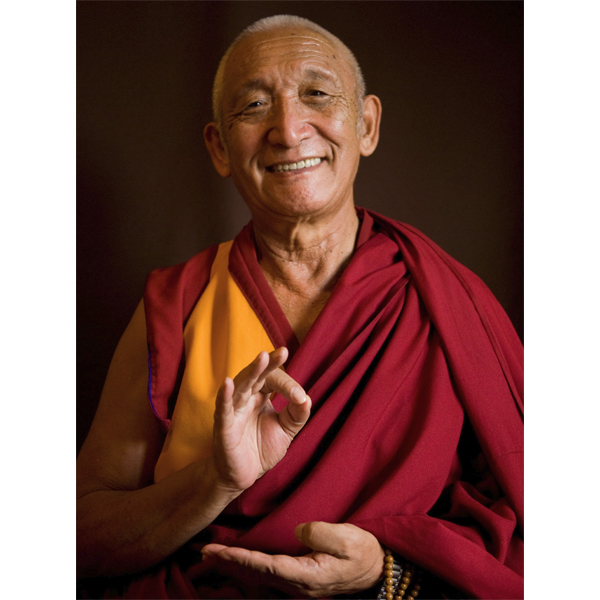

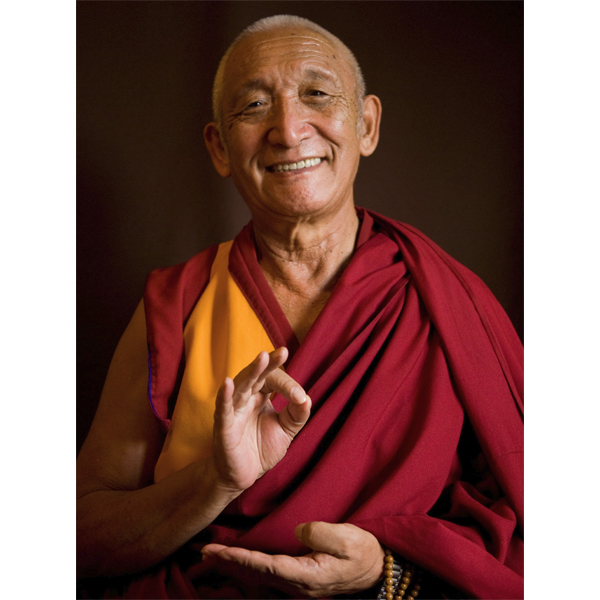

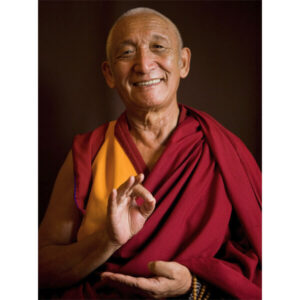

Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Geshe Sonam Rinchen (1933–2013) studied at Sera Je Monastery and in 1980 received the Lharampa Geshe degree. He taught Buddhist philosophy and practice at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala, India, as well as in dharma centers around the world.

Geshe Sonam Rinchen

-

The Three Principal Aspects of the Path$21.95- Paperback

The Three Principal Aspects of the Path$21.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way$39.95- Paperback

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way$39.95- PaperbackBy Aryadeva

By Gyel-tsap

By Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

Eight Verses for Training the Mind$18.95- Paperback

Eight Verses for Training the Mind$18.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

How Karma Works$22.95- Paperback

How Karma Works$22.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

The Heart Sutra$22.95- Paperback

The Heart Sutra$22.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

The Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas$19.95- Paperback

The Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas$19.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

The Bodhisattva Vow$22.95- Paperback

The Bodhisattva Vow$22.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

The Six Perfections$21.95- Paperback

The Six Perfections$21.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

Translated by Ruth Sonam -

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment$19.95- Paperback

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment$19.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

By Atisha

Translated by Ruth Sonam

- Buddhist Philosophy 1 item

- Dependent Origination 2item

- Four Noble Truths 1 item

- Heart Sutra 1 item

- Introductions to Buddhism 3item

- Karma 1 item

- 37 Practices 1 item

- Bodhisattva Path 4item

- Prajnaparamita 1 item

- Gelug Tradition 1 item

- Kadam Tradition 2item

- Lam Rim 1 item

- Lojong/Mind Training 1 item

- Madhyamaka 1 item

- Sutra 1 item

GUIDES

The Heart Sutra: A Reader's Guide

This is part of a series of articles on the arc of Zen thought, practice, and history, as presented in The Circle of the Way: A Concise History of Zen from the Buddha to the Modern World. You can start at the beginning of this series or simply explore from here.

The Heart Sutra stands among the classic Buddhist scriptures. Akin in importance to the “Shema Yisrael” for Jews or the “Lord’s Prayer” for Christians, the Heart Sutra is considered by Mahayanists, and especially Chan and Zen Buddhists, to contain the pith instructions for the practice of their religion—namely the radical negation of conventional concepts and extreme views in favor of an experience of reality permeated by wisdom and compassion.

"Heart Sutra" is a translation of the Sanskrit term Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya, which more fully translates to “The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra.” Along with the Diamond Sutra, it is the most famous representative of the Prajñāpāramitā (Perfection of Wisdom) section of the Mahayana Buddhist canon. The sutra has been translated into English from Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mongolian, and Chinese canonical sources and exists in both a long and a short form—the short version consisting, incredibly, of only fourteen lines of Sanskrit or 260 Chinese characters.

The key to its brevity is the sutra’s single-pointed focus on negation of conventional understanding. Indeed, this iconoclastic text goes so far as to negate the core teachings of the Abhidharma (the orthodox Theravadin collection of texts interpreting the sutras) and of the Buddha himself—the Four Noble Truths, the Five Skandhas (aggregates), the Eighteen Dhātus (senses, sense objects, and fields of sense perception), and the Twelve Links of Dependent Co-Arising. The Heart Sutra holds that those who allow practice to carry them through and beyond even these wisdom concepts will find “wisdom beyond wisdom,” a far shore of awakening where one is not caught by fixed ideas and therefore can escape all suffering.

Although the Heart Sutra is mentioned in more Shambhala Publications books than can be listed here, interested readers can find various translations and in-depth analyses of the sutra in the following Shambhala books.

Explore Zen Buddhism: A Reader's Guide to the Great Works

Overview

Chan in China

- The Works of the Chan and Zen Patriarchs

- The Works of Zen in the Tang Dynasty (618-907)

- The Works of Zen in the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279)

- The Great Koan Collections

Zen in Korea

Zen in Japan

- Early Zen in Japan

- Dogen: A Guide to His Works

- Rinzai Zen

- Hakuin Ekaku: A Reader's Guide

- The Samurai and Zen

- Zen in Japan up to the Meiji Restoration

Additional Resources

>The Heart Sutra: A Reader’s Guide

- Zen in the Modern World (Coming Soon)

- Foundational Sutras and Texts of Zen (Coming Soon)

- Zen and Tea

The Heart Sutra in Zen and Chan Buddhism

"The Heart Sutra resonates with meditation and a meditative way of life in a way that is as extraordinary as it is profound. Without doubt this is why it is often recited at meditation gatherings and at many Buddhist ceremonies. What, then, are the essential teachings of the Heart Sutra? What is its significance for practitioners of meditation today?"

-From The Heart Sutra, by Kazuaki Tanahashi

Painting Enlightenment: Healing Visions of the Heart Sutra

By Paula Arai

The Heart Sutra—among the most famous of Buddhist scriptures—has been treated with reverence for centuries. Practitioners and calligraphers have honored the sutra by hand copying it dozens, hundreds, and even thousands of times. Bringing that tradition into the modern era, Japanese artist Iwasaki Tsuneo (1917–2002) created an original and exquisitely intricate body of Buddhist art. The subject of his paintings range from classical Buddhist iconography to majestic views of our universe as revealed by science—all created with painstakingly rendered miniature calligraphy of the Heart Sutra.

Zen Words for the Heart: Hakuin's Commentary on the Heart Sutra

Translated by Norman Waddell

Hakuin Zenji (1689-1769) was one of the most important of all Japanese Zen masters. His commentary on the Heart Sutra is a Zen classic that reflects his dynamic teaching style, with its balance of scathing wit and poetic illumination of the text. Hakuin's sarcasm, irony, and invective are ultimately guided by a compassion that seeks to dislodge students' false assumptions and free them to realize the profound meaning of the Heart Sutra for themselves. The text is illustrated with Hakuin's own calligraphy and brush drawings.

The Heart Sutra: A Comprehensive Guide to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism

By Kaz Tanahasi

There is no better introduction to the Heart Sutra than this guide by Kaz Tanahashi. A lifelong translator and calligrapher working at the peak of his powers, Tanahashi outlines the history and meaning of the text and analyzes it line by line in its various forms (Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Tibetan, Mongolian, and several key English translations). The result is a deeper understanding of the history and etymology of the sutra’s elusive words than is generally available to the non-specialist—yet with a clear emphasis on the relevance of the text to practice.

The Heart Sutra: A Comprehensive Online Course to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism by Kazuaki Tanahashi

For Zen Buddhists—and many others—the sutra expresses the nature of reality in ways both profound and paradoxical. In this online course, Kazuaki Tanahashi and Roshi Joan Halifax collaboratively explore the depths of the sutra’s teaching through talks, chanting, readings, and group discussions.

Using Kaz’s book The Heart Sutra: A Comprehensive Guide to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism as its text, this course delves deep into the history and lived experience of the Heart Sutra, posing questions and drawing connections to help you integrate this precious teaching into your daily life and awareness, whether you are encountering the sutra for the first time or have chanted it for decades. We invite you to join these two remarkable and wise teachers in exploring the boundless nature of all existence through this core text.

Infinite Circle: Teachings in Zen

Beloved American Zen teacher Bernie Glassman takes the Heart Sutra (along with another key Zen text, The Identity of Relative and Absolute) as his focus in this succinct, down-to-earth volume.

“We see Bernie as one body, but somehow we’re unable to see the whole universe as one body,” he writes. “By seeing our true nature we realize the emptiness of all five conditions and are freed of pain. The last line or mantra of the Heart Sutra is ‘Gone, gone, have gone, altogether have gone!’ Gone where? Here.”

Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo

By Zen Master Dogen

Edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi

While not a full work, the first chapter of Dogen's magnum opus, the Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, is on the Heart Sutra. The essay is entitled Maka Hannya Haramitsu and translated as Manifestation of Great Prajna.

From the introduction of Treasury of the True Eye:

Dogen delivered “Manifestation of Great Prajna” as a dharma talk to the Kannondori community, the first text in the series of Shōbō Genzō. The official title of the original text is “Shōbō Genzō Maka Hannya Haramitsu.” (The following fascicles of Shōbō Genzō are similarly titled.)

This is a commentary on the Prajna Heart Sutra, one of the most commonly recited scriptures in East Asia. The Heart Sutra is regarded as a brief condensation of the entire Mahayana teaching of shunyata (emptiness or boundlessness). Its mantra at the end was often believed to have wish-granting magical power in Esoteric Buddhism.

In this fascicle, Dogen challenges the traditional analytical views of phenomena, asserting that all elements are interrelated. Not mentioning the mantra, he hints at his own aversion for highly ritualized and benefit-oriented Esoteric practices. Dogen placed this text second in his seventy-five-fascicle version of the Treasury of the True Dharma Eye.

Continue to the next article in the series: Zen in the Modern World (Coming Soon)

Return to Zen Buddhism: A Readers Guide to the Great Works

or discover more related to the Heart Sutra in Buddhist thought below

The Heart Sutra and the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) Sutra in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism

"The Buddha is said to have given eighty-four thousand different teachings, the essence of which is contained in the Perfection of Wisdom sutras, of which the Heart Sutra is the most concise version. The Perfection of Wisdom sutras explain the most subtle and fundamental way in which things exist."

-from The Heart Sutra: An Oral Teaching by Geshe Sonam Rinchen, translated by Ruth Sonam

The Prajnaparamita Sutras, The Ornament of Clear Realization, and Their Tibetan Commentaries

Translated by Karl Brunnholzl

The Abhisamayalamkara summarizes all the topics in the vast body of the Prajnaparamita Sutras. Resembling a zip-file, it comes to life only through its Indian and Tibetan commentaries. Together, these texts not only discuss the "hidden meaning" of the Prajnaparamita Sutras—the paths and bhumis of sravakas, pratyekabuddhas, and bodhisattvas—but also serve as contemplative manuals for the explicit topic of these sutras—emptiness—and how it is to be understood on the progressive levels of realization of bodhisattvas. Thus these texts describe what happens in the mind of a bodhisattva who meditates on emptiness, making it a living experience from the beginner's stage up through buddhahood.

Gone Beyond (Volume 1): The Prajnaparamita Sutras, The Ornament of Clear Realization, and Its Commentaries in the Tibetan Kagyu Tradition

Translated by Karl Brunnholzl

Gone Beyond contains the first in-depth study of the Abhisamayalamkara (the text studied most extensively in higher Tibetan Buddhist education) and its commentaries in the Kagyu School. This study (in two volumes) includes translations of Maitreya's famous text and its commentary by the Fifth Shamarpa Goncho Yenla (the first translation ever of a complete commentary on the Abhisamayalamkara into English), which are supplemented by extensive excerpts from the commentaries by the Third, Seventh, and Eighth Karmapas and others. Thus it closes a long-standing gap in the modern scholarship on the Prajnaparamita Sutras and the literature on paths and bhumis in mahayana Buddhism.

Gone Beyond (Volume 2): The Prajnaparamita Sutras, The Ornament of Clear Realization, and Its Commentaries in the Tibetan Kagyu Tradition

Translated by Karl Brunnholzl

Gone Beyond contains the first in-depth study of the Abhisamayalamkara (the text studied most extensively in higher Tibetan Buddhist education) and its commentaries in the Kagyu School. This study (in two volumes) includes translations of Maitreya's famous text and its commentary by the Fifth Shamarpa Goncho Yenla (the first translation ever of a complete commentary on the Abhisamayalamkara into English), which are supplemented by extensive excerpts from the commentaries by the Third, Seventh, and Eighth Karmapas and others. Thus it closes a long-standing gap in the modern scholarship on the Prajnaparamita Sutras and the literature on paths and bhumis in mahayana Buddhism.

When Clouds Part: The Uttaratantra and Its Meditative Tradition as a Bridge between Sutra and Tantra

Translated by Karl Brunnholzl

“Buddha nature” (tathāgatagarbha) is the innate potential in all living beings to become a fully awakened buddha. This book discusses a wide range of topics connected with the notion of buddha nature as presented in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism and includes an overview of the sūtra sources of the tathāgatagarbha teachings and the different ways of explaining the meaning of this term. It includes new translations of the Maitreya treatise Mahāyānottaratantra (Ratnagotravibhāga), the primary Indian text on the subject, its Indian commentaries, and two (hitherto untranslated) commentaries from the Tibetan Kagyü tradition.

The Heart Sutra: An Oral Teaching

By Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Translated and Edited by Ruth Sonam

This short gem of a book shows how distorted perceptions and disturbing emotions―arising from our misunderstanding of reality―can be completely uprooted, resulting in a freedom from suffering. Understanding the nature of reality is the key to liberation. The wonderfully concise Heart Sutra is considered the essence of the Buddhas' teachings.

The author's long experience in teaching Western students at the Dalai Lama's Library of Tibetan Works and Archives makes The Heart Sutra an ideal introduction for Westerners to this important subject.

Read an Excerpt from the Book

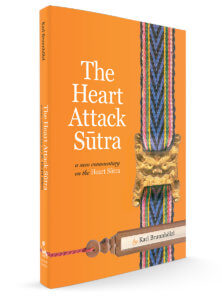

The Heart Attach Sutra: A New Commentary on the Heart Sutra

The radical message of the Heart Sūtra, one of Buddhism's most famous texts, is a sweeping attack on everything we hold most dear: our troubles, the world as we know it, even the teachings of the Buddha himself. Several of the Buddha's followers are said to have suffered heart attacks and died when they first heard its assertion of the basic groundlessness of our existence—hence the title of this book. Overcoming fear, the Buddha teaches, is not to be accomplished by shutting down or building walls around oneself, but instead by opening up to understand the illusory nature of everything we fear—including ourselves. In this book of teachings, Karl Brunnhölzl guides practitioners through this 'crazy' sutra to the wisdom and compassion that lie at its core.

![By Daderot [CC0 or CC0], from Wikimedia Commons](/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Capture.jpg)

At the age of sixteen Tsongkhapa left Amdo to pursue his quest for knowledge in central and southern Tibet, where he studied with more than fifty prominent teachers. Between 1374 and 1376 he concentrated on the Perfection of Wisdom sutras and on the five treatises of Maitreya along with the many commentaries devoted to them. He gained a rigorous intellectual training and a wide knowledge of both sutra and tantra during this period. Tsongkhapa was already determined to combine scholarship with the practice of both sutra and tantra and he continued to receive tantric empowerments from a number of important masters belonging to different traditions.

He was dedicated to developing the correct understanding of reality and at this time had a significant experience of entering a profound state of meditation during a ceremony when the assembled monks were reciting a Perfection of Wisdom sutra. He remained deeply absorbed long after the cer emony was over and the other monks had left the hall. From his twenty-second year he began to study intensively the works on valid cognition by Dignaga and Dharmakirti and was deeply impressed and moved by the efficacy of Dharmakirti's system of reasoning.

For the next eleven years Tsongkhapa travelled from one monastic college to another deepening his philosophical knowledge and giving teachings. His main teacher and close friend during this period was the Sakyapa (Sa skya pa) master Rendawa Shönu Lodrö (Red mda' ba gZhon nu Blo gros).

At the age of thirty-three he met with the remarkable Lama Umapa (dBu ma pa), who came to Tsang (gTsang) with the intention of studying with Tsongkhapa. Umapa had had a vision of Manjushri, the embodiment of enlightened wisdom, which had changed his life from that of a simple cowherd. As a result of this vision he took up practices related to Manjushri and eventually experienced Manjushri's constant presence.

Lama Umapa became Tsongkhapa's direct line of communication with Manjushri. They spent periods of retreat together during which Umapa conveyed to Tsongkhapa Manjushri's advice and responses to questions concerning the correct understanding of reality. Eventually Tsongkhapa himself experienced visions of Manjushri, who bestowed empowerments on him and gave him teachings.

During the winter of 1392-1393 in accordance with Manjushri's instructions he stopped teaching and withdrew from other public activities to concentrate on a period of intense meditation. He was joined by a group of eight carefully chosen students. Living austerely, they began practices for purification and the accumulation of merit reciting purificatory mantras, making prostrations and offerings of the mandala many hundred thousand times. Tsongkhapa simultaneously continued to study the most important texts dealing with the nature of reality.

In 1394 he and the others moved to Wölka ('Ol kha) and while they were there they all experienced visions of deities associated with the practices in which they were engaged. In 1395 they decided to break this retreat to refurbish and reconsecrate a famous and venerated statue of the future Buddha Maitreya which had fallen into disrepair. This generated much interest and many craftsmen and benefactors offered their help for the project, which was successfully completed.

For the next three years Tsongkhapa and his companions continued to practice in Lodrak (IHo brag) and then in 1397 they began a final year of retreat again in the Wölka area. In the late spring of 1398 these concerted and extraordinary efforts finally bore fruit. One night Tsongkhapa dreamed that he was present at a gathering of famous Indian masters discussing the subtleties of the Madhyamika view. One of them, who was dark-skinned and tall and whom Tsongkhapa recognized in the dream as Buddhapalita, rose and, holding a volume in his hands, approached Tsongkhapa and joyfully blessed him by touching his head with the book. Tsongkhapa woke as it was getting light and opened his own Tibetan translation of Buddhapalita's commentary at the page which he had been reading the day before. When he reread the passage he at once experienced a seminal insight into the nature of reality, which brought him the understanding that he had been seeking.

Among Tsongkhapa's many beneficial activities four are mentioned in particular. The first was the renovation of the statue of Maitreya and the subsequent great festival he organized during the Tibetan New Year in 1400 at Dzingji ('Dzingji) temple, which housed the statue. The second was an extensive teaching on the code of discipline for the ordained which he, Rendawa and Kyapchok Pel Zangpo (sKyabs mchog dPal bzang po) gave for several months at Namtse Deng (gNam rtse Ideng), thereby revitalizing the tradition of monasticism.

The third deed was his establishment of the Great Prayer Festival in Lhasa in 1409, beginning a tradition that has continued until now of devoting the first two weeks of the Tibetan new year, culminating on the day of the full moon, to prayers for universal well-being. Tsongkhapa donated everything he himself had received from benefactors to support this event and offered ornaments made of gold and precious stones to the famous statue of the Buddha in the main temple in Lhasa.

The fourth deed was the construction of Ganden Monastery (dGa' Idan) near Lhasa. "Ganden" means "The Joyous" and is the Tibetan name given to the pure land of Maitreya. The monastery was completed and consecrated in 1410. In 1415 special halls were built to house selected mandalas. Under Tsongkhapa's guidance skilled craftsmen created these mandalas and images of the relevant deities, which were installed in 1417. All of this was destroyed after the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1959.

During his last years Tsongkhapa devoted much of his energy to giving extensive teachings. He passed away in 1419. Personally and through his students he made an extremely significant impact on the development of Buddhism in Tibet and his influence extended to Mongolia and China. He wrote prolifically and lucidly on topics connected with both sutra and tantra, and thanks to his clear and elegant style these great works remain illuminating, relevant and accessible to this day.

[This biography was included in the Introduction of Geshe Sonam Rinchen's book The Three Principal Aspects of the Path.

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

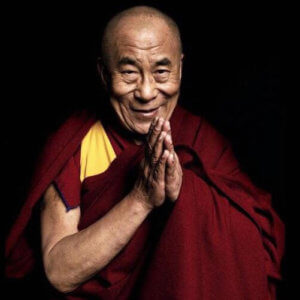

The Dalai Lama: Reliance on a Teacher

This article on reliance on a teacher originally appeared in the Snow Lion newsletter, Vol 12 #4, Fall 1997

Answers to Questions at the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center, Washington, New Jersey, September 1990

Joshua Cutler: Americans in general are very wary of relying on one person and giving that person a lot of power and control. This is difficult for American people. But on the other hand, I know that, when the teaching was coming from India to Tibet, Atisha was asked by Dromtonpa, "How is it that we Tibetans have such a good knowledge of the teachings yet no one has produced any of the realizations of the grounds and the paths?" Atisha replied that it was because Tibetans were still viewing the teacher as an ordinary person. It’s very clear to me that this teaching of faith in the spiritual teacher is the very foundation of the teaching being able to grow in this country, but there is a problem because many spiritual teachers have abused their students and so people are very suspicious of teachers. Could Your Holiness please give us guidance on this practice of relying upon the spiritual teacher?

Related Books

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

$19.95 - Paperback

By: Atisha & Geshe Sonam Rinchen & Ruth Sonam

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Atisha explicitly mentions that all the Great Vehicle realizations, be they great or small, depend on proper reliance upon a spiritual teacher. He then says that as the Tibetans view their lamas as only ordinary persons, they are not attaining realizations. His advice applies to Great Vehicle realizations.

But in giving a general explanation of Buddha’s doctrine, we have to include both the Great and Hearer Vehicles. Therefore, take for example the solitary realizers. In Maitreya’s Abhisamayalamkara, which is the root text of the lam rim lineage, he specifically mentions that solitary realizers achieve their liberation without relying on verbal guidance from another person. They attain their realizations mainly through their own introspective reflections. So we must make a distinction between general realizations and Great Vehicle realizations.

Therefore, it is in the practice of the Great Vehicle path, particularly in the practice of Great Vehicle’s tantric path, that reliance on spiritual guidance becomes indispensable. Why is this so? In my estimation, a general understanding of the framework of the Buddhist path that is common to both the Great and Hearer vehicles is something that we can develop quite clearly on our own by reading, introspective reflections, and so on. When practicing and developing the realizations of the Great Vehicle path, however, we cannot always take the Great Vehicle sutras literally. There are various levels of meaning—the literal, the interpretable, and the final meaning. There are also many differences when we consider the traditions of the different monasteries. For example, Buddha taught the selflessness of phenomena in the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, his definitive or principal teaching. The commentaries on his thought in these sutras differ in their explanation of emptiness. Therefore, in order to unravel the various intricacies in the meaning of these sutras, it is very helpful to hear the explanation of a qualified lama. Especially in the case of tantra, where there is special emphasis on using one’s afflictive emotions in the path, seeking proper guidance from someone who has actual and exact experience in this path is indispensable. Otherwise it is difficult for religious practice to be helpful. Rather, it will be only dangerous.

In the Great Vehicle literature, such as the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, there are two levels of meaning— the explicit teaching and the hidden meaning—whereas in the Hearer Vehicle sutras there is no such presentation of two levels of meaning. Therefore Maitreya called his Clear Ornament of Realization (Abhisamayalamkara) (which is a commentary on the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra) a "treatise of quintessential instructions," indicating that it contained instructions that would give us the keys to unlock the hidden meaning within the sutra. For this reason, in order to practice the Great Vehicle it is very important to rely on the spiritual teacher.

However, in the Hearer Vehicle as well, we do find sutras, such as the Sutra on Moral Discipline (Vinayasutra), in which there are instructions to rely first on the lama who teaches moral discipline, and then on other lamas who principally will show the path to liberation. Thus, doesn’t this indicate that the lama is very important?

Since reliance on a lama is a very important factor in spiritual practice, there are detailed presentations of the qualifications that are necessary for such teachers in both the Great Vehicle and Hearer Vehicle scriptures. The import of doing this is to emphasize the point that the spiritual teacher should be someone who will not mislead the students. Particularly, in tantric practice it is explained that the lama and disciple should examine each other for up to twelve years before adopting a teacher-disciple relationship.

Along with the description of the qualifications of the lama that is found in the literature on moral discipline, the question is raised of how to look for such qualities in a person who is a candidate for one’s spiritual teacher. In one of the moral discipline commentaries called The Commentary of Tso-na-wa, a reference to examining the lama can be found at the end of a section commenting on the passage in the Sutra on Moral Discipline which talks about the qualifications that are necessary for an ideal teacher. The author quotes a verse from sutra which says, "Although a fish is hidden below the water, it is revealed by the ripples on the surface." In the same way, we can understand a person’s mental qualities by examining his or her daily behavior, speech, and physical expressions.

For more on the Abhisamayalamkara and the other Five Maitreya Texts, see an interview with Karl Brunnholzl or see him discuss this below:

Also, in his Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lamrim Chenmo)Tsongkhapa presents the method for proper reliance upon the lama and lists the lama’s qualifications, particularly the ten qualifications of a Great Vehicle teacher. In this section Venerable Tsongkhapa responds to a passage from the teachings of Geshe Potawa, the Kadampa master, where the question is raised: "What if the person whom you are thinking of taking on as your spiritual teacher does not possess all these qualifications? What minimum qualifications should we seek in such a person?" Tsong-khapa gives the answer that the most important qualification is compassion for the students. As long as that person has this quality, even a single instruction that the teacher might give will be beneficial to the students. The other nine qualifications, such as skill, are necessary, but compassion is the principal quality required.

In this section Venerable Tsongkhapa also mentions nine attitudes that we must adopt when relating to our lama. To illustrate one of these attitudes, he says that we should behave like very obedient children behave toward their father. Whatever such children do, they always take into consideration the wishes of their father, and totally give themselves over to their father’s control. (This example reflects the way people thought at a certain time in India, not necessarily in today’s America.) Having said that, Venerable Tsongkhapa makes the very significant point that this analogy is made from the viewpoint of how we must relate to a fully qualified lama. He says that it is therefore very important to bear in mind that we should not simply be "led by the nose" by just anyone. In Tibetan these words are very powerful. There is a Tibetan saying that we should not allow just anyone to take the rope which is tied to our nose. This expression might have come from the Tibetan custom of tying a rope through the nose of yaks and other animals to enable the owner to lead the animal anywhere. So Venerable Tsongkhapa’s point is that we should not let just anyone have authority over us. I always refer to this quotation because it is very clear.

Furthermore Venerable Tsongkhapa substantiates his point with a quote from sutra which states, "Act in accord with that which is virtuous; do not accord with that which is not," Then in response to the question, "Is that'only in the case of the sutra path?" Venerable Tsongkhapa answers that it is the same for the tantric path as well, and supports this by citing the following quotation from the Fifty Verses of Guru Devotion, "If we find that [an instruction] is not proper through reasoning, we should say something in reply."

After Venerable Tsongkhapa gives the quote from the Cloud of Jewels Sutra, he mentions that "the meaning of not engaging in that which is improper is clarified in the Twelve Buddha Birth Stories.'' According to the birth story to which Venerable Tsongkhapa refers, Buddha was once born as a brahmin in India. One day his teacher decided to test some of his students, and summoned them to him. He said, "Nowadays I’m having very serious financial problems. Therefore you students should think about my situation."

The students replied, "Now that you are in such difficulty, we will do whatever you ask us to do."

The teacher said, "I should say something to you but you won’t do what I say."

They all protested, "We will certainly do it."

The teacher then said, "It is said, ‘When a brahmin is declining in his fortune, it is virtuous to steal.’ Brahma, the creator of the universe, is the father of all brahmins. When a brahmin is declining in fortune, it is all right to steal, because everything is Brahma’s creation, and the brahmins own those creations. Thus it is said, ‘When a brahmin is declining in his fortune, it is virtuous to steal.’ Therefore, please go and steal something."

Most of the students replied that they would do just as the teacher said, but the student who was to become Shakyamuni Buddha remained silent.

The teacher asked him, "You are my student. When I have such difficulty, why are you not saying anything?"

The student said, "You, my teacher, have instructed us to steal, but according to the general teachings stealing is completely improper. Although you have said to do it, it doesn’t seem right."

The teacher was very pleased and said, "I said this in order to test you all. He is the one who has actually understood my teaching. He has not been led foolishly anywhere like the front of a rivulet of water, but has examined what his teacher has said, and made his own determination. He is the best among my students."

Therefore, if we have understood well the complete approach to the path in the Great Vehicle scriptures, there will be no problems. But the lama also has to be cautious. Therefore as a concluding remark, after mentioning the qualifications of the lama in this section on proper reliance on the spiritual teacher, Venerable Tsongkhapa says that those who wish to seek students and become teachers must examine whether they have all these qualifications, and then achieve those that they lack. Similarly the students who wish to seek a lama must also examine whether the potential lama has these qualifications, and rely on a lama who has them. Otherwise, if the student is ignorant of these factors and then comes into contact with a teacher who is also very presumptuous and greedy, both are put in a very difficult position.

At the end of the section on special insight in the Great Exposition, Venerable Tsongkhapa mentions that if disciples have strong faith but do not have intelligence, they can be led foolishly anywhere, just like the front of a rivulet of water. They will do whatever they are told. We should not be like this.

We should understand these points. So, I think it is very important to make people aware of these points by writing articles in papers, journals, and so on, especially when you know that there is some danger to the integrity of the teachings because of cases where people have taken on the role of teacher and then exploited the trust of their students.

Do you have any further questions regarding this point?

Vikki Urubshurow: In the biography of the famous Naropa there are many seemingly unethical acts. Why is this such an important text?

His Holiness: I always say that if it is a case of the teacher being as highly qualified as Tilopa, and the student being as highly qualified as Naropa, then it is completely exceptional. However, it is very difficult to find a teacher who has such high qualifications as Tilopa and also very difficult to find a student who has the qualifications of Naropa.

There is a Tibetan saying that states, "If the fox tries to jump where the lion can jump, the fox will break its spine."

When teachers give instructions on how to practice proper reliance on the spiritual teacher, they emphasize different points of the practice. Some teachers assume that the teacher and the student have the complete qualifications, and stress following such good examples of the teacher-disciple relationship as those of Naropa and Tilopa, Milarepa and Marpa Lotsawa, and Shon-nu-nor-sang and his teacher. Nowadays, it is a time of unfavorable conditions. Therefore, Venerable Tsongkhapa’s approach is more well-balanced. This is very important to understand.

It is dangerous to assume that you can give instructions on the practice of faith and the use of pure perception (dog snang). Rather it is better that both the teacher and disciple examine one another, using analysis just as we do when studying the philosophical texts. Isn’t this approach much more reliable?

More on the student-teacher relationship:

The Teacher-Student Relationship

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye & Ron Garry & Ven. Gyatrul Rinpoche & Lama Tharchin

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is considered the foremost Buddhist leader of our time. The exiled spiritual head of the Tibetan people, he is a Nobel Peace Laureate, a Congressional Gold Medal recipient, and a remarkable teacher and scholar who has authored over one hundred books.

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is considered the foremost Buddhist leader of our time. The exiled spiritual head of the Tibetan people, he is a Nobel Peace Laureate, a Congressional Gold Medal recipient, and a remarkable teacher and scholar who has authored over one hundred books.

Books by H.H. The Dalai Lama

How Karma Works: The Twelve Links of Dependent Arising

An Oral Teaching by Geshe Sonam Rinchen

We all want to find happiness and be free from suffering. The twelve-part process of dependent arising shows how actions underlain by ignorance propel us from one rebirth into another, keeping us trapped in suffering, and how through understanding reality correctly we can break this cycle. The following three excerpts from How Karma Works by Geshe Sonam Rinchen, a well-known teacher in Dharamsala, are based on the Rice Seedling Sutra and the twenty-sixth chapter of Nagarjuna’s Treatise on the Middle Way.

Conditioned by formative action,

Consciousness enters rebirths.

When consciousness has entered,

Name and form come into being.

A variety of causes and conditions produce each moment of consciousness, but here Nagarjuna emphasizes how formative action determines which kind of rebirth the consciousness will enter. How does consciousness continue on? It does so when the death process is complete and the moment of death occurs. This is simultaneous with the beginning of the intermediate state. In the case of a human rebirth, the being of the intermediate state ceases to exist at the moment when consciousness enters the fertilized ovum in the womb of the mother. The end of the intermediate existence and the beginning of the human existence are simultaneous. The final moment of the death process is like deep sleep; the intermediate state is like dreaming and conception like waking.

The fourth link, name and form, describes the moment of conception. “Name” refers to the four aggregates of feeling, discrimination, compositional factors, and consciousness, while “form” refers to the physical embryo. The entity of the being has come into existence, after which development takes place.

Just as barley seed or rice seed yield their own specific crop, the imprints implanted on consciousness through performing actions yield their own particular results in the form of good or bad rebirths. When rebirth in the desire realm or form realm occurs, all five aggregates are present from the very beginning. In the formless realm the four aggregates associated with mental activity are present, but since beings in that realm have no actual physical form, the physical aspect is present only as a potential.

∗ ∗ ∗

Experience and Response

The next verses of Nagarjuna’s text show how the capacity to experience arises and how response to experience takes place while the unborn child is growing.

When name and form have come into being,

The six sources emerge.

In dependence on these six sources

Contact properly arises.

Gradually the fetus develops and the six sources—from the eye sense faculty to the mental faculty—are formed. The bases for these faculties are there from the outset, but this link is called the six sources because now the sources have developed and can function. The mental faculty and mental consciousness in a subtle form are present from the moment of conception.

At conception the entity of the living being came into existence. The attributes of that living being emerge with the development of the six sources and it now becomes a user of things, namely one who can engage with things. All of this is the maturation of an action performed in the past.

What are the conditions that give rise to contact? In the third verse Nagarjuna underlines the vital role played by the faculties when he writes, “In dependence on these six sources contact properly arises.”

∗ ∗ ∗

A Gift for a King

During the Buddha’s lifetime there was a king called Bimbisara who, it is said, struck up a relationship with another king called Utrayana. Utrayana lived in a rather remote place and, although the two kings had never met, messengers went back and forth between them. On one occasion King Utrayana sent King Bimbisara a very precious and special jewel. It had the power to give a feeling of well-being and to remove poison when touched.

Since the jewel was priceless, this gift proved quite an embarrassment to King Bimbisara, who felt obliged to send a gift of equal value. His ministers tried to estimate the value of the jewel, but when they calculated it in gold coins, it turned out to be ten million. How could they reciprocate with a gift worth ten million gold coins? They could think of no solution. King Bimbisara was despondent and retired to a darkened room. He took off his normal finery and lay down on his bed. Seeing this, one of his ministers, who was a Brahmin, suggested to the king that he should consult the Buddha.

The Buddha’s advice was simple: he told Bimbisara to send King Utrayana a painting of himself, the Buddha. A number of painters were summoned and it was decided that the best painting would be chosen as the gift. Some versions of the story recount that when the painters saw the Buddha, they could not stop gazing at him and were quite unable to begin painting. This once again depressed King Bimbisara, but the Buddha solved the problem by using his radiance to project his image onto their canvases. Other accounts say that the Buddha’s radiance was so powerful that the painters were dazzled and could not paint him, so he told them to look at his reflection in a pool.

The best image was chosen and the Buddha instructed the painter to depict the twelve links of dependent arising around the edge of the painting. Some verses about this twelve-part process were written at the bottom. The painting was wrapped in many layers of costly silks and brocades. It was carefully placed in a golden box and dispatched to the king, but it was preceded by a letter to him.

The letter announced to King Utrayana that King Bimbisara was sending him a gift that transcended all other gifts in the world. In order to receive it properly he should prepare the road leading to his city and palace by having it cleaned for several miles, and that he and his retinue should welcome it with great ceremony and offerings.

When King Utrayana saw this letter, he felt irritated and insulted by its tone of command, and he remarked to his ministers that he would prepare his troops for battle. But the ministers, who were rather more circumspect and sensible, suggested that it might be a wiser policy first to see what the gift was and then, if it didn’t please the king, they could make ready for war. So preparations were made to receive the gift in the manner described by King Bimbisara.

They escorted it ceremonially into the palace. Then, with the whole court waiting in suspense, it was taken out of the golden box. To everyone’s surprise, when the many layers of silk and brocade had been removed, what lay before them was a rolled-up painting. Eagerly they unrolled it and found a beautiful portrait of someone they did not know. Present at court, however, were some merchants who had visited Magadha, the area where Bimbisara lived, and they recognized that it was a painting of the Buddha. At once they began speaking words in praise of the Buddha and paid homage to him. King Utrayana and his court had already been prepared for something exceptional. Moved by the image and by the reverence of the merchants, they were quite overcome.

Through the arrival of this gift past positive imprints were awakened in the king and his court. The king took the painting to his private quarters. That evening he looked carefully at the twelve images around the edge and read the verses. Throughout the night he thought very deeply about this whole twelve-part process in forward and reverse sequence, and in the course of this intensive meditation he reached the stage of a stream enterer, that is, he had direct perception of the truth. It is said that even just seeing these twelve links depicted creates beneficial imprints, so thinking about them again and again with understanding of how they function will undoubtedly have a very profound effect and bring vast benefit.

The King of Meditative Stabilizations Sutra says that even if we look at the image of a Buddha when we are angry, negativity created over many aeons is purified. If that is true, we can easily imagine how much negativity is purified and how much virtue created when we look at such an image with faith in our hearts, make a gesture of homage as an expression of that faith and speak words of praise. The four noble truths, the twelve links of dependent arising and the two truths regarding conventional and ultimate reality, all interrelated, form the very core of the Buddha’s teaching. The many different practices of sutra and tantra become meaningful and purposeful only when they are based on a good understanding of these fundamental and seminal principles.

More Books by Geshe Sonam Rinchen

The Heart Sutra: An Oral Teaching by Geshe Sonam Rinchen

| The following article is from the Autumn, 2003 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

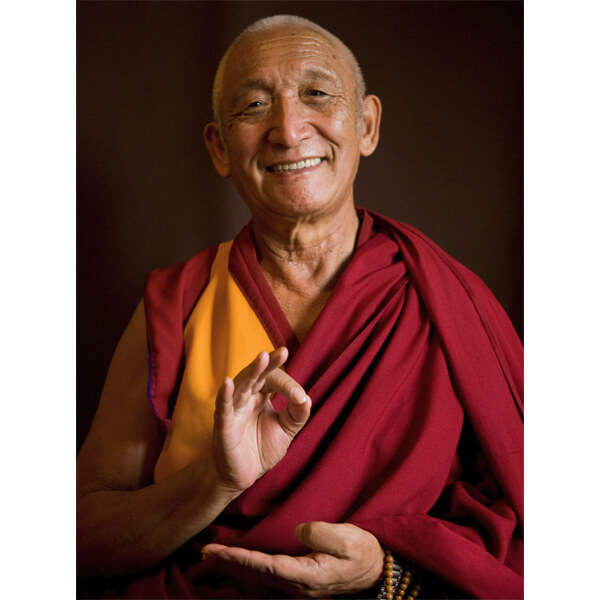

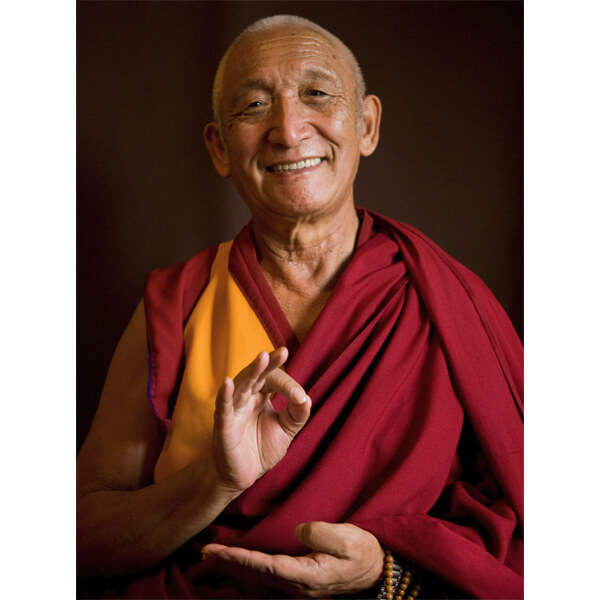

Photo by Peter Aronson

This short gem of a book shows how distorted perceptions and disturbing emotions―arising from our misunderstanding of reality―can be completely uprooted, resulting in a freedom from suffering. Understanding the nature of reality is the key to liberation. The wonderfully concise Heart Sutra is considered the essence of the Buddhas' teachings.

The author's long experience in teaching Western students at the Dalai Lama's Library of Tibetan Works and Archives makes The Heart Sutra an ideal introduction for Westerners to this important subject.

A short excerpt from a chapter of the The Heart Sutra titled The Mantra follows.

Therefore, the mantra of the perfection of wisdom is a mantra of great knowledge. It is an unsurpassable mantra, a mantra comparable to the incomparable. It is a mantra that totally pacifies all suffering. It will not deceive you, therefore know that it is true! I proclaim the mantra of the perfection of wisdom: DAY AT A (OM) GATE GATE PARAGATE PARASAMGATE BODHI SWAH A.

Because the Heart Sutra contains a mantra there has been extensive discussion by the commentators about whether it should be classified as a sutra teaching or as a teaching of secret mantra. In both sutra and tantra the final object is the same to attain the body, speech, and mind of an enlightened being. Although the complete path to enlightenment is laid out from a sutra point of view in the Heart Sutra, the introduction of the mantra indicates that when the essential realizations have been gained, it is necessary to engage in tantric practice in order to attain enlightenment. Tendar Lharampa states that it is difficult to decide how the Heart Sutra should be classified, while Gungtang Jampelyang says it should be considered as a sutra teaching because the practice of secret mantra is merely indicated.

A mantra is that which protects the mind. Through this mantra, which is the perfection of wisdom itself, we can overcome the demon of ignorance that possesses us and find unsurpassable happiness. It protects the minds of those who practice it from all fears and describes how to make the transition from worldly existence to the supreme state beyond sorrow. It is a mantra of great knowledge because it saves us from the poison of ignorance and its imprints. It is an unsurpassable mantra because it frees us from suffering and its causes as no other path of insight can. The incomparable is the state beyond suffering. Since it helps us to attain that state, it is comparable to the incomparable. It totally pacifies suffering because it rids us of all the troubles of the world and their causes. The world here refers to ordinary beings like us. Our troubles are many but foremost are birth, aging, sickness, and death. This mantra does not deceive us and it is true because wisdom sees things as they actually are without any error or deception. It is therefore transcendent.

A mantra is that which protects the mind. Through this mantra, which is the perfection of wisdom itself, we can overcome the demon of ignorance that possesses us and find unsurpassable happiness.

This description of the mantra also sets out the five paths. Thus the mantra of the perfection of wisdom refers to the path of accumulation; a mantra of great knowledge to the path of preparation; an unsurpassable mantra to the path of seeing; a mantra comparable to the incomparable to the path of meditation; and a mantra that totally pacifies all suffering to the path of no more learning. When we have actualized these five paths, we are totally protected.

Eight Verses For Training the Mind

| The following article is from the Summer, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Geshe Sonam Rinchen

How do we free ourselves from the demon of self-concem? These instructions are found in Eight Verses for Training the Mind, one of the most important texts from a genre of Tibetan spiritual writings known as lojong (literally "mind training''). The root text was written by the eleventh-century meditator Langri- tangpa. His Holiness the Dalai Lama refers to this work as one of the main sources of his own inspiration and includes it in his daily meditations.

"Among the many brilliant texts that the collaboration of Geshe Sonam Rinchen and Ruth Sonam have produced, this one explains in clear terms how to implement the essential practices of compassion, which are so difficult to integrate into one's daily life. What a treasure!"—JEFFREY HOPKINS

"As a student of Geshe Sonam Rinchen, I can almost see his bright smile and hear his compassionate voice as I read this book. His practical and clear spiritual advice cuts to the core of our problems and shows us the way to resolve them."—BHIKSHUNI THUBTEN CHODRON

"Once more Geshe Sonam Rinchen has presented us with the authentic tradition of Tibetan Buddhism in this clear explanation of one of its most basic texts. I recommend it highly to all who wish to overcome the depression of self-pity through the development of deep concern for others."—ALEXANDER BERZIN, author

"Geshe Sonam Rinchen has masterfully invoked the full force of a traditional commentary to this classic mind training text that will challenge anyone sincere about confronting their egoism and transforming it into altruism."—TUBTEN PENDE, Director of Education, FPMT Buddhist Centers

Geshe Sonam Rinchen is resident scholar at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala, India, where he teaches Buddhist philosophy and practice.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter titled "The Treasure Trove."

Geshe Langritangpa suggests another way of dealing with provocative situations that cause the disturbing emotions to arise. In our normal everyday life we cannot avoid meeting people who are very difficult. When trying to forget about ourselves and cherish others, the kind of seclusion that we must seek in such situations is not to isolate ourselves physically but to distance ourselves from self-concern and self-interest.

When I see ill-natured people,

Overwhelmed by wrongdoing and pain,

May I cherish them as something rare,

As though I had found a treasure-trove.

When faced with ill-natured people, we should think about the fact that in the past they failed to see the harmfulness of the disturbing emotions which now overwhelm them. They became accustomed to giving them full rein and this familiarity has carried over into their present life. Nor can they have created much positive energy. All of this accounts for their unpleasant conduct.

There are so many people who are ungrateful for the kindness which others show them. Imagine you have cooked a delicious meal for a sick friend and you bring it to her. In her haste to eat she takes a big mouthful and burns her tongue. Angrily she pushes the plate away or worse still throws it on the ground. Such bad manners, so ungrateful! Our normal reaction would be to feel angered and swear never to do anything for her again. Many people indulge their disturbing emotions and do nothing to curb them. They don't see anything wrong with expressing them. It is as if they are running around stark naked, without the clothing of self- respect and decency.

There are people who commit horrifying ill-deeds, such as the five extremely grave and the five almost as grave negative actions. There are others who have broken their ordination vow as a monk or nun but still shamelessly make private use of what belongs to the spiritual community. This has always been considered very wrong. In a secular context, a similarly serious action would be to appropriate monetary donations or things given to an aid organization and use them for private purposes.

Then there are those suffering intensely from deforming, incurable or contagious diseases, just hearing the name of which makes us feel afraid. When we are faced with these three categories of people, we should not try to avoid or ignore them, pretend we haven't seen them or turn our backs on them. Instead of rejecting them and keeping as far away as possible out of fear or disgust, which we instinctively do, we should regard them with a sense of closeness and compassionately help them in whatever ways we can.

In the case of those who are doing wrong, we must consider what the consequences of their wrong actions will be and feel as sorry for them as we would for a man who has been condemned to death and who is being led to his execution. Concerning those who are sick, we should remember that their suffering is the consequence of past negative actions and a lack of merit. There is no knowing whether the momentum of those actions will come to an end in this life or whether they will have to endure further suffering in the future. To all of these unfortunate people we should speak kindly and compassionately and try to be helpful in stopping them from doing anything negative. If our advice falls on deaf ears, we shouldn't feel discouraged, but without harshness and without losing our kindheartedness we should continue to do what we can to prevent them causing further harm.

Others' stubbornness can be discouraging and exhausting. Our involvement with them seems to harm us and we would definitely prefer to have nothing further to do with them. The masters of this mind-training tradition urge us to avoid such thoughts at all costs, remembering how easily we could be in their place. Without being condescending, we should give practical help and in imagination take on their suffering with the wish that it should ripen on us.

People who are difficult to deal with offer us a precious chance to train ourselves to be loving, compassionate and altruistic, generous, ethical and patient. That is why they are like a precious treasure. A true practitioner feels responsible for steering them in a positive direction.

Shantideva says:

The beggars in this world are many,

Attackers are comparatively few.

For as I do no harm to others,

Those who do me injury are rare.

Ill-natured and hostile people allow us to practice the patience of willingly accepting difficulties and of taking no account of those who harm us. For this reason it is right to feel delighted when we come across them and to remember their kindness since, unintentionally, they help us along the path to enlightenment.

In fact we do not meet such challenges very often. If we knew there was treasure underground or on a ship that has sunk, we would go to enormous trouble to bring it up to the surface and would certainly take great care of our find. Encountering people who challenge us in these ways is like finding such a treasure. We should be prepared to invest time and energy because through our contact with them we can increase our capacity to be compassionate. This will eventually lead us to the spirit of enlightenment and all the ensuing benefits.

If we are constantly surrounded by nice people who treat us well and by those who are in good health, we will lack the opportunity to increase our compassion. Therefore, when such a rare opportunity presents itself, we must recognize its value and cherish it. In this way we use adverse circumstances to support our spiritual practice, which is a central theme of the instructions for training the mind.

Practitioners who are already quite accomplished may well find there are relatively few people in relation to whom they can practice patience because they are less easily irritated, but most of us find that there are a lot of annoying people around. The more self-preoccupied and egocentric we are, the more enemies we think we have because anything others do that does not accord with our opinions and views is considered an act of hostility. Even a small unintentional gesture is interpreted as a snub and everything that happens is evaluated only from our narrow egocentric perspective. This can make us feel quite paranoid. One thing is certain, however: if even the great Bodhisattvas manage to find enough people who give them the opportunity to practice patience, we ourselves will certainly come across many more.