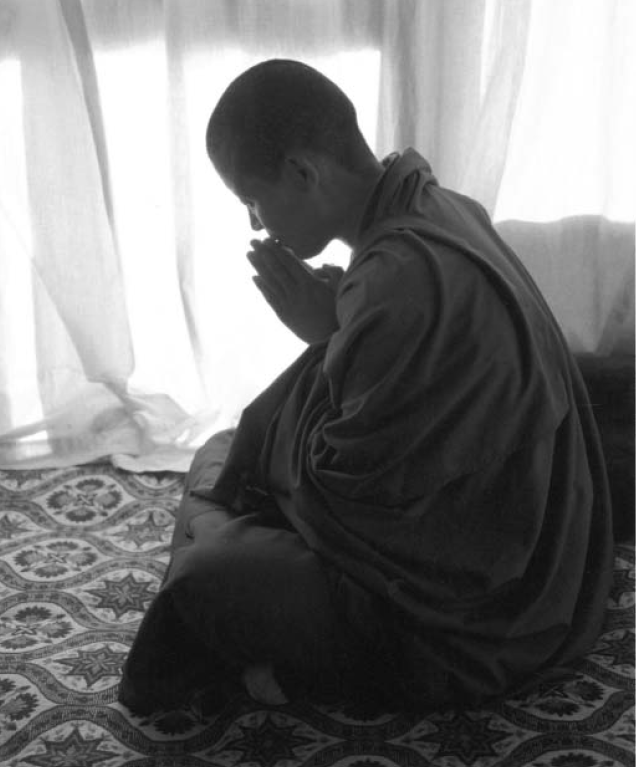

Anam Thubten: There are many ways to understand prayer. It means something different from person to person—and even for the same person, it might be different at different times.

To me, prayer is an act of devotion, and a non-conceptual, powerful method of dropping the ego mind of control, fear, doubt, and anger—right in the moment—and realizing the Buddhamind or bodhicitta. It is an act of surrendering everything to that great work of the universe—beyond anyone’s control—and trusting in the grand play of the universe. When you trust in it, you feel released from the fear and insecurity and accept—not acceptance like we are trying painfully to accept something we don’t appreciate, but true acceptance with trust.

The object of prayer is not so important in Buddhism, even though there are lots of deities and benevolent spirits. Buddhism teaches that deities such as Avalokiteshvara or Tara are not outside of oneself—they are an expression of one’s true nature, the emptiness, the source of all things, the absolute truth.

JC: So praying to Chenrezig is a way of calling on your own inner strength to help make circumstances go in a better way?

AT: Absolutely. In the Tibetan tradition, we have these three buddhas (or bodhisattvas), Manjushri, Avalokitesvara, and Vajrapani. Manjushri symbolizes intelligence and wisdom, Avalokiteshvara symbolizes love and compassion, and Vajrapani symbolizes strength, courage and power. They are all expressions of what we truly are; each of these principles is an inherent property of our basic nature. So when we pray to them, it is an act of invoking those inherent enlightened qualities present in all of us. In the ultimate sense, there is no object that is being prayed to—there is no separation between the object being prayed to and the person praying.

JC: In your book No Self, No Problem you discuss how acceptance is a key to waking up to your true nature. Does this mean that one should go along with whatever is happening?

AT: Part of Mahayana teaching is about bringing all things onto the path to enlightenment. This means that whatever happens, you accept it as a way to develop the enlightened qualities inside you—courage, love, forgiveness, compassion. From another perspective, the concept of acceptance is tricky because it has a connotation that you have to deliberately try to convince yourself to accept everything. The big question is who is it that is trying to accept and reject in the first place—the ego is present as the one trying to accept. The ego is running this whole game.

JC: So the acceptance you are speaking of is not the opposite of rejection?

AT: No, it is not the opposite. The enlightened mind (Rigpa or Buddhamind) goes beyond both accepting and rejecting—there is nothing to accept or reject—because Buddhamind is in perfect relation with the nature of all things. In this realm there is no conflict. So the idea of accepting and rejecting is really transcended. It doesn’t exist there; it only exists in the ego’s mind. In the Dzogchen tradition, the notion of accepting is regarded as a subtle effort of ego that has to be dropped in order realize the great peace or nature of all things.

JC: In your book, you use the term “non-doing awareness.” Can a person maintain non-doing awareness even while action is going on?

AT: Absolutely. Non-doing awareness is not about whether you are doing some thing or not. The art of maintaining non-doing awareness is a rich practice.

JC: Is the opposite of non-doing awareness the thinking of oneself as the doer?

AT: The non-doing awareness can have different meanings. On one level we can speak of awareness as not doing anything. Awareness transcends all notions of effort. It doesn’t try to reject or acquire. It is already enlightened, so there is nothing to purify, nothing to abandon, nothing to achieve. It itself is non-doing, it doesn’t involve any effort or strategies in itself.

JC: It is aware of the content of experience.

AT: Absolutely. When one resides in that, it is totally different from any ordinary state of mind. It is different from trance states or samadhi which many people regard as spiritual. When one experiences pure awareness, there is no doing because there is nothing to be done. There is no act of trying to purify. There is nothing to acquire. It is in perfect harmony and relation with ultimate truth. The ordinary mind is very engaged in some kind of effort to dismantle the empire of the ego delusion and in trying to acquire something. It is very involved with doing.

JC: Awareness is present in all states but we don’t notice it.

AT: Exactly. It is insight, knowing the nature of all things, the profound absolute truth of all things. In Tibetan, awareness is called Rigpa or Yeshe. “Ye” means primordial—it is already in each of us—that innate wisdom is not some conception or knowledge that we can acquire from reading, thinking or lectures. It is inherent in each of us. “She” means knowing the inconceivable, transcendent, and yet simple truth of all things. We can call it emptiness, dharmata. The rational mind cannot comprehend it. Awareness in this sense is insight (prajna). It is not that we are just enjoying some kind of stillness or some beautiful state of mind. Whenever we can reside in this—this is the highest form of practice—in that moment our mind is no longer different than the mind of Buddha Shakyamuni.

JC: Does this awareness have the three qualities of the three buddhas you spoke of earlier?

AT: Absolutely. This awareness doesn’t happen with a big procession. It happens in a quiet and subtle manner. It is unfathomable like the ocean whose depth we cannot see. Awareness is the Buddhamind, a reservoir of enlightened radiance of wisdom, joy, compassion, love—they just happen on their own. Like the brilliant sun in the sky, it is the source of all the enlightened qualities that radiate from it. They are innate and are an expression of that awareness.

JC: So for someone with this awareness the qualities of intelligence, love, and compassion naturally radiate into their environment and spontaneously change things.

AT: Yes. There are stories of the Buddha traveling into towns and cities; he brought his amazing benevolent presence. When someone is fully immersed in this awareness, what he or she naturally does is express that enlightened nature. There was a lama named Mani Lama from Golok. When he was a young boy, he had a sudden awakening. He left his ordinary life, and traveled around eastern Tibet. Because he was not educated in a monastery, he didn’t know how to teach in a traditional way, but people felt a tremendous peace around him. So wherever he went, people would gather around him. Because he didn’t know what to teach, his teachings were short. People would come and sit with him. Sometimes he gave spontaneous talks or would sing with them. Often he would sing the Mani or six-syllable mantra, and so people called him the Mani Lama. This is a great example of how, when someone lives in awareness, then his or her being becomes a radiance of compassion and love.

JC: Since awareness is present in each of us, what does it mean to practice being aware?

AT: Awareness is the nature of our mind and is not deceived by the world of illusion or display. When mind is deceived, we are deluded, ignorant of our true nature; this is the foundation of samsara, of conflict and suffering. The other side is the awareness or enlightened mind which sounds very grand but is very simple. Each moment is a tipping point—each moment we decide whether or not to be enlightened and free! There is a verse in one of the spiritual songs: “There is only one ground (the dharmadhatu or source or underlying truth of all things), only two paths and only two fruitions.” This is one of my favorite verses, because it says there are not three paths, only two paths, the path of awareness and the path of unawareness. Every moment we either choose to be on the path of awareness or on the path of non-awareness. So in each moment we are enlightened or not. When we really contemplate this verse, it shocks our minds. It is easy for many practitioners to think that even though they are not actually residing in awareness that somehow so long as they are doing the various practices they are making some kind of progress according to some invisible scale or record—because they are doing all the right practices they are going in the right direction. When you contemplate this teaching, it shocks your mind because you realize you are making the enlightenment choice in every moment.

Basically two things are happening, everything else is irrelevant—either you are enlightened in this moment or not. It is possible that I could be sitting on a beautiful meditation seat and doing all sorts of spiritual practices but I am completely unawakened. On the other hand, I might be cleaning my toilet and wearing blue jeans, but I could be residing in the awareness—this is what matters.

In the end, there is only one practice, that of maintaining awareness. And because it is uncontrived, it is not the effect of a cause—you cannot produce awareness. Whatever you can produce is “nyam,” an altered state of consciousness—it can be enticing, seductive, whatever. People can get lost in nyams and think this is rigpa, bodhicitta, or samadhi. But mind is deceiving itself. Awareness cannot be produced. Buddha was asked “What causes mindfulness?” and he said, “Mindfulness itself.” This answer is perfect—and can be non-satisfying.

There is a lama from Kham who said that the only way that you can have genuine realization is by holding 108 sessions a day. What he means is not that we must have literally 108 sessions a day but rather that we should remember periodically throughout the day to pause. Pause and stop talking, wherever you are, as a way to get back to awareness.

JC: Getting lost in thought seems to me to be a big obstacle to being aware.

AT: Buddha spoke of attention as one of the most powerful methods to become free. Instead of going along with the mind and believing its stories—living the dream-like life—Buddha was suggesting to pause, to stop and look deeply into the nature of all things. Instead of wandering and dreaming, pause and look carefully and pay attention to everything carefully. When we do that, sometimes the perfect understanding or prajna reveals itself to us—we have the direct insight into all things, simply by paying attention to the depth of all things. We stop and pause as a way of questioning what the truth is, what freedom is.

This is an effective method for waking up. Right now in this moment. When we practice the traditional Buddhist methods we talk about mindfulness, we talk about paying attention to the breath and one’s activities. The true meaning of paying attention is more than about paying attention to the body or breath—it is a way of stopping the work of the deluded mind, stopping the wheel of suffering that the ego is spinning. Look into the depth with a sharp, keen observation so that we can see the truth right there. You will stop spinning the wheel of delusion and see that the truth of all things or emptiness is not so far from us—it is everywhere.

JC: It is empowering, and humbling, to think that each moment we make a choice to be awake or not.

AT: In that sense it is very simple but it requires a lot of dedication and discipline to break down all the habits that distract us from awareness. It takes lots of meditation practice.

JC: Thank you Rinpoche for this teaching—I really appreciate your time for this.