| The following article is from the Summer, 1993 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

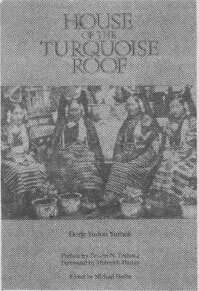

By Dorje Yudon Yuthok

Edited by Michael Harlin

Snow Lion Publications 330 pp. $14.95

Reprinted from Journal of Asian Studies, February 1993 Reviewed by Marcia Calkowski, The University of Lethbridge

This book makes a valuable contribution to the Tibetan ethnographic and historical record and to the burgeoning genre of women's narratives. Since autobiographies were (and are) rarely written by lay Tibetans, they afford precious glimpses into traditional Tibetan life that are excluded in Tibetan hagiographies. Dorje Yuthok's book, rich in vignettes of the quotidian life of Tibetan aristocrats prior to the Chinese invasion, reflects a sensitivity to readers' interests in finely drawn portraits of Tibetan social interaction, ritual observances, and material culture. In her selection of events, environments, and moods, Yuthok selects the appropriate generational lens through which readers may view her childhood, adolescence, or adulthood as she leads them through her life.

Yuthok comes from one of the most influential Tibetan families and thus was exposed to the more sophisticated and cosmopolitan circles in Tibetan society. Yuthok focuses on detailed descriptions of the intimacies of family life as well as on what might meet the eye of a spectator observing a ritual procession or a participant in a New Year's celebration. In doing so, she deftly conveys the immediacy of her experience to readers.

Yuthok begins with her birth to the Surkhang family, one of sixteen families belonging to the third rank of Tibetan aristocracy, during the unrest of 1912 when fighting between the Tibetan army and Manchu soldiers in Lhasa forced her mother to flee the city. She situates herself by outlining the privileges and duties assigned to the four aristocratic ranks and noting how these privileges and obligations shaped the professional and personal lives of her ancestors and immediate family. She follows celebrations of her childhood. In the process, Yuthok provides well-wrought descriptions of schoolroom discipline and instruction in Lhasa, the arrangement of New Year altars and festivities, and the sharply contrasting experiences of a pilgrim traveling in traditional Tibet.

Yuthok next turns to events that abruptly changed her life. One, an example of the complexities of aristocratic marriage and inheritance in traditional Tibetan society, is her departure from her family to become the heiress of a childless noble family; another is her marriage, followed by the loss of her first child and the births of ensuing children. Her frank narrative includes vicissitudes of her personal life, her escape from Tibet, and her immigration to the United States. She concludes fittingly with her pilgrimage to India, her joy at the discovery of the reincarnation of her guru, and, finally, with a reflection on the meaning of Buddhism for Tibetans, the ultimate context through which she would have us understand her life.

This book will assist any student of Tibetan culture and should also prove an illuminating addition to women's studies. Particularly valuable for ethnohistorians are the appendixes that provide the ranks and names of Tibetan noble families and delineate the Yuthok and Surkhang family trees.