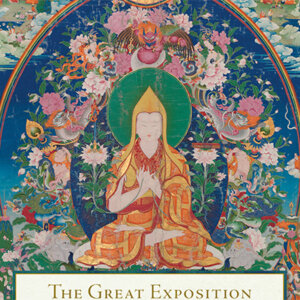

Tsongkhapa

Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), founder of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, was one of Tibet’s greatest philosophers and a prolific writer. His most famous work, The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path, is a classic of Tibetan Buddhism.

Tsongkhapa

-

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 2$29.95- Paperback

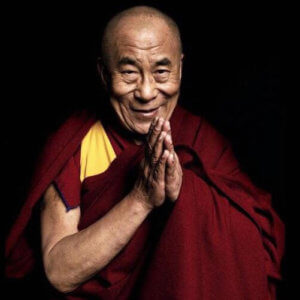

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 2$29.95- PaperbackBy H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Jeffrey Hopkins -

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 3$27.95- Paperback

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 3$27.95- PaperbackBy H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Jeffrey Hopkins -

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra

The Great Exposition of Secret MantraStarting at $27.95

By H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Tsongkhapa

Edited by Jeffrey Hopkins -

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 1$29.95- Paperback

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 1$29.95- PaperbackBy H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Edited by Jeffrey Hopkins

By Tsongkhapa -

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Volume 1)$34.95- Paperback

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Volume 1)$34.95- PaperbackBy Tsong-kha-pa

Edited by Joshua Cutler

Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

Edited by Guy Newland -

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Volume 2)$28.95- Paperback

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Volume 2)$28.95- PaperbackBy Tsong-kha-pa

Edited by Joshua Cutler

Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

Edited by Guy Newland -

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Volume 3)$34.95- Paperback

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Volume 3)$34.95- PaperbackBy Tsong-kha-pa

Edited by Joshua Cutler

Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

Edited by Guy Newland -

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment Collection

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment CollectionStarting at $28.95

By Tsongkhapa

-

The Six Yogas of Naropa$39.95- Paperback

The Six Yogas of Naropa$39.95- PaperbackBy Tsong-kha-pa

Edited by Glenn H. Mullin

Translated by Glenn H. Mullin -

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment: Volume Three$39.95- Hardcover

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment: Volume Three$39.95- HardcoverBy Tsong-kha-pa

Edited by Joshua Cutler

Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

Edited by Guy Newland

GUIDES

Naropa: A Reader's Guide to the Great Master of Mahamudra

The following short biography of Naropa is adapted from Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism:

Naropa, Tilopa’s primary disciple, is born in wealthy circumstances, the favored son of a kshatriya (ruling caste in India) family. At seventeen, he is compelled by his parents to marry. After eight years of marriage, however, he announces his intention to renounce the world. He and his wife agree to a divorce, and Naropa, like Tilopa, takes ordination into the monastic way. Unlike Tilopa, however, Naropa invests many years in intensive study, mastering the major branches and varieties of Buddhist texts, including the Vinaya, Sutras, and Abhidharma of the Hinayana, the Prajnaparamita of the Mahayana, and the tantras. Eventually, he rises to the top of his religious profession, becoming first a high-ranking scholar at Nalanda and then its supreme abbot. His fame as a scholar spreads everywhere, and he is considered unexcelled in his understanding of Buddhist doctrine.

At Nalanda, he has an extraordinary experience with a seeming ordinary old woman but one who it turns out has a profound effect on his life and sends him to find Tilopa.

At this moment, Tilopa appears, a blue-black man dressed in cotton trousers, with a topknot and bulging bloodshot eyes. He declares that ever since Naropa formed the intention to seek him, Tilopa has not been separate from him and that it was only Naropa’s defilements that blinded him to this fact. He tells Naropa that he is a worthy vessel, will indeed be able to receive the deepest teachings, and that he will accept him as a disciple.

For the next twelve years, Naropa is Tilopa’s disciple, undergoing a most demanding tutelage. He suffers immensely through all kinds of physical, psychological, and spiritual trials, torments, and tribulations. The rigor of his training is in direct measure, he understands, to the karmic accretions and obscurations that he has accumulated in his previous lives. Each of Tilopa’s teachings is a catastrophe for Naropa’s sense of personal identity, and in each instance he believes himself to have been irreparably and mortally harmed. In each case Tilopa reveals a deeper level of Naropa’s being, one that is open, clear, and resplendent, independent of the life and death of ego. Throughout this period, Tilopa says very little, and Naropa’s instruction occurs in nonverbal ways, through his own pain and through symbolic gestures that he must assimilate. No security and certainly no confirmation are ever given, and Naropa is able to persevere out of complete devotion to Tilopa and his conviction that he has no other options.

After twelve years of training, one day Naropa is standing with Tilopa on a barren plain. Tilopa remarks that the time has now come for him to offer Naropa the much-sought-after oral instructions, the transmission of dharma. When Tilopa demands an offering, Naropa, who has nothing, offers his own fingers and blood. As Lama Taranatha recounts the event.

Then Tilopa, having collected the fingers of Naropa, hit him in the face with a dirty sandal and Naropa instantly lost consciousness. When he regained consciousness, he directly perceived the ultimate truth, the suchness of all reality, and his fingers were restored. He was now granted the complete primary and subsidiary oral instructions. Thereupon, Naropa became a lord of yogins.

From Tilopa, Naropa receives the transmissions of mahamudra, the six inner yogas, and the anuttara-yoga tantras, and himself becomes a realized siddha in the tradition of his master. Naropa is subsequently seen sometimes roaming through the jungles, sometimes defeating heretics, sometimes in male-female aspect (that is, in union with his consort, a mark of his realization), hunting deer with a pack of hounds, at other times performing magical feats, at still other times acting like a small child, playing, laughing, and weeping. As a realized master, he accepts disciples, and through all of his activities, however benign or unconventional and shocking they may be, he reveals the awakened state beyond thought, imbued with wisdom, compassion, and power. He is also a prolific author whose previous scholarly training enables him to be an eloquent writer on Vajrayana topics, evidenced by his works surviving in the Tenjur.

Naropa is a pivotal figure in the evolution of the Kagyu¨ lineage for the way in which he joins tantric practice and more traditional scholarship, unreasoning devotion and the rationality of intellect. Through him, Tilopa’s profound and untamed lineage is brought out of the jungles of east India and given a form which the Tibetan householder Marpa can receive.

Essential Texts by and about Naropa

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

Naropa's Wisdom: His Life and Teachings on Mahamudra

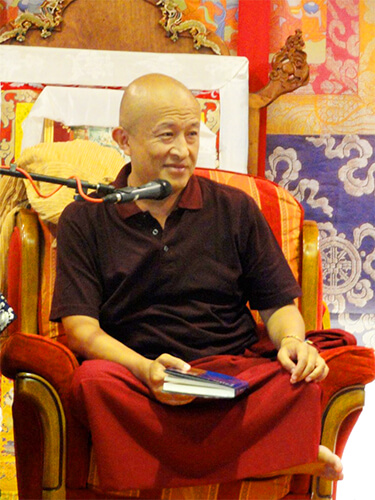

As the disciple of Tilopa and the guru of Marpa the Translator, Naropa is one of the accomplished lineage holders of the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. He expressed his realization in the form of spiritual songs, pithy yet beautiful poems that he sung spontaneously. In this book, Khenchen Thrangu, a contemporary Karma Kagyu master, first tells the story of Naropa’s life and explains the lessons we can learn from it and then provides verse-by-verse commentary on two of his songs. Both songs contain precious instructions on Mahamudra, the direct experience of the nature of one's mind, which in this tradition is the primary means to realize ultimate reality and thus attain buddhahood.

Thrangu Rinpoche’s teaching on the first song, The View, Concisely Put, explains the view of Mahamudra in a manner suitable for Western students who are new to the subject. The second song, The Summary of Mahamudra, contains all the key points of the view, meditation, conduct, and fruition of Mahamudra. Thrangu Rinpoche speaks plainly, directly, and without using any technical jargon to Westerners eager to learn the fundamentals of the Mahamudra path to enlightenment from a recognized master. As Thrangu Rinpoche says, “Mahamudra is a practice that can be done by anyone. It is an approach that engulfs any practitioner with tremendous blessings that make it very effective and easy to implement. This is especially true in our present time and especially true for Westerners because in the West there are very few obstacles in the practice of Mahamudra.”

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

Illusion's Game: The Life and Teaching of Naropa

In what he calls a "200 percent potent" teaching, Chögyam Trungpa reveals how the spiritual path is a raw and rugged "unlearning" process that draws us away from the comfort of conventional expectations and conceptual attitudes toward a naked encounter with reality. The tantric paradigm for this process is the story of the Indian master Naropa (1016–1100), who is among the enlightened teachers of the Kagyu lineage of the Tibetan Buddhism. Naropa was the leading scholar at Nalanda, the Buddhist monastic university, when he embarked upon the lonely and arduous path to enlightenment. After a series of daunting trials, he was prepared to receive the direct transmission of the awakened state of mind from his guru, Tilopa. Teachings that he received, including those known as the six doctrines of Naropa, have been passed down in the lineages of Tibetan Buddhism for a millennium.

Trungpa Rinpoche's commentary shows the relevance of Naropa's extraordinary journey for today's practitioners who seek to follow the spiritual path. Naropa's story makes it possible to delineate in very concrete terms the various levels of spiritual development that lead to the student's readiness to meet the teacher's mind. Trungpa thus opens to Western students of Buddhism the path of devotion and surrender to the guru as the embodiment and representative of reality.

Paperback | Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

The Life and Teaching of Naropa

Translated by Herbert V. Guenther

In the history of Tibetan Buddhism, the eleventh-century Indian mystic Nâropa occupies an unusual position, for his life and teachings mark both the end of a long tradition and the beginning of a new and rich era in Buddhist thought. Nâropa's biography, translated by the world-renowned Buddhist scholar Herbert V. Guenther from hitherto unknown sources, describes with great psychological insight the spiritual development of this scholar-saint. It is unique in that it also contains a detailed analysis of his teaching that has been authoritative for the whole of Tantric Buddhism.

This modern translation is accompanied by a commentary that relates Buddhist concepts to Western analytic philosophy, psychiatry, and depth psychology, thereby illuminating the significance of Tantra and Tantrism for our own time. Yet above all, it is the story of an individual whose years of endless toil and perseverance on the Buddhist path will serve as an inspiration to anyone who aspires to spiritual practice.

The Six Yogas of Naropa

The Six Yogas of Naropa

The Six Yogas of Naropa are a set of advanced tantric practices that can only be undertaken under the close guidance of a qualified teacher. We do not recommend these books unless one is under such guidance as misunderstanding is very likely.

Paperback | Ebook

$27.95 - Paperback

The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa

Edited by Glenn Mullin

This book on the Six Yogas contains important texts on this esoteric doctrine, including original Indian works by Tilopa and Naropa and writings by great Tibetan lamas. It contains an important practice manual on the Six Yogas as well as other works that discuss the practices, their context, and the historical continuity of this most important tradition.

- The Oral Instruction of the Six Yogas by Tilopa

- Vajra Verses of the Whispered Tradition by Naropa

- Notes on "A Book of Three Inspirations" by Je Sherab Gyatso

- Handprints of the Profound Path of the Six Yogas of Naropa by Gyalwa Wensapa

- A Practice Manual on the Six Yogas of Naropa by Tsongkhapa

- The Golden Key: A Profound Guide to the Six Yogas of Naropa by the First Panchen Lama

Paperback | Ebook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Six Yogas of Naropa: Tsongkhapa's Commentary

By Tsongkhapa, translated and introduced by Glenn Mullin

Tsongkhapa's commentary entitled A Book of Three Inspirations: A Treatise on the Stages of Training in the Profound Path of Naro's Six Dharmas is commonly referred to as The Three Inspirations. Anyone who has read more than a few books on Tibetan Buddhism will have encountered references to the Six Yogas of Naropa, a preeminent yogic technology system. The six practices—inner heat, illusory body, clear light, consciousness transference, forceful projection, and bardo yoga—gradually came to pervade thousands of monasteries, nunneries, and hermitages throughout Central Asia over the past five and a half centuries.

More Books Featuring Naropa

Paperback | Ebook

$27.95 - Paperback

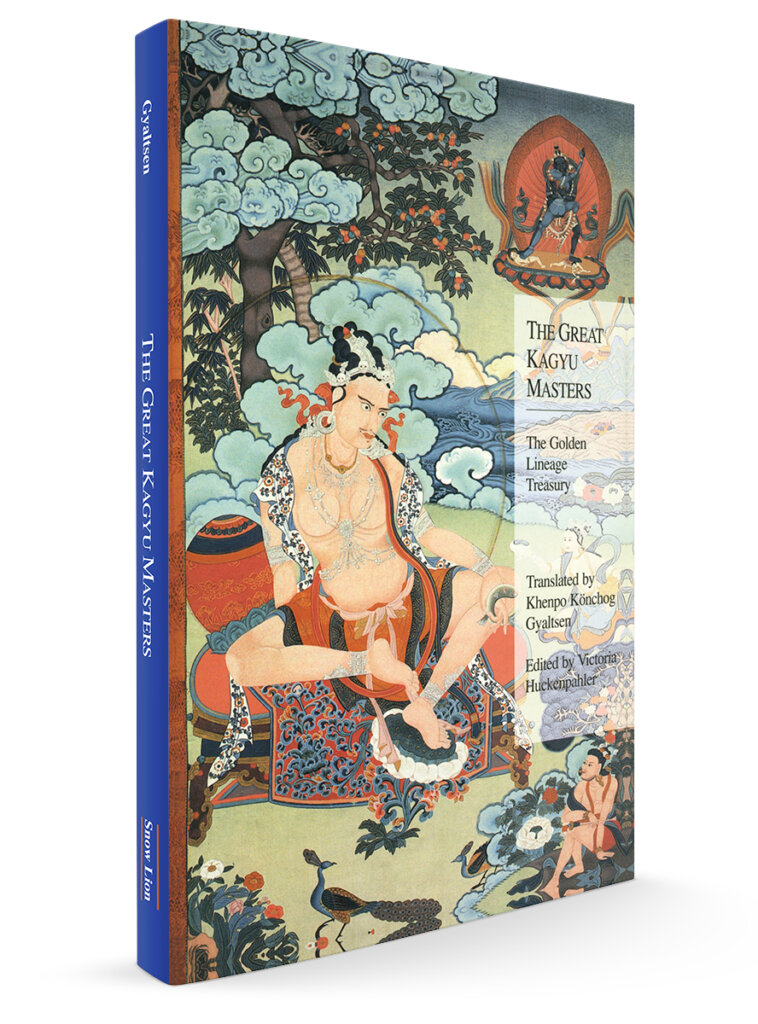

The Great Kagyu Masters: The Golden Lineage Treasury

Compiled by Dorje Dze Öd, translated by Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche

The Golden Lineage Treasury was compiled by Dorje Dze Öd a great master of the Drikung lineage active in the Mount Kailasjh region of Western Tibet. This text of the Kagyu tradition profiles and the forefathers of the tradition including Vajradhara, the Buddha, Tilopa, Naropa, the Four Great Dharma Kings of Tibet, Marpa, Milarepa, Atisha, Gampopa, Phagmodrupa, Jigten Sumgon, and more.

The chapter on Naropa is 45 pages long.

Hardcover | Ebook

$49.95 - Hardcover

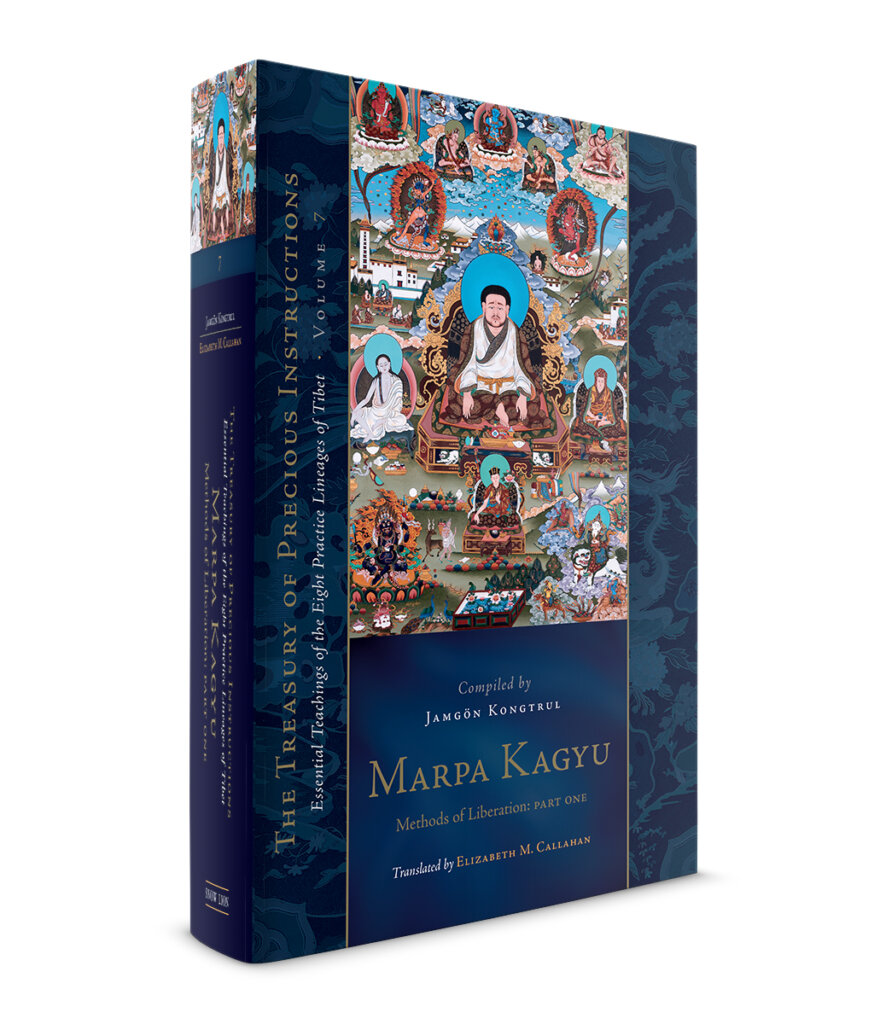

Marpa Kagyu, Part One - Methods of Liberation: Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 7

The Treasury of Precious Instructions

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye

The seventh volume of the series, Marpa Kagyu, is the first of four volumes that present a selection of core instructions from the Marpa Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. This lineage is named for the eleventh-century Tibetan Marpa Chokyi Lodrö of Lhodrak who traveled to India to study the sutras and tantras with many scholar-siddhas, the foremost being Naropa and Maitripa. The first part of this volume contains source texts on mahamudra and the six dharmas by such famous masters as Saraha and Tilopa. The second part begins with a collection of sadhanas and abhisekas related to the Root Cakrasamvara Aural Transmissions, which are the means for maturing, or empowering, students. It is followed by the liberating instructions, first from the Rechung Aural Transmission. This section on instructions continues in the following three Marpa Kagyu volumes. Also included are lineage charts and detailed notes by translator Elizabeth M. Callahan.

The piece by Naropa in this volume include:

- Summary Verses on Mahāmudrā

- Authoritative Texts in Verse: Mahāsiddha Nāropa’s Cycle on the Six

Dharmas - Vajra Song Summarizing the Six Dharmas: The Scholar-Mahāsiddha

Nāropa’s Instructions to the Lord of Yogins Marpa

Hardcover | Ebook

$24.95 - Hardcover

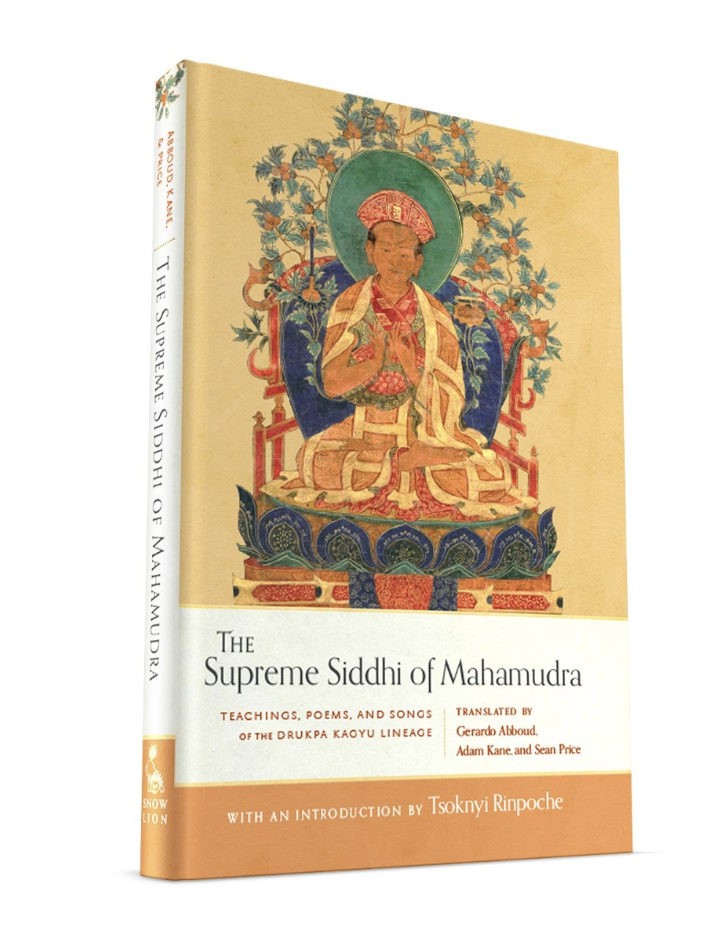

The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra: Teachings, Poems, and Songs of the Drukpa Kagyu Lineage

Translated by Gerardo Abboud, Sean Price, and Adam Kane

The Drukpa Kagyu lineage is renowned among the traditions of Vajrayana Buddhism for producing some of the greatest yogis from across the Himalayas. After spending many years in mountain retreats, these meditation masters displayed miraculous signs of spiritual accomplishment that have inspired generations of Buddhist practitioners. The teachings found here are sources of inspiration for any student wishing to genuinely connect with this tradition.

These translations include Mahamudra advice and songs of realization from major Tibetan Buddhist figures such as Gampopa, Tsangpa Gyare, Drukpa Kunleg, and Pema Karpo, as well as modern Drukpa masters such as Togden Shakya Shri and Adeu Rinpoche. This collection of direct pith instructions and meditation advice also includes an overview of the tradition by Tsoknyi Rinpoche.

The second chapter, on Naropa, is a translation of the Condensed Veses of Mahamudra, known in Sanskrit Mahāmudrāsaṃjñāsaṃhitā as and in Tibetan as (Chakgya Chenpo Tsig Dupa (Phyag rgya chen po’i tshig bsdus pa).

Combined with guidance from a qualified teacher, these teachings offer techniques for resting in the naturally pure and luminous state of our minds. As these masters make clear, through stabilizing the meditative experiences of bliss, clarity, and nonthought, we will be liberated from suffering in this very life and will therefore be able to benefit countless beings.

Translator on Gerardo Abboud on The Supreme Siddhi of Mahamudra

Hardcover | Ebook

$29.95 - Hardcover

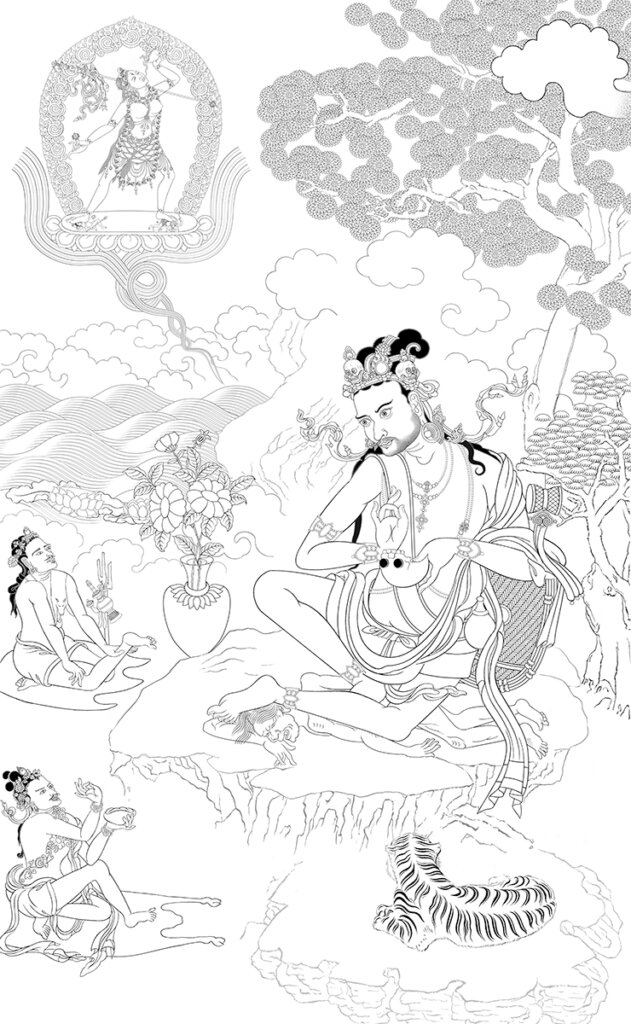

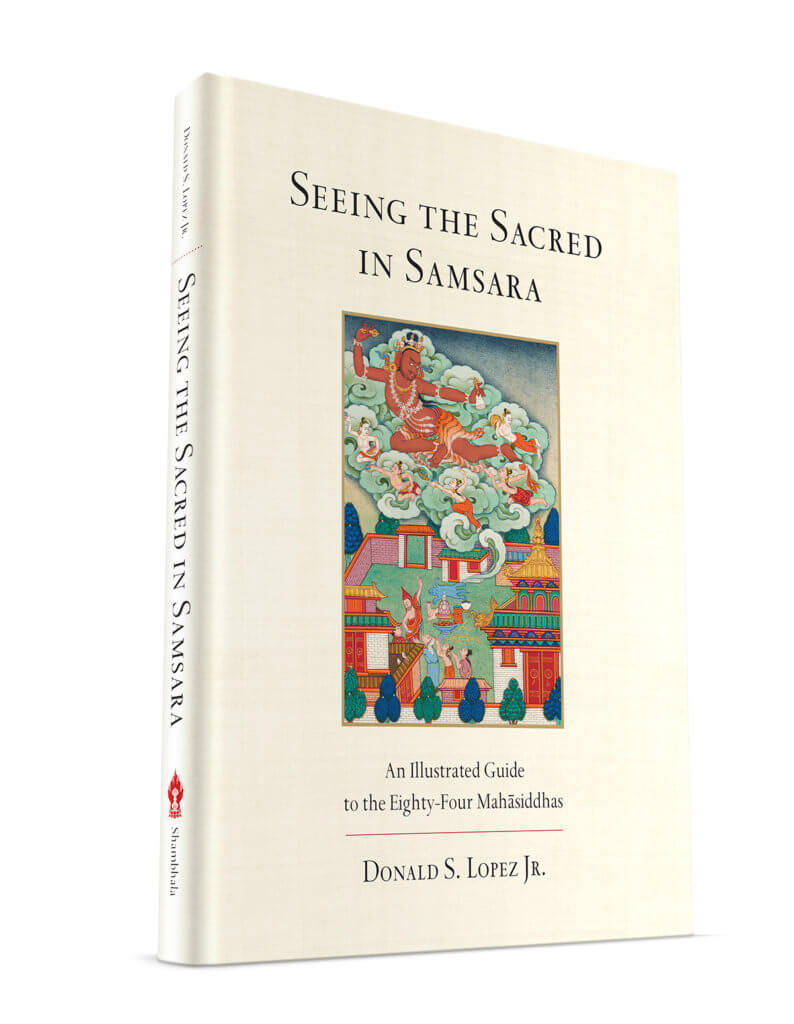

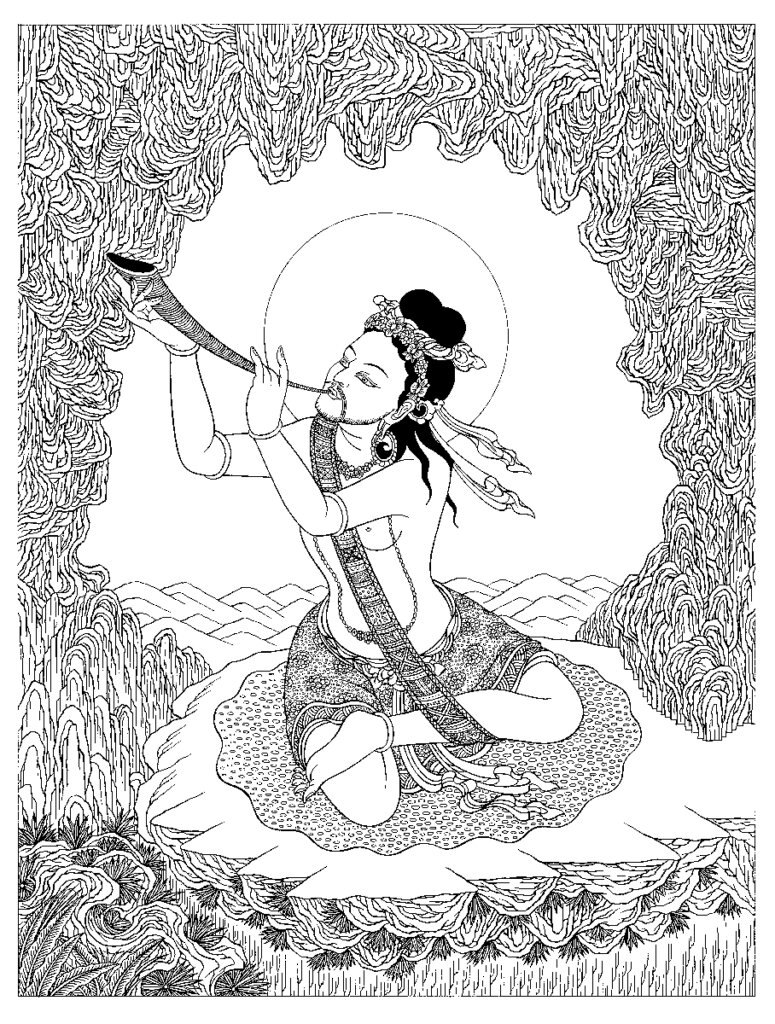

Seeing the Sacred in Samsara: An Illustrated Guide to the Eighty-Four Mahāsiddhas

By Donald S. Lopez Jr.

This exquisite full-color presentation of the lives of the eighty-four mahāsiddhas, or “great accomplished ones,” offers a fresh glimpse into the world of the famous tantric yogis of medieval India. The stories of these tantric saints have captured the imagination of Buddhists across Asia for nearly a millennium. Unlike monks and nuns who renounce the world, these saints sought the sacred in the midst of samsara. Some were simple peasants who meditated while doing manual labor. Others were kings and queens who traded the comfort and riches of the palace for the danger and transgression of the charnel ground. Still others were sinners—pimps, drunkards, gamblers, and hunters—who transformed their sins into sanctity.

This book includes striking depictions of each of the mahāsiddhas by a master Tibetan painter, whose work has been preserved in pristine condition. Published here for the first time in its entirety, this collection includes details of the painting elements along with the life stories of the tantric saints, making this one of the most comprehensive works available on the eighty-four mahāsiddhas.

The Naropa image from this book is pictured at the top of this page and explains what is being depicted.

Additional Resources on Tilopa

Lotsawa House hosts at least one work by Naropa as well as several where he features.

The Role of the Teacher in Tibetan Buddhism: A Reader's Guide to the Teacher-Student Relationship

To truly understand Tibetan Buddhism, one must come to grips with the unique role of the teacher, the dynamics of the teacher-student relationship, and the possibilities that having a teacher can open up.

Tibetan Buddhism is composed of the Vajrayana or Tantric teachings on top of a foundation of the Sutrayana (vehicle of the Sutras), the core teachings of what are sometimes called the Sravakayana and the Mahayana. In the context of the Sutrayana, a relationship with a teacher roughly maps to the categories of a pratimoksha master and a master of the bodhisattva vows, but there is a wide scope of possibilities and overlap within these roles. The teacher imparts, for example, important points on shamatha or vipashyana meditation, philosophy, or techniques like mind training (lojong), and these are akin to the role of teachers in other Buddhist traditions.

But in the relationship with a male or female vajra master in the context of tantric teachings, including Mahamudra and Dzogchen, the teacher and student have very specific commitments to each other, which is a very different situation. While this relationship may very well incorporate the elements of the relationship with a Sutrayana teacher, it is important for people to understand that a Vajrayana teacher is not really akin to the role of the Zen priest or the spiritual friend (kalyāṇamitta) of the Pali tradition of Buddhism, let alone the Hindu Guru, therapist, or a modern-day life coach. The practice of Guru Yoga (see sidebar below), whereby the student visualizes their teacher in the form of an enlightened being is one example of how different things are in this context. The relationship is much more central and is an essential mechanism for making great strides on the path.

That is why traditional texts encourage people to spend up to 12 years carefully considering whether a teacher of Vajrayana is suitable for them. They are not encouraging people to be wishy-washy and put off making a commitment; rather, this number underlines the importance of choosing a teacher very carefully.

The benefits are immeasurable and are not accessible without a teacher. The great 20th-century master Dudjom Rinpoche gives some traditional examples to demonstrate the importance:

Ordinary, childlike beings are incapable of proceeding even vaguely in the same direction as the perfect path by the strength of their own minds, so they need first to examine and then to follow a qualified diamond master. Diamond masters are the root that causes us to correctly engage in the whole Buddhadharma in general and especially to follow the path properly. They are knowledgeable and experienced guides for inexperienced travellers setting out on a journey, powerful escorts for those who are travelling to dangerous places, ferrymen steering the boat for people crossing a river. Without them, nothing is possible. This is reiterated in countless scriptures.

Recently, there has been a lot of news and discussion in the media, Buddhist and otherwise, around the role of the teacher in Buddhism—in particular, Tibetan Buddhism. This mostly relates to a small handful of teachers (including the leader of Shambhala International, an organization totally unaffiliated with Shambhala Publications) against whom there have been serious allegations of abuse of power, some of it sexual. Many of these articles have been read by a younger generation of Westerners curious about Buddhism and other spiritual traditions but suspicious of hierarchy, organized religion, and spiritual leaders with perceived authority. This media attention seems to validate their suspicions.

But however bad some of these cases are—and it should go without saying that someone who is causing harm is acting in complete opposition to the Buddhadharma—a teacher harming or taking advantage of a student is an unacceptable exception to the norm; it is a rare aberration in an incredible system that has benefited millions of people East and West in the most profound and transformative ways.

These aberrations are not new. People are human, and throughout Buddhist history (or any tradition) there has been the occasional charlatan or flawed leader—as the discussion of how to avoid a bad teacher in many of the texts below make plain. But the fact is that there are so many highly educated, spiritually accomplished (typically following many years in retreat), caring, selfless teachers in this tradition, and it is a shame that people who do not know better are being exposed, online and in print, only to the exceptions rather than the norm and the potential.

Specifically, much of the recent coverage and discussion online and in print around the role of the guru or lama has reflected a deep misunderstandings of the role of the teacher in Tibetan Buddhism and has therefore created a lot of confusion. The best way for a student to find the right teacher who can lead them far along the path to enlightenment is to have a solid ground in understanding what the roles are, to be aware of the cultural dynamics at play, and to know which qualities to seek and which to avoid.

So, we are pleased to share this Reader’s Guide to help those interested in understanding the role, importance, and centrality of the guru or lama and the transformative power of the student-teacher relationship. We hope this will better prepare those pursuing this path to understand the choices they are making and set them up for spiritual success and accomplishment.

Perhaps the book that addresses head-on the contemporary concerns and confusion about the role of the teacher—from gender inequality to power dynamics and bad apples—is Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s The Guru Drinks Bourbon. This is a thrilling modern guide to help students understand what they are in for and what is expected of them. It is, after all, a two-way street. He covers many areas and, while acknowledging a checklist is too simple of a model, he does present some helpful guidelines.

“The good guru

- has realized the ultimate view

- is open-minded

- is reluctant to teach

- is tolerant

- is learned

- is disciplined

- is kind and never denigrates others

- has a lineage

- is progressive

- is humble

- is not interested in your wallet, thighs, or toes

- has a living guru and a living tradition

- is devoted to the three jewels

- trusts in the laws of karma

- is generous

- brings you to virtuous surroundings

- has tamed the body, speech, and mind

- is gentle and soothing

- has pure perception

- is nonjudgmental

- abides by the Buddha’s rules of Vinaya, Bodhisattvayana, and, of course, Vajrayana

- fears wrongdoing

- is forgiving

- is skillful"

Another book exploring the student-teacher relationship is Alex Berzin’s Wise Teacher, Wise Student: Tibetan Approaches to a Healthy Relationship. The work covers many of the traditional topics but also gives a lot of thought to contemporary issues, cultural differences, and Westerner-specific issues like paranoia and vulnerability. He brings in some models from psychology (transference and regression) to explain many of the dynamics Westerners may present and how students can overcome them.

In general, although it is taught that there are six kinds of masters from whom you receive instruction, the masters who give the pith instructions are your root spiritual masters imbued with threefold kindness. Thus, no discourse or tantra relates a story of the attainment of enlightenment without that individual having relied upon a spiritual master. Each and every one of the highly accomplished masters who appeared in the past relied on material or nonmaterial spiritual masters, and developed all the qualities gained along the paths and stages of awakening; this is a matter of record. Therefore, your lamas have exhausted any flaws and have perfected all qualities: your lamas are the Buddha incarnate. Yet the mind-streams of us ordinary individuals are easily influenced by such things as conditions in our country, our historical period, or our companions. We must thus begin by examining spiritual masters from vantage points both close by and distant, then rely on them having set aside our negative thoughts or attitudes. In the end, having offered service by pleasing the lamas in three ways, and having kept tantric bonds without allowing them to be violated, we train so that our lamas’ wisdom mind and conduct are impressed upon us: our mind and conduct become like a clay image [satsa] emerging from a mold. This is very important.

Dudjom Rinpoche, mentioned above and one of the greatest masters of the 20th century, starts off his magisterial explanation of the foundational practices—A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom: Complete Instructions on the Preliminary Practices, for those embarking on the path of Vajrayana Buddhism—with a long chapter titled “The Qualifications of Masters.”

He concludes it with:

Sublime teachers who are rid of all the faults just described and who possess all the right qualities are, because of the times, very hard to find—like the udumbara, the king of flowers. Even if they should happen to come across such teachers for just a little while, sentient beings with impure perception see faults in them—as has happened many times, starting with Devadatta who saw faults in the Bhagavan. Moreover, most people nowadays have the same store of negative deeds and misfortune, and so they perceive faults as good qualities and good qualities as faults. They see even those who have not a single ability that accords with the Dharma, whether manifest or hidden, as sublime beings, and so on. Those who know how to check are rare indeed. In particular, with regard to giving the profound teachings on the actual condition of things, teachers who have no realization cannot make the ultimate experience and realization develop in their disciples’ mindstreams. We should therefore take this point as a basis and regard a teacher who has most of the right qualities as the equal of the Buddha. The reason for considering even those in whom six of the above sets of qualities are complete and who have most of the right qualities as sublime beings and for following them is described in the Approach to the Absolute Truth:

Because of the age of strife, teachers have a mixture of faults and virtues:

There are none with no negative aspects at all.

Having carefully checked those who have more qualities,

Disciples should put their trust in them.

A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom

$34.95 - Paperback

On Guru Yoga

Whether our teachers present in person are ordinary beings or emanations of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas, if we are able to pray to them considering them as the Buddha, there is absolutely no difference between them and the Buddha or Bodhisattva or yidam deity in person, because the source of blessings is devotion. So whichever profound practice we are undertaking, whether the generation phase or the perfection phase, we should begin by making the teacher’s blessings the path. There is no more to it than that. But as long as we have not received the blessings, we will not be genuinely on the path. It is said that if disciples who keep the commitments give themselves wholeheartedly, with devotion, to an authentic diamond master, they will obtain the supreme and common accomplishments even if they have no other methods. But without devotion to the teacher, even if we complete the approach and accomplishment practices of the yidams of the six tantra sections, we will never obtain the supreme accomplishment. And we will be unlikely to accomplish many of the ordinary accomplishments either, such as those of long life, wealth, or bringing beings under one’s power. Even if we do manage to achieve a little, it will have necessitated a lot of hardship and will have nothing to do with the profound path. When unmistaken devotion takes birth in us, obstacles on the path will be dispelled and we will make progress, obtaining all the supreme and ordinary accomplishments without depending on anything else. This is what we mean by the profound path of Guru Yoga.

A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom

$34.95 - Paperback

“There is one single criterion you should particularly check when examining a teacher: it is whether he has bodhichitta. If he has the bodhichitta, whatever sort of connection one makes with him will be meaningful. A good connection will bring buddhahood in one lifetime, and even a negative connection will eventually bring samsaric existence to an end.”

While one may not be so confident in their bodhicitta detection skills, the point is, after studying and analyzing the teacher, to use your own judgement.

If you wanted more detail, the author presents a more descriptive list of what characteristics to look for.

There are many other traditional overviews that include key instructions for evaluating, committing to, and following a teacher. From the tradition His Holiness the Dalai Lama was first educated in, Tsongkahpa’s The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment covers the subject over several pages. The great 18th-century adept Jigme Lingpa’s Treasury of Precious Qualities beautifully covers this as well.

A Guide to The Words of My Perfect Teacher

$34.95 - Paperback

- How to Seek the Wisdom Teacher

- The Justification for Following the Wisdom Teacher

- Categories and Characteristics of the Master Who Should Be Followed

- The Way in Which One Enters into and Goes Astray—Which Follows from the Characteristics of the Master

- The Characteristics of the Student Who Follows

- How to Follow

- The Necessity of Following the Wisdom Teacher in That Way

- Avoiding Contrary, Harmful Companions

- Creating Faith as a Favorable Condition

- The Way That the Wisdom Teacher Should Explain and the Student Should Listen to the Holy Dharma

Kongtrul relies on sutra and tantra sources to explain each of these. The reader will put it down having a much better appreciation for the scope of the Vajra master and student’s responsibilities, neither of which can be taken lightly.

The Teacher-Student Relationship

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye & Ron Garry & Ven. Gyatrul Rinpoche & Lama Tharchin

Dangerous Friend: The Teacher-Student Relationship in Vajrayana Buddhism by Rig’dzin Dorje focuses exclusively on the Vajrayana aspects of the teacher-student relationship.

Many people are suspicious of Buddhism in general and particularly of the Vajrayana because of the intensity of the guru-disciple relationship. They are made uncomfortable by the level of projections that occur in the interaction of teacher and student. They do not like the lack of explicit restrictions, rules, and limitations on the relationship. They would prefer clear expectations and boundaries, without the uncertainty and intimacy that Vajrayana Buddhism implies.

Without denying the dangers in this as in all other intimate human relationships, and acknowledging that there can be no complete guarantee against mistakes and abuses, still there would appear something shortsighted in this point of view. As long as human beings live in the realm of samsaric duality, there is the inevitability of projection—in this case the positive projections of seeing something ‘‘out there’’ to which we are attracted and that we feel we need. What is sometimes not sufficiently realized is that no human beings are outside of this cycle.

Moreover, projection of this nature is not an inherently bad or undesirable thing. In fact, it is only because we are willing to project, willing to seek our dreams, that we can come up short and begin to integrate the part of ourselves that we had at first seen as outside. People do get ‘‘stuck,’’ but usually not forever. This process always involves vulnerability and suffering, but only in a culture that abhors pain and equates it with evil can one fail to see the transformative element.

The Vajrayana operates by eliciting and provoking the projections of our own deepest nature, then forcing us back on ourselves so that we have to integrate and take possession of those projections. This process is seen no more clearly than in the relation of teacher and student that forms the backbone of the path. Trungpa Rinpoche comments that at the beginning of the path, the teacher is seen virtually as a demigod. In the middle, he is experienced as a friend and companion. And at the end, when we have attained the state of realization that we once saw uniquely in him, he becomes inseparable from the inborn, living wisdom within.

What is sad is not to see this process of projection in Buddhism, where it can lead to something dignified and noble, but to see the way that it operates in the contemporary ‘‘modern’’ world, where it so often leads to an utter dead end. Here, people project their deepest yearnings onto things that have little to do with the human spirit and its maturation—new cars, upscale houses, clothes, vacations, credentials, fame, wealth, and power. It is not surprising, for example, that it is often among those who have succeeded most fully in realizing the materialism of the American Dream that one can find the most emptiness, fear, and unacknowledged despair.

Additional Resources

Another way to approach this is simply to read the stories of great masters and be inspired by their example. Here are a few places to get started:

Khandro Rinpoche

Khandro Rinpoche discusses her teachers in her expansive Refuge chapter in This Precious Life: Tibetan Buddhist Teachings on the Path to Enlightenment

The incomparable lamas of the Longchen Nyintig tradition are presented in Tulku Thondup’s Masters of Meditation and Miracles.

The inspiring stories of Patrul Rinpoche are the subject of Matthieu Ricard’s collection of the oral history of this essential figure, Enlightened Vagabond.

The archetype of students, Milarepa, can be read about in many of the books included in our Reader’s Guide on him.

A subsequent article will address the related topic of Guru Yoga, which lies at the heart of the Vajrayana.

The Importance of the Ornament of Mahayana Sutras

So just what is this text which is quoted everywhere but few have read?

Mipham Rinpoche , paraphrasing Asanga's brother Vasubandu's student Sthiramati, says that this text:

, paraphrasing Asanga's brother Vasubandu's student Sthiramati, says that this text:

. . .explains all the profound and extensive practices of the bodhisattvas, which can be summarized under three headings: what to train in, how to train, and who is training.

The first of these, what one trains in, can be condensed into seven objects in which one trains: one’s own welfare, others’ welfare, thatness, powers, bringing one’s own buddha qualities to maturity, bringing others to maturity, and unsurpassable perfect enlightenment.

How one trains is in six ways: by first developing a great interest in the teachings of the Great Vehicle, investigating the Dharma, teaching the Dharma, practicing the Dharma in accord with the teachings, persevering in the correct instructions and follow-up teachings, and imbuing one’s physical, verbal, and mental activities with skillful means.

Those who train are the bodhisattvas, of whom there are ten categories: those who are of the bodhisattva type, those who have entered the Great Vehicle, those with impure aspirations, those with pure aspirations, those whose aspirations are not matured, those whose aspirations are matured, those with uncertain realization, those with certain realization, those who are delayed by a single birth, and those who are in their last existence.

We have two translations of this text which both include the extensive and illuminating commentary by Mipham Rinpoche who based his long work on Sthiramati's famous commentary.

The first, The Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sutras, was translated by the Dharmachakra Translation Committee includes the annotations by Khenpo Shenga, who derived them often directly from Vasubandu's commentary. You can read our interview with Dharmachakra's Thomas Doctor which includes a short discussion of this text.

Here is the translator from Padmakara, Stephen Gethin, explaining the text.

It is hard to exaggerate the importance of this text in the Tibetan tradition. It was first translated from Sanskrit to Tibetan in the 8th century, at the time of Padmsambhava’s residence, by his disciple Kawa Peltsek. Atisha later taught it when he came to Tibet and refers to it repeatedly throughout his works. Gampopa references it in his Jewel Ornament of Liberation. The great Sakya master Ngorchen Konchog Lhundrub refers to it repeatedly in his Three Visions: Fundamental Teachings of the Sakya Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. Virtually all the great masters of all the Tibetan traditions studied this work and its commentaries in depth.

In short, the Sutralamkara has been central to the training of hundreds of thousands of practitioners and scholars and remains today a core component of all the curriculums in monasteries and shedras.

A Feast of the Nectar of the Supreme Vehicle

$69.95 - Hardcover

By: Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Maitreya & Padmakara Translation Group

Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sutras

$69.95 - Hardcover

By: Dharmachakra Translation Committee & Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Maitreya & Khenpo Shenga

Below are a few more examples showing just how fundamental it is and some ways it is used in later Buddhist literature. And these are a small sampling—this text appears everywhere.

Jamgön Kongtrül brings it forth in his 10 volume Treasury of Knowledge. As an example, in Book Eight he relates how it is a core part of the Kadampa tradition, particularly the training in meditation. He then traces its lineage from Atisha's disciple Drontompa to Potawa to Langri Tampa and onwards to Tsongkhapa and into the present-day Gelug curriculum. He also uses it to prove the validity of the Mahayana.

Tsongkhapa and into the present-day Gelug curriculum. He also uses it to prove the validity of the Mahayana.

The Treasury of Knowledge: Book Eight, Part Four

$59.95 - Hardcover

Longchenpa refers to it throughout his works as pointed out repeatedly in Tulku Thondup's The Practice of Dzogchen. It appears also in the recent translation of Longchenpa's Finding Rest trilogy.

Dudjom Rinpoche brings it into his History of the Nyingma School throughout The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism, in which he calls it the text that teaches “the integration of conduct and view.” He also refers to it repeatedly in A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom when he is explaining the nature of the six perfections.

A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom

$34.95 - Paperback

In Brilliant Moon, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche relates how he and his brother received the instructions on the text. He also brings it up repeatedly in Heart of Compassion, his discussion of the 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva; the power and strength of love; the perfection of wisdom; and the role emotions play to "destroy oneself, destroy others, and destroy discipline." He also mentions it in his biography of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, using phrases describing the nature of bodhisattvas to show how the latter was one.

In his commentary on the 9th chapter of The Way of the Bodhisattva that appears in The Center of the Sunlit Sky, the great Kagyu master Pawo Rinpoche—the student of the 8th Karmapa and teacher to the 9th—devotes thirteen pages to the Sutralamkara explaining how the text proves the validity and authenticity of the Mahayana.

$39.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche & Ani Jinba Palmo & Shechen Rabjam

Tsongkhapa: A Guide to His Life and Works

The Life of Tsongkhapa Lobsang Drakpa (1357-1419)

Tsongkhapa Lobzang Drakpa (1357–1419), was one of the most important figures in Tibet, historically and philosophically. As the founder of the Gelug school he made an enormous contribution to revitalizing Buddhism in Tibet. Regarded as an emanation of Manjushri--the bodhisattva of wisdom and discerning intelligence, Tsongkhapa was of keen intellect as well as experiential understanding of the Buddhist tradition. He undertook many long retreats during which he had profound visions out of which he wrote many of his celebrated treatises including Lam Rim Chenmo or The Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path. A prolific writer, he composed 210 treatises, compiled into 20 volumes wherein he emphasized the combined paths of Sutra and Tanta. In addition, he established the acclaimed Ganden monastery.

For a longer biography of Tsongkhapa read an excerpt from Geshe Sonam Rinchen's commentary on The Three Principal Aspects of the Path.

"Born in 1357 in Amdo, northeastern Tibet, and educated in central Tibet, Tsongkhapa led a life that exemplified the importance of study, critical reflection, and meditative practice. In an autobiographical poem he declared:

"First I sought wide and extensive learning,

Second I perceived all teachings as personal instructions,

Finally, I engaged in meditative practice day and night;

All these I dedicated to the flourishing of the Buddha’s teaching.By the end of his life, 600 years ago, Tsongkhapa was widely revered across Tibet. He had studied and corresponded with the most renowned teachers of his time, from all the major traditions, and had spent years in meditative retreat."

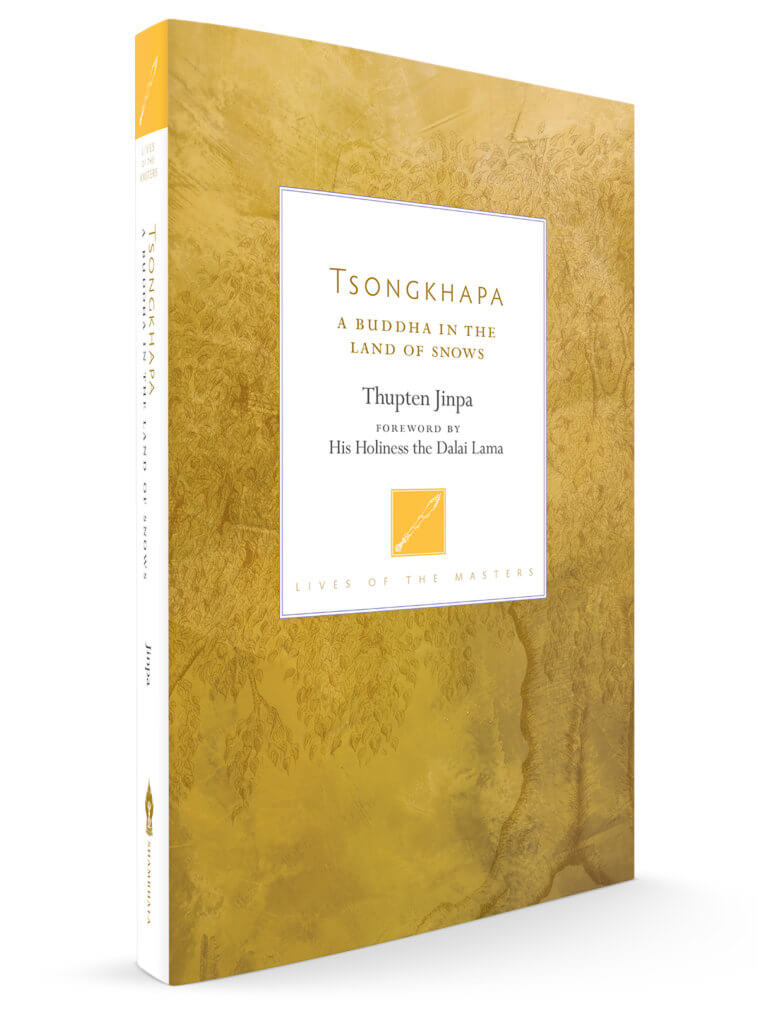

—From the Foreward by H. H. The Dalai Lama, Tsongkhapa: A Buddha in the Land of Snows, by Thupten Jinpa

The Definitive Biography of Tsongkhapa

Paperback | Ebook

$29.95 - Paperback

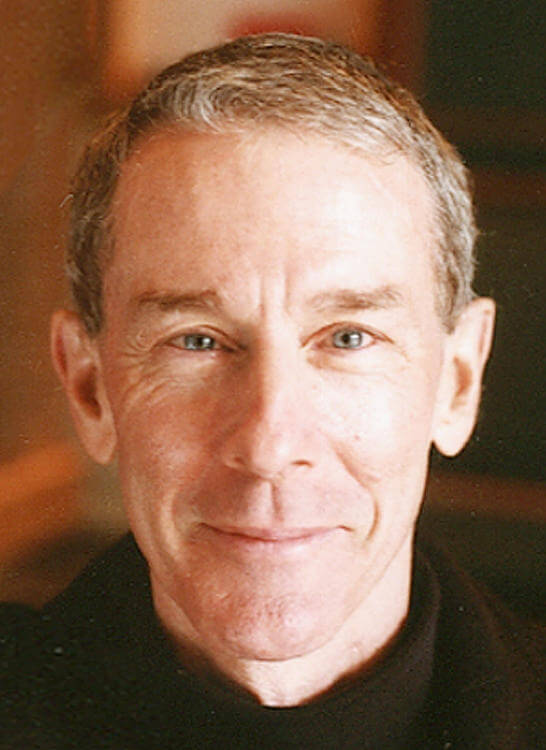

Marking the 600th anniversary of Tsongkhapa, in 2019 we published what is the most comprehensive, definitive biography of this great figure, written by Thupten Jinpa. The author is best known as the main translator for the Dalai Lama, but he is an author and scholar himself, having earned a Geshe degree. In the author’s words,

this new biography of Tsongkhapa…is aimed primarily at the contemporary reader. And it seeks to answer the following key questions for them: ‘Who was or is Tsongkhapa? What is he to Tibetan Buddhism? How did he come to assume the deified status he continues to enjoy for the dominant Geluk School of Tibetan Buddhism? What relevance, if any, do Tsongkhapa’s thought and legacy have for our contemporary thought and culture?

—Thupten Jinpa, from the Introduction to Tsongkhapa: A Buddha in the Land of Snows

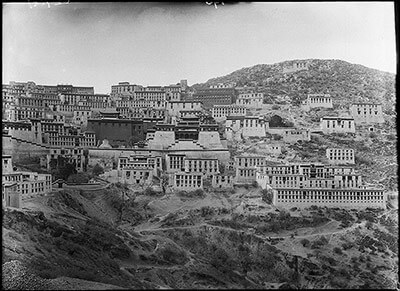

Ganden monastery, founded by Tsongkhapa, photographed in 1921 by Sir Charles Bell

Whoever sees or hears

Or contemplates these prayers,

May they never be discouraged

In seeking the bodhisattva’s amazing aspirations.

By praying with such expansive thought

Created from the power of pure intention,

May I achieve the perfection of prayers

And fulfill the wishes of all sentient beings.

Tsongkhapa's Lam Rim Chenmo, The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment

Tsongkhapa's main contribution to this genre is the famous Lamrim Chenmo or The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. It is also generally considered his most influential work, studied and practiced by tens of thousands today.

The background to this work is on one of Tsongkhapa’s own letters to a lama, included in Art Engle's The Inner Science of Buddhist Practice, where he describes it as building on Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment:

“It is clear that this instruction [introduced] by [Atisha] Dīpaṃkara Śrījnāna on the stages of the path to enlightenment . . . teaches [the meanings contained in] all the canonical scriptures, their commentaries, and related instruction by combining them into a single graded path. One can see that when taught by a capable teacher and put into practice by able listeners it brings order, not just to some minor instruction, but to the entire [body of] canonical scriptures. Therefore, I have not taught a wide variety of [other] instructions.”

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Vol. 1-3)

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Tib. Lam rim chen mo) is one of the brightest jewels in the world’s treasury of sacred literature. The author, Tsong-kha-pa, completed it in 1402, and it soon became one of the most renowned works of spiritual practice and philosophy in the world of Tibetan Buddhism. Because it condenses all the exoteric sūtra scriptures into a meditation manual that is easy to understand, scholars and practitioners rely on its authoritative presentation as a gateway that leads to a full understanding of the Buddha’s teachings.

Tsong-kha-pa took great pains to base his insights on classical Indian Buddhist literature, illustrating his points with classical citations as well as with sayings of the masters of the earlier Kadampa tradition. In this way the text demonstrates clearly how Tibetan Buddhism carefully preserved and developed the Indian Buddhist traditions.

Paperback| Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

(Volume 1)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This first of three volumes covers all the practices that are prerequisite for developing the spirit of enlightenment (bodhicitta).

Paperback| Ebook

$28.95 - Paperback

(Volume 2)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This second of three volumes covers the deeds of the bodhisattvas, as well as how to train in the six perfections.

Paperback| Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

(Volume 3)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This third and final volume contains a presentation of the two most important topics in the work: meditative serenity (śamatha) and supramundane insight into the nature of reality (vipaśyanā).

Commentaries on Tsongkhapa's Great Treatise and other Lam Rim (Stages of the Path) texts

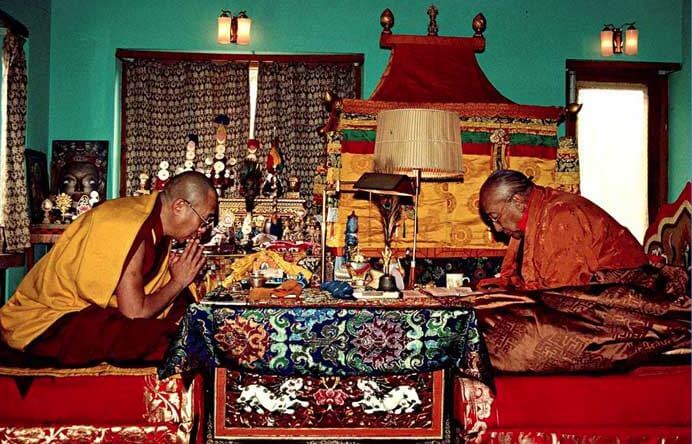

"The Great Treatise was written by Lama Tsong-kha-pa, a great scholar, a real holder of the Nalanda tradition. I think he is one of the very best Tibetan scholars. Although it is now widely available in Tibetan as well as English, you see that I brought with me today my own personal copy of this text. On March 17th, 1959, when I left Norbulingka that night, I brought this book with me. Since then I have used it ten or fifteen times to give teachings, all from this copy. So this is something very dear to me."

-H.H The Dalai Lama discussing his copy of the Great Treatise in From Here to Enlightenment

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

From Here to Enlightenment

An Introduction to Tsong-kha-pa's Classic Text The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment

By H.H. The Dalai Lama and translated by Guy Newland

When the Dalai Lama was forced into exile in 1959, he could take only a few items with him. Among these cherished belongings was his copy of Tsong-kha-pa’s classic text The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. This text distills all the essential points of Tibetan Buddhism, clearly unfolding the entire Buddhist path.

In 2008, celebrating the long-awaited completion of the English translation of the Great Treatise, the Dalai Lama gave a historic six-day teaching at Lehigh University to explain the meaning of the text and underscore its importance. It is the longest teaching he has ever given to Westerners on just one text—and the most comprehensive. From Here to Enlightenment makes the teachings from this momentous event available for a wider audience.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

Introduction to Emptiness

As Taught in Tsong-kha-pa's Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path

By Guy Newland

Readers are hard-pressed to find books that can help them understand the central concept in Mahayana Buddhism—the idea that ultimate reality is emptiness. In clear language, Introduction to Emptiness explains that emptiness is not a mystical sort of nothingness, but a specific truth that can and must be understood through calm and careful reflection. Newland's contemporary examples and vivid anecdotes will help readers understand this core concept as presented in one of the great classic texts of the Tibetan tradition, Tsong-kha-pa's Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. This new edition includes quintessential points for each chapter.

Paperback | Ebook

$17.95 - Paperback

Refining Gold

Stages in Buddhist Contemplative Practice

By H.H. The Dalai Lama

In this extensive teaching, the Dalai Lama beautifully elucidates the meaning of the path to enlightenment through his own direct spiritual advice and personal reflections. Based on two very famous Tibetan text—Tsongkhapa's Song of the Stages on the Spiritual Path and the Third Dalai Lama's Essence of Refined Gold—this teaching presents in practical terms the essential instructions for the attainment of enlightenment. Its direct approach and lucid style make Refining Gold one of the most accessible introductions to Tibetan Buddhism ever published. His discourse draws out the meaning of the Third Dalai Lama’s famous Essence of Refined Gold as he speaks directly to the reader, offering advice, personal reflections, and scriptural commentary. He says in practical terms what the student must do to attain enlightenment.

Tsongkhapa's Three Principle Aspects of the Path

This is the shortest Lamrim text Tsongkhapa composed. Tsongkhapa wrote the fourteen stanzas of this classic distillation of all the paths of practice that lead to enlightenment. The three principal elements of the path referred to are: (1) renunciation, tied to the wish for freedom from cyclic existence; (2) the motivation to attain enlightenment for the benefit of others; (3) cultivating the correct view that realizes emptiness.

Paperback | eBook

$21.95 - Paperback

Three Principal Aspects of the Path

By Geshe Sonam Rinchen, edited and translated by Ruth Sonam

The wish for freedom, the altruistic intention, and the wisdom realizing emptiness constitute the essence of the Buddhist path. In this teaching, Geshe Sonam Rinchen explains, in clear and readily accessible terms, Je Tsongkhapa’s (1357–1419) famed presentation of these three essential topics.

The Three Principal Aspects is also included in Cutting Through Appearances: Practice and Theory of Tibetan Buddhism in which Geshe Sopa annotates the Fourth Panchen Lama’s instructions on how to practice this text in a meditation session.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama teaches on this text, and this is included as the chapter “The Path to Enlightenment” in Kindness, Clarity, and Insight.

Paperback | Ebook

$39.95 - Paperback

Paperback | Ebook

$16.95 - Paperback

Paperback | eBook

$29.95 - Paperback

Another work where Tsongkhapa’s Lamrim is featured is in Changing Minds: Contributions to the Study of Buddhism and Tibet in Honor of Jeffrey Hopkins. There are three chapters devoted to Tsongkhapa:

- Guy Newland’s Ask a Farmer: Ultimate Analysis and Conventional Existence in Tsongkhapa’s Lam Rim Chen Mo

- Daniel Cozort’s Cutting the Roots of Virtue: Tsongkhapa on the Results of Anger

- Elizabeth Napper’s Ethics as the Basis of a Tantric Tradition: Tsongkhapa and the Founding of the Gelugpa Order

Lotsawa House also includes a translation of these fourteen stanzas.

Tsongkhapa on Madhyamaka, The Middle Way School

Tsongkhapa is known for his distinct approach to the middle way philosophical system (madhyamaka) propounded by Indian masters Nāgārjuna (circa 200 CE) and Candrakīrti (circa 600 CE).

"I first went to India in 1972 on a dissertation research Fulbright fellow-ship, where although advised by the Fulbright Commission in New Delhi not to go to Dharmsala because of possible political complications, I went after a brief trip to Banaras. There I found that the Dalai Lama was about to begin a sixteen-day series of four- to six-hour lectures on Tsong-kha-pa Lo-sang-drak-pa’s Medium-Length Exposition of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment Practiced by Persons of Three Capacities. Despite my cynicism that a governmentally appointed reincarnation could possibly have much to offer, I slowly became fascinated first with the strength and speed of his articulation and then, much more so, with the touching meanings that were conveyed."

-Jeffrey Hopkins, from the Preface to Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom

Paperback | eBook

$44.95 - Paperback

Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom

By Jeffrey Hopkins

In fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Tibet there was great ferment about what makes enlightenment possible, since systems of self-liberation must show what factors pre-exist in the mind that allow for transformation into a state of freedom from suffering. This controversy about the nature of mind, which persists to the present day, raises many questions. This book first presents the final exposition of special insight by Tsong-kha-pa, the founder of the Ge-luk-pa order of Tibetan Buddhism, in his medium-length Exposition of the Stages of the Path as well as the sections on the object of negation and on the two truths in his Illumination of the Thought: Extensive Explanation of Chandrakirti's Supplement to Nagarjuna's "Treatise on the Middle." It then details the views of his predecessor Dol-po-pa Shay-rap Gyel-tsen, the seminal author of philosophical treatises of the Jo-nang-pa order, as found in his Mountain Doctrine, followed by an analysis of Tsong-kha-pa's reactions. By contrasting the two systems—Dol-po-pa's doctrine of other-emptiness and Tsong-kha-pa's doctrine of self-emptiness—both views emerge more clearly, contributing to a fuller picture of reality as viewed in Tibetan Buddhism. Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom brilliantly explicates ignorance and wisdom, explains the relationship between dependent-arising and emptiness, shows how to meditate on emptiness, and explains what it means to view phenomena as like illusions.

Paperback

$34.95 - Paperback

The Ornament of the Middle Way

A Study of the Madhyamaka Thought of Santaraksita

By James Blumenthal

The late James Blumenthal explores this important text by Shantarakshita and brings in Tsongkhapa’s text on this subject.

Shantarakshita's The Ornament of the Middle Way is among the most important Mahayana Buddhist philosophical treatises to emerge on the Indian subcontinent. In many respects, it represents the culmination of more than 1300 years of philosophical dialogue and inquiry since the time of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. Shantarakshita set forth the foundation of a syncretic approach to contemporary ideas by synthesizing the three major trends in Indian Buddhist thought at the time (the Madhyamaka thought of Nagarjuna, the Yogachara thought of Asanga, and the logical and epistemological thought of Dharmakirti) into one consistent and coherent system. Shantarakshitas's text is considered to be the quintessential exposition or root text of the school of Buddhist philosophical thought known in Tibet as Yogachara-Svatantrika-Madhyamaka. In addition to examining his ideas in their Indian context, this study examines the way Shantarakshita's ideas have been understood by and have been an influence on Tibetan Buddhist traditions. Specifically, Blumenthal examines the way scholars from the Geluk School of Tibetan Buddhism have interpreted, represented, and incorporated Santaraksita's ideas into their own philosophical project. This is the first book-length study of the Madyamaka thought of Shantarakshita in any Western language. It includes a new translation of Shantarakshita's treatise, extensive extracts from his autocommentary, and the first complete translation of the primary Geluk commentary on Shantarakshita's treatise.

"As a religious reformer, he has been likened to Luther by Western Buddhologists; but as a religious scholar he is regarded in his own culture as a genius whose statue more closely parallels that of Aquinas in Western Christianity. For Tsongkhapa created his own unique interpretation of Buddhist systematics and hermeneutics, in which he synthesized themes from all the Tibetan Buddhist traditions of his era. For these reasons he was praised by the Eight Karmapa as Tibet's chief exponent of ultimate truth, who revived the Buddha's doctrine at a time when the teachings of all four major Tibetan Buddhist lineages were in decline."

-B. Alan Wallace, from the Preface to Balancing the Mind

Paperback | eBook

$24.95 - Paperback

Balancing the Mind

A Tibetan Buddhist Approach to Refining Attention

By B. Alan Wallace

For centuries, Tibetan Buddhist contemplatives have directly explored consciousness through carefully honed and rigorous techniques of meditation. B. Alan Wallace explains the methods and experiences of Tibetan practitioners and compares these with investigations of consciousness by Western scientists and philosophers. Balancing the Mind includes a translation of the classic discussion of methods for developing exceptionally high degrees of attentional stability and clarity by fifteenth-century Tibetan contemplative Tsongkhapa.

Tsongkhapa and the Debate over the Two Truths

Tsongkhapa is famous—and in some circles controversial—for his presentation and positioning of the Prasangika view of Madhyamaka. Any discussion or debate of this subject invariably references Tsongkhapa.

Hardcover | eBook

$78.00 - Hardcover

The Center of a Sunlight Sky

Madhyamaka in the Kagyu Tradition

By Karl Brunnhölzl

This comprehensive work by Karl Brunnholzl explores all facets of Madhyamaka in the Kagyu tradition, but no analysis of Madhyamaka can leave out Tsongkhapa who appears throughout this work. There is a sixty-page section comparing the views of Tsongkhapa to those of Mikyo Dorje’s “whose writing, not only is a reaction to the position of Tsongkhapa and his followers but addresses most of the views on Madhyamaka that were current in Tibet at the time, including the controversial issue of ‘Shentong-Madhyamaka.’”

Paperback| eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Adornment of the Middle Way

Shantarakshita's Madhyamakalankara with Commentary by Jamgon Mipham

By Jamgon Mipham, translated by Padmakara Translation Group

For a different take on Shantarakshita's The Ornament of the Middle Way (same text, differently translated title) The Adornment of the Middle Way translated by the Padmakara Translation Group, gives a helpful introduction on the various interpretations. This longer passage offers a glimpse into some of the fault lines in the debate:

"The brilliance of Tsongkhapa’s teaching, his qualities as a leader, his emphasis on monastic discipline, and the purity of his example attracted an immense following. Admiration, however, was not unanimous, and his presentation of Madhyamaka in particular provoked a fierce backlash, mainly from the Sakya school, to which Tsongkhapa and his early disciples originally belonged. These critics included Tsongkhapa’s contemporaries Rongtön Shakya Gyaltsen (1367–1449) and Taktsang Lotsawa (1405–?), followed in the next two generations by Gorampa Sonam Senge (1429–1487), Serdog Panchen Shakya Chokden (1428–1509), and the eighth Karmapa, Mikyö Dorje (1505–1557). All of them rejected Tsongkhapa’s interpretation as inadequate, newfangled, and unsupported by tradition. Although they recognized certain differences between the Prasangika and Svatantrika approaches, they considered that Tsongkhapa had greatly exaggerated the divergence of view. They believed that the difference between the two subschools was largely a question of methodology and did not amount to a disagreement on ontological matters.

Not surprisingly, these objections provoked a counterattack, and they were vigorously refuted by Tsongkhapa’s disciples. In due course, however, the most effective means of silencing such criticisms came with the ideological proscriptions imposed at the beginning of the seventeenth century. These followed the military intervention of Gusri Khan, who put an end to the civil war in central Tibet, placed temporal authority in the hands of the Fifth Dalai Lama, and ensured the rise to political power of the Gelugpa school. Subsequently, the writings of all the most strident of Tsongkhapa’s critics ceased to be available and were almost lost. It was, for example, only at the beginning of the twentieth century that Gorampa’s works could be fully reassembled, whereas Shakya Chokden’s works, long thought to be irretrievably lost, were discovered only recently in Bhutan and published as late as 1975."

-from the Introduction to The Adornment of the Middle Way

The Wisdom Chapter

Jamgön Mipham's Commentary on the Ninth Chapter of The Way of the Bodhisattva

By Jamgon Mipham, translated by Padmakara Translation Group

This work on the Wisdom Chapter of Shantideva’s classic, written more than four centuries after Tsongkhapa, is a presentation of a different view than that expounded by Tsongkhapa. It is, in fact, a superb source for understanding the impact of his Madhyamaka presentation in a wider context, historically and philosophically. The extensive introduction gives a very complete and comprehensive account. In sum:

"In his treatment of the Gelugpa account, Mipham concurs in all important respects with Gorampa and the rest of Tsongkhapa’s earlier critics. Indeed, his critique is possibly even more effective in being expressed moderately and without vituperation. Nevertheless, he is careful never to attack Tsongkhapa personally. Given the fact that Mipham was a convinced upholder of the nonsectarian movement, there is no reason to doubt the sincerity of the humble and respectful manner with which he invariably refers to Tsongkhapa. No sarcasm is detectable in his words:

In the snowy land of Tibet, the great and venerable lord Tsongkhapa was unrivaled in his activities for the sake of the Buddha’s teaching. And with regard to his writings, which are clear and excellently composed, I do indeed feel the greatest respect and gratitude.

There is, however, a striking contrast between Mipham’s veneration of Tsongkhapa, on the one hand, and his penetrating critique of his view, on the other. Mipham’s assessment seems to oscillate between an approbation of some of Tsongkhapa’s positions, regarded as unproblematic expressions of a Svātantrika approach that Mipham valued, and a determination to demolish Tsongkhapa’s philosophical innovations and their pretended Prāsaṅgika affiliations. This discrepancy has led some scholars to accuse Mipham of inconsistency. Closer scrutiny suggests, however, that Mipham’s admittedly complex attitude to Tsongkhapa was in point of fact quite coherent."

-from the Introduction to The Wisdom Chapter

Tsongkhapa's Poetry and Songs of Realization

Paperback

$22.95 - Paperback

Thupten Jinpa’s collection of Tibetan poetry includes two poems by Tsongkhapa including Reflections on Emptiness, which is extracted from a larger work, the rTag tu ngu’i rtogs brjod—a poetic retelling of the story of the bodhisattva Sadāprarudita, who is associated with the 8,000 Verse Prajnamaramita Sutra and A Prayer for the Flourishing of Virtues.

Jinpa presents Tsongkhapa’s poetry first in terms of his mastery of composition and second, in terms of his mastery of the Buddhist path.

First, describing his master of composition, Jinpa writes:

Tsongkhapa’s famous long poem entitled ‘‘A Literary Gem of Poetry’’ uses a single vowel in every stanza throughout the entire length. This is the poem from which come the famous lines:

Good and evil are but states of the heart:

When the heart is pure, all things are pure;

When the heart is tainted, all things are tainted.

So all things depend on your heart.In the original Tibetan, this stanza uses only the vowel a. Of course, this kind of literary device can never be reproduced in a translation, whatever the virtuosity and command of the translator.

Second, describing his mastery of the Buddhist path Jinpa states:

To a contemporary reader, Tsongkhapa’s famous ‘‘Prayer for the Flourishing of Virtues’’ gives an insight into the deepest ideals of a dedicated Tibetan Buddhist practitioner; it presents a map of progressive development on the path. Beyond this, the mystic must utterly transform the very root of his identity and the perceptions that arise from it. From the ordinary patterns of action and reaction that make up our psyche and emotional life, the meditator must move toward a divine state of altered consciousness where all realities, including one’s own self, are manifested in their enlightened forms. In other words, the meditator must perfect all dimensions of his or her identity and experience, including rationality, emotion, intuition, and even sexuality. This, in Tibetan Buddhism, is the mystical realm of tantra.

Tsongkhapa and Tantra

A brief note. For those unfamiliar or only exposed through books, we strongly encourage readers to study tantra under the guidance of a qualified teacher. Book reading can only take you so far as the transmission of tantric teaching is about more than what can be put on paper.

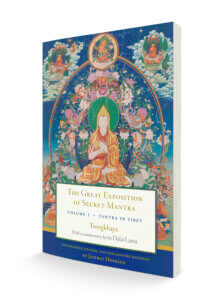

This work is analogous to the tantra version of the Lamrim Chenmo, presenting tantra from the position of the sarma, ie., the 'new school,' or later transmission from India.

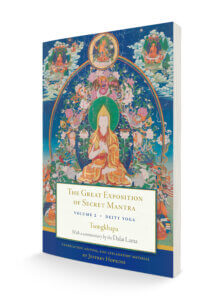

There are three books by Tsongkhapa and His Holiness the Dalai Lama that form a series focused on Tsongkhapa's Great Exposition of Secret Mantra. In this text, Tsongkhapa presents the differences between sutra and tantra and the main features of various systems of tantra. Each of the three books below begins with the Dalai Lama contextualizing and commenting on the points presented in Tsongkhapa's text, followed by a translation of the corresponding part of the text itself.

Paperback

$29.95 - Paperback

In Volume 1: Tantra in Tibet, the foundations of motivation, refuge, and the Hinayana and Mahayana paths are presented. He then gives an overview of tantra, the notion of Clear Light, the greatness of mantra, and initiation or empowerment.

This revised work describes the differences between the Great Vehicle and Lesser Vehicle streams in the sutra tradition, and between the sutra tradition and that of tantra generally. It includes highly practical and compassionate explanations from H.H. the Dalai Lama on tantra for spiritual development; the first part of the classic Great Exposition of Secret Mantra text; and a supplement by Jeffrey Hopkins on the difference between the Vehicles, emptiness, psychological transformation, and the purpose of the four tantras.

Paperback

$29.95 - Paperback

In Volume II: Deity Yoga, His Holiness discusses deity yoga at length with a particular focus on action and performance tantras (the first two categories of tantra as described in the sarma, or “new translation” schools).

This revised work describes the profound process of meditation in Action (kriya) and Performance (carya) Tantras. Invaluable for anyone who is practicing or is interested in Buddhist tantra, this volume includes a lucid exposition of the meditative techniques of deity yoga from H.H. the Dalai Lama; the second and third chapters of the classic Great Exposition of Secret Mantra text; and a supplement by Jeffrey Hopkins outlining the structure of Action Tantra practices as well as the need for the development of special yogic powers.

Paperback

$27.95 - Paperback

in Volume III: Yoga Tantra the Dalai Lama details the practice of the next level of tantra, yoga tantra. With a preliminary overview of the motivation, His Holiness explains this level, which focuses on internal yoga, which here means the union of deity yoga with the wisdom of realizing emptiness. He details the yoga, both that with and that without signs, and then briefly explains how gaining stability in these practices is the foundation for some other practices that lead to mundane and extraordinary “feats.”

This work opens with the Dalai Lama presenting the key features of Yoga Tantra then continues with the root text by Tsongkhapa. This is followed by an overview of the central practices by Khaydrub Je. Jeffrey Hopkins concludes the volume with an outline of the steps of Yoga Tantra practice, which is drawn from the Dalai Lama’s, Tsongkhapa’s, and Khaydrub Je’s explanations.

An explanation of the highest yoga tantra is not included in these works, but an excellent resource is Daniel Cozort's Highest Yoga Tantra.

Paperback

$39.95 - Paperback

The Six Yogas of Naropa

Tsongkhapa's Commentary

By Glenn H. Mullin

Tsongkhapa's commentary entitled A Book of Three Inspirations: A Treatise on the Stages of Training in the Profound Path of Naro's Six Dharmas is commonly referred to as The Three Inspirations. Anyone who has read more than a few books on Tibetan Buddhism will have encountered references to the Six Yogas of Naropa, a preeminent yogic technology system. The six practices—inner heat, illusory body, clear light, consciousness transference, forceful projection, and bardo yoga—gradually came to pervade thousands of monasteries, nunneries, and hermitages throughout Central Asia over the past five and a half centuries.

Paperback

$27.95 - Paperback

The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa

By Glenn H. Mullin

Another text that is included in Tsongkhapa’s collected works is the short Practice Manual on the Six Yogas. This is included in the wider collection of texts on this practice titled The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa. Also included in this book are works by Tilopa, Naropa, Je Sherab Gyatso, and the First Panchen Lama.

From the Six Yogas of Naropa:

"Tsongkhapa's treatise on this system of tantric practice ... became the standard guide to the Naropa tradition at Ganden Monastery, the seat he founded near Lhasa in 1409. Ganden was to become the motherhouse of the Gelukpa school, and thus the symbolic head of the network of thousands of Gelukpa monasteries that sprang up over the succeeding centuries across Central Asia, from Siberia to northern India. A Book of Three Inspirations has served as the fundamental guide to Naropa's Six Yogas for the tens of thousands of Gelukpa monks, nuns, and lay practitioners throughout that vast area who were interested in pursuing the Naropa tradition as a personal tantric study. It has performed that function for almost six centuries now.

Tsongkhapa the Great's A Book of Three Inspirations has for centuries been regarded as special among the many. The text occupies a unique place in Tibetan tantric literature, for it in turn came to serve as the basis of hundreds of later treatments. His observations on various dimensions and implications of the Six Yogas became a launching pad for hundreds of later yogic writers, opening up new horizons on the practice and philosophy of the system. In particular, his work is treasured for its panoramic view of the Six Yogas, discussing each of the topics in relation to the bigger picture of tantric Buddhism, tracing each of the yogic practices to its source in an original tantra spoken by the Buddha, and presenting each within the context of the whole. His treatise is especially revered for the manner in which it discusses the first of the Six Yogas, that of the 'inner heat.' As His Holiness the present Dalai Lama put it at a public reading of and discourse upon the text in Dharamsala, India, in 1991, 'the work is regarded by Tibetans as tummo gyi gyalpo, the king of treatments on the inner heat yoga.' Few other Tibetan treatises match it in this respect."

Paperback | eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

This work has three main sections: an overview of Mahamudra, the First Panchen’s text The Main Road of the Triumphant Ones, and a commentary by the Dalai Lama. The author contextualizes the selection saying that the tradition of Mahamudra in the Gelug tradition comes through Tsongkhapa.

Other Notable Works Related to Tsongkhapa

Paperback | eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

Tibetan Literature

Studies in Genre

Edited by Jose Cabezon and Roger R. Jackson

Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre is a collection by leading Tibetologists. The immensity of Tibet's literary heritage, unsurprisingly, is filled with references to Tsongkhapa across a wide range of subjects. Just a sampling of them include: the establishment of the Gelug order; the monastic curriculum; debate manuals; establishment of Ganden; a comparison with Milarepa; the controversies about his views; a classification of his texts; and a lot more.

Paperback | eBook

$29.95 - Paperback

Mind in Tibetan Buddhism

By Lati Rinpoche, Edited and translated by Elizabeth Napper

Mind in Tibetan Buddhism is an oral commentary on Geshe Jampel Sampel's Presentation of Awareness and Knowledge Composite of All the Important Points, Opener of the Eye of New Intelligence. This topic, lorig in Tibetan, was not one on which Tsongkhapa wrote a dedicated text, but he does include it in an introduction to Dharmakirti’s Seven Treatises and one of his sections includes a brief presentation on lorig. Tsongkhapa is brought up throughout this book.

Tsongkhapa is also referenced in about 60 articles on shambhala.com, mostly from the Snow Lion newsletter archive.

Additional Resources

More can be found on Atisha's life on Treasury of Lives

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

The Dalai Lama: Reliance on a Teacher

This article on reliance on a teacher originally appeared in the Snow Lion newsletter, Vol 12 #4, Fall 1997

Answers to Questions at the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center, Washington, New Jersey, September 1990

Joshua Cutler: Americans in general are very wary of relying on one person and giving that person a lot of power and control. This is difficult for American people. But on the other hand, I know that, when the teaching was coming from India to Tibet, Atisha was asked by Dromtonpa, "How is it that we Tibetans have such a good knowledge of the teachings yet no one has produced any of the realizations of the grounds and the paths?" Atisha replied that it was because Tibetans were still viewing the teacher as an ordinary person. It’s very clear to me that this teaching of faith in the spiritual teacher is the very foundation of the teaching being able to grow in this country, but there is a problem because many spiritual teachers have abused their students and so people are very suspicious of teachers. Could Your Holiness please give us guidance on this practice of relying upon the spiritual teacher?

Related Books

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

$19.95 - Paperback

By: Atisha & Geshe Sonam Rinchen & Ruth Sonam