Guo Gu

Guo Gu (Dr. Jimmy Yu) is the founder of the Tallahassee Chan Center (www.tallahasseechan.com) and is also the guiding teacher for the Western Dharma Teachers Training course at the Chan Meditation Center in New York and the Dharma Drum Lineage. He is one of the late Master Sheng Yen’s (1930–2009) senior and closest disciples, and assisted him in leading intensive retreats throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia. Guo Gu has edited and translated a number of Master Sheng Yen’s books from Chinese to English. He is also a professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Florida State University, Tallahassee.

-

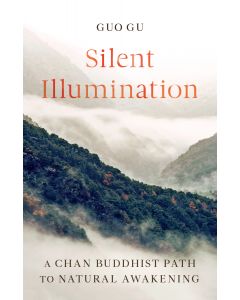

Silent Illumination$16.95- Paperback

Silent Illumination$16.95- Paperback -

The Essence of Chan$16.95- Paperback

The Essence of Chan$16.95- Paperback -

Passing Through the Gateless Barrier$34.95- Paperback

Passing Through the Gateless Barrier$34.95- Paperback