| The following article is from the Summer, 1992 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

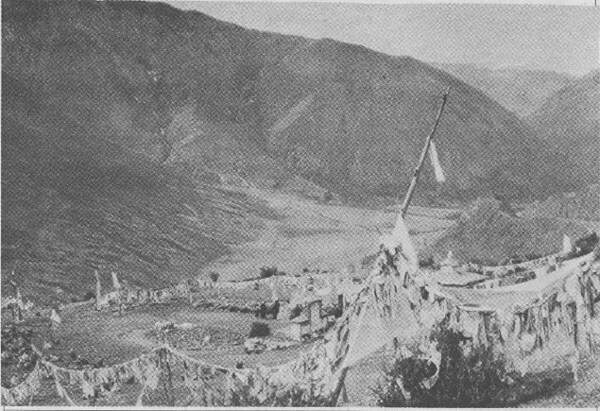

High above Drigung Monastery, the trail levels off onto a meadow where several small chortens, hundreds of snapping prayer flags, and a twelve-meter circle of flat, black stones marks the Drigung dundro, one of Tibet's most ancient and sacred sky burial sites. We walked slowly through a sea of giant vultures that danced and hissed in anticipation of another human's last act of generosity on this earth. Juniper branches smoldered in a stone incense furnace nearby, purifying the high-altitude air with the sweet aroma. Stretched across a large, flat, knee-high boulder at the edge of the circle of stones lay the four-day-old corpse of a young Tibetan being cut by two rogyapa (Tibetan funeral butchers) into pieces small enough for the vultures and crows to ingest. The day was clear and, from the dundro's vantage point, one might well have been able to see into the next life.

An invitation from a lama at Drigung Monastery had made this visit possible. He had not only remembered our previous visit in 1988 as the Cultural Arts Expedition, but had learned from our interpreter about our recent book, White Lotus, and our hosting of the Dalai Lama at the University of Findlay only two months before. We knew this invitation would afford a once-in-a-lifetime experience, since it is a Tibetan ceremony that is strictly forbidden to onlookers.

The evening before the sky burial, a prayer service had been conducted in the dusty courtyard of Drigung Monastery by the lama and fifteen monks. This may have been the final mystical chant of the De-wa-chan-kyi-mon-lam service which directs the deceased's spirit on the right path to reach Amitabha's Western Paradise. Seated in an upright, embryonic posture in the center of the monastery grounds, the corpse was wrapped in a robe, except for the top of its head, which was exposed to the air. The only sound in the courtyard was the low droning of the chanting from the monks who encircled the corpse.

This was the end of the four-day period between the time of death and the sky burial, when the deceased's spirit would complete its transition from the physical into the spiritual realm. For me, as an artist, it was a time for conceptualizing and visualizing, for these are the experiences from which art is born.

According to an ancient Tibetan legend, the Drigung dundro is ethereally connected to the famous Sitavana burial site in India, both protected by the guardian deity Tibkyi Chang. Tibetans have transported their deceased to Drigung from both the eastern and western regions of Tibet since the eleventh century. Besides being the deceased's final act of generosity to the living, the sky burial, which may have been adapted from an ancient Parsee custom, is a practical form of disposal, because Central Tibet's rocky terrain prohibits digging graves, and wood fuel for cremation is not abundant.

My two traveling companions and I sat on a boulder, intensely watching the thogthen (ritual master) mark a mandala on the chest and stomach of the corpse. With large machetes the rogyapa sliced the flesh across the trunk according to the thogthen's directions, after which they unceremoniously removed the organs and began cutting the tissue from the bone. The bones were beaten with crude but practical stone mallets and were mixed with barley flour before being thrown onto the black stone Demchok mandala, where impatient birds consumed the bits of flesh. Three men paced around the circle's perimeter, swinging four-foot sections of doubled rope, which kept the vultures at bay until enough meat had been thrown into the center to feed a large number of birds. The creatures charged onto the stones with ravenous excitement, jumping and hissing violently and intimidating one another with their six-foot wing-spreads.

I, too, was intimidated by the huge birds, but not so much that I was unwilling to become part of the experience. I was not totally aware of the dundro's impressive and ancient history, and the risk I was taking. Without contemplating the possible consequences, I walked over to the Tibetan nearest me and gently took the rope out of his hands. He resisted for a moment, but then let me take it. Both of us were surprised and I realized that this might be the first time a Westerner had been allowed to be more than a spectator at this ceremony. In those few seconds the vultures had moved in close to the stone circle, their eyes fixed on what little had been thrown there. I began pacing back and forth along the outside edge of the stones, slowly swinging the rope like a giant propeller, slapping the dusty ground only inches from the large creatures. About every twenty minutes the rogyapa signaled us to allow the birds to charge onto the stones, at which time the vultures seemed to inhale anything that was not rock.

While I did this I worked my way around the large flat stone where the rogyapa continued the cutting process. I moved in very close, chasing away any birds that came too near to the uncut corpse. For a moment, one of the rogyapa, wielding a rough-edged, blood-stained machete, glanced in protest at my being near the ritual. At the same moment, the second rogyapa swung a large stone mallet down onto a protruding leg bone, sending tissue, and what seemed to be blood, flying onto my pants, sweater, and face. His knife-bearing partner was delighted; perhaps he felt that I had thereby received the prerequisite initiation. With a half-smile that bordered on gleeful satisfaction, he continued to chop small chunks of flesh from the thigh. By that time I had become so caught up in the ritual that I was not in the least repulsed by the process nor the corpse which had been reduced to unidentifiable parts. I stayed close to the rogyapa, swinging the rope and watching closely as they cut up the last sections of muscle and tissue.

Vultures at Drigung Dundro Photo: Carole Elchert

While the vultures ingested what seemed to be the final course in their repast, the thogthen who had marked the mandala on the corpse several hours earlier came out of a small stone hut next to the chorten, clutching the half-cleaned skull of the young man whose body had, by then, completely disappeared. Over the rock bloodied by the cutting and hammering, the ritual master held the skull out and chanted a prayer that directed the spirit to leave the body and physical world. I stood next to the thogthen as he and the two rogyapa scratched a four-inch steel needle along the jagged crack, referred to as the Aperture of Brahma, on the crown of the skull. The three of them closely examined several small marks on the skull bone, trying to determine if the spirit had escaped. Finally, the thogthen pushed the sharp steel needle deeply into the crack and completely through the skull bone, assuring the spirit a door of departure. I assumed that since this particular young man had died a violent death, the thogthen wanted to be sure that the spirit, which was probably confused and disoriented in its fourth day of the bardo (after-death state), was given every possible opportunity to find its way out of the body.

Drigung Dundro Photo: Carole Elchert

By then, the vultures had begun to wander off the stone mandala, pruning their wing feathers, unaware of what was to come. The ritual master set the skull on the cutting rock where a rogyapa struck it once with a forceful blow from the heavy stone mallet. The skull was split wide open and the exposed brain was quickly scooped out and thrown onto the stones. The rogyapa beat the skull bone into small pieces and mixed the fragments with the barley flour, all of which was eaten by the vultures in a matter of seconds. What bone or tissue was left by the vultures was found and consumed by dogs or the govo (eagles). These large birds carry the bone high in flight, dropping and breaking the bone into smaller, digestible pieces.

A few minutes later, a Tibetan brought a bucket of cold water out of a hut where the rogyapa had already begun to wash themselves. The rogyapa were wearing aprons, but their feces, hands, and arms were stained dark red. The rogyapa who had earlier opposed my help rushed at me with his bloody hands to wipe them across my rag-wool sweater, which I was painstakingly rubbing with a wet rag to clean. He broke into laughter when I jumped back from his antics and exclaimed meh, meh in Tibetan. The rogyapa's dispositions changed immediately after they had cleaned themselvesfrom a serious state of propriety to a relaxed mood. The typical Tibetan sense of humor transported everyone back to the world of the living.

The sky burial is an extremely serious and sobering affair, not only for the family and the spirit undergoing transformation, but for everyone witnessing the process. One wrong move by an out-sider who views the ceremony without understanding, respect, or permission may cast a bad omen over the entire event.

An adventurous friend of ours who lived in Nepal for many years once tried to view a sky burial near Sera Monastery in 1985. Even though he spoke some Tibetan, he was chased by an angry macheteswinging rogyapa and had to fight his way loose from the rogyapa's grip and the threatening blade of the knife. He walked back to Lhasa covered with the blood from the rogyapa's wet hands and apron. Once a Tibetan advised me, Never show up at a sky burial unannounced, or you may discover it to be your own''. This advice is a good foundation on which to develop a healthy respect for a Tibetan ceremony that guarantees, if completed according to its strict guidelines, an open pathway towards liberation.