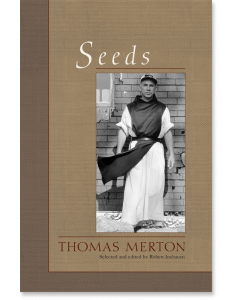

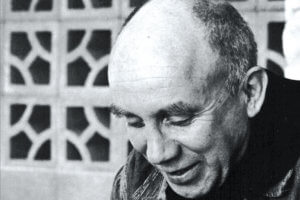

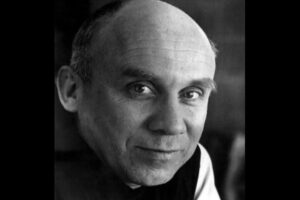

Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton (1915–1968) was a Trappist monk, spiritual director, political activist, social critic, and one of the most-read spiritual writers of the twentieth century. He is the author of many books, including The Seven Storey Mountain.

- Bestsellers Mindfulness 1 item

- Bestsellers Spiritual Paths 1 item

- Buddhist Anthology 1 item

- Buddhist Biography/Memoir 1 item

- Buddhist Ethics 1 item

- Buddhist History 1 item

- Buddhist Overviews 1 item

- Buddhist Philosophy 1 item

- Dependent Origination 1 item

- Four Immeasurables 1 item

- Four Noble Truths 1 item

- Insight Meditation 1 item

- Introductions to Buddhism 1 item

- Karma 1 item

- Southeast Asian Buddhism 1 item

- Way of the Bodhisattva 1 item

- Women in Buddhism 1 item

- Bodhisattva Path 1 item

- Dalai Lamas 1 item

- Death & Dying 1 item

- Kagyu Tradition 1 item

- Nyingma Tradition 1 item

- Shambhala Teachings 1 item

- Sutra 1 item

- Terma / Treasure Texts 1 item

- Chan/Chinese Zen 1 item

- Japanese Zen 1 item

- Women in Buddhism 1 item

- Zen art 1 item

- Self-compassion 1 item

- Workplace Mindfulness 1 item

- Haiku 1 item

- Love Poetry 1 item

- Spiritual Poetry 1 item

- Sufi Poetry 1 item

- Buddhist Poetry 1 item

- Yoga Teachers 1 item

- Yoga Philosophy 1 item

- Aikido 1 item

- Samurai 1 item

- Swordsmanship 1 item

- Nature & Environment 1 item

- Biography 2item

- Taoist Arts and Practices 1 item

- I-Ching 1 item

- Taoist Philosophy 1 item

- Eastern Philosophy 1 item

- Greek Philosophy 1 item

- Krishnamurti 1 item

- Kabbalah 1 item

- Christian Biography 3item

- Christian Contemplative Classics 1 item

- Christian Devotion 2item

- Christian Prayer 2item

- Thomas Merton 4item

- Leadership 1 item

- Writing 2item

- Japanese Culture 1 item

GUIDES

An Excerpt from On Thomas Merton

A Structured Approach

I very much regret that it took me so long to get to Merton’s journals.

There are seven volumes of them, over 2,500 pages—longer than the whole of Proust, whom I also read obsessively for years. I entered into Merton’s mind and heart, his lived life, in a way that was, like my reading of Proust, not like reading a book but having another life. As I would read a certain date that was important in my own life, I noted it: “first anniversary of my father’s death,” “my ninth birthday, I know I was miserable,” “I saw this book by Merton at the world’s fair.” I realized that the membrane between reading and living had grown dangerously thin when I got out of the bathtub one day and, seeing Merton’s alluringly smiling face on the cover of volume 5 on a nearby table, quickly covered myself with a towel.

The journals are Merton’s best writing because in them he found the form that best suited his gifts. In part this is because the journal format is in its essence, like so much about Merton, self-contradictory. A journal is theoretically a private record, but as Jonathan Montaldo, who edited volume 2 of the journals, says, by 1950 Merton had begun “blurring any line that might have previously existed between his journals as spontaneous diaries of remembrance and as conscious, semi-fictional reconstructions of the self, autobiography as a work of art.”1

It is a challenge to write coherently about a form that does not put a premium on coherence, that jumps from one subject to another, contradicts itself, revises itself, corrects itself, and admits its own delusions. As early as 1951 he notes that “this journal is getting to be the production of somebody to whom I have never had the dishonor of an introduction.”2

I approached the journals in two ways: I tried to understand what was constant throughout all the years, and also what showed evidence of development and change.

To the lamp on my desk, I pasted three index cards. They read ardent, heartfelt, headlong. Because whatever he wrote, even if he changed his mind the next day or in the next paragraph, his vibrating presence comes through in every word. Nothing is ever noncommittal or lukewarm. This is what makes Merton, and the journals, so intensely lovable and inspiring to those of us who are stumbling toward, if not Bethlehem, then Calvary.

On my computer I created files in which to place material from the journals in discrete categories: Merton and America, Merton and Europe, Merton and the Church, Merton and the Monastery, Merton and Politics, Merton and Nature, Merton Psychological Reflections, Merton Descriptions, Merton and God. It was a way of starting, but I couldn’t be rigid about my categories, because so many of them bled into one another. Where, I would ask myself, does this passage belong: Politics, the Monastery, or the Church? Or this one: Europe or the Monastery, America or the Church, Description or Psychological Reflection? Many of them that I put initially under one heading, I ended up copying into the largest file: Merton and God.

Whatever he wrote, even if he changed his mind the next day or in the next paragraph, his vibrating presence comes through in every word. Nothing is ever noncommittal or lukewarm.

Descriptive Writing

It was easiest to begin with the file “Merton Descriptions” because his talent for description is his greatest. When his senses are fully engaged, his writing comes most vividly alive. To my mind—and I know there are many who will disagree with me—he is weakest when he is trying to sustain an argument. I detect a much greater sense of spiritual vitality in his journal passages than I do in his books that are self-consciously “spiritual.” In those, I feel the strain, an excessive abstraction that leads to flaccid and disembodied language. But from the very first pages of the journals, everything he describes using sensory language shimmers and resonates.

His writings on nature are well known and widely treasured, and their strength lies in their capturing of disparate elements, netting them in an image that startles and satisfies. This gift does not diminish throughout the decades.

On December 2, 1948, he writes:

A thousand small high clouds went flying majestically like ice-floes, all golden and crimson and saffron, with clean blue and aquamarine behind them, and shades of orange and red and mauve down by the surface of the land where the hills are just visible in a pearl haze and the ground was steel-white with frost—every blade of grass as stiff as wire.3

Ten years later, he presents us with a marvelously ominous description of the night sky.

March 15, 1959

The sky before Prime, in the West, livid, “blasted”—fast-running dark clouds, pale spur of the firetower against the black West.4

The sky is undomesticated here, far from Wordsworthian, a sky looked at with the eye of one up late, or early, but wide, wide awake.

His ability to yoke two unlikes—the hallmark of successful metaphor or simile—are evident in two passages from 1964:

April 24, 1964

Large dogwood blossoms in the wood, too large, past their prime, like artificial flowers made out of linen.5

April 28, 1964

There was a tanager singing like a drop of blood in the tall thin pines.6

Often, he makes the natural more apprehensible by comparing it to something inorganic or man-made: “the moon . . . dimly red, like a globe of almost transparent amber”; “waves of hills flying away from the river, skirted with curly woods or half-shaved like the backs of poodles”;7 “a puddle in the pig lot shines like precious silver”; “pillared red cliffs, ponderous as the great Babylonian movie palaces of the 1920s.”8

His writings on nature are well known and widely treasured, and their strength lies in their capturing of disparate elements, netting them in an image that startles and satisfies.

I notice the number of times violent images connect with beauty: “the tanager . . . like a drop of blood”; “the sun . . . under a shaggy horn of blood”;9 “the pines were black . . . a more interesting and tougher murkiness”;10 “smoke rising up from the valley, against the light, slowly taking animal form . . . menacing and peaceful”;11 “they lighted the orchard heaters to fight against smoke, and the farm looked like a valley in hell”;12 “Claws of mountain and valley. Swing and reach of long, gaunt, black, white forks.”13

So much for Milosz’s criticism that Merton was an overly optimistic romantic when it came to nature.

On Travel

In the last year of his life, when he was allowed to travel more than he had for many years, he took great pleasure in the new landscapes that presented themselves to him. From a plane he wrote,

May 6, 1968

Whorled dark profile of a river in snow. A cliff in the fog. And now a dark road straight through a long fresh snow field. Snaggy reaches of snow pattern. Claws of mountain and valley. Light shadow or breaking cloud on snow.14

Merton’s ambivalence about whether or not Gethsemani is the place he wants to end his life finds its expression in his response to the trees of the West Coast and the trees of Kentucky.

May 30, 1968

I arrived back here in Kentucky in all this rain. The small hardwoods are full of green leaves, but are they real trees?

The worshipful cold spring light on the sandbanks of the Eel River, the immense silent redwoods. Who can see such trees and bear to be away from them? I must go back. It is not right that I should die under lesser trees.15

One of the sadnesses surrounding Merton’s death is that this man who was so nourished by the created world died under no trees at all, but in a bathroom.

I wondered what he would have made of it if the accident had been just an accident, not a fatality. He might have been funny about the absurdity of the situation: he was often very funny. He might have given us a fine description of a bathroom in Bangkok: his gift for description wasn’t limited to the natural world. He could conjure a place, a room, a public or private space with a few details—using not only his eyes and ears but his nose, skin, and fingertips. In 1940 he described a Miami hotel:

Venetian blinds, stone floors, coconut palms making a green shade . . . The smell is a sort of musty smell of the inside of a wooden and stucco building cooler inside than out . . . a smell that has something of the beach about it too, a wet and salty bathing-suit smell . . . of dry palm leaves, suntan oil, rum, cigarettes. It has something of the mustiness of that immense and shabby place in Bermuda, the hotel Hamilton . . . also like the Savoy Hotel in Bournemouth, which stood at the top of a cliff overlooking a white beach on the English Channel. It had fancy iron balconies, and even when the dining room was full you could feel the blight of winter coming back upon it, and knew very well how it would look all empty, with all the chairs stacked.16

His description of a restaurant in Lexington—caustic, ferociously observant—accomplishes what the best of his journals do: the creation of a whole world, an atmosphere, a set of characters, in a few words.

April 6, 1968

Lum’s in Lexington. Red gloves, Japanese lights. Beer list. Bottles slipped over counter. Red waistcoats of Kentucky boy waiters. Girl at cashier desk the kind of thin, waiflike blonde I get attracted to. Long talk with her getting directions on how to get to Bluegrass Parkway. While we were eating a long, long freight train went by, cars on high embankment silhouetted against a sort of ragged vapor sunset. A livid light between clouds. And over there a TV with . . . the jovial man in South Africa who just had the first successful heart transplant. . . . He had an African Negro’s heart in him, beating along. They asked him if he felt any different towards his wife and I really fell off my chair laughing. No one else could figure out what was funny.

When I was in Lum’s, I was dutifully thinking, “Here is the world.” Red gloves, beer, freight trains. The man and child. The girls at the next table, defensive, vague, aloof. One felt the place was full of more or less miserable people. Yet think of it: all the best beers in the world were at their disposal and the place was a good idea. And the freight train was going by, going by, silhouetted against an ambiguous sunset.17

Merton’s compassion and tenderness toward the poor and the marginalized shows itself in tender but piercing snapshots, revealing that his political convictions had their roots in a deep and wide human sympathy. He describes the journey of a black junkman:

November 6, 1950

The willows were like silver this morning. . . . A junk wagon came along. . . . The wagon seemed to be all bells, like a Chinese temple. . . . The mule was flashing with brass disks. . . . The wagon . . . had something of the lines of a Chinese junk [seaship]. . . . On top of it all sat the driver with his dog. Both were immobile. They sailed forward amid their bells. The dog pointed his nose straight forward like an arrow. The negro captain sat immersed in a gray coat. He did not look right or left, and I would have approached, with great respect, what seemed to be a solid mysticism. But I stood a hundred yards off, enchanted by the light on the mule’s harness, enchanted by the temple bells.18

His rendering of the suffering of a child caught in a fire is worthy of James Agee:

March 19, 1959

After the fire . . . a little boy with a pathetic face and holes in his pants, whom I had seen some weeks before with an ugly scar on the side of his head. The big scab was gone and you could see the place of the scar. His face made you wonder if he ever had anything happen to him in life worth smiling about.19

Merton’s compassion and tenderness toward the poor and the marginalized shows itself in tender but piercing snapshots. . .

It’s not surprising that Merton wrote on December 18, 1939, “I have always been fond of guide books. As a child I read guide books to the point where it became a vice. I guess I was always looking for some perfect city.”20

Perhaps New York was the closest he came to that “perfect city”; his palpable delight in his return after more than twenty years away bursts out in every word:

July 10, 1964

Riding down in the taxi to the Guggenheim Museum around one o’clock, through the park, under tunnels of light and foliage. . . . The people walking on Fifth Avenue were beautiful, and there were those towers! The street was broad and clean. A stately and grown-up city! A true city, life-size. A city with substance and scale, large and right. Well lighted by sun and sky, anything but soulless, and it is feminine. It is she, this city. I am faithful to her! I have not ceased to love her.21

Notes

1. Merton, Entering the Silence, 394, fn 50.

2. Merton, Entering the Silence, 458.

3. Merton, Entering the Silence, 248.

4. Merton, Search for Solitude, 268.

5. Merton, Dancing in the Water, 99.

6. Merton, Dancing in the Water, 100.

7. Merton, Search for Solitude, 6.

8. Thomas Merton, The Other Side of the Mountain: The End of the Journey, Volume Seven 1967–1968, The Journals of Thomas Merton, ed. Patrick Hart (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1999), 106.

9. Merton, Other Side, 70.

10. Merton, Other Side, 33.

11. Merton, Turning Toward the World, 74.

12. Merton, Entering the Silence, 195.

13. Merton, Other Side, 94.

14. Merton, Other Side, 94.

15. Merton, Other Side, 112.

16. Thomas Merton, Run to the Mountain: The Story of a Vocation, Volume One 1939–1941, The Journals of Thomas Merton, ed. Patrick Hart (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996). 162.

17. Merton, Other Side, 78.

18. Merton, Entering the Silence, 438.

19. Merton, Search for Solitude, 270.

20. Merton, Run to the Mountain, 113.

21. Merton, Dancing in the Water, 125.

Share

Related Books

A Quality of Being

By Dave O’Neal

We talk with Roger Lipsey about his book Make Peace Before the Sun Goes Down: The Long Encounter of Thomas Merton and His Abbot, James Fox

2018 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the death of the most famous Trappist monk of modern times—or perhaps of all time—Thomas Merton. From his life of extreme silence and seclusion he became a pioneer in the religious dialogue between East and West, a force in the intellectual and political life of his era, and a beloved spiritual writer, whose influence has only increased in the years since his death. Roger Lipsey, a Merton scholar and author of a book analyzing a particular relationship from the last two decades of Merton’s life, took the time to have a conversation with us about the relationship portrayed in the book, and also about Merton and what he continues to mean for us today.

Dave O’Neal: Thomas Merton was certainly among the best known of Catholic writers of the last century, but Dom James Fox, the other subject of your book, is far less widely known. Who was he?

Roger Lipsey: Dom James (1896-1987) was abbot of Our Lady of Gethsemani in central Kentucky, the large monastery where Thomas Merton had been a member of the community since 1941. Elected abbot in 1948, Don James continued in that role until a year before Merton’s death in 1968. Born to a large working class family, Irish, in a Boston suburb, young James was a brilliant student who attended Harvard College on scholarship, graduated in three years, and spent another few semesters at Harvard Business School. His burning ambition at the time was to succeed in the business world, but there was something else in him, deeply religious, touched to the core by retreats he had made with the Passionist Fathers in the Boston area. Deciding to give his life to the Church and to monastic life, he became a Passionist but within a few years felt that its public teaching mission wasn’t a good fit. He needed greater solitude, a quieter life of prayer. Transferring to the Trappist Order—Gethsemani’s Order—he soon stood out as both a man of strong religious life and a gifted organizer. He came to Gethsemani as abbot when the community was failing financially. He turned that situation around within a few years. Gethsemani became his enterprise, and it began to thrive. It also attracted, in the late 1950s and early '60s, waves of vocations—predominantly young novices, at their greatest number a little more than 250, so many that a sort of tent city had to be set up for them in the “préau,” the once tranquil central garden at the heart of the monastic complex.

Why did so many hopeful men come to Gethsemani? In part, after World War II, many Catholic veterans had seen more than enough of “the world” and wanted something far different for themselves. But the strongest reason for their arrival at Gethsemani was Thomas Merton’s stunningly precocious, brilliantly written memoir of his own path to monastic life: The Seven Story Mountain.

Merton was a literary artist, a free and vastly creative spirit voluntarily subsumed to strict monastic discipline. Dom James was in many respects a nineteenth-century abbot, strict and traditional. They were destined to clash, seriously so, though they were also capable of cooperating on some issues of common interest, notably the education of the novices, for which Dom James made Merton responsible.

DO: How did you first become interested in Thomas Merton yourself?

RL: In 1982 I visited the Thomas Merton Center and Gethsemani for the first time, drawn by Merton’s abstract brush drawings and print. They were unstudied, even ignored—a few were used here and there as illustrations in new editions of his books. It took years more for me to turn toward writing Angelic Mistakes: The Art of Thomas Merton, for you, sir—for Shambhala. But by then my life had changed. I had joined Merton in the zone of convergence. It was no longer only his visual art that mattered to me; it was his entire realization of the life of search, of a spirituality that is sure enough of itself and of its direction to welcome uncertainty, to welcome others.

DO: The relationship between Merton and Dom James has long been known to be complicated, but you were able to chronicle the complications in a kind of detail that hadn’t happened before—did you have access to materials other scholars hadn’t yet seen?

RL: Yes, masses of archival material in two categories: already available but unstudied, and newly available through the kindness and trust of the current abbot of Gethsemani. Historians are archive people—archives are their joy because history or biography is strewn in archives, at best summarily ordered, probably unknown and in no particular order. You strive to assemble a coherent and true life story from, let’s say, debris left behind. You have to question the material, follow connections where they lead, let the story dissolve and re-form a number of times over as the material shows what it needs to be. The Merton archive at the Thomas Merton Center, Bellarmine University, Louisville, Kentucky, is a model of order—but so vast that much material in it remains to be studied and interpreted. The archives at the abbey itself, crucial to this book, were at the time of writing less well ordered but still entirely usable, deeply interesting.

DO: The book contains a very striking frontispiece illustration. Can you describe it, and say something about what it reveals about both Merton and Dom James?

RL: The frontispiece is an early page of a new Merton book (The Sign of Jonas, 1953) on which both Merton and Dom James wrote dedicatory words to a Trappist abbot in Canada, whom they both knew and obviously respected. The character of each man is evident on that page: Merton’s handwriting light and modest, expressing in French his “religious and filial homage in Our Lady,” Dom James’s handwriting expressing vigorously in English his “gratitude, affection, and assurance of our continual prayer.” But then there is something more from Dom James, a stamp he often added to his communications, just like the stamps we use for Air Mail or a return address. It reads: “All for Jesus, Thru Mary, with a Smile.” This was Dom James, a man of simple, direct, unintellectual faith. Within a few months of his abbacy, Merton had privately joked in his journal that he was going around the monastery with a smile.

DO: Merton was an unusual monk in many ways: a man vowed to the silent life who carried on an exhaustive correspondence with some of the great figures of his time; a hermit with an amazing number of friends. How unusual was he among Trappists of his era?

RL: Father Louis—as Merton was known across the Trappist world—was unique. There were writers and scholars in the Order; I’m thinking particularly of Fr. Chrysogonus Waddell (1930–2008), a widely respected musicologist and composer to whom Gethsemani owes many of its utterly beautiful “psalm tone” chants that are heard there daily. But there was no second Merton. His brilliant witness to the life of prayer, of intelligent sacrifice, of life as a Way that grips us but also raises us, remains for all to read, a source of inspiration. My book offers a fair amount of comment on where to look for Merton at his best in his autobiographical memoirs, his journal, correspondence (remarkable!), essays, and more.

DO: Can you give some idea of the breadth of Merton’s interests—in the social, religious, artistic, theological, or literary realms—during the period covered in the book?

RL: Oh my . . . He belonged to so many different worlds, contributed to so many different worlds. He was remarkable, and prescient, on the future of monasticism. He was a Western pioneer, recognized and befriended by D.T. Suzuki on Zen and its commonalities with Christianity. He was a fast friend of the Berrigan brothers, particularly of Dan Berrigan, in the anti-war movement of the 1960s, and he was regarded by the Berrigans and others in the movement as their spiritual counsel, their rudder in rough seas. He had a strong and searching prayer life structured initially around the insights of St. John of the Cross, the sixteenth-century mystic and monastic, and later a prayer and contemplative life that owed much to Zen. “How I pray is breathe,” he once wrote in the mid-1960s. And then, he explored the hermit life, argued for it from ancient Trappist lives and texts, and eventually lived it in his famous hermitage in the woods at Gethsemani. And then, and then. . . There is really so much. I should mention that in the early to mid 60s he explored abstract art through brush drawings and prints. Shambhala published my study of that aspect of Merton’s creative work: Angelic Mistakes: The Art of Thomas Merton. I’m happy to report here that Echo Point Books will soon republish that book.

DO: What was the Merton of the Dom James years (1950s and 60s) like—compared to the Merton so many have encountered in his best-selling memoir The Seven Story Mountain?

RL: You could say that there were three periods in Merton’s life and works. The Seven Storey Mountain, published in 1948 and a bestseller, crowned and completed the first period. Through those years he was somewhat ascetic, strongly, strongly Catholic, and a marvelously gifted witness to his own life in all of its breadth and emotions. In the mid-1950s, he responded willingly to pressure from Dom James and James’s superior in the Order in Europe to write much less and to adhere to properly Catholic topics intended for that community’s readers. Broadly speaking, the published works of that middle period are restrained; one hardly knows that Merton is their author. But his correspondence and private journal in those years remain immensely vital and searching. The third period, from about 1961 to his untimely death in 1968, is, so to speak, “my Merton,” and I hope yours. He is so interesting, so searching, so free of mind but religiously grounded, so centered in his poetic and interpretive abilities as an author. Wherever one looks—in essays, the journal, correspondence, elsewhere—he is a paradigmatic seeker, thinker, explorer of our shared reality and its innate spiritual dimensions.

DO: Can the relationship between Merton and Dom James be seen to symbolize something bigger than both men? Of course one can see the conflict between a Roman Catholicism that clung hard to tradition versus the openness that was happening in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, but is there a symbolism even greater, more “cosmic” than that?

RL: I think you’re right about this. The drama between them isn’t limited to “Catholics then,” or “the Church,” or any imaginable boundary. It is the drama of an immensely creative, searching—and, on occasion, undisciplined—spirit encountering limits set again and again by traditional, conservative attitudes and regulations. Merton’s path toward himself is a sign to us all.

DO: To what degree do you believe that Merton and Dom James were reconciled by the time of Merton’s death? Was there a sincere sort of healing that took place or was it more like “making nice” once they were no longer locked in a relationship of obedience?

RL: What to say here? They were both monks, both committed to the Cistercian way—and they knew that. That was a bond between them. On the other hand, Dom James’s endless restrictions on Merton were onerous, and Merton knew that, detested that. In all the years of Dom James’s abbacy, Merton was permitted to leave the monastery for more than one day on, I think, three occasions (apart from hospital stays). Yet he was justly in demand around the world. Dom James stood in the way.

DO: Do you believe Merton would have remained a monk all of his days, had his life not been cut so tragically short?

RL: As I write toward the end of my book, Merton had discussed with Trungpa Rinpoche, then young, in Delhi, the possibility of cofounding a monastery of a new kind, dedicated to meditation, profoundly inter-religious, and profoundly serious. Perhaps in the American southwest. I believe he would have moved toward that. Would he have remained a Cistercian monk and priest? I must say, I hope so: it suited him, it was a perfect identity for this man of immense good will and sensibility.

DO: How would you characterize Merton’s legacy, from the perspective now of half a century after his death?

RL: I don’t feel that it matters so much anymore whether one is Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim—and so on. What matters now is how one goes about it, how deeply it is felt, how one acts in relation to it, what inner identity it helps one to nurture and realize over time. There is a convergence, as one of my closest friends puts it, and in that zone of convergence it’s not labels and dogmas that matter, and it’s certainly not passionate advocacy. It is quality: quality of being, quality of action toward others, quality of wisdom and common sense intertwined. Merton already occupied that zone of convergence in his later years. In effect, he waits for us there.