What follows is a guide to some of our books and other resources available on Shambhala.com that relate to the Drikung Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The Drikung lineage comes from Marpa, Milarepa, and Gampopa through Phagmo Drupa and Jigten Sumgön, who is considered the root of the tradition. His most famous work, the Gongchik, or “Single Intention,” is a collection of profound statements summarizing the entirety of the Buddhist path for which several famous commentaries have been written. Jigten Sumgön (1143–1217) is also known for his special teachings on Mahayana, Mahamudra, and the Six Yogas of Naropa. After Jigten Sumgön established a monastery and retreat center at Drikung Thil in central Tibet, the lineage flourished, becoming one of the most influential Tibetan Buddhist traditions. Over the centuries the Drikung Kagyu have established monasteries throughout Tibet and the greater Himalayan region, and have recently established meditation centers internationally, including in the United States, Germany, and Vietnam.

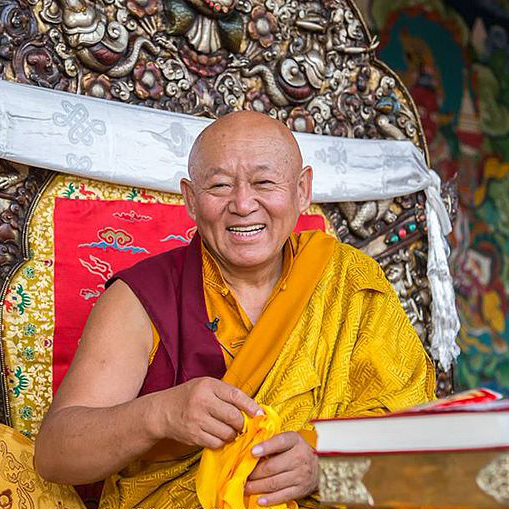

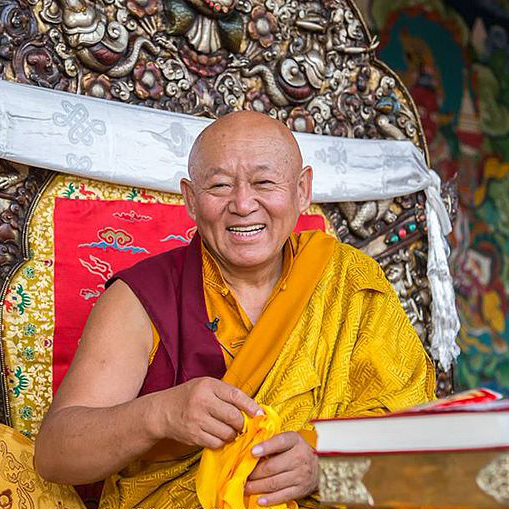

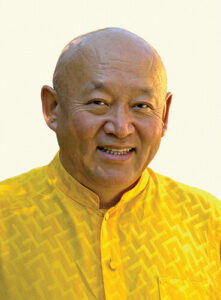

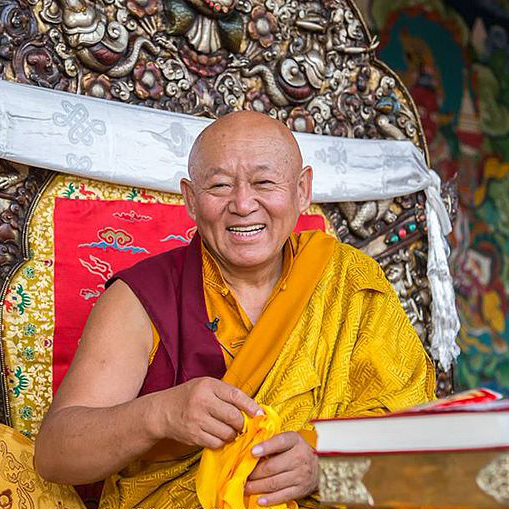

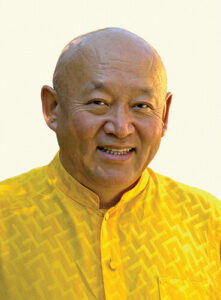

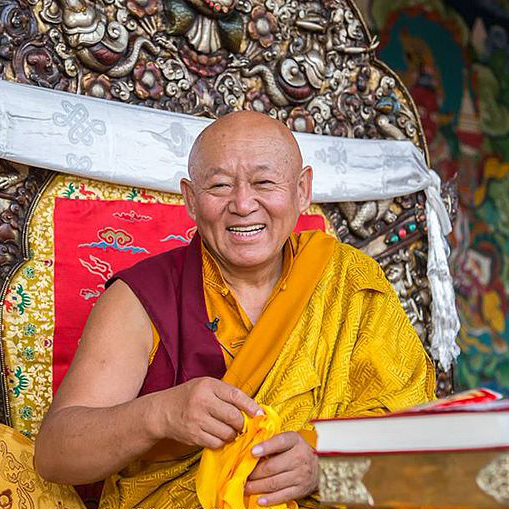

Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche

His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche is the thirty-seventh Drikung Kyabgon head of the Drikung Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism. He has worked tirelessly to renew and spread its scholarly and meditative traditions in many countries, including the United States. He lives at the seat of the Drikung Kagyu order in Dehra Dun, India.

Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche

-

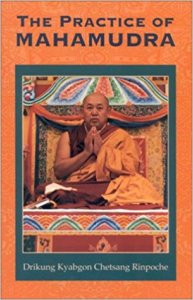

The Practice of Mahamudra$27.95- Paperback

The Practice of Mahamudra$27.95- PaperbackBy Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche

Edited by Ani K. Trinlay Chodron

Translated by Robert Clark

GUIDES

The Drikung Kagyu: A Reader's Guide

The Head of the Drikung Kagyu

The current heads of the lineage are His Holiness Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche and His Holiness Drikung Kyabgon Chungtsang Rinpoche. His Holiness Chungtsang Rinpoche still resides and teaches in Tibet in Lhasa, while His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche lives in India and regularly travels throughout the world to impart Buddhist teachings.

The story of His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche is at once amazing, heartbreaking, and inspiring. It is told in From the Heart of Tibet: The Biography of Drikung Chetsang Rinpoche, the Holder of the Drikung Kagyu Lineage. This biography traces His Holiness's journey from his recognition as a tulku and early training to an oppressed life under the Chinese to his escape to India and then to the United States and eventually back to India, where he founded the Drikung Kagyu Institute, the Songtsen Library, and Samtenling Nunnery. His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche has also established retreat centers both in India and abroad. His Holiness is an avid historian, environmentalist, and a passionate advocate for world peace.

The Drikung Kagyu are well known for their unique presentation of the Five Paths of Mahamudra, a program that includes: arousing bodhichitta, deity visualization, guru yoga, Mahamudra meditation, and finally, dedication of merit. In The Practice of Mahamudra, His Holiness presents this fivefold teaching, which includes advice from Tilopa and Gampopa.

$27.95 - Paperback

By: Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche & Khenmo Trinlay Chodron & Robert Clark

New Releases

Kyabje Garchen Rinpoche is a Buddhist teacher of the Drikung Kagyu tradition. In Vajrakilaya he offers a complete manual for the visualization and supplication of the deity Vajrakīlaya. This ancient tantric practice centers on familiarizing oneself with the wrathful deity as a method for traversing the path to enlightenment. With clear instructions and insightful commentary, Garchen Rinpoche highlights the cultivation of bodhicitta at every stage of the path. This comprehensive guide to deity practice by one of the greatest living Tibetan meditation masters will support practitioners of all experiential levels in reuniting with their own awakened nature.

Works from Khenchen Konchog Gyaltsen

Khenchen Konchog Gyaltsen is another great contemporary scholar of the Drikung and has published multiple works with an emphasis on the Drikung Kagyu teachings.

Opening the Treasure of the Profound: Teachings on the Songs of Jigten Sumgön and Milarepa is a wonderful collection of vajra songs. It also includes over sixty pages on Jigten Sumgön by His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche, Ngorje Repa (a student of Sakya Sribhadra and Jigten Sumgön) and Drikung Kyabgon Padmai Gyaltsen.

A Complete Guide to the Buddhist Path is Khenchen's presentation of The Jewel Treasury of Advice, a text composed by Drikung Bhande Dharmaradza (1704–1754), the reincarnation of Drikung Dharmakirti, Rigdzin Chokyi Drakpa (1595–1659). This work includes advice for meditators, Mahayana practitioners, and Vajrayana practitioners. The teachings include Mahamudra preparation and practice, dispelling obstacles, the Six Yogas of Naropa, and the final result of practice.

The Great Kagyu Masters: The Golden Lineage Treasury brings the lives and teachings of many of the great Kagyupas to light. From Vajradhara to Jigten Sumgön, this collection also includes Shakyamuni Buddha himself, Tilopa, Naropa, the Four Great Dharma Kings, Marpa, Milarepa, Atisha, Gampopa, Phagmo Drupa, and more.

The Garland of Mahamudra Practices is a translation of Clarifying the Jewel Rosary of the Profound Five-Fold Path by Kunga Rinchen, the Dharma heir to Jigten Sumgön. It begins with instructions on ngondro followed by a special set of preliminary practices focused on generating love, compassion, and bodhichitta. It then goes into the main practices of deity yoga, meditation on the guru as the four kayas, meditation on Mahamudra and the view, and the pith instructions on the nature of mind.

Garland of Mahamudra Practices

$19.95 - Paperback

By: Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche & Katherine Manchester Rogers

$22.95 - Paperback

By: Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche & Victoria Huckenpahler

Khenchen Konchog Gyaltsen has also translated Gampopa's Jewel Ornament of Liberation, which is a core text across all Dakpo Kagyu traditions.

The Jewel Ornament of Liberation

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Khenmo Trinlay Chodron & Gampopa & Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche

Classic Kagyu Texts

Though specific to the Drukpa Kagyu tradition, The Third Khamtrul Rinpoche references Jigten Sumgön throughout his extraordinary text The Royal Seal of Mahamudra, Volume One: A Guidebook for the Realization of Coemergence. Both volume one and two are excellent resources for the meditative approach according to the Kagyu tradition.

Other Influences and Mentions of the Drikung Kagyu Tradition

There are also two works on the practice tradition of the Six Yogas of Naropa with an emphasis on the Gelug tradition. These works both highlight the centrality of the Drikung Kagyu lineage in the transmission of these practices to Tsongkhapa: The Six Yogas of Naropa: Tsongkhapa's Commentary and The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa.

In Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche's autobiography Brilliant Moon, the Drikung Kagyu tradition comes up several times. The first is when he was young and staying in Draktsa, he had a vision of what he thought was Tseringma, which he attributed to the long presence of disciples of the Gyalwa Drikungpa (Jigten Sumgön) staying there in archaic times. Later, His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche became his student and he taught him extensively, including spending two months imparting the Treasury of Precious Instructions.

$39.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche & Ani Jinba Palmo & Shechen Rabjam

Many other works discuss the Drikung Kagyu tradition and quote from its lineage holders, including:

- Buddhist Fasting Practice: The Nyungne Method of Thousand-Armed Chenrezig

- Strand of Jewels: My Teachers’ Essential Guidance on Dzogchen

- The Nectar of Manjushri's Speech: A Detailed Commentary on Shantideva's Way of the Bodhisattva

- Lion of Siddhas: The Life and Teachings of Padampa Sangye

- Born in Lhasa: The Autobiography of Namgyal Lhamo Taklha

- The Dalai Lama's The Gelug/Kagyu Tradition of Mahamudra

- The Life of Shabkar: The Autobiography of a Tibetan Yogin

Additionally, we have over two dozen articles from the Snow Lion newsletter archive that are Drikung Kagyu specific. Please explore! Also check out our topic page on the Drikung Kagyu Tradition.

Another excellent resource is drikung.org, which contains information on many of the teachers and events in the Drikung Kagyu tradition, including the 800th parinirvana anniversary celebration of Jigten Sumgön, which will be held in October 2017 in Dehra Dun, India, and will be presided over by His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche.

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

Mahamudra: Meditation Directly on Reality Itself

Tilopa and the Attainment of Non-Attainment

Once, Tilopa advised his disciple to go off to an isolated retreat and avoid any meditation.

Now, this may seem a little unusual for a meditation retreat. He explains, however, that when you go to meditate, you normally take up something to meditate on, some thing. That thing, and therefore that meditation, is necessarily artificial.

The practice of Mahamudra is not like that at all. It is not taking up a thing called Mahamudra and meditating on it. Ultimately, Mahamudra practice is meditation directly on reality itself.

the nature of reality is beyond the illusion of the phenomenal world, the world as it appears.

Reality itself is not something devised or made up. What you have to do here is accustom yourself to that, practice that.

You are not taking up a meditation, but rather are practicing something. Like any activity, when you practice and become accustomed to it, it becomes easier and easier. So, acquaint yourself with this lack of anything whatsoever to be taken up as a discrete object.

Focus on reality itself and become accustomed to that. Tilopa’s advice, then, is that if you attain something by this Mahamudra practice, then you have not attained Mahamudra. Attaining Mahamudra is attaining non-attainment. If you are not getting anything, then you’re getting Mahamudra. If you get some thing, then necessarily it is not Mahamudra.

What does it mean to attain non-attachment?

What is the meaning of this? If, when we strive for Buddhahood, we think that Buddhahood is something that we are going to get, we will be making a great mistake.

We would be like hunters going after an animal. Buddhahood would be reduced to just another worldly activity in which we engage to get some pleasure for ourselves.

Mahamudra is not like that, it is not some thing to be obtained. It is attaining the state of non-attainment. Understanding that, we do not focus on obtaining something but on transcending. We have to get beyond that search for something to grasp onto.

Mahamudra. . . . is not some thing to be obtained. It is attaining the state of non-attainment. Understanding that, we do not focus on obtaining something but on transcending.

Now the nature of reality is beyond the illusion of the phenomenal world, the world as it appears. What appears is illusory; reality is something else. So, when engaging in this meditation on Mahamudra, one seeks to realize Mahamudra. As long as it is something that is an object of mind, something that is conceived by mind, then is it necessarily something other than Mahamudra.

Mahamudra is not a conception, not something which is of the nature of appearances or of the nature of objects of the conventional mind.

Tilopa’s advice is that if the disciple wishes to see Mahamudra, the disciple must go beyond conventional mind and abandon worldly involvement, because the conventional mind and worldly activities are what obscure the realization of Mahamudra and can never lead to it.

Therefore, whatever we look for, whatever we try to hold on to in terms of objects of mind, is not going to be Mahamudra. It is something other than that.

It is not of the nature of the phenomenal world in any sense. As long as we conceive of it as something, we are making a mistake and will not attain the realization of Mahamudra in that way.

Tilopa’s advice is that if the disciple wishes to see Mahamudra, the disciple must go beyond conventional mind and abandon worldly involvement, because the conventional mind and worldly activities are what obscure the realization of Mahamudra and can never lead to it.

—excerpted from The Practice of Mahamudra

His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche is the thirty-seventh Drikung Kyabgon head of the Drikung Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism. He has worked tirelessly to renew and spread its scholarly and meditative traditions in many countries, including the United States. He lives at the seat of the Drikung Kagyu order in Dehra Dun, India.

For more information:

Click link for more Books, Videos, Articles, Events and Online Courses on Mahamudra.

Related Books

$27.95 - Paperback

By: Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche & Khenmo Trinlay Chodron & Robert Clark

$59.95 - Hardcover

By: Elizabeth M. Callahan & Takpo Tashi Namgyal & Dakpo Tashi Namgyal

$59.95 - Hardcover

By: Elizabeth M. Callahan & Takpo Tashi Namgyal & Dakpo Tashi Namgyal

$34.95 - Paperback

By: Rosemarie Fuchs & Asanga & Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye & Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso & Maitreya

His Holiness Drikung Chetsang Rinpoche on Body Posture

How we sit, stand, and hold our body affects our mind—which is of importance especially during meditation. This excerpt from The Practice of Mahamudra by Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche concisely describes the subtle effects of placements of the hands, tongue, and so forth.

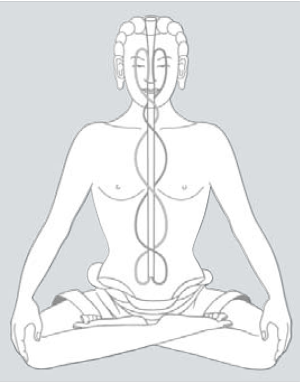

"It is very important to know what to do with the body while engaging in various types of meditation. First, there is the teaching on the sevenfold posture of Buddha Vairochana. The first of the seven aspects is the placement of the legs. In this posture, the legs are crossed in the lotus position, also called the vajra position. This position has many benefits. The benefit discussed in this context is that of redirecting one of the five winds. There are five main winds in the body. One is called the downward-clearing wind. Normally this wind is involved in all of the processes of evacuating things from the body, like the bowels, the urine, and so forth. It is responsible for anything that is pushed downward and out the lower orifices.

Regarding its function for the mind, it is engaged in the activity of the kleshas (poisons): greed, hatred, ignorance, jealousy, and pride. Of these five, the downward-clearing wind is most connected with the klesha of jealousy. Placing the legs in the vajra position inhibits, or blocks, the function of jealousy and in general redirects the force of the downward-clearing wind to the central channel, thereby clarifying mind and inhibiting the klesha of jealousy.

Next, the hands are folded together, palm upward, right on top of the left. The thumbs are held over the palms. The position of the right palm should be four finger-widths below the navel. This hand position redirects the force of the wind which is associated with the water element. By inhibiting its movement, by redirecting it to the central channel, the klesha of anger is inhibited.

Next, the spine is set very straight, not leaning one way or the other, forward or back, but completely straight up and down. You should visualize it as a stack of coins one on top of the other, all the way up the length of the spine such that it would fall over if it leaned one way or the other. The shoulders should be held back a bit, opening up the chest. This is said to be like a soaring bird with its wings stretched back, but don’t hold them too far back, just a little. Another way to think of this posture is that you are holding your chest out ward and shoulders slightly back. This causes the wind associated with the earth element to enter the central channel, thereby inhibiting the klesha of delusion.

The chin is held slightly downward and the tongue is held up towards the palate near the base of the upper front teeth. The teeth are held slightly open so air can pass between the upper and lower teeth, so don’t clench the jaw. All of this influences the wind associated with the fire element, causing it to enter the central channel and inhibit the klesha of desire.

The eyes should be generally directed at a spot four finger-widths in front of the tip of the nose and slightly down ward. Gently, softly focus at that spot about an arm’s length in front of your nose. The eyes should not be wide open, just gently look in that direction. This influences the wind associated with the space element, causing it to enter the central channel and inhibit the klesha of pride.

This position of the body is very important because the channels within the body will follow the external disposition of the body. The way the body is placed will set the channels; and the winds, of course, flow inside the channels, so if they are properly set, the winds will flow properly. Mind follows the wind. To focus the mind properly, the winds must also be functioning properly.

The closest association between the mind and the winds comes through the eyes. The focus, or disposition, of the eyes is influenced by the winds, which in turn influence mind, so it is very important how the eyes are focused. For the beginner, it’s easiest for the gaze to be directed somewhat downward and in front of you. A more advanced practice takes place with the eyes focused more straight ahead, and some highly advanced practices involve looking somewhat upward. There is also an association between the various practices and various goals or attainments. The manifestation body, nirmanakaya, is associated with the gaze directed downward, sambhogakaya straight ahead, and dharmakaya with the gaze directed slightly upward. The direction and focus of the eyes is important depending on one’s disposition and the relative predominance of the elements.

The four elements are of different strengths in different individuals. Some individuals are said to have a relatively greater amount of the earth element, for instance. Such a person will tend to relax and easily fall asleep, get drowsy very easily. For that type of person, it’s good to focus the eyes somewhat upward which will help keep them from falling into lethargy and sleep. Others, whose minds are constantly disturbed by random thoughts or excited thoughts, should look downward to help gain control over that process."

Books from the Drikung Kagyu Tradition

| The following article is from the Summer, 1999 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Mahamudra represents the highest level of teaching within Tibetan Buddhism. Its study and practice leads to the realization of the very nature of reality itself—there is not a single phenomenon which is not subsumed within the realizations of Mahamudra.

In 1994, H.H. Chetsang Rinpoche toured the USA and gave detailed instructions in Mahamudra methods based on the ancient traditions of Tibet and India. He carefully explained each of the five stages of Mahamudra and taught many meditation practices. His Holiness also gave precise instructions on meditative posture and breathing and responded with helpful answers to student's questions using the teachings of Tilopa and Gampopa to illustrate various points.

This book is a record of His Holiness' teachings on Mahamudra, and is the clearest presentation of Mahamudra meditation practice available.

His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche was born in 1946 in Lhasa, Tibet into the well-known Tsarong family. In 1949, he was recognized as the 37th Drikung Kyabgon, head of the Drikung Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism. He has worked tirelessly to renew and spread its academic and meditative traditions in many countries including the USA.

Following is an excerpt from The Practice of Mahamudra.

Snow Lion Publications, 1999 Edition, Ithaca, NY USA

The Attainment of Non-attainment

Once, Tilopa advised his disciple to go off to an isolated retreat and avoid any meditation. Now, this may seem a little unusual for a meditation retreat. He explains, however, that when you go to meditate, you normally take up something to meditate on, some thing. That thing, and therefore that meditation, is necessarily artificial. The practice of Mahamudra is not like that at all. It is not taking up a thing called Mahamudra and meditating on it. Ultimately, Mahamudra practice is meditation directly on reality itself.

there is not a single phenomenon which is not subsumed within the realizations of Mahamudra... Ultimately, Mahamudra practice is meditation directly on reality itself.

Reality itself is not something devised or made up. What you have to do here is accustom yourself to that, practice that. You are not taking up a meditation, but rather are practicing something. Like any activity, when you practice and become accustomed to it, it becomes easier and easier. So, acquaint yourself with this lack of anything whatsoever to be taken up as a discrete object.

Focus on reality itself and become accustomed to that. Tilopa's advice, then, is that if you attain something by this Mahamudra practice, then you have not attained Mahamudra. Attaining Mahamudra is attaining non-attainment. If you are not getting anything, then you're getting Mahamudra. If you get some thing, then necessarily it is not Mahamudra.

Attaining Mahamudra is attaining non-attainment. If you are not getting anything, then you're getting Mahamudra.

What is the meaning of this? If, when we strive for Buddhahood, we think that Buddhahood is something that we are going to get, we will be making a great mistake. We would be like hunters going after an animal. Buddhahood would be reduced to just another worldly activity in which we engage to get some pleasure for ourselves.

Mahamudra is not like that, it is not some thing to be obtained. It is attaining the state of non-attainment. Understanding that, we do not focus on obtaining something but on transcending. We have to get beyond that search for something to grasp onto.

Now the nature of reality is beyond the illusion of the phenomenal world, the world as it appears. What appears is illusory; reality is something else. So, when engaging in this meditation on Mahamudra, one seeks to realize Mahamudra. As long as it is something that is an object of mind, something that is conceived by mind, then is it necessarily something other than Mahamudra.

Mahamudra is not a conception, not something which is of the nature of appearances or of the nature of objects of the conventional mind.

the nature of reality is beyond the illusion of the phenomenal world, the world as it appears.

Therefore, whatever we look for, whatever we try to hold on to in terms of objects of mind, is not going to be Mahamudra. It is something other than that. It is not of the nature of the phenomenal world in any sense. As long as we conceive of it as something, we are making a mistake and will not attain the realization of Mahamudra in that way.

Tilopa's advice is that if the disciple wishes to see Mahamudra, the disciple must go beyond conventional mind and abandon worldly involvement, because the conventional mind and worldly activities are what obscure the realization of Mahamudra and can never lead to it.

Search, then, for mind itself.

Search for the perceiver or the meditator, the essential nature of the one who is seeking the realization.

Turn your search inward and seek mind itself.

Abandon all the coverings of mind which are like clothing—all the things which are associated with it and which one thinks of in terms of what mind is.

All of these are like clothing, and the search is for the naked mind, the unclothed mind, mind in its very essential essence.

All of the conventional attributes of mind are just concepts, things we must transcend in order to penetrate to the very core of the essential mind itself. To see the nature of reality, to realize Mahamudra, it is necessary to abandon involvement in the world.

As long as we conceive of it as something, we are making a mistake

In practice, this actually means to get rid of inner involvements. Inner involvements are the kleshas, the unwholesome negative mental activities of desire, aversion, delusion, and so forth. These are what must be abandoned, or dispelled. The technique for dispelling these is the practice of shamatha.

The example given here is a pool of water. If you want to see the depths of the water, one must clear out the mud, the defilements, in the water that makes it impossible for you to see the bottom. So the kleshas—greed, hatred, delusion, and so forth—are like the mud that fills the pond. Until all that mud settles out, you cannot see the bottom. It is the practice of mental quiescence that allows all of these kleshas to cease.

Then with vipashyana, you can see through the clear water to the essential nature of reality. And so, the realization of Mahamudra is not the creation of something which was not there, nor is it the removal of something.

In other words, to realize Mahamudra you do not get rid of or abandon appearances; they are not what is obstructing the view. Appearances can be allowed to stand just as they are. Nor is there anything to be achieved or produced. There is nothing to be obtained from reality to realize Mahamudra. Rather, through the practice of mental quiescence, allow the disturbing tendencies to subside and then reality will appear by itself.

It is the practice of mental quiescence that allows all of these kleshas to cease... There is nothing to be obtained from reality to realize Mahamudra.

The realization of ultimate reality can be approached in various ways by developing insight through establishing the correct philosophical view.

With regard to the various inner and outer phenomena, one can gradually learn the right and the wrong in terms of the view and develop the realization of one thing after another. In this way, a realization can gradually build up. However, the most effective way is to get at the very root of delusion and cut it off. Once this is cut off, the trunk, the leaves, the stems, and the branches of the tree of illusion will wither and die. So rather than remove them one at a time, it's best to go right to the root of delusion.

The way this is done in practice is to look at the essential nature of mind. Once that has been realized in its true nature, the root of delusion is destroyed and all the delusions with regard to all other appearances of the world will cease.

The realities of the inner and outer worlds will be realized together. Through this process of realizing ultimate reality by looking at the essential nature of mind itself, the root of all delusion is destroyed and one sees reality, the inner and outer, as it actually is.

Once that has been realized in its true nature, the root of delusion is destroyed and all the delusions with regard to all other appearances of the world will cease.

In the process of doing this, one also removes all the defilements from beginningless time. In all of our past lifetimes—from countless ages ago—we have accumulated vast negative karma, incalculable non-virtuous activities and defilements. If we tried to apply antidotes to each of these and purify them one by one, it would be an interminable task. However, by cutting the root of delusion, we cut the root of all these defilements and remove them all at once. So the direct view, the direct realization of the ultimate truth of Mahamudra, in and of itself destroys all the defilements accumulated from beginningless time.

The practical instructions for engaging in the meditation leading to Mahamudra are given here from the very beginning of the path.

The priority at the beginning is to gain a sense of control whereby mind does not go this way and that, becoming attached to worldly appearances which make it impossible to progress in Mahamudra practice.

This is where the practices related to mental quiescence come into play. The techniques to achieve it are described here. The various meditation techniques, like concentrating on the breath, are explained. The point is not control so much as it is unifying the essence of mind with the breath as it comes in and goes out.

direct realization of the ultimate truth of Mahamudra, in and of itself destroys all the defilements accumulated from beginningless time.

This process can be compared to learning to drive a car. In the beginning, you have to learn how to steer in a rough sense so that the car stays on the road. Later you can drive efficiently and go to your destination. So, these things like the breathing and the focus of your gaze are the necessary controls. Once you gain proficiency in this, mind will settle down, and you can continue more efficiently in this path of meditation. By controlling the eyes and breath, mind itself comes under control.

Having gained control through these techniques, mind is then used to focus on mind itself. When mind focuses on mind itself, the kalpana arise, and these must be cleared away.

unifying the essence of mind with the breath... By controlling the eyes and breath, mind itself comes under control.

Before mind can perceive itself, you must abandon all conceptual ideas; these are not mind. This is said to be like trying to find the center of the sky. The sky in this sense means the vastness of empty space. If we look for something that we can call the center, we will not find anything. Or if we look for the end of space, we will also not find anything. The very nature of space is that it is endless, so finding the center or an edge is impossible.

Similarly, when we look at mind and try to find characteristics like that, we will not find them. These characteristics are conceptual, they are the dichotomies between center and edge, or size or shape or color. We must go beyond these dichotomies of thought in order to see mind in its essential nature.

Viewing the essential nature of mind is compared to viewing the ocean or the sky. If you look at the ocean superficially, your view is obscured by the waves on the surface. If you look at the sky, you just see clouds and not the sky. The waves on the ocean and the clouds in the sky are like the kalpana If we go beyond the waves, we see the depths of the ocean. If we go beyond the clouds, we see the extent of the sky. Likewise, we have to go beyond the kalpana to see the mind. They disappear just like the waves on the ocean and the clouds in the sky. They are not permanent or abiding in their nature. So, by seeing the true nature of mind, all of these kalpana simply dissolve and disappear.

through the practice of mental quiescence, allow the disturbing tendencies to subside and then reality will appear by itself.

Taking the example of the sky, we can see that even though things like clouds appear in the sky, when they disappear, they leave no trace. Colors appear in the sky—the whiteness of dawn and the darkness of midnight. The darkness does not leave a stain; when the sun rises in the morning, it's all gone. Likewise, the colors of the day; although they appear in the sky, they are gone at night without a trace. So the nature of the sky itself is undefiled, unmarked, unstained by that which appears within it. Its nature is that it is non-composed. It is not made up of parts. It is not something which we can define in terms of size, shape, color, or form.

So, like that, mind has various contents which appear in it but do not leave a residue. They just disappear. Mind is also not definable by way of size, shape, color, extent, or any characteristics like that. In its essential nature, mind is identical with the Tathagatagarbha, Buddha-nature. It is also the wisdom of self-knowledge. The wisdom of self-knowledge and Buddha-nature are by their most intrinsic, basic quality free of all attributions. By realizing their nature, all of these adventitious contents are dissolved.

Likewise, mind. Although it has been engaged for countless eons since beginningless time in all sorts of activities, accumulating all sorts of karma and defilements, its very nature is completely unstained by all these things.

The nature of the mind is also compared to space. In empty space, various things arise—various appearances, material objects, worlds, suns, moons. All of these things arise in space and stay there for a very long time, moving this way and that. All of the activities of the world take place in space. But then everything moves on and the space that was filled at one time is empty at another time. Once all of the things have moved on and are no longer present in a certain space, that space is completely empty and completely free of any residue of all that took place there.

Likewise, mind. Although it has been engaged for countless eons since beginningless time in all sorts of activities, accumulating all sorts of karma and defilements, its very nature is completely unstained by all these things. When one realizes the clear light of reality, then all those stains completely disappear, leaving no residue whatsoever in mind.

His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche, Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche, is the thirty-seventh Drikung Kyabgon head of the Drikung Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism. He has worked tirelessly to renew and spread its scholarly and meditative traditions in many countries, including the United States. He lives at the seat of the Drikung Kagyu order in Dehra Dun, India.

Related Materials:

Mahamudra Topic Page - Discover Books, Courses, Videos, Articles & Events

Books Related to Mahamudra

Khenchen Konchog Gyaltsen and the Drikung Kagyu Dharma Center

| The following article is from the Winter, 1986 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

The Drikung Kagyu Center is under the patronage of H.H. the Drikung Kyabgon, Chetsang Rinpoche. Its resident teacher is Khenpo Rinpoche, Konchog Gyaltsen, Abbot of all the Drikung Kagyu centers of North America. Khenpo was born in Tibet. After escaping the Chinese takeover Rinpoche received his Acharya degree and then studied for years with highly realized masters of the different lineages. He also did the traditional three year retreat during which time he studied the Five-fold Profound Path of Mahamudra, the Six Yogas of Naropa and other teachings. Khenpo is a very prolific writer as well as a popular teacher. His first two books are being published this fall by Snow Lion Publications. They are The Garland of Mahamudra Practices and Prayer Flags: Spiritual Teachings of Jigten Sumgon. The newest book being prepared for Snow Lion is entitled The Search For The Stainless Ambrosia. Rinpoche is a young man and speaks fluent English. The center offers a variety of classes and a regular meditation schedule. Open House is held once a month.

Presently Khenpo and members of the center are organizing the first American tour of H.H. the Drikung Kyabgon, Chetsang Rinpoche. His Holiness is one of the heads of the illustrious Drikung Kagyu lineage which traces back in an unbroken lineage through Jigten Sumgon, Pakmo Druba, Gampopa, Milarepa, Marpa, Naropa, and Tilopa to Vajradhara. When the Chinese communists took over Tibet the two Drikung Kyabgons, their Holinesses Chungtsang and Chungtsang Rinpoche, the leaders of the illustrious Drikung Kagyu lineage, were both inprisoned. H.H. Chungtsang was imprisoned by the Chinese Communists for ten years, after which he was assigned thirteen years' hard labor. He was released from prison in 1983. H.H. Chetsang Rinpoche after being imprisoned for twenty years escaped and fled to India. When he arrived in India thousands of monks gathered at Phiying Monastery in Ladakh where he established his seat-inexile. Great celebrations were held including lama dances, mandala offerings, and long-life offerings. His Holiness gave teachings and empowerments to the thousands who gathered there and also celebrated the 800th anniversary of the estaablishment of the first Drikung Kagyu Monastery by Lord Jigten Sumgon. During the anniversary celebration Khenpo Konchog Gyaltsen was appointed to the position of a Khenpo (Abbot) of the Kagyu order. Recently His Holiness Chetsang Rinpoche represented the Kagyu order at the great Kalachakra Initiation in Bodh Gaya, India where 250,000 Tibetans and Westerners gathered to receive the week-long initiation. This upcoming tour will be His Holiness' first trip to North America.

Khenpo Konchog Gyaltsen