Charles B. Jones

Charles B. Jones is an associate professor of Religious Studies at The Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. He earned a PhD at the University of Virginia in 1996 and specializes in Pure Land Buddhism in China.

Charles B. Jones

GUIDES

Zen in Japan: Up to the Meiji Restoration

This is part of a series of articles on the arc of Zen thought, practice, and history, as presented in The Circle of the Way: A Concise History of Zen from the Buddha to the Modern World. You can start at the beginning of this series or simply explore from here.

Explore Zen Buddhism: A Reader's Guide to the Great Works

Overview

Chan in China

- The Works of the Chan and Zen Patriarchs

- The Works of Zen in the Tang Dynasty (618-907)

- The Works of Zen in the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279)

- The Great Koan Collections

Zen in Korea

Zen in Japan

- Early Zen in Japan

- Dogen: A Guide to His Works

- Rinzai Zen

- Hakuin Ekaku: A Reader's Guide

- The Samurai and Zen

> Zen in Japan up to the Meiji Restoration

Additional Resources

- The Heart Sutra: A Reader’s Guide

- Zen in the Modern World (Coming Soon)

- Foundational Sutras and Texts of Zen (Coming Soon)

- Zen and Tea

The period after Dogen and the early period of Zen saw rich developments, including of course the Rinzai school and the Samurai which are covered in the sister guides to this article. Here are some of the works we publish from after the early period up to the 19th century Meiji Restoration when changes in power made for a more challenging environment for Zen practitioners and institutions throughout Japan.

Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record: Zen Comments by Hakuin and Tenkei

Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record is a fresh translation featuring newly translated commentary from Hakuin of the Rinzai sect of Zen and Tenkei Denson (1648–1735) of the Soto sect of Zen.

Ryokan

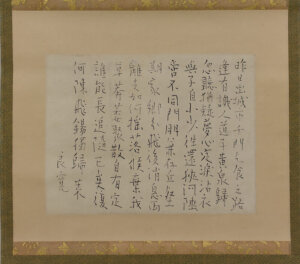

Chinese Poem Lamenting the Death of a Friend by Ryokan from the Met

Ryokan (1758–1831) is, along with Dogen and Hakuin, one of the three giants of Zen in Japan. But unlike his two renowned colleagues, Ryokan was a societal dropout, living mostly as a hermit and a beggar. He was never head of a monastery or temple. He liked playing with children. He had no dharma heir. Even so, people recognized the depth of his realization, and he was sought out by people of all walks of life for the teaching to be experienced in just being around him. His poetry and art were wildly popular even in his lifetime. He is now regarded as one of the greatest poets of the Edo Period, along with Basho, Buson, and Issa.

Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan

He was also a master artist-calligrapher with a very distinctive style, due mostly to his unique and irrepressible spirit, but also because he was so poor he didn’t usually have materials: his distinctive thin line was due to the fact that he often used twigs rather than the brushes he couldn’t afford. He was said to practice his brushwork with his fingers in the air when he didn’t have any paper. There are hilarious stories about how people tried to trick him into doing art for them, and about how he frustrated their attempts. As an old man, he fell in love with a young Zen nun who also became his student. His affection for her colors the mature poems of his late period. This collection contains more than 140 of Ryokan’s poems, with selections of his art, and of the very funny anecdotes about him.

Dewdrops on a Lotus Leaf: Zen Poems of Ryokan

Deceptively simple, Ryokan's poems transcend artifice, presenting spontaneous expressions of pure Zen spirit. Like his contemporary Thoreau, Ryokan celebrates nature and the natural life, but his poems touch the whole range of human experience: joy and sadness, pleasure and pain, enlightenment and illusion, love and loneliness. This collection of translations reflects the full spectrum of Ryokan's spiritual and poetic vision, including Japanese haiku, longer folk songs, and Chinese-style verse. Fifteen ink paintings by Koshi no Sengai (1895–1958) complement these translations and beautifully depict the spirit of this famous poet.

One Robe, One Bowl: The Zen Poetry of Ryokan

The hermit-monk Ryokan, long beloved in Japan both for his poetry and for his character, belongs in the tradition of the great Zen eccentrics of China and Japan. His reclusive life and celebration of nature and the natural life also bring to mind his younger American contemporary, Thoreau. Ryokan's poetry is that of the mature Zen master, its deceptive simplicity revealing an art that surpasses artifice.

Ikkyu

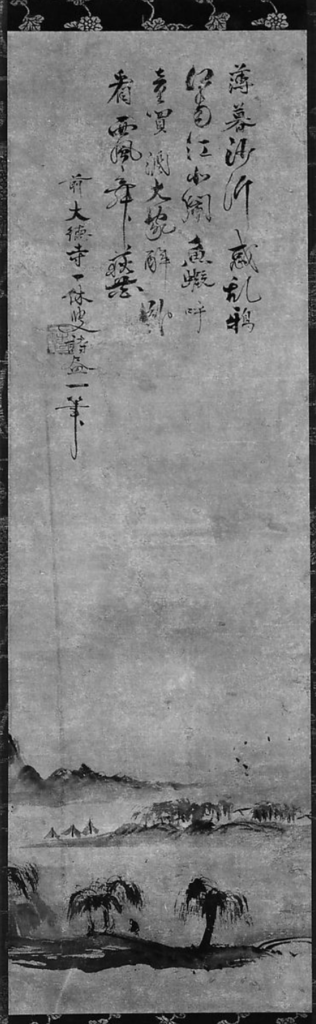

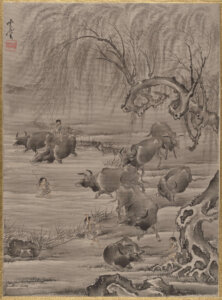

Twilight Landscape

In the Style of Ikkyū Sōjun Japanese. From the Met.

Finally, there is the figure of Ikkyu (1394–1481). While we do not have any stand-alone works on or by him, he appears in many, many works. In The Circle of the Way, he gets a few pages that begins:

Of all Muromachi-period Zen monastics, with all of their talent and accomplishments, the monk most well known today was something of a black sheep. Ikkyu Sojun (1394–1481) remains so popular in Japan that he has been portrayed in anime and the popular graphic art of manga.

Peter Matthiessen, In Nine-Headed Dragon River: Zen Journals, adds more color with his flowing prose, describing him as

A bastard son of the emperor, pauper, poet, twice-failed suicide, and Zen master, enlightened at last by the harsh call of a crow. At eighty-one Ikkyu became the iconoclastic abbot of Daitoku-ji. ('For fifty years I was a man wearing straw raincoat and umbrella-hat; I feel grief and shame now at this purple robe.') His 'mad' behavior was perhaps his way of disrupting the corrupt and feeble Zen he saw around him: 'An insane man of mad temper raises a mad air,' he wrote. He also said, 'Having no destination, I am never lost.' One infatuated scholar has called him 'the most remarkable monk in the history of Japanese Buddhism, the only Japanese comparable to the great Chinese Zen masters, for example, Joshu, Rinzai, and Unmon.' Ikkyu found no one he could approve as his Dharma successor. Before his death, civil disorders caused the near obliteration of Kyoto, forcing Rinzai Zen to follow Soto from the decadent capital city into the countryside.

by Jim Harrison

A collection of poems inspired by Ikkyu by the great novelist and essayist Jim Harrison who said of this work,

The sequence After Ikkyu- was occasioned when Jack Turner passed along to me The Record of Tungshan and the new Master Yunmen, edited by Urs App. It was a dark period, and I spent a great deal of time with the books. They rattled me loose from the oppressive, poleaxed state of distraction we count as worldly success. But then we are not fueled by piths and gists but by practice—which is Yunmen’s unshakable point, among a thousand other harrowing ones. I was born a baby, what are these hundred suits of clothes I’m wearing?

Naked in the Zendo: Stories of Uptight Zen, Wild-Ass Zen, and Enlightenment Wherever You Are

While not by Ikkyu, he makes an appearance in this work over a few very entertaining and moving pages.

Zen in the Age of Anxiety: Wisdom for Navigating Our Modern Lives

Ikkyu makes an appearance for several pages of Tim Burkett's excellent work which includes translations, by John Stevens, of several of his poems

You Have to Say Something: Manifesting Zen Insight

Dainin Katagiri Roshi shares this story about Ikkyu in this work:

A man who was soon going to die wanted to see Zen master Ikkyu. He asked Ikkyu, ‘‘Am I going to die?’’ Instead of giving the usual words of comfort, Ikkyu said, ‘‘Your end is near. I am going to die, too. Others are going to die.’’ Ikkyu was saying that we can all share this suffering. Persons who are about to

die can share their suffering with us, and we can share our suffering with those who are about to die.Ikkyu’s statement comes from a deep understanding of human suffering. In facing your last moment, you can really share your life and your death.

Minding Mind: A Course in Basic Meditation

One of the meditation manuals in this work date from pre-Meiji Restoration Japan.

The second, An Elementary Talk on Zen, is attributed to Man-an, an old adept of a Soto school of Zen who is believed to have lived in the early seventeenth century. The Soto schools of Zen in that time traced their spiritual lineages back to Dogen and Ejo , but their doctrines and methods were not quite the same as the ancient masters’, reflecting later accretions from other schools.

Man-an’s work is very accessible and extremely interesting for the range of its content. In particular, it reflects a modern trend toward emphasis on meditation in action, which can be seen in China particularly from the eleventh century, in Korea from the twelfth century, and in Japan from the fourteenth century.

Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice

This recent work by Professor Charles B. Jones, a leading scholar on Pure Land Buddhism, goes into much detail of Pure Land and its intertined relationship with Zen. The sections on Japan include its introduction from China, Ryonin and the Yuzi Nenbutsu, Honen and Jodo Shu, Shinran and the Jodo Shinshu, and Ippen and the Jishu.

Continue to our next article in the series: A Readers Guide to the Heart Sutra >

The White Lotus Society

It is very difficult to identify a precise moment when Buddhism first entered China. Stories and legends abound, and it is unlikely we will ever know the truth of the matter. The most we can say is that it occurred somewhere around the turn of the first millennium in the middle years of the Han dynasty, and the religion arrived with merchants and traders coming into China from the Silk Road in the northwest and in commercial ports along the southeastern seaboard. It probably subsisted for a time among communities of foreign visitors and immigrants from central Asia and for a time remained below the average Chinese citizen’s threshold of awareness.

Before a Pure Land tradition (or indeed any form of Chinese Buddhism) could develop, the Chinese people had to learn of it, develop an interest in it, and acquire materials in their own language. Translation activity was sporadic and haphazard. Chinese is not related in any way to the Indic family of languages, and often such basic tasks as naming native Indian plants or rendering personal names proved daunting. Early translators worked without any established standards, and they translated texts that interested them or their audiences personally in whatever way they could improvise. The results were (and still are) difficult to read, ungrammatical, and often used Chinese characters for their sound-value to represent the pronunciation of Indic words. When a translator used a native term that appeared equivalent, it often had preexisting connotations and associations in Chinese that could throw the reader off.

For any new religious trend to launch, people need to come together around the texts and institute practices based upon them.

Nevertheless, translations appeared, and immigrant monks helped the early adopters to work through the texts and decipher their meanings. Significantly, some of the earliest texts to circulate had some bearing on Pure Land ideas and practices. A translation of the Pratyutpanna Sūtra appeared in 179, making it one of the earliest texts to become available. In addition, the earliest translations of the Larger Sūtra, the very source of Amitābha’s story, may have begun circulating in this early period, though some scholars believe it may have become available a century or two later. However, the mere availability of scriptural texts was not enough to call a Pure Land movement into being. For any new religious trend to launch, people need to come together around the texts and institute practices based upon them. Accordingly, the Chinese Pure Land tradition itself traces its inception not to the appearance of translations, but to a meeting that took place in the year 402.

The “White Lotus Society” of Lushan Huiyuan

Once again, it is best to begin with a story, this time concerning Lushan Huiyuan (Huiyuan of Mount Lu, 334–416). During the turbulent centuries following the fall of the Han dynasty, kingdoms rose and fell in quick succession. In response to the prevailing insecurity, Huiyuan left his home in the north and settled on Mount Lu near the northern border of modern Jiangxi province. The setting, which looks like a spectacular Chinese landscape painting, gave him a refuge from the storms of war and politics. The site also attracted many eminent literati and former courtiers who likewise sought a haven beyond the reach of the tumult.

Well-known Buddhist authors designated Huiyuan the first “patriarch” (Ch.: zu) of Pure Land.

In the year 402, so the story goes, 123 of these laymen approached Huiyuan and asked him to officiate a ceremony for them. They wished to worship the buddha Amitābha and seek rebirth in “the western region.” Huiyuan consented and asked one of them to compose the ritual texts. He set up an image of Amitābha and led them in setting forth their aspiration to attain rebirth in the west after death. Subsequently, the Pure Land tradition in China referred to this group as the “White Lotus Society” and celebrated their gathering as the first appearance of Pure Land practice in China. About five hundred years later, well-known Buddhist authors designated Huiyuan the first “patriarch” (Ch.: zu) of Pure Land, and many organized societies of their own were modeled on his.

From a historical perspective, this honor rests on shaky foundations. As one examines the text of the White Lotus Society’s liturgy, one wonders how well the participating literati understood what they were doing. They refer to “the west” or “the western region,” but never name the Land of Utmost Bliss. They describe the land of Amitābha in terms more appropriate to a Daoist paradise than to the canonical land of Sukhāvatī. As for Huiyuan himself, he does not seem anything like a Pure Land practitioner. The literati living around Mount Lu took the initiative in organizing the ritual and composing the texts, while Huiyuan provided the facilities and officiated. His own practice of meditating on buddhas came primarily from the Pratyutpanna Sūtra mentioned above, and his goal was to gain a vision of the buddhas of the present as that scripture instructs, not rebirth in a buddha-land. On his deathbed, he took great care to keep the monastic rules until the very end and did not display any concern at all for rebirth in the Pure Land. His contemporaries did not think him an apt model for Pure Land practice.

Nevertheless, Huiyuan’s writings contained one memorable phrase that became a slogan for the later Pure Land tradition. In a preface he contributed to a collection of his disciples’ poems, he wrote that “the names of the various forms of samādhi are legion, but for height of merit and ease of practice the nianfo samādhi is foremost.” The phrase nianfo samādhi here refers to a deep meditative concentration in which one visualizes buddhas. Even though this does not refer to the practices that predominated in Pure Land later on, the phrase stuck as a way to “sell” the tradition and defend it from detractors.

If [Huiyuan] was not the ideal Pure Land devotee in life, he became one in later Pure Land literature.

The story of Huiyuan and his White Lotus Society still matters, however. Once the event turned into the definitive beginning of the tradition and Huiyuan gained recognition as its first patriarch, subsequent biographies refashioned his life story into one in which he was an ardent practitioner of Pure Land who had visions of Amitābha several times after he moved to Mount Lu. His death narrative was rewritten to say that a week prior to his death, Amitābha appeared to him to tell him to prepare for his rebirth, and he died peacefully with this buddha’s name on his lips. If he was not the ideal Pure Land devotee in life, he became one in later Pure Land literature.

Share