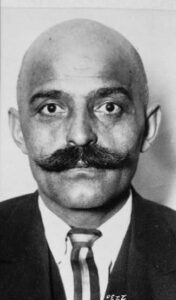

G. I. Gurdjieff

G. I. Gurdjieff (1866–1949) created an original system of self-transformation that reconciled the great mystical traditions, known as the "Fourth Way" or "the Work." He initially gathered pupils in Moscow and in 1915 organized a study group in St. Petersburg that included P. D. Ouspensky, a leading figure in the spread of the teachings. Amid revolutionary turmoil in Russia, in 1917 he moved to the Caucasus and in 1922 established an institute for his work in France. The sources of the present book stem from this early period.

G. I. Gurdjieff

GUIDES

An Excerpt from In Search of Being

If we wish for self-knowledge, we must strive for freedom.

Our picture of ourselves is formed by what we experience. Each of us comes into the world unsoiled, like a clean sheet of paper. Then people and circumstances around us begin vying with each other to sully this sheet, to cover it with writing. Education, the formation of morals, information called “knowledge”—all feelings of duty, honor, conscience and so on—enter here. And all these people claim that the methods adopted for grafting these shoots known as man’s “personality” to the trunk are immutable and infallible. Gradually the sheet is soiled, and the more covered with so-called “knowledge” it becomes, the cleverer we are considered to be. The more writing in the place called “duty,” the more honest we are said to be. So it is with everything. And we, seeing that people regard this soiled veneer as merit, consider it valuable. This is an example of what we call “man,” to which we often even add such words as “talent” and “genius.” Yet such a genius will have his mood spoiled for the whole day if he does not find his slippers by his bed when he wakes up in the morning.

We do not realize that we are not free either in our manifestations or in our life. None of us can be what we wish to be and what we think we are. None of us is like our picture of ourselves, and the words “man, the crown of creation” do not apply to us. “Man”—this is a proud term. But we must ask ourselves: what kind of man? Not the person, surely, who is irritated at trifles, who gives his attention to petty matters and is distracted by everything around him. To have the right to call oneself “man,” we must actually be man. And this “being” comes only through self-knowledge and development in directions that become clear through self-knowledge.

Let us each ask ourselves: are we free?

If we wish for self-knowledge, we must strive for freedom. The aim of self-knowledge and the possibility of self-development are of such importance and seriousness—they demand such intensity of effort— that to attempt this in any old way and among other interests is impossible. If we undertake this aim, we must put it first in our life, which is not so long that we can afford to squander it on trifles. In order to be able to spend our time profitably in our search, we need freedom from every kind of attachment. Freedom and seriousness. Not the kind of seriousness that looks out from under furrowed brows with pursed lips, carefully restrained gestures and words filtered through the teeth, but the kind of seriousness that means determination and persistence, intensity and constancy in the undertaking, so that, even when resting, we continue in the search. Let us each ask ourselves: are we free?

In order to see anything of this, we have to look objectively, from the outside.

If we are relatively secure in a material sense and do not have to worry about tomorrow, if we depend on no one for our livelihood or in the choice of our conditions of life, we are inclined to answer yes. But the freedom we need is not a question of external circumstances. It is a matter of our inner structure and our attitude toward these inner conditions. But perhaps we think that our incapacity is only true for our automatic associations, that with regard to things we “know” the situation is different.

In the course of our life we are learning all the time, and we call the results of this learning “knowledge.” Yet, despite this knowledge, we often prove to be ignorant, remote from real life and therefore ill-adapted to it. Most of us are half-educated, like tadpoles, or more often simply “educated” people with a little information about many things, all of it fuzzy and inadequate. Indeed, it is merely information. We cannot call it knowledge, because knowledge is an inalienable property of a person. It cannot be more, it cannot be less. For a person knows only when he himself is that knowledge. As for our convictions—have we never known them to change? Do they not also fluctuate like everything else in us? It would be more accurate to call them opinions rather than convictions, dependent as much on our mood as on our information, or perhaps simply on the state of our digestion at a given moment.

Every one of us is a rather ordinary example of an animated automaton. We may think that a “soul,” and even a “spirit,” is necessary to act and to live as we live. But perhaps it is enough to have a key for winding up the spring of our mechanism. Our daily portions of food help wind us up, and renew the aimless antics of our associations, again and again. From these, separate thoughts are selected. We attempt to connect them into a whole and pass them off as valuable, and as our own. We also pick from feelings and sensations, moods and experiences. And out of all this we create the mirage of an inner life.

In order to undertake this in a rational way, we have to see what needs to be cleaned, and where and how.

We call ourselves conscious and reasoning beings, talk about God, eternity, eternal life and other higher matters. We speak about everything imaginable, judge and discuss, define and evaluate. We omit, however, to speak about ourselves and about our own real, objective value. For we are all convinced that we can acquire anything that may be lacking in us.

As already said, there are people who hunger and thirst for truth. If we examine the problems of life and are sincere with ourselves, we become convinced that it is no longer acceptable to live as we have lived and to be what we have been until now. A way out of this situation is essential. Yet we can develop our potential capacities only after cleaning out the material that has clogged our machine over the course of our lives. In order to undertake this in a rational way, we have to see what needs to be cleaned, and where and how. And to see this for oneself is almost impossible. In order to see anything of this, we have to look objectively, from the outside. For this, mutual help is necessary.

This is the state of things in the realm of self-knowledge. In order to “do” we must know, but to know we must find out how to know. We cannot find this out by ourselves.

Share

Related Books

Books by G. I. Gurdjieff

From the Foreword to the Reality of Being: The Fourth Way of Gurdjieff

Gurdjieff respected traditional religions and practices concerned with spiritual transformation, and pointed out that their different approaches could be subsumed under one of three categories: the "way of the fakir," which centers on mastery of the physical body; the "way of the monk," based on faith and religious feeling; and the "way of the yogi," which concentrates on developing the mind. He presented his teaching as a "Fourth Way" that requires work on all three aspects at the same time. Instead of discipline, faith or meditation, this way calls for the awakening of another intelligence—knowing and understanding. His personal wish, he once said, was to live and teach so that there should be a new conception of God in the world, a change in the very meaning of the word.

The first demand on the Fourth Way is "know thyself," a principle that Gurdjieff reminded us is far more ancient than Socrates. Spiritual progress depends on understanding, which is determined by one’s level of being. Change in being is possible through conscious effort toward a quality of thinking and feeling that brings a new capacity to see and to love. Although he said his teaching could be called "esoteric Christianity," Gurdjieff noted that the true principles of Christianity were developed thousands of years before Jesus Christ. It could also be called "esoteric Buddhism," as later studies have discovered. In order to open to reality, to unity with everything in the universe, Gurdjieff called for living the wholeness of "Presence" in the experience of "I Am."

When Gurdjieff undertook to write All and Everything, his trilogy on the life of man, he envisioned the last book as the Third Series titled Life Is Real Only Then, When "I Am." His stated aim for this book was to bring the reader to a true vision of the "world existing in reality.” Gurdjieff began work on it in November 1934 but stopped writing six months later and never completed the book. Before his death in 1949, he entrusted his writings to Jeanne de Salzmann, his closest pupil, and charged her with doing “everything possible—even impossible—in order that what I brought will have an action.