the author of the celebrated Zen memoir Ambivalent Zen as well as the nonfiction book Brain Surgeon: An Intimate View of His World. He has published three novels—Crust, One on One, and Memories of Amnesia—and his fiction and journalism have appeared in Esquire, Harper's Magazine, Tricycle, and The New York Times Magazine. He is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize for a monograph on Samuel Beckett, published in The Paris Review.

Lawrence Shainberg

GUIDES

Zen, Writing, and Studying Brain Damage

I go to sleep early but wake in a panic, realizing at once that Roshi’s talk is simmering in my mind. No label—not “anxiety,” not “terror,” not even “panic”—seems right for my condition until it occurs to me that this absence of label is exactly the point. I have directly experienced the emptiness that was as always his principal subject. It is beyond labels, beyond description and understanding, because it is beyond the dualistic mind.

Insights come in a rush. I go to my desk, open my word processor, and write a series of notes on emptiness. Pause, reread what I’ve written, and delete it with disgust. Put my computer to sleep and go to my cushion. My agitation grows, but the more I breathe into it—accept it—the more it seems like clarity.

Next morning, I phone Roshi to ask for a meeting. Though he’s tired and still jet-lagged, he is agreeable, suggesting tea that afternoon. Awaiting our meeting impatiently, I alternate between sitting and working at my desk, struggling in vain to find a way to talk about the emptiness I experienced, and, convinced that I’ll work out my contradictions with him, amazed at the good fortune that makes him so accessible to me.

As usual, the kettle is on the stove when I arrive, the table set with cups and saucers and a bowl of the Pepperidge Farm cookies he’s favored since coming to New York.

“Hi, Larry-san.”

“Hi, Roshi. How are you?”

“Dizzy! Tired. Sleep maybe two hour last night.”

He shakes the kettle, removing the top to see if the water is boiling yet. “Larry-san?”

“Yes, Roshi?”

“What happen your posture? Last night, back bent, head down! Look weak! Discourage! Many times I tell you—back bent, thought come. Chin down, mind become dark! What happen to you?”

“I don’t know, Roshi...I’ve been sitting a lot, but—”

“Sit like that, you wasting lot of energy! Back bent, anus open. I tell you many times, much thought come through anus! Spine straight, anus close, I guarantee—no thought come.”

“I know, Roshi. I know. But sometimes, I guess, I—”

“When you breathe, you all out or only part?”

“What?”

“How you say, ‘exhale’? Must not all. If air all out, thought come! Better you keep a little. No space, no thought! You want tea?”

“Yes, please.”

Taking a chair, I feel disoriented. It isn’t just that, as usual when I meet with him, I’ve forgotten what I meant to talk about. It occurs to me as if for the first time that I’ve chosen a teacher for whom thought’s arrival in the brain is considered an unfortunate development. How can I be surprised that, more and more often, when I take my seat on the cushion, I feel I’m leaving my work behind?

I tell you many times—don’t keep anything! Beautiful zazen, don’t keep. Terrible zazen, don’t keep. Stand up, let go. Good part forget, bad part forget.

Using a bamboo strainer, he spoons tea from a silver can I recognize. This is high-quality sencha, grown on a small farm owned by the monastery. When I’d lived there—for a month—two years before, I’d joined the training monks to help in its harvest. Six days on hands and knees, picking it leaf by leaf, like mowing a lawn by hand. Like so much Zen practice, a great test for one’s boredom threshold. No other tea cleared my head so quickly or better helped my zazen. One sip now reminds me why I’d called him this morning.

“Roshi?”

“Yes?”

“I’ve got to talk to you about something important.”

“Sure, sure. What?”

“More and more, it seems to me my work contradicts zazen. It’s like a power struggle, an impossible contradiction. If I pursue my work, I’m no good as a Zen student, and if I’m serious about Zen, I’m no good as a writer. Once and for all, I’ve got to decide where I stand. My work takes me away from Zen, and Zen takes me away from my work. I’ve got to give up one or the other. Stop writing and go to the monastery, or stop sitting and devote myself to writing.”

Roshi shook his head. “Stop?”

“Yes, one or the other!”

“Larry-san?”

“Yes?”

“I tell you many times—don’t keep anything! Beautiful zazen, don’t keep. Terrible zazen, don’t keep. Stand up, let go. Good part forget, bad part forget. Both forget! Just this is all! Not so easy, I know. It’s easy to practice Zen on a cushion. Five thousand times more easy than off. Stand up, you practice. Eat, you practice. Shit, you practice. Let go, just this, take it! Everything practice! Wonderful zazen, terrible zazen, please don’t complain, don’t analyze, just take it. If you patience, I guarantee you can do it! No need hesitate. Must believe yourself. If cannot believe yourself, cannot believe Buddha. Cannot believe God. Happy come, thank you very much! Pain come, thank you very much! You and pain, good relationship! Bad writing, thank you very much! Good writing, thank you very much! Maybe you think I’m talking joke. No, I only talk my own experience.”

“I know, Roshi. I know. From the point of view of Zen, I get it. But when I sit down to write, I hit the wall. It seems to me that no work in the world is further from Zen than writing. I’m happy when I practice, but how can I go all the way with it if I don’t give up writing once and for all?”

“Give up?”

“Yes! Once and for all!”

Roshi pushed the cookies toward me. “More cake?”

“No thanks, Roshi.”

“More tea?”

“Yes, please.”

“Larry-san, I tell you many times your problem—you attached to emptiness! Formless, empty, good, bad, forget it! Don’t keep any mind! If you thinking empty mind, you have partner. Already empty mind become dust mind. If you thinking something, you have picture inside your brain. Then can think! Zazen not only meditation. Your daily movement, meditation; your activity, meditation. Sitting time, just sit. Writing, just write. No need mix up. When you shit, you wipe anus, no? Then flush paper, no? No need keep paper, walk around shit in your pocket. Back straight, no problem! Too much thought, you ’fraid can’t sleep, mind dark, sad, become mental sick. I think you have idea of emptiness. Therefore, can attach. Aim for emptiness, like target. But please you understand, Larry-san—target not outside you. You and target, no distinction! No way you can miss!”

My brain damage novel would be published as Memories of Amnesia in 1988, but it had a long way to go before that. Naturally, my first burst of excitement was short-lived. There were moments of clarity, but they never lasted more than a couple of paragraphs. I was always in pursuit of the experience of acceptance that Eido Roshi had triggered. It was clear to me that it had been a nondualistic experience—which my brain, inherently dualistic, always compromised—but I could find no way around the fact that I needed dualism to write the book. This made it a manic-depressive experience, but I tried my best to take this as its virtue. From a book that aimed at differentiation from the brain, how could I ask for anything better than bipolarity? How be surprised that I was less coherent every day? If I meant the book to acknowledge the discontinuous truth I experienced in meditation, I had to expect discontinuity within my sentences as well as between them.

What saved me from this nightmare was a seminal instruction by the great Zen patriarch Eihei Dogen. “To study Zen is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self.” I’d been familiar with this teaching since my earliest days in the practice, but one night, during sitting, I understood it for the first time. I realized that the various ambitions in which I was trapped—writing about zazen, writing about the brain that produced the writing, writing about the impossibility of what I was trying to do, and so on—were not just self-defeating but self-absorbed. They weren’t serving my zazen, and they weren’t serving my work. In fact, my work had become the antithesis of zazen, and this contradiction was sabotaging my zazen as well. How could I forget my self when I was obsessed with the brain that generated it? The more I fixated on my neurology, the more it reinforced the self that fixated on it. That was the real brain damage—self-absorption and the fixations it engendered. If I really wanted to understand the brain and brain damage, I needed to break through my self-absorption, let go of myself, look at others’ brains, others’ pain and pathology. It wasn’t fiction I needed to write. It was journalism. I needed to get out of my office, let go of myself, and meet real victims of actual brain damage face-to-face.

To study Zen is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self.

I’d done enough time in journalism to know how to seek out opportunities and permissions for research, but like any reporter, I found hospitals difficult to penetrate. After several rejections, I wrangled the permission of authorities at a VA hospital to spend time with a patient who was more or less a fixture on the ward. I owed my access to the fact that no one else wanted to be with him. He was dull and incurable, required almost no care, and had not excited researchers or even the students and interns who met him on rounds. They called him “the professor.” This was not a pseudonym but a link to his past life. Until viral encephalitis infected his brain three years before, he’d been chairman of the psychology department at a prestigious midwestern university, a respected teacher who’d published widely in his field.

He was a stocky man of medium height who walked the wards and grounds enough to keep himself in fairly good condition. His hair was gray and thin, but he looked younger than his sixty-two years. His dark eyes were fixed—no surprise—in a state of sad disbelief, but his face retained just enough of his past authority and intelligence to make it possible, though certainly not easy, to forget his condition. He was an unusual patient because, even though he’d lost his short-term and most of his long-term memory, he retained his verbal and motor function. He spent most of his time trying in vain to recover biographical information. Despite the fact that his wife and daughter and several former students visited him once or twice a month, he struggled to recall whether he was married, had children, had ever held a job, and, most obsessively, why he could not remember things. Again and again, as if with revelation, he said, “I think I have problems with my memory.” This discovery usually led to a long silence and, frequently, to the conclusion that his problem was caused by acid indigestion, which in turn was eased by candy bars. After I understood this and began to bring a stash when I visited, he was always glad to see me, but he never recognized me. If I left his room for even two or three minutes, he’d greet me when I returned as if he’d never seen me before. He liked to cover his deficit with one of two long-out-of-date expressions—“See you later, alligator!” or “After a while, crocodile!”—which, despite his amnesia, he retained from his adolescence.

The hospital was almost two hours away by train. Gray and cheerless, a void of a place, its architecture and atmosphere were not all that different from a prison. As I made the trip that first day, I thought a lot about a writer I’d recently been reading and rereading—Norman Mailer. I needed guidance and encouragement to make the leap from fiction to journalism—surrendering my subjective obsession with my own brain to an objective inquiry into the brain itself—and Mailer was my perfect muse. He’d made his name as a fiction writer with The Naked and the Dead, met critical disappointment with his next two novels, and then written a masterpiece of personal journalism, Armies of the Night. That book had required him to leave the privacy and solitude of his office to participate in an event of major historical and political proportions, the October 1967 March on the Pentagon. Though written in the third person, its hero was a perfectly realized character named Norman Mailer, who was ingeniously distinct from the author who’d created him. It seemed to me that Mailer had found his voice by letting go of himself, discovered his vision with total surrender to objective reality. The book he’d produced was a perfect combination of real-world description and novelistic skill. How could I ask for a better example as I set out to explore a world of medical catastrophe, which would surely humiliate my presumptuous attempts to imagine it?

The professor’s obsession was solitaire. Arriving with my bag of candy, I almost always found him in the midst of a game. He played hour after hour, all day long, every day, with fixed concentration that was clearly immune to repetition and boredom. Like each candy bar he was offered, each breakfast of each day when he awakened, every game was his first. Since this was before the days of the personal computer, he played with real cards, spreading them carefully on his tray table, which he rolled back and forth between his bed and the orange lounge chair in the corner of his room. As he spread his cards, his vacant eyes came alive with concentration, and the dark sadness of his face gave way to resolve and determination. His disease was a catastrophe he’d never escape, but inside the game, he was free of it.

Nothing settled my mind like watching him play. It seemed to me that, when he placed one card on another, he escaped his brain, arranged his life once and for all, liberated himself from anxiety.

Devoid of the instrument stands, rolling carts, and beeping alarms that turn most hospitals into auditory nightmares, the neurology ward was silent, almost serene. Three days a week for three weeks, I arrived midmorning with my notebook and a bag of candy and, for two or three hours, sat near the foot of his bed while he played. Thoughts of my book embarrassed me. Both the condition I was looking at and the effects of play on it made my attempt to understand the brain look shallow and insignificant.

Since there was no conversation between us, our routine became a ritual, a period in which I sat in something very like zazen. Nothing settled my mind like watching him play. It seemed to me that, when he placed one card on another, he escaped his brain, arranged his life once and for all, liberated himself from anxiety. Was that what I was doing when I followed my breath, straightened my back, and tried to forget myself? Was zazen after all a kind of solitaire without cards?

After a while there seemed to be no difference between us, no time but the present. I was detached and professional with him, but it seemed to me that our intimacy deepened every day. I can’t doubt that it was this feeling of intimacy that led me to cross the line between us.

He did not greet me when I arrived that morning. He was well into his game when I pulled my chair close to his bed. He nodded but did not veer from his cards. He lost that game and the one after that. By the time he was into his third, I had settled into the mind I’d come to expect in his room. I felt as if there were no time but the moment we shared, no difference between his state of mind and my own.

I could see by the speed with which he moved his cards that his third game was going well. Snap, snap—the cards came off the deck and found their way quickly to others. As if for the first time, I marveled at the fact that within the game he found an order and peace he could not attain without it. What did this say about the brain? What had I missed with all my obsessive thoughts about it? Were thoughts themselves like cards one tried to arrange?

Within a few moments, all his cards were consolidated in four neat piles near the top edge of his table. As often, the satisfaction on his face was so infectious that I felt it myself.

He paused for a moment to contemplate his success and then quickly collected his cards and arranged them in a deck. Finally, he reached for the bag of candy I’d brought. With no less interest than he’d shown in his cards, he examined its contents and extracted, unwrapped, and bit into a single bar with enthusiasm.

“You won,” I said.

“Yes!” he said.

“That’s great.”

“Yes!” he said.

“How are you today?”

He considered my question for a moment, then shook his head. “Not good. Not good at all.”

Abrupt mood shifts were hardly uncommon for him, but I’d never seen his face go dark more quickly. “I’m having problems,” he said, “with my memory.”

“Really? I’m sorry to hear that.”

“Am I married? Do I have children? I’m trying to remember...but I can’t!”

Until now, I’d always felt protective of him when he sank like this, trying my best to feel the frustration and desperation he felt. I knew it wouldn’t help, but I tried to offer him good thoughts—reminding him of his wife’s and daughter’s visits, the nurses and doctors who were always available to him, and so on. Just now, however, for reasons I’ll never understand, I felt no such urge. It was as if the intimacy we shared made me forget he was a patient and think of him as a friend. In fact, I felt just a little impatient with him.

“Why not forget?” I said.

“What?”

“You spend so much time trying to remember things—why not try to forget them? After all, you’ve got amnesia. You should be able to do that easily.”

“Amnesia?”

“Yes. You forget everything, right? What’s the big deal if you can’t remember your wife’s name? Forget everything and you won’t have to worry about it anymore.”

He stared at me for five or ten seconds in wide-eyed disbelief. Then he laughed aloud in three bursts separated by five or six seconds. He wasn’t smiling. One could not suspect that he found anything funny. Mirthless, hollow, louder and louder, like stage laughter by a bad actor or the “Ho! Ho! Ho!” of a professional Santa Claus, the sounds he produced seemed almost disconnected from him. He’d always been mild, congenial, no threat to anyone, but his face was angry and the laugh aggressive. I left the room quickly, but even at the far end of the long hall between his room and the nurses’ station, I heard him bellowing: “Ho! Ho! Ho! Ho! Ho! Ho!” The sound was one I’d never forget, and the fact that I left his room so quickly—literally ran away from him—was an act for which I’d never forgive myself.

Share

Related Books