To truly understand Tibetan Buddhism, one must come to grips with the unique role of the teacher, the dynamics of the teacher-student relationship, and the possibilities that having a teacher can open up.

Tibetan Buddhism is composed of the Vajrayana or Tantric teachings on top of a foundation of the Sutrayana (vehicle of the Sutras), the core teachings of what are sometimes called the Sravakayana and the Mahayana. In the context of the Sutrayana, a relationship with a teacher roughly maps to the categories of a pratimoksha master and a master of the bodhisattva vows, but there is a wide scope of possibilities and overlap within these roles. The teacher imparts, for example, important points on shamatha or vipashyana meditation, philosophy, or techniques like mind training (lojong), and these are akin to the role of teachers in other Buddhist traditions.

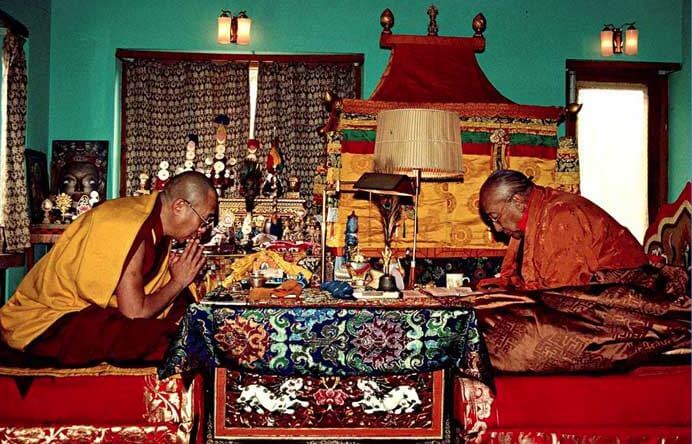

But in the relationship with a male or female vajra master in the context of tantric teachings, including Mahamudra and Dzogchen, the teacher and student have very specific commitments to each other, which is a very different situation. While this relationship may very well incorporate the elements of the relationship with a Sutrayana teacher, it is important for people to understand that a Vajrayana teacher is not really akin to the role of the Zen priest or the spiritual friend (kalyāṇamitta) of the Pali tradition of Buddhism, let alone the Hindu Guru, therapist, or a modern-day life coach. The practice of Guru Yoga (see sidebar below), whereby the student visualizes their teacher in the form of an enlightened being is one example of how different things are in this context. The relationship is much more central and is an essential mechanism for making great strides on the path.

That is why traditional texts encourage people to spend up to 12 years carefully considering whether a teacher of Vajrayana is suitable for them. They are not encouraging people to be wishy-washy and put off making a commitment; rather, this number underlines the importance of choosing a teacher very carefully.

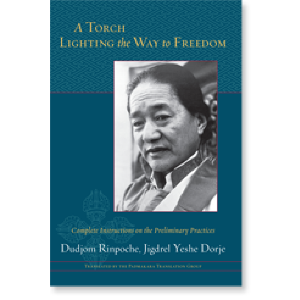

The benefits are immeasurable and are not accessible without a teacher. The great 20th-century master Dudjom Rinpoche gives some traditional examples to demonstrate the importance:

Ordinary, childlike beings are incapable of proceeding even vaguely in the same direction as the perfect path by the strength of their own minds, so they need first to examine and then to follow a qualified diamond master. Diamond masters are the root that causes us to correctly engage in the whole Buddhadharma in general and especially to follow the path properly. They are knowledgeable and experienced guides for inexperienced travellers setting out on a journey, powerful escorts for those who are travelling to dangerous places, ferrymen steering the boat for people crossing a river. Without them, nothing is possible. This is reiterated in countless scriptures.

Recently, there has been a lot of news and discussion in the media, Buddhist and otherwise, around the role of the teacher in Buddhism—in particular, Tibetan Buddhism. This mostly relates to a small handful of teachers (including the leader of Shambhala International, an organization totally unaffiliated with Shambhala Publications) against whom there have been serious allegations of abuse of power, some of it sexual. Many of these articles have been read by a younger generation of Westerners curious about Buddhism and other spiritual traditions but suspicious of hierarchy, organized religion, and spiritual leaders with perceived authority. This media attention seems to validate their suspicions.

But however bad some of these cases are—and it should go without saying that someone who is causing harm is acting in complete opposition to the Buddhadharma—a teacher harming or taking advantage of a student is an unacceptable exception to the norm; it is a rare aberration in an incredible system that has benefited millions of people East and West in the most profound and transformative ways.

These aberrations are not new. People are human, and throughout Buddhist history (or any tradition) there has been the occasional charlatan or flawed leader—as the discussion of how to avoid a bad teacher in many of the texts below make plain. But the fact is that there are so many highly educated, spiritually accomplished (typically following many years in retreat), caring, selfless teachers in this tradition, and it is a shame that people who do not know better are being exposed, online and in print, only to the exceptions rather than the norm and the potential.

Specifically, much of the recent coverage and discussion online and in print around the role of the guru or lama has reflected a deep misunderstandings of the role of the teacher in Tibetan Buddhism and has therefore created a lot of confusion. The best way for a student to find the right teacher who can lead them far along the path to enlightenment is to have a solid ground in understanding what the roles are, to be aware of the cultural dynamics at play, and to know which qualities to seek and which to avoid.

So, we are pleased to share this Reader’s Guide to help those interested in understanding the role, importance, and centrality of the guru or lama and the transformative power of the student-teacher relationship. We hope this will better prepare those pursuing this path to understand the choices they are making and set them up for spiritual success and accomplishment.