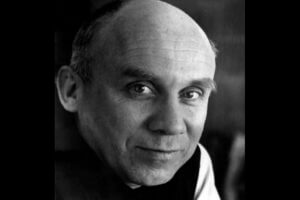

Thomas Merton, “Honorary Beatnik”

It’s hard to say exactly when Thomas Merton became an “Honorary Beatnik.” One could chase the association all the way back to the mid-thirties when, as an undergraduate at Columbia, he first became friends with the hipster Seymour Freedgood, the bohemian poet Robert Lax, and the painter Ad Reinhardt.

But it wasn’t until much later that Beat “icons” Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac, and Gary Snyder all admitted to being greatly influenced by Merton’s autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, published in 1948. Snyder even went so far as to say Merton’s autobiography convinced him to turn away from the study of anthropology for monasticism, Zen, and the contemplative life.

But if there is any “official” date when Merton became an “Honorary Beatnik,” it would have to be in the summer of 1961 when he contributed the lead poem to the premier issue of the first radical ecology publication The Journal for the Protection of All Living Beings, edited by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael McClure, and David Meltzer.

The poem Merton contributed, “Chant to be Used in a Procession around a Site with Furnaces” was later read by Lenny Bruce in his nightclub act. All the ensuing attention and notoriety earned Merton a rebuke from his abbot (James Fox) who told the monk he would not be allowed to publish in such journals again—primarily due to the “free” language of some of the other contributors (which included Norman Mailer, Bertrand Russell, Albert Camus, Michael McClure, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, et al.) Merton’s piece did not violate any Catholic teachings; the problem, Abbot Fox said, was that Merton’s association with the other writers threw an unsavory light upon the Order.

Merton, of course, did not agree but remained true to his vow of obedience and never published in the journal again.

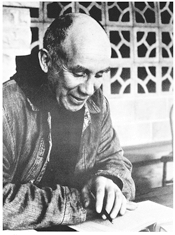

Merton's Thoughts on the Beats

Merton was, himself, ambivalent about the Beats as a literary movement, and although in 1963 he published a collection of poems, Emblems in a Season of Fury, clearly influenced by their work, he also wrote to a friend that year, “The protest of the Beatniks, while having a certain element of sincerity, is largely a delusion . . . . Yet this much can be said for them: their very formlessness may perhaps enable them to reject most of the false solutions and deride the ‘square’ propositions of the decadent liberalism around them. It may perhaps prepare them to go in the right direction.” (Courage for Truth, p. 170)

Merton soon came around to a greater appreciation of the Beats, for not long after, Merton published his own literary journal in 1968 titled Monk’s Pond, which included contributions by Jack Kerouac and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Merton’s death that year ended the conversation.

Even Mad Hepcats are Children of God

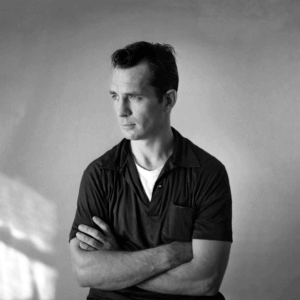

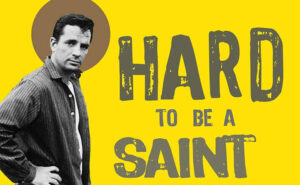

The popular conception of the Beats in general—and Kerouac in particular—has always been skewed toward the licentious and the sensational. Even to this day, Kerouac’s reputation as a no-nothing Bohemian addicted to vice and immorality confounds any true appreciation of his work as an artist and has led to a series of specious movies and “appreciations” that do him no justice.

Carolyn Cassady, wife of Neal Cassady and close friend of Kerouac, explained the problem rather succinctly when she wrote:

Young people felt Kerouac had given them a passport to selfish self-indulgence; they could now do anything that took their fancy. They abandoned homes and schools and threw the baby out with the bath water. They didn’t stop to think that Kerouac had no responsibilities and had to be free to roam in order to pursue his one aim—writing. He never meant to promote drug abuse, free love, or irresponsibility. When he was cast as “The King of the Beats” and “The Father of the Hippies,” he was shattered. He thought he was promoting love and appreciation of life in all its forms, a joyous celebration and awe derived from that love, with its ups and downs. He was basically very conventional, a gentleman of the old order who didn’t swear in mixed company nor talk about sex except with male cronies. He told me he was going to drink himself to death. I thought he was joking, but that is exactly what he did. [i]

Kerouac explained his aspirations as a writer this way:

I want to work in revelations not just spin silly tales for money. I want to fish as deep down as possible into my own subconscious in the belief that once that far down, everyone will understand because they are the same that far down. [ii]

And so, the novels and poems poured out of him, one after the other in an uncensored rain of both sacred and profane narratives, written in the first-bloom of their immediate discovery. When asked what any of this “soul searching” had to do with Beatniks or “mad hepcats,” Kerouac replied:

Even mad happy hepcats with all their kicks and chicks and hepcat talk are creatures of God laid out in this infinite universe without knowing what for. And besides, I have never heard more talk about God, the Last Things, and the soul, than among the kids of my generation—and not just the religious or the intellectual kids, but all of them. “What are you searching for?” they asked me. I answered that I was waiting for God to show his face. (Later I got a letter from a 16-year-old girl saying that was exactly what she’d been waiting for too.) [iii]