Nagarjuna

Nagarjuna, the South Indian Buddhist master who lived six-hundred years after the Buddha, is undoubtedly the most important, influential, and widely studied Mahayana Buddhist philosopher.

Nagarjuna

-

Nagarjuna's Seventy Stanzas$27.95- Paperback

Nagarjuna's Seventy Stanzas$27.95- PaperbackBy David Ross Komito

Translated by Tenzin Dorjee

Translated by Tenzin Dorjee

Translated by David Ross Komito

GUIDES

Indian Mahayana Masters of the 2nd-8th Centuries

The Indian Masters

Indian Mahayana Masters from the 2nd-8th Centuries

The Tibetan traditions all look back to India as the source of wisdom. There were countless masters all over India, north and south, east (including present-day Bangladesh) and west (including present-day Pakistan). The Mahayana reached its full expression during this period, and what follows is a partial but growing list of Reader Guides to these masters.

The Seventeen Pandits of Nalanda

2nd through 11th centuries

Tibetan Buddhism is none other than the Buddhism of India in the tradition of Nalanda, the great center of Buddhist learning that was located in present-day Bihar, India. There are seventeen great scholars profiled here, including Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Asanga, Vasabandhu, Buddhapalita, Dignaga, Bhavaviveka, Vimuktisena, Chandrakirti, Dharmakirti, Shantideva, Shantarakshita, Kamalashila, Haribhadra, Gunaprabha, Shakyaprabha. and Atisha.

Nagarjuna

(2nd century....and beyond)

The great master closely associated with the Perfection of Wisdom

Shantideva and the Way of the Bodhisattva

8th century

The great master Shantideva is the author of two very important texts. The first is the Śikṣāsamuccaya, or Training Anthology which is a compilation of many works. The second is the Bodhicharyavatara, or Way of the Bodhisattva. This Reader Guide focuses on the latter work.

Asanga

4th century

The great Mahayana figure who is a key explicator of Yogacara, and also received the Five Maitreya texts from Maitreya.

Xuanzang (602-664 CE)

7th century

While not an Indian master, we wanted to include Xuanzang, certainly one of the most important figures in Buddhist history. His 16 year pilgrimage from his home in China throughout the Buddhist world is almost The Odyssey of the Buddhist literature. His translation and preservation of texts, as well as the account of his journey, had come down to us through the ages and is well worth a deep exploration.

The Thirteen Core Indian Buddhist Texts: A Reader's Guide

There are thirteen classics of Indian Mahayana philosophy, still used in Tibetan centers of education throughout Asia and beyond, particularly the Nyngma tradition, with overlap with the others. They cover the subjects of vinaya, abhidharma, Yogacara, Madhyamika, and the path of the Bodhisattva. They are some of the most frequently quoted texts found in works written from centuries ago to today. Below is a reader's guide to these works.

Khenpo Shenga, who penned influential commentaries on all 13 texts.

1. Pratimokṣha Sūtra

The first text is the Sutra for Individual Liberation or Sutra of the Discipline or Pratimokṣha Sūtra from the Buddha, containing all the precept for monastics. We have a commentary of the Bhiksuni Pratimoksha Sutra, Choosing Simplicity.

Related Books

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Thubten Chodron & Bhikshuni Jendy & Venerable Bhikshuni Master Wu Yin

2. The Vinayasutra by Gunaprabha

The second text is the Vinayasutra by Gunaprabha (7th century) who was a student of Vasubandhu. According to Ringu Tulku's The Ri-me Philosopy of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great, "Vasubandhu had many great students, and four of them were considered to be better than himself; Gunaprabha was the one who was better in the Vinaya. Gunaprabha put the four sections of the Vinaya into the proper order, and condensed the seventeen topics of the Vinaya into a shorter format; this is called the Vinaya Root Discourse. He wrote another text called the Discourse of One Hundred Actions, which gives practical instructions on activities related to the Vinaya."

3. The Compendium of Abhidharma or the Abhidharmasamuccaya by Asanga

This work on abhidharma does exist in a full, if somewhat dated English translation by Walpola Rahula. There is an excellent commentary on it by Traleg Rinpoche, published by KTD, Asangha's Abhidharmasamuccaya.

4. The Abhidharmakosha by Vasubandhu

Vasubhandu's Abhidharmakosha is the Hinayana treatise on abhidharma and is translated in Jewels from the Treasury which also includes the commentary by the Ninth Karmapa, Wangchuk Dorje.

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Thubten Chodron & Bhikshuni Jendy & Venerable Bhikshuni Master Wu Yin

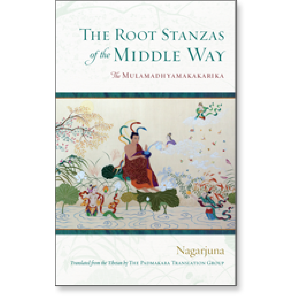

5. The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way or Mulamadhyamakakarika

Nagarjuna most famous work, The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way or Mulamadhyamaka-karika is the first work on Madhyamyaka. The Root Stanzas holds an honored place in all branches of Tibetan Buddhism, as well as in the Buddhist traditions found in China, Japan, and Korea, because of the way it develops the seminal view of emptiness (shunyata), which is crucial to understanding Mahayana Buddhism and central to its practice.

The latest translation of the text, by the esteemed team of the Padmakara Translation Group, translated this for the occasion of His Holiness the Dalai Lama's visit to Dordogne, France. This version includes the Tibetan text.

In a concise presentation of this, its translator said, "It is important to see that in his explanations, or rather presentations, of the Middle Way, Nāgārjuna is formulating neither a religious doctrine nor a philosophical theory. He is not giving us yet another description of the world. He simply points to phenomena—the things of our experience that appear so vividly and function so effectively—and shows by force of reasoned argument that they cannot possibly exist in the way that they appear to exist, and that, in truth, they can be said neither to exist nor not to exist. Existence and nonexistence, however, form a perfect dichotomy. And since phenomena are said to lie in neither of these two ontological extremes, we are forced to the conclusion that their nature is ineffable. It cannot be spoken of or even conceived of. And yet it cannot be nothing—for how can anyone possibly deny the vivid experience of the phenomenal world? And thus we come to the nub of the question: How is the true nature of phenomena to be understood? How are we to lay hold of, or rather enter into, the kind of wisdom that, by revealing the emptiness of phenomena, is alone able to uproot our clinging to their apparent reality and thereby dissipate the tyrannical power that they have over us?"

The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way

$29.95 - Hardcover

By: Christine Downing & Heinrich Dumoulin & Nagarjuna & Padmakara Translation Group

6. The Introduction to the Middle Way or Madhyamakavatara

Chandrakirti's Introduction to the Middle Wayor Madhyamakavatara. This book includes a verse translation of the Madhyamakavatara by the renowned seventh-century Indian master Chandrakirti, an extremely influential text of Mahayana Buddhism, followed by an exhaustive logical explanation of its meaning by the modern Tibetan master Jamgön Mipham, composed approximately twelve centuries later. Chandrakirti's work is an introduction to the Madhyamika teachings of Nāgārjuna, which are themselves a systematization of the Prajnaparamita, or "Perfection of Wisdom" literature, the sutras on the crucial, but elusive concept of emptiness.

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group

7. The Four Hundred Stanzas or Chatuḥshataka Shastra

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzasor Chatuḥshataka shastra was written to explain how, according to Nāgārjuna, the practice of the stages of yogic deeds enables those with Mahayana motivation to attain Buddhahood. Both Nāgārjuna and Aryadeva urge those who want to understand reality to induce direct experience of ultimate truth through philosophic inquiry and reasoning.

Aryadeva's text is more than a commentary on Nāgārjuna's Treatise on the Middle Way because it also explains the extensive paths associated with conventional truths. The Four Hundred Stanzas is one of the fundamental works of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, and Gyel-tsap Je's commentary is arguably the most complete and important of the Tibetan commentaries on it.

Mahayana practitioners must eliminate not only obstructions to liberation, but also obstructions to the perfect knowledge of all phenomena. This requires a powerful understanding of selflessness, coupled with a vast accumulation of merit, or positive energy, resulting from the kind of love, compassion, and altruistic intention cultivated by bodhisattvas. The first half of the text focuses on the development of merit by showing how to correct distorted ideas about conventional reality and how to overcome disturbing emotions. The second half explains the nature of ultimate reality that all phenomena are empty of intrinsic existence. Gyel-tsap's commentary on Aryadeva's text takes the form of a lively dialogue that uses the words of Aryadeva to answer hypothetical and actual assertions questions and objections. Geshe Sonam Rinchen has provided additional commentary to the sections on conventional reality, elucidating their relevance for contemporary life.

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Aryadeva & Gyel-tsap & Geshe Sonam Rinchen

8. The Way of the Bodhisattva or Bodhicharyavatara

The Bodhicharyavatara, or The Way of the Bodhisattva, composed by the eighth-century Indian master Shantideva, has occupied an important place in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition throughout its history. It is a guide to cultivating the mind of enlightenment through generating the qualities of love, compassion, generosity, and patience.

We have a lot of resources on this site for this text - you can start with Way of the Bodhisattva Resource Page. In particular, we strongly recommend watching the immersive workshop from May of 2016 with esteemed translator Wulstan Fletcher who is part of the Padmakara Translation Group.

In addition, we have the famous commentary on this text, The Nectar of Manjusri's Speech. In this commentary, Kunzang Pelden has compiled the pith instructions of his teacher Patrul Rinpoche, the celebrated author of The Words of My Perfect Teacher.

$21.95 - Paperback

By: Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche & Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal & Patrul Rinpoche & Khenchen Palden Sherab

A Guide to The Words of My Perfect Teacher

$34.95 - Paperback

The Five Maitreya Texts

And then there are the five Maitreya texts that he imparted to Asanga. For an explanation of these texts see two of the foremost translators of them explain them in this pair of interviews with Karl Brunnnholzl and Thomas Doctor.

9. The Ornament of Clear Realization or Abhisamayalankara

The Abhisamayalamkara summarizes all the topics in the vast body of the Prajnaparamita Sutras. Resembling a zip-file, it comes to life only through its Indian and Tibetan commentaries. Together, these texts not only discuss the "hidden meaning" of the Prajnaparamita Sutras—the paths and bhumis of sravakas, pratyekabuddhas, and bodhisattvas—but also serve as contemplative manuals for the explicit topic of these sutras—emptiness—and how it is to be understood on the progressive levels of realization of bodhisattvas. Thus these texts describe what happens in the mind of a bodhisattva who meditates on emptiness, making it a living experience from the beginner's stage up through buddhahood.

Gone Beyondcontains the first in-depth study of the Abhisamayalamkara (the text studied most extensively in higher Tibetan Buddhist education) and its commentaries in the Kagyu School. This study (in two volumes) includes translations of Maitreya's famous text and its commentary by the Fifth Shamarpa Goncho Yenla (the first translation ever of a complete commentary on the Abhisamayalamkara into English), which are supplemented by extensive excerpts from the commentaries by the Third, Seventh, and Eighth Karmapas and others. Thus it closes a long-standing gap in the modern scholarship on the Prajnaparamita Sutras and the literature on paths and bhumis in Mahayana Buddhism.

Groundless Pathstakes the same material and looks at in the context of the Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. This study consists mainly of translations of Maitreya's famous text and two commentaries on it by Patrul Rinpoche. These are supplemented by three short texts on the paths and bhumis by the same author, as well as extensive excerpts from commentaries by six other Nyingma masters, including Mipham Rinpoche. Thus this book helps close a long-standing gap in the modern scholarship on the prajñaparamita sutras and the literature on paths and bhumis in Mahayana Buddhism.

10. Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sūtras or Mahayanasutralankara

The Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sūtrasor Mahayanasutralankara

The Ornament provides a comprehensive description of the bodhisattva’s view, meditation, and enlightened activities. Bodhisattvas are beings who, out of vast love for all sentient beings, have dedicated themselves to the task of becoming fully awakened buddhas, capable of helping all beings in innumerable and vast ways to become enlightened themselves. To fully awaken requires practicing great generosity, patience, energy, discipline, concentration, and wisdom, and Maitreya’s text explains what these enlightened qualities are and how to develop them.

This volume includes commentaries by Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham, whose discussions illuminate the subtleties of the root text and provide valuable insight into how to practice the way of the bodhisattva. Drawing on the Indian masters Vasubandhu and, in particular, Sthiramati, Mipham explains the Ornament with eloquence and brilliant clarity. This commentary is among his most treasured works.

Ornament of the Great Vehicle Sutras

$69.95 - Hardcover

By: Dharmachakra Translation Committee & Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Maitreya & Khenpo Shenga

11. Middle beyond Extremes or the Madhyāntavibhāga

Middle Beyond Extremes contains a translation of the Buddhist masterpiece Distinguishing the Middle from Extremes. This famed text, often referred to by its Sanskrit title, Madhyāntavibhāga, is part of a collection known as the Five Maitreya Teachings. Maitreya, the Buddha’s regent, is held to have entrusted these profound and vast instructions to the master Asaṅga in the heavenly realm of Tuṣita.

$22.95 - Paperback

By: Dharmachakra Translation Committee & Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Ju Mipham & Maitreya & Khenpo Shenga

12. Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature -Dharmadharmatavibhanga

We have three works that explore this text.

Outlining the difference between appearance and reality, Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature shows that the path to awakening involves leaving behind the inaccurate and limiting beliefs we have about ourselves and the world around us and opening ourselves to the limitless potential of our true nature. By divesting the mind of confusion, the treatise explains, we see things as they actually are. This insight allows for the natural unfolding of compassion and wisdom. This volume includes commentaries by Khenpo Shenga and Ju Mipham, whose discussions illuminate the subtleties of the root text and provide valuable insight into the nature of reality and the process of awakening.

Mining Wisdom from Delusion

The introduction of the book discusses these two topics (fundamental change and non-conceptual wisdom) at length and shows how they are treated in a number of other Buddhist scriptures. The three translated commentaries, by Vasubandhu, the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, and Gö Lotsāwa, as well as excerpts from all other available commentaries on Maitreya’s text, put it in the larger context of the Indian Yogācāra School and further clarify its main themes. They also show how this text is not a mere scholarly document, but an essential foundation for practicing both the sūtrayāna and the vajrayāna and thus making what it describes a living experience. The book also discusses the remaining four of the five works of Maitreya, their transmission from India to Tibet, and various views about them in the Tibetan tradition.

Distinguishing Phenomena and Pure Beingwas composed by Maitreya during the golden age of Indian Buddhism. Mipham's commentary supports Maitreya's text in a detailed analysis of how ordinary, confused consciousness can be transformed into wisdom. Easy-to-follow instructions guide the reader through the profound meditation that gradually brings about this transformation.

Distinguishing Phenomena from Their Intrinsic Nature

$24.95 - Hardcover

By: Dharmachakra Translation Committee & Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Ju Mipham & Maitreya & Khenpo Shenga

Mining for Wisdom within Delusion

$39.95 - Hardcover

By: Coleman Barks & Karl Brunnholzl & Asanga & Maitreya & Mohammad Ali Jamnia & The Third Karmapa

Maitreya's Distinguishing Phenomena and Pure Being

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Asanga & Jamgon Mipham & Jim Scott

13. Treatise on the Sublime Continuum or the Uttaratantra Shastra

The Treatise on the Sublime Continuum or the Uttaratantra Shastra presents the Buddha's definitive teachings on how we should understand this ground of enlightenment and clarifies the nature and qualities of buddhahood. A major focus is “Buddha nature” (tathāgatagarbha), the innate potential in all living beings to become a fully awakened Buddha.

We have two books on this work.

The first is When the Clouds Part: The Uttaratantra and Its Meditative Tradition as a Bridge between Sutra and Tantra. This book discusses a wide range of topics connected with the notion of buddha nature as presented in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism and includes an overview of the sūtra sources of the tathāgatagarbha teachings and the different ways of explaining the meaning of this term. It includes new translations of the Maitreya treatise Mahāyānottaratantra (Ratnagotravibhāga), the primary Indian text on the subject, its Indian commentaries, and two (hitherto untranslated) commentaries from the Tibetan Kagyü tradition. Most important, the translator’s introduction investigates in detail the meditative tradition of using the Mahāyānottaratantra as a basis for Mahāmudrā instructions and the Shentong approach. This is supplemented by translations of a number of short Tibetan meditation manuals from the Kadampa, Kagyü, and Jonang schools that use the Mahāyānottaratantra as a work to contemplate and realize one’s own buddha nature.

The second title, Buddha Nature, includes commentaries by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye and Khenpo Tsultrim Gyatso.

$22.99 - eBook

By: Lenore Friedman & Rosemarie Fuchs & Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye & Keiko Matsui Gibson

And One More

As Georges Dreyfus notes in his The Sound of Two Hands Clapping, there is another core text that is often included in this group, for example at Namdroling: Shantarakshita's Adornment of the Middle Way including Mipham Rinpoche's commentary.

The Adornment of the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group & Shantarakshita

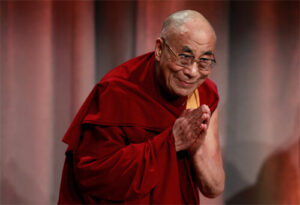

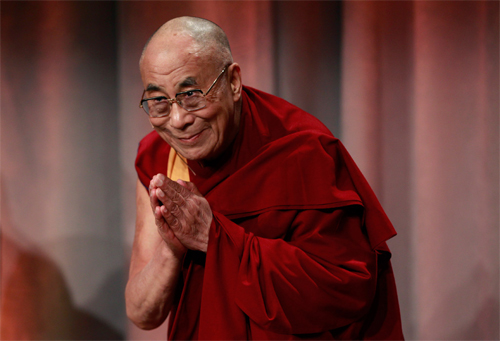

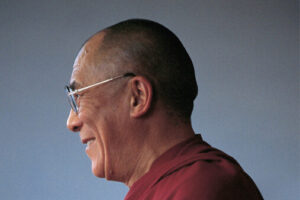

The Dalai Lama's Teaching on Stages of Meditation

His Holiness the Dalai Lama's visit to Boston

His Holiness the Dalai Lama gave an excellent teaching on Kamalashila's Stages of Meditation at MIT.

Below are the texts mentioned by His Holiness in his talk. For those interested in going deeper, you will find them complementary to the teaching:

- Stages of Meditation - A commentary on Kamalashila's work by the Dalai Lama

- Shantideva's Way of the Bodhisattva

- Aryadeva's 400 Stanzas of the Middle Way

- Nagarjuna's Letter to a Friend

You can also visit the Dalai Lama's website to learn more or click photos and videos to see footage from his events.

Related Books

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Aryadeva & Gyel-tsap & Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Nagarjuna's Letter to a Friend

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Kangyur Rinpoche & Longchen Yeshe Dorje, Kangyur Rinpoche & Nagarjuna & Padmakara Translation Group

The Seventeen Panditas of Indian Buddhism

His Holiness the Dalai Lama has often said that Tibetan Buddhism is none other than the Buddhism of India in the tradition of Nalanda, the great center of Buddhist learning that was located in present-day Bihar, India.

Many of the greatest masters and scholars in Indian Buddhism resided-and often presided-at this monastic center of learning which in its heyday included thousands of monks, dozens of temples and an enormous library. While we do not know with certainty that all of the seventeen masters below physically stayed at Nalanda, there is no doubt that their teachings and impact became fully integrated into the teachings and presentations of Buddhist thought there.

Traditionally, Tibetans have referred to the Six Ornaments of India (Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Asanga, Vasubandhu, Dignaga, and Dharmakirti) and the Two Supreme Ones (Gunaprabha and Shakyaprabha).

The categorization of seventeen described below was put together by His Holiness and expands upon these eight. While it does not include some of the great Nalanda masters whose genius still resounds in Buddhist teachings throughout the world - Naropa, for example - it is an important list of the brilliant scholar - adepts whose innovations in explaining the truth that the Buddha revealed continue to benefit us today.

These seventeen masters are vitally important because their writings are all based on real meditative experience. Their legacy of texts and teachings that came out of this experience forms the very backbone of understanding that is the basis for establishing present day practitioners with the correct view that enables us to make progress on - and complete - the path to enlightenment.

Our Great Master's Series is a guide to the works of each master, with a focus on what is available from Shambhala and Snow Lion Publications, though we will include important works that our friends at Wisdom Publications, KTD, and others are publishing.

The order below has been changed from how it has been presented elsewhere to that of a more chronological one, which interestingly reveals how these great minds were often contemporaneous with each other and focused on very different areas of thought in Buddhist philosophy.

1. Nagarjuna is considered the first of the seventeen panditas of Nalanda. While Western scholars generally assume there were two Nagarjunas separated by several centuries, received tradition holds him as a long-lived master who was critical in revealing the Mahayana teachings and sutras, elucidating the meaning of emptiness and the Madhyamaka view in particular, and being a great master of tantra. His works are typically divided into three groups: his praises, his speeches, and works on reasoning. His most famous text is from the latter category; entitled Treatise on the Middle Way, it is translated in The Ornament of Reason.

2. Aryadeva (3rd century) was Nagarjuna's student and while many Western scholars once again identify two, the Tibetan tradition identifies him as a single master, active in the third century CE. At Nalanda, he was famous for converting many followers of brahminism to the Buddhist view. He is also said to be identical with one of the 84 mahasiddhas, Karnari. He is most famous for his Four Hundred Stanzas of the Middle Way which is a commentary on Nagarjuna's Treatise on the Middle Way that explains the paths associated with conventional truths.

Aryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Aryadeva & Gyel-tsap & Geshe Sonam Rinchen

3. Asanga (320-390), born in present day Peshawar in Pakistan and the older brother of Vasubandu, he is often considered the father of Yogachara, though his texts cannot be so neatly categorized. While initially studying in the Sarvastivadin tradition, he adopted the view and practice of Mahayana. He spent 12 years in a cave, after which he had visions of Maitreya who brought him to Tushita heaven and gave him the teachings that form the five Maitreya texts. Other famous works include his commentary on Abhidharma from a Mahayana point of view as well as his Bodhisattva Paths and Bhumis and the Compendium of Mahayana.

4. Vasubandhu (4th century, possibly into the 5th), the brother of Asanga, is most famous for his Treasury of Abhidharma. Vasubandhu's classic short text on abhidharma, with commentary by Sthiramati has been translated by Artemus Engle in the book The Inner Science of Buddhist Practice: Vasubandhu's Summary of the Five Heaps with Commentary by Sthiramati, one of the most detailed presentations of mind and mental factors. He also presents Vasubandhu on Abhidharma in this short video discussing the skandhas, ayatanas, and dhatus, or in other words an explanation of what is presented in the Heart Sutra. Later, under the influence and guidance of Asanga, he adopted the view and practice of Mahayana.

5. Buddhapalita (470-540) is known as an early systematizer of what later writers termed the Prasangika Madhyamaka, which uses a technique of describing the absurd consequences of holding any view in an attempt to describe reality. While I am not aware of any complete translation of his works - which include a commentary on Nagaruna's Root Verses of the Middle Way - his ideas are succinctly encapsulated in the introduction of Introduction to the Middle Way.

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group

6. Dignaga (480-540) was a monk who was an early articulator of Buddhist logic, using syllogisms as a method for arriving at what he saw as the two types of valid cognition, that is, direct perception and inference. His most famous work is his Compendium of Valid Cognition and while a complete translation of this is not available in English, the ideas presented therein are explored in depth in Knowledge and Liberation and many other works.

7. Bhavaviveka (500-570 CE) is considered the godfather of what later writers term the Svatantrika Madhyamaka, in contrast to the Prasangika variant of which he was critical. His ideas are succinctly encapsulated in the introduction of Introduction to the Middle Way. While we are not aware of a complete English translation of this yet, his ideas are explored in depth in many works.

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group

8. Arya Vimuktisena (6th century), building on the work of Dignaga and later Madhyamaka teachers, wrote the first - and very important - commentary on the Ornament of Clear Realization (one of the Five Maitreya texts) that explicitly made the connection between it and the Perfection of Wisdom sutras. Link to video sharing: The Tibetan Commentaries on the Prajaparamita, Perfection of Wisdom.

9. Chandrakirti (600-650) built on the works of Nagarjuna and Buddhapalita, further elucidating them in his Introduction to the Middle Way. His work is the bedrock of the Prasangika viewpoint.

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group

10. Dharmakirti (600-670) built on the work of Dignaga and was a seminal figure in articulating what constitutes valid cognition. Dharmakirti argued that improvement of spiritual qualities were not limited by or to human nature. More can be read on this in the article Dharmakirti on Unlimited Spiritual Qualities. More can be read about Dharmakirti's theory of existance in the book Is Enlightenment Possible?: Dharmakirti and rGyal tshab rje on Knowledge, Rebirth, No-Self and Liberation by Roger Jackson, and by going to this published article.

11. Shantideva (8th century) is best known as the author of The Way of the Bodhisattva. For an article on Shantideva and his texts, see here.

12. Shantarakshita (725-788) was born into the royal house of Zahor in Bengal and became a great scholar at Nalanda who was later instrumental in establishing Buddhism in Tibet. His Adornment of the Middle Way is one of his more famous works. This work, later categorized as Yogachara Svatantrika Madhyamaka, builds on the work of his predecessors and presents what many consider to be one of the most important texts to study to receive the full and balanced understanding of how the various philosophical strains within Mahayana Buddhism coexist.

The Adornment of the Middle Way

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group & Shantarakshita

13. Kamalashila (740-795), a student of Shantarakshita, went to Tibet and was part of the great debate at Samye with Moheyan, a Chan master, in which Kamalashila is said to have debated and defeated him, though more about this episode is explained in our forthcoming Tibetan Zen: Discovering a Lost Tradition. His most famous works are three Stages of Meditation texts, some or all of them having been written in the wake of this famous debate. A translation based upon the middle section of the Bhavanakrabya by Kamalasila, is explained in the book Stages of Meditation: Training the Mind for Wisdom by H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Kamalashila.

14. Haribhadra (9th century), who lived around the same time as Kamalashila and was possibly a student of Shantarakshita, is best known for his commentaries on the Perfection of Wisdom (his is still the most used commentary for this subject in the Tibetan tradition) and the Ornament of Clear Realization. While complete English translations of his works are not yet available, his work is treated in depth in the Gone Beyond volumes on Prajaparamita and the Ornament of Clear Realization. His ideas are explored in depth in many works which will be covered in a subsequent post dedicated to him.

15. Gunaprabha (7th century) is most famous for his work on the vinaya in which he abridged the massive vinaya texts of the Mulasarvastivadins into a text, Vinayasutra, that remains the most important work on discipline in the Tibetan monastic traditions.

16. Shakyaprabha is another master revered for his work on vinaya. He and Gunaprabha are known in Tibet as the “Two Supreme Ones”.

17. Atisha (982-1054) was the great Bengali master who, after residing at Vikramashila and Nalanda, later went and studied with Serlingpa in what most assume to be Indonesia before coming to Tibet to reinvigorate Buddhism there after the so-called dark period. A great tantric master, Atisha is most famous for founding the Kadam lineage in Tibet emphasizing innovative techniques of Mahayana practice such as lojong or Mind Training and the lamrim or graduated stages of the path as elucidated in his classic Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment.

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

$19.95 - Paperback

By: Atisha & Geshe Sonam Rinchen & Ruth Sonam

On a final note, I'd like to direct you to a moving and beautiful prayer in homage to these seventeen panditas, composed by His Holiness the Dalai Lama and translated by Adam Pearcey. It is available online from Lotsawa House.

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

Stages of Meditation by Kamalashila and the Dalai Lama

| The following article is from the Winter, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

The following is an excerpt from the book's introduction.

In the words of the Superior Nagarjuna,

If you wish to attain the unsurpassed enlightenment

For yourself and the world,

The root is generation of an altruistic thought

That is stable and firm like a mountain,

An all-embracing compassion,

And a transcendent wisdom free of duality.

Those of us who desire happiness for others and ourselves temporarily and in the long term should be motivated to attain the omniscient state. Compassion, altruistic thought, and the perfect view are the fundamentals and lifeblood of the path to highest enlightenment. At this juncture, we have faith in the doctrine of Lord Buddha and have access to his teachings. We are free from the major obstacles and have met the contributory factors such that we can study the vast and profound aspects of Buddha's teaching, contemplate their contents, and meditate oh their meaning. We must therefore use all these opportunities so that we won't have cause for regret in the future and so that we don't prove unkind to ourselves. What Kadam Geshe Sang- puwa has said strikes at the central theme. This verse greatly moves me from the very heart:

Teaching and listening are proper when they are beneficial to the mind. Controlled and disciplined behavior is the sign of having heard teachings. Afflictions are reduced as a sign of meditation. A yogi is the one who understands reality.

What is the one and only purpose of Dharma teachings?

One thing that should be very clear is that Dharma teachings have only one purpose: to discipline the mind. Teachers should pay attention and see to it that their teachings benefit the minds of their students. Their instructions must be based upon their personal experience of understanding the Dharma students, too, should attend teachings with a desire to benefit their minds. They must make an all-out effort to control their undisciplined minds. I might therefore urge that we should be diligent in following the instructions of the great Kadampa Geshes. They have advised that there should be integration of the mind and Dharma. On the other hand, if knowledge and practice are treated as unrelated and distinct entities, then the training can prove ineffective. In the process of our spiritual practice, we must examine ourselves thoroughly and use Dharma as a mirror in which to see reflected the defects of our body, speech, and mind. Both the teacher and student must be motivated to benefit themselves and others through the practice of the teachings. As we find in the lam rim prayers:

Motivated by powerful compassion,

May I be able to expound the treasure of Buddhadharma,

Conveying it to new places

And places where it has degenerated.

The Buddha's doctrine is not something physical. Therefore, the restoration and spread of Buddhism depends on our inner spirit, or the continuum of our mind. When we are able to reduce the defects of the mind, its good qualities increase. Thus, effecting positive transformations is what the preservation and promotion of the Buddha's doctrine means. It is obvious that the doctrine is not a tangible entity, that it cannot be sold or bought in the marketplace or physically constructed. We should pay attention to the fundamentals, like the practice of the three trainings renunciation, the awakening mind of bodhichitta, and the wisdom realizing emptiness.

The responsibility for the preservation and furthering of Buddhist doctrine lies upon those of us who have faith in that doctrine; this in turn depends on our attraction to the Buddha and respect for him. If we don't do anything constructive and expect that others will, then obviously nothing is possible. The first step is to cultivate within our minds those positive qualities taught by the Buddha After properly disciplining our own minds, then we may hope to help discipline others' minds. The great Tsongkhapa has clearly stated that those who have not disciplined themselves have hardly any chance of disciplining others. Acharya Dharmakirti has taught this principle in very lucid terms:

When the technique is obscure [to you],

Explanation is naturally difficult.

Bodhisattvas with such an intention ultimately aim to attain the state of enlightenment. For this purpose, they engage in the practices of eliminating the disturbing emotions that afflict the mind. At the same time they endeavor to cultivate spiritual insights. It is by following such a process of eliminating negative qualities and cultivating positive ones that Bodhisattvas become capable of helping other sentient beings. The Commentary on (Dignaga's) Compendium of Valid Cognition also says:

The compassionate ones employ all means

To alleviate the miseries of beings.

How can we use the Buddha's teaching to generate virtues?

Therefore, those of us who believe in the Buddha's teachings should try our best to generate virtues. This is extremely important. It is especially relevant in this age when the Buddha's doctrine is degenerating. We Tibetans are making noise and criticizing the Chinese for the destruction they have caused in our country. But the important thing is that as followers of Buddhism we must diligently adhere to its principles. The teachings are only purposeful when we see the advantages of practicing, undertake the discipline, and effect positive transformations in our hearts. Listening to lectures on other subjects has a different purpose there we aim to gain ideas and information.

You might wonder what are the signs of a true Dharma practitioner. Practice should begin with the ethical discipline of abstaining from the ten non-virtuous actions. Every negativity of body, speech, and mind should be properly identified and its antidotes fully understood. With this basic knowledge, an individual should eliminate negative actions like stealing, lying, and so forth, and practice honesty, kindness, and other virtuous deeds. Ordained monks and nuns have to follow the rules of monastic discipline. These are meant to discipline the way one wears the monastic robes, communicates with others, and so forth. Even the manner of looking at other people and the correct ways of addressing other people are taught in the rules of monastic discipline.

The whole purpose of meditation is to lessen the deluded afflictions of our mind... a practitioner with prolonged familiarity with and meditation on selflessness eventually gains an understanding of reality.

What is the real test of a Dharma practitioner?

For a Dharma practitioner, one of the major challenges is to counter our disturbing emotions and finally free ourselves from them. The difficulty of this is due to the simple truth that disturbing emotions have from beginningless time caused us to suffer all kinds of miseries. If someone bullies us or an enemy persecutes us, then we raise a hue and cry. External enemies, however brutal they are, only affect us during one lifetime. They have no power to harm us beyond this life. On the other hand, disturbing emotions are our inner enemies and can definitely cause disaster in future lives. These are, in fact, our worst enemies.

The real test for a Dharma practitioner comes from this angle: if our disturbing emotions are reduced, then our practice has been effective. This is the main criterion in determining a true practitioner, regardless of how holy we appear externally. The whole purpose of meditation is to lessen the deluded afflictions of our mind and eventually eradicate them from their very roots. By learning and practicing the profound and vast aspects of the teaching, a practitioner with prolonged familiarity with and meditation on selflessness eventually gains an understanding of reality.

Related Books

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 1

$29.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Jeffrey Hopkins & Tsongkhapa

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 2

$29.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Jeffrey Hopkins & Tsongkhapa

The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume 3

$27.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Jeffrey Hopkins & Tsongkhapa

Kindness, Clarity, and Insight

$16.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Elizabeth S. Napper & Jeffrey Hopkins

| The following article is from the Spring, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Contributions to the Study of Buddhism and Tibet In Honor of Jeffrey Hopkins

This is a book offered in tribute to Jeffrey Hopkins by colleagues and former students. Jeffrey Hopkins has, in his sixty years, made profound and diverse contributions to the understanding of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism in the West. In his collaborations with the Dalai Lama, such as Kindness, Clarity, and Insight, and in books like Tibetan Arts of Love and Emptiness Yoga, Hopkins has reached out to the general reader, making the wisdom of Tibet accessible to every one. Yet there is never anything superficial about his work; his recent Emptiness in the Mind-Only School is a magisterial display of painstaking scholarly work.

Changing Minds contains essays that reflect the breadth and influence of Hopkins.

The following is an excerpt from the Editor's Introduction.

Twenty-five years ago I first met Jeffrey Hopkins as my instructor in a popular undergraduate course on Buddhist meditation at the University of Virginia. 1 liked the course and studied with him for almost thirteen yearsbecause of the way Hopkins presented Buddhist ideas. He did not posture as the authoritative curator of a mummified body of knowledge. He did not mystify the tradition and he certainly did not act as a missionary for it. On the other hand, he did not attempt to account for Buddhism in terms of any extrinsic academic ideology. Instead, Hopkins was interested in encountering Buddhist worldviews as living systems of human meaning; his classes were invitations to participate in that encoimter. They were based on his own meticulous translations of primary-source Tibetan or Sanskrit texts, sometimes produced in collaboration with Tibetan colleagues. The message that I got, from his teaching and his books, was: There are and long have been real people, whole communities and civilizations, for whom the ideas and texts we are now studying are profoundly important. We should show them the respect of taking their ideas seriously. That means finding out how far we can go in understanding how others make sense of the worldand seeing how our minds change in the process.

Hopkins presented Tibetan Buddhism as a living system of meaning in part by bringing to campus distinguished Tibetan scholars from the refugee communities of India. At that time, in the middle of the 1970s, this was something quite rare; most of my fellow undergraduates had heard the term Dalai Lama only as a Johnny Carson punch-line. Sometimes a monk would accompany Hopkins to class and speak to us in Tibetan, with Hopkins translating. Hopkins taught many undergraduate and graduate courses in this way while I was at the University of Virginia. There is no doubt that the presence of visiting Tibetan scholars on campus greatly enriched my education in the graduate Buddhist Studies program. Instead of having only Hopkins representing and mediating Tibetan Buddhism to us, we had continuing opportunities to work with scholars whose credentials to speak from within and on behalf of the tradition were unimpeachable. Some graduate students in the program likely developed, outside of class, spiritual connections with these lamas that were deeper and more important to them than their academic relationship with Hopkins.

That was not my experience; I was not drawn into the program mainly by the Tibetan scholars. After all, they could not speak English and only Hopkins and the more advanced graduate students could really question them directly. For me, the heart of the program was Hopkins. He had no superficial flash as a public speaker, but he had intellectual substance and passion. He conveyed his prodigious learning with an intensity that John Buescher conjures from the past in the opening article of this volume. Buescher gives us Hopkins at workguiding students through the complexities of Sanskrit syntax, teaching them how to pull from the tangle something that would change their minds:

It's the self of persons and of things

that we're looking for, Jeffrey said, as he pointed to Nagarj una's text in front of him. The tiling that seems to cover over them and make them a whole, single entity, assembling things out of their parts. We've got to take them apart to see it. Parsing the words of the text, then translating them, the operation became unexpectedly exacting. Sweat rolled down in tight, little streams under my shirt. We were unprepared for this drill, this scalpel. Jeffrey, however, proceeded on, laying bare our ignorance, peremptorily rejecting any uncertain or wrong answer. As he thundered his demand for the right answer, we searched for it. We desperately wished we could find it, some seat of the soul, some little treasure amid the remains of the words that now lay in pieces all about us.

Did these teaching methods leave room for students to challenge the tradition itself, to form their own critical evaluation of it? In my undergraduate courses with Hopkins, he seemed to regard it as satisfactory if a student could think through some of the complexities of Tibetan Buddhist doctrine. He certainly did not forbid etic analysis or independent critique, but he did little to encourage it. This might not seem ideal, but it did not strike me as so different from many other courses that I had taken, in Russian literature, Greek tragedy, or experimental psychology, for example. In each case, the premise was that there is a very complicated, very unfamiliar story to be told. The novice must expect to spend time on the ground of the storyteller, learning the story well and getting the details straight, before launching an idiosyncratic metanar- rative on what the story (in this case someone else's religion) is really about.

As a graduate student, my experience was that Hopkins wanted even demandedwork that was not only intimately grounded in the details of the tradition, but also had something to say, something useful or insightful. As I gained mastery of a research topic (and not before), he clearly expected more of me than a re-transmission of what learned lamas had said. For example, he told me that my seminar paper on the Abhisamayalamkara was boring because it simply reorganized information from the tradition. On another occasion, Hopkins asked me to present a paper in an interdepartmental colloquium series, assigning me a topic from the work of the Sa skya scholar sTag tshang. I decided on my own that I would instead give a psychoanalytic treatment of Tsong kha pa on the three principal aspects of the path. When he heard my talk, rather than being upset that I had presumed to offer an independent analysis, he was clearly pleased. The same was true when I submitted my dissertation; when I used various Western theories to give an independent account of the religiosity of dGe lugs scholasticism, Hopkins's criticisms were aimed only at strengthening my argument.

Hopkins's scholarship likewise evidences concern to avoid arrogant pseudo-objectivity on the one hand and naive adulation on the other. Hopkins has taken special pains to avoid the first of these extremes and has been more careful in that regard than some. By being open in his appreciation for some aspects of the traditions he studies, Hopkins has at times chosen to risk appearing to some as an academic front-man for religious dogma. In books such as Meditation on Emptiness and The Tantric Distinction, Buddhist thought-systems are not specimens to be dissected at arm's length. Instead, Hopkins recreates his encounter with another world of meaning, a very particular and intricate Asian Buddhist world which can never again be imagined as completely separate from our world. Describing his version of a methodological middle way, Hopkins writes that his aim is to evince a respect for the directions, goals, and horizons of the culture itself without swallowing an Asian tradition as if it had all the answers or...pretending to have a privileged position.

* * *

Don Lopez and Joe Wilson conceived that this book should come into being to honor Jeffrey Hopkins in his sixtieth year. At their suggestion and with the encouragement of Anne Klein, I undertook the project, soliciting contributions only from a close circle of Hopkins's friends, admirers, and former students. Then, with some assistance from Snow Lion and outside readers, I selected the articles in this volume for publication. As Paul Hackett shows in the closing article of this volume, Hopkins's research has covered a wide range of concerns, centering on dGe lugs scholarship but ranging far beyond it in several directions. A thin cross-section of that diversity is reflected in the scholarship here.

Describing his version I of a methodological middle way, Hopkins writes that his aim is to evince a respect for the directions, goals, and horizons of the culture itself without t swallowing an Asian tradition as if it had all the answers or... pretending to have a privileged position.

John Buescher opens our volume with an atmospheric and evocative real-life detective story. Caught in the act of teaching Madhyamika Buddhism, Hopkins appears as a philosophical sleuth on the trail of truth. Buescher then weaves into this portrait its unexpected resonances, years later, in a baffling international news-eventthe sudden appearance of a previously unknown dental relic of the Buddha.

The Madhyamika theme continues through the next two articles, by Guy Newland and Donald Lopez. My article is inspired in part by the efforts of Hopkins to describe the Madhyamika view for a general readership. I summarize some of the philosophical claims Tsong kha makes in Lam rim chen mo, reflecting in particular on the notion of conventional reality. Lopez's piece distills a careful synopsis of Tsong kha pa's treatment of the object of negation (dgag bya) in Madhyamika analysis. Then, based on his own new translations, he treats us to a riveting critique of this position by the brilliant twentieth-century iconoclast, dGe dun Chos phel.

Contributions by Dan Cozort and Elizabeth Napper keep the focus on Tsong kha pa and his Lam rim chen mo, but move away from Madhyamika Cozort provides a useful, clear, and detailed analysis of Tsong kha pa on the special dangers of anger, which is said to cut the roots of virtue. What, exactly, does this mean? How deep is the damage of anger? Cozort finds Tsong kha pa working with mixed success to explicate this doctrine and integrate it into his system. Like Cozort, Napper scrutinizes Lam rim chen mo in her contribution, Ethics as the Basis of a Tantric Tradition: Tsong kha pa and the Founding of the dGe lugs Order in Tibet. She lays out exactly how Tsong kha pa used his sources, subtly and skillfully reshaping grammar, nuance, and context in order to build a new and unique system of religious meaning. She concludes with some frank observations about the impact that the distinctive features of this system (such as its emphasis on monastic ethics) have had on the later tradition. Nap- per's impeccable work, synthesizing insights from many years of work with Lam rim chen mo and its sources, merits the appreciation of everyone who studies the dGe lugs order.

The next pair of articles shift our attention to the contemplative traditions of rDzogs chen and Mahamudra. Anne Klein takes us into the realm of Bon rDzogs chen poetry. Her original translations gracefully depict a natural, open awarenessunrecognized by ordinary personsin which reality is experienced as spontaneous and unbounded wholeness. She carefully explains who reads such poetry, to what end, and she compares the handling of contradiction and nonduality in Buddhist Madhyamika with that in Bon rDzogs chen. Roger Jackson then gives us an outstanding treatment of a little- known topic, the tradition of dGe lugs Mahamudra (phyag rgya chen po). As he notes, Mahamudra is more usually associated with meditative practices central to the bKa' brgyud tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. Questions about the role of and basis for a dGe lugs form of Mahamudra lead Jackson to broader insights about inter-sectarian connections.

As Hopkins suggests, our understanding of early dGe lugs has been much aided by recent advances in our grasp on the teachings of Shes rab rgyal mtshan and the Jo nang other emptiness doctrine. Here we offer two articles which touch on this issue, demonstrating how the self-empty vs. other-empty controversy set the stage for otherwise disparate debates. Displaying his formidable knowledge of Tibetan Perfection of Wisdom literature, Gareth Sparham shows how debates about the authorship and authority of key commentaries evolved within the context of controversy between dGe lugs and Jo nang views. Then, Joe Wilson gives us a generous and cogent explication of how and why the concept of a basis-of-all (alay- avijnana, kun gzhi rnam par shes pa) is subject to radically different constructions in the Jo nang and dGe lugs traditions.

While cross-cultural and comparative themes are touched upon in other contributions, Jose Cabezon and Harvey Aronson bring them into focus. Cabezon analyzes the structure and content of Tibetan colophons, looking for evidence of an implicit theory of authorship and literary production. Simplistic notions of authorship are quickly problema- tized by the multiple layers of productivity through which a book is generated. Cabezon has given us a unique and nuanced study, full of allusions to and connections with the conversations of Western literary theory. Such cross-cultural comparison arises from historical contact; in the case of Tibetan Buddhism, that contact includes the unprecedented phenomenon of large numbers of Westerners taking up Buddhist practices and striving to embody Buddhist virtues. Using object-relations theory and his own experience as a clinician, Harvey Aronson warns of the pathological pitfalls that may afflict the self-sacrificing American bodhisattva, but argues for a model of healthy altruism.

Our volume concludes with Paul Hackett's comprehensive survey of the published works of Jeffrey Hopkins. We are grateful to Hackett for an ambitious essay charting the range and depth of Hopkins's oeuvre. Inasmuch as Hopkins's recently published Emptiness in the Mind-Only School has been hailed by many as his best work ever, and inasmuch as it is the first of a tliree-volume series, Hackett's work will perhaps but serve as a starting point for future bibliographic analysis.

In sum, this volume is presented as a tribute to the work of Jeffrey Hopkins as a teacher and as a scholar. Paul Hackett has written eloquently of Hopkins's impact:

Most people who have pursued knowledge and learning would be hard pressed not to remember at least one teacher sometime, somewhere, who first inspired them and instilled in them a sense of value in learning. This ability, the capacity not only to convey meaning, but also to motivate remains an art which stands apart from mere erudition. For some, it comes naturally; for others it requires effort; though in each person who manages to master it, there is always evident an idiosyncratic artistry by which their knowledge and experience is conveyed. So it is with Jeffrey Hopkins, who has repeatedly demonstrated not only his depth of knowledge, but also his skill as a teacher and writer.

As we see in this volume, he has inspired and enlivened us in many different ways. So now we say: Thank you!

Meditations of a Tibetan Tantric Abbot

| The following article is from the Spring, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

The Main Practices of

the Mahayana Buddhist Path

by Kensur Lekden translated by Jeffrey Hopkins

This books presents with the intimate freshness of a personal teaching, the main practices of the Mahayana Buddhist path. It details the attitudes cultivated in meditation ranging from turning away from cyclic existence, to developing love and compassion for all beings, to the profound view of emptiness.

This is still about the best introduction available on the central topics of compassion and wisdom and, most especially, the philosophical and meditative synergy between them.

-Prof. Anne Klein

Love

Here is an excerpt from the first chapter, entitled Love.

I want to offer good luck and happiness to all of you who have assembled here today.

Because all humans are doers of deeds, the Buddhist system of practice has an explanation of how to act. You do deeds by identifying that which is to be practiced or taken in hand and that which is to be forsaken or discarded. The best of what is to be adopted is effort at the means of causing everyone to possess happiness and to be free from suffering. With respect to adopting the means of causing everyone, yourself and others, to possess happiness, there are three actions to be done: hearing, thinking, and meditating.

Hearing means that you yourself hear the explanation of another or look in a book and discover what is to be done in order to obtain happiness. What will you discover with respect to possessing happiness?

First you need to have the body of a human or a god. That body must be healthy and free from pain. Also, you must have the resources, clothing, food, shelter and so forth of a human or a god. You must have a long life and be able to achieve what you seek.

Since we need these, what do we do in order to get them? To obtain the body of a human or a god in the next birth, you must, during this lifetime, abandon the ten non-virtues and you must maintain the ten virtues. Having the body and resources of a god or a human is called high status; the lower types of cyclic existence are hell beings, hungry ghosts, and animals.

The main cause of high status within cyclic existence within the round of birth, aging, sickness and death is good ethics. Chandrakirti says in his Supplement to (Nagarjuna's) Treatise on the Middle, Other than ethics, there is no cause of high status. Therefore all of us living here in this world, in a former life whenever it was kept any of the ten virtues, and in dependence on that, we attained our present body and resources.

Can you determine whether your future life will be good or not?

In determining whether our future lives will be good or not, we should analyze whether our minds are presently adopting the practices that will bring about happiness. Our teacher, Shakyamuni Buddha, said, To determine what you did in the past, examine your present body. To determine what will exist in the future, examine your present mind. To determine whether or not your future will be good, you should analyze the mode of behavior of your mind. The life that we have now is an effect of what we did in the past.

The cause of the arising of excellent resources happiness and comfort is the giving of gifts. You should not steal, you should not be miserly. Also, so that in future lives there will not be a great deal of fighting, so that you will not be punished, so that disturbances of yourself and others will not arise, you need to cultivate patience in this lifetime.

Since in the future life you need good education and knowledge of how to act, in this lifetime you must make great effort at study at giving up what is to be abandoned and at assuming what is to be adopted. Then, in order that in future lives your mind will not be distracted, in this lifetime you must cultivate meditative stabilization, samadhi, and set your mind one-pointedly.

In your next lifetime you need to be intelligent and know what is to be adopted and what is to be discarded and in order to do that, in this lifetime you need to train in the wisdom knowing what is suitable and unsuitable and in the wisdom knowing what exists. You should engage in study and training.

If the causes of happiness are achieved, the effect is happiness. Those causes of happiness are giving, ethics, patience, effort, concentration, and wisdom. If in this life you engage in the causes of happiness the six perfections, the ten virtues, and so forth then in a future lifetime the effect will definitely appear; happiness definitely will arise.

It is necessary for you to form an understanding of the practice of hearing, of what hearing is and of what is to be heard. Then all the factors of thinking must be discovered in detail. Thinking means that you develop a conviction; for instance, you come to the decision that for the arising of happiness, the causes of happiness and virtue must be achieved.

Because you need to obtain the happy effects and the causes producing them, and because it is necessary for yourself and others to attain them, you must meditate. In this world there were nihilists who said that one should not meditate, doing only those activities that will bring about marvelous happiness, comfort, and prosperity in this lifetime. The nihilists said that one should gather possessions and clothing, and if one's body is sick, one should take medicine, that these activities were justified, but that nothing else was needed. Such a philosophy appeared in the world and with respect to it there is this Buddhist teaching: You need a job for your livelihood, you need to work for the sake of your country, for the sake of yourself and others, to set up factories, to plant fields; still you should act mainly for the sake of your future life, because you will not always remain in this lifetime. All persons will definitely die, and the time of death is indefinite. At the time of death, nothing helps except religious practice. This is how it is. Therefore, even though you need happiness and comfort in this life and even though it is necessary to strive for the sake of food and drink now, this lifetime is short. Our longest condition of life is our countless future lives. If you consider only this which you can see now and you do not consider all the future lives which you cannot see, you will incur immeasurable fault. You will harm yourself.

What are the reasons for this? This life will definitely end. There is not even a single person in the world who will remain without dying. At the time of death not even your parents, who have been very kind to you, will go with you. You must go alone. Even if you have family, children, brothers, sisters, friends good friends not even one of them can be taken along with you. It is like taking a hair out of butter; you must leave your own body as well as the place where you were lying down and go alone. Therefore you must act mainly for the welfare of future lives.

The wealth we have accumulated in this life, we cannot carry with us. The friends whom we have arranged around us, we cannot take with us. We cannot lead people with us, servants and so forth. What can be carried with us? We take with us only the predispositions of our actions; for this reason we must establish beneficial predispositions through accumulating virtues which are the causes of happiness in the future. Therefore we must hear, think, and meditate in this lifetime for the sake of future lifetimes.

If you do not accomplish the causes of happiness in this lifetime, you will not have anything at all to carry with you at the time of death. If you have accumulated non-virtues, predispositions will have been established in your mind for the arising of suffering. If you have accumulated virtues, you will have predispositions in your mind that give rise to happiness. It is like the body and its odor. Wherever the body goes, the odor goes with it. Just so, wherever the person goes, these causes which are the accumulations of virtue and non-virtue go with him or her. Therefore, in this lifetime hearing must be done, and if through thinking understanding develops, meditation which achieves happiness and the causes of happiness must be performed.

You should cultivate this thought in meditation, May happiness and the causes of happiness come to be possessed. Such meditation is of two types: meditation for your own welfare and meditation for other's welfare. If you cultivate in meditation the thought, May I possess happiness and the causes of happiness in the next and all succeeding lifetimes, there is only a little benefit. How do you meditate so that there is great benefit? You meditate taking cognizance of the welfare of all sentient beings, thinking, May all sentient beings throughout all of space, illustrated by my kind parents of this lifetime, possess happiness and the causes of happiness. If this meditation is done, the benefit is limitless, equal to space itself.

Our teacher, Shakyamuni Buddha, said, To determine what you did in the past, examine your present body. To determine what will exist in the future, examine your present mind.

What example is there for the benefit? In the word of Buddha, it is said that if a sesame seed is squeezed, only a little bit of oil comes out, but if many are squeezed, a huge barrel can be filled with the oil. Even if you meditate only once for only five minutes taking cognizance of all sentient beings, thinking, May all sentient beings throughout space and illustrated by my kind parents of this lifetime have happiness and the causes of happiness, then, even though there is only a little bit of help with respect to each sentient being and even though you meditate for only five minutes, because the scope is so vast, the virtue is inconceivable. If virtue had form, it would not fit in the whole world system. Virtue, however, is not physical; it is a product that is neither form nor consciousness. Virtues are latent predispositions abiding in the continuum of the mind.

Just as a little oil is taken from a single sesame seed, so with many it is possible to fill a pot with oil. In the same way, since sentient beings are limitless, if you meditate for the welfare of others, using this great field of awareness, wishing, May all sentient beings have happiness and the causes of happiness, the benefit from that one time is immeasurably great because it establishes very beneficial predispositions in the continuum of the mind.

Within our own country, do we not act lovingly toward our own children, our own friends? In just the same measure we are to act lovingly toward all sentient beings throughout all of space. Even if someone acts like an enemy toward us, we are to cultivate love toward that person. We should cultivate love not only when someone acts well toward us, but also when someone acts badly or in a middling manner toward us. To all of them we are one-pointedly, equally, to cultivate love.

The chief of all those activities you should assume is the cultivation of love the wish that all sentient beings have happiness and the causes of happiness. This helps you in the future; in addition, you should do whatever should be done in your own country. To say, I am doing religious practice, and not act in the service of your country is totally wrong.

Even if you die tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, you should meditate and study today. Why is this? Sakya Pandita said that even if one is soon to die, one should learn the sciences, that though one will not become wise in this lifetime, one is certain to in the next birth. Thus, even if you are to die tomorrow, you should study, learn, and meditate today.

There are many facets to meditation. You identify the causes of happiness, the ten virtues, the six perfections giving, ethics, patience, effort, concentration, and wisdom and then cultivate the wish that all sentient beings have these causes of happiness and happiness itself lives as gods and humans, resources, comfort, and so forth.

How can meditative posture help your meditation?

Using the posture of the Buddha Vairochana, the adamantine (lotus) or the half-adamantine posture

In an actual session of practice you need to assume a meditative posture and set the mind one-pointedly without distraction on the object of meditation. You should assume the sitting posture of the Buddha Vairochana, the adamantine (lotus) or the half-adamantine posture. Your eyes are not to look greatly upward nor are they to be shut, but are to be set evenly. If, except for looking at the point of the nose, you look to the right or to the left, the mind will be distracted. Your backbone must be straight, without bending backward or forward or to the right or to the left. Your shoulders must be set straight without bending this way or that. Your head must be set naturally without being arched back or without being bent forward; your nose should be in line with your navel. Your lips and your teeth should be set naturally and freely, and your tongue should be set at the back of your upper teeth. Your exhalation and inhalation of breath should not be noisy and should not be done with difficulty, but softly and gently. Allow the breath soundlessly and effortlessly to move in and out without purposefully making it slower or faster.

How to place the hands in meditative equipoise or like that of Avalokiteshvara

There are many different ways to place the hands, and you should do whatever suits you. There is one way with the hands on top of one another, the right hand on top of the left and placed in the center of the lap, called the position of meditative equipoise. There is one way where the left hand is placed flat on the lap with the palm upward and the right hand extends over the right knee touching the ground. This is called the posture of meditative equipoise touching the earth. Another posture is like that of Avalokiteshvara, for the sake of resting; you set the palms of your hands flat on the ground at your sides. For those who are cramped, this is quite comfortable. In some postures, one holds a sword or a book in a hand, but the posture of meditative equipoise is easier. If you are a little uncomfortable, sit in the posture of rest. It is very comfortable.

How to set the mind one-pointedly without distraction

When it is time to meditate and your posture has been set correctly, considering one exhalation and one inhalation of breath as one unit, count your breaths until twenty-one. This will prevent your mind from being distracted elsewhere; it will prevent your ears hearing sounds, your eyes seeing forms, your nose smelling odors, your tongue perceiving tastes, your body feeling touches. These will not occur. The mind will thereby be set one-pointedly without distraction. Now you should call to mind your acquaintances of this lifetime and cultivate in meditation the thought, May all sentient beings have happiness and the causes of happiness. This meditation is called the cultivation of love because you are being loving and beneficial toward all beings.

Initially, this is not to be meditated too long, just for ten or fifteen minutes, then more and more by degrees. After you have meditated this way for months or years, you can make it longer and longer. It is not good to become completely tired.

Cultivate the wish that all sentient beings have the causes of happiness

Once you have cultivated the thought, May all sentient beings possess happiness and the causes of happiness, and this meditation has been done for many, many years, then eventually you will attain what is called immeasurable love. When you have attained immeasurable love, you have meditative stabilization, meditative equipoise, and calm abiding.

You should leave aside a suitable length of time for meditation and cultivate love every day, continuously. You can meditate just before going to bed or early in the morning when you rise. If you cultivate love little by little, very clearly, then since the field of awareness is all sentient beings, sending love to all of them, it is as if you are repaying the immeasurable kindness that they extended to you in former lifetimes. When you meditate for the sake of the welfare of others, your meditation is included within the activities of a being of greatest capacity from among the three types of beings: those of small, middling and great capacity.

Now let us break for a short period and when you return to meditate, assume the posture that I have described, begin the breathing exercise, and when about to meditate, take to mind your own father and mother of this lifetime, then make the aspiring prayer, May all sentient beings throughout all of space, as illustrated by my own father and mother, have happiness and the causes of happiness. When you are about to leave the meditation you should dedicate it, thinking, By the fruit of whatever virtue has arisen from the force of my hearing and thinking and meditating, may all beings be freed from cyclic existence and attain the state of a perfect Buddha Or, it is sufficient to say at the time of dedication, May whatever virtue there is in having cultivated the thought, May all sentient beings have happiness and the causes of happiness,' help everyone throughout space.

What fault is there if you do not make a dedication? Even if you meditate well every day, when a little hatred arises, when someone pushes you and you immediately become angry, it is said that these virtues are destroyed. In the commentaries on Buddha's word, it is said that the virtue accumulated over a thousand eons is destroyed with one moment of anger.

When Shakyamuni Buddha was residing in Bodhgaya, he told 2,250 Hearers, Anger destroys the roots of virtue. The Hearers thought, If so, there is not one among us who does not get angry; thus none of our roots of virtue have remained. In the future none will remain. Even if we do virtue, it cannot be amassed. They were very worried. They thought, If one moment of anger can destroy the virtues accumulated over a thousand eons, then since we get angry many times every day, we do not have any virtue.

When they related this to Buddha, he poured water into a little vessel and asked, Will this water remain without evaporating? Because India is very hot, the Hearers thought, In a few days the water will evaporate. This must mean that our virtue will not remain at all. They were extremely worried. Then Buddha asked, If this water is poured in the ocean, how long will it stay? It will remain until the ocean itself evaporates.

Therefore, if you do not just leave this virtue, but dedicate it, making a prayer petition that it become a cause of help and happiness for limitless sentient beings, then until that actually occurs, the virtue will not be lost. Like a small amount of water poured into the ocean, which will last until the ocean itself dries up, so the fruit of your virtue will remain until it has ripened. The benefit of hearing, thinking and meditating, in terms of causing all persons to possess happiness and the causes of happiness, is inconceivable, but if it is not dedicated, then when anger arises, it will be destroyed. This benefit cannot be seen with the eye, but it is inconceivable.

You are amazingly virtuous. I only think that it is wrong for me to sit above you. I should sit below you. It is wonderful that you feel motivated to hear about this practice and meditate and cultivate it in meditation.

Now, rest a little and then when you return to meditate, sit as was explained before, count the breath for twenty-one inhalations and exhalations, and meditate for about fifteen minutes. And when it is time to stop, dedicate it as follows: May whatever virtue there has been in my meditation and aspiration become a cause for happiness and comfort for all. Then you can rise and the meditation will be complete.

Related Books

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Eighth Karmapa Mikyo Dorje & Jules B. Levinson & The Eighth Karmapa Mikyo Dorje & Birgit Scott

Introduction to the Middle Way

$32.95 - Paperback

By: Chandrakirti & Jamgon Mipham & Padmakara Translation Group