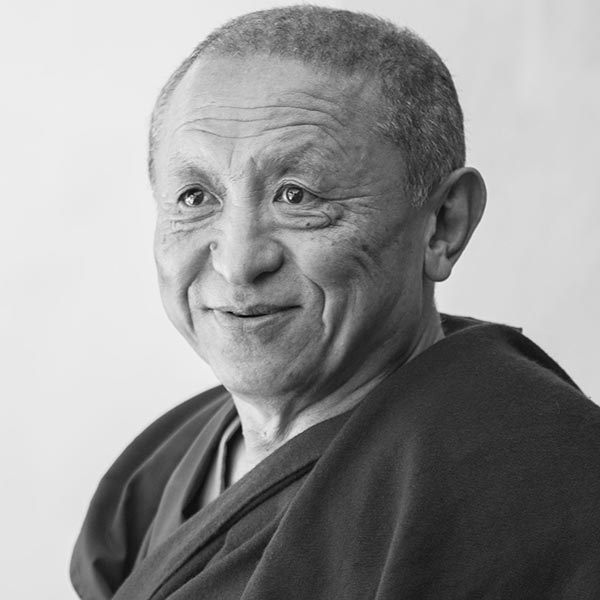

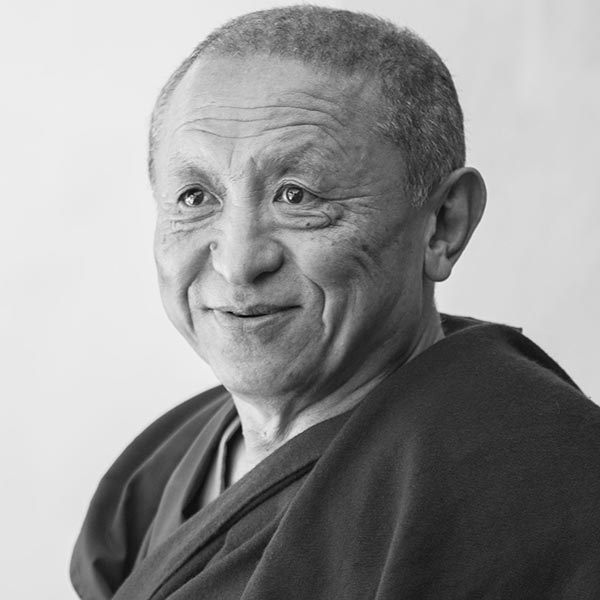

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche

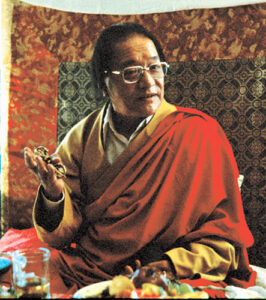

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche is a world-renowned Buddhist teacher and meditation master. He was born in Tibet in 1951 as the oldest son of his mother Kunsang Dechen, a devoted Buddhist practitioner, and his father Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, an accomplished master of Buddhist meditation. As a young child, he was recognized as the seventh incarnation of the Tibetan meditation master Gar Drubchen and installed as the head lama of Drong Monastery in the Nakchukha region, north of the capital city, Lhasa.

In 1959, following the occupation of Tibet, Rinpoche fled with his family to India and Nepal where he spent his youth studying under some of Tibetan Buddhism’s most illustrious masters, including the Sixteenth Karmapa, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, and Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. In 1976 he was enthroned as the abbot of Ka-Nying Shedrub Ling Monastery in Kathmandu, which remains the heart of his ever-growing activity. Today, more than 500 monks and nuns are under his care in this and other monasteries in Nepal. Drong Monastery, which was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, has recently been rebuilt and is again home to a monastic community.

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche is the founder and spiritual head of numerous centers for Buddhist study and meditation in Asia, Europe, and North America. In Nepal, he runs Rangjung Yeshe Institute, an international center of learning where students can obtain BA, MA, and PhD degrees in Buddhist Studies. For those who wish to study and practice from home, Rinpoche also offers an online meditation program, Tara’s Triple Excellence, that covers the entire Buddhist path. At home in Nepal, he is deeply involved in social work through his local charity organization, Shenpen.

To read more about Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche and his activities, visit www.shedrub.org.

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche is a world-renowned Buddhist teacher and meditation master. He was born in Tibet in 1951 as the oldest son of his mother Kunsang Dechen, a devoted Buddhist practitioner, and his father Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, an accomplished master of Buddhist meditation. As a young child, he was recognized as the seventh incarnation of the Tibetan meditation master Gar Drubchen and installed as the head lama of Drong Monastery in the Nakchukha region, north of the capital city, Lhasa.

In 1959, following the occupation of Tibet, Rinpoche fled with his family to India and Nepal where he spent his youth studying under some of Tibetan Buddhism’s most illustrious masters, including the Sixteenth Karmapa, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, and Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. In 1976 he was enthroned as the abbot of Ka-Nying Shedrub Ling Monastery in Kathmandu, which remains the heart of his ever-growing activity. Today, more than 500 monks and nuns are under his care in this and other monasteries in Nepal. Drong Monastery, which was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, has recently been rebuilt and is again home to a monastic community.

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche is the founder and spiritual head of numerous centers for Buddhist study and meditation in Asia, Europe, and North America. In Nepal, he runs Rangjung Yeshe Institute, an international center of learning where students can obtain BA, MA, and PhD degrees in Buddhist Studies. For those who wish to study and practice from home, Rinpoche also offers an online meditation program, Tara’s Triple Excellence, that covers the entire Buddhist path. At home in Nepal, he is deeply involved in social work through his local charity organization, Shenpen.

To read more about Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche and his activities, visit www.shedrub.org.

GUIDES

The Gift of Sadness | An Excerpt from Sadness, Love, Openness

Meditating While Thinking

There is, however, one particular method that benefits everyone alike: acknowledging that nothing lasts. We instinctively feel that things are going to stay more or less the same and that the people around us will remain, but that’s not the case. If we can, we should try our best to understand that things really aren’t the way they seem at all. But if that seems a bit far off at first, it’s still very good to give some thought to the impermanence of things. Even if we just take a quick look around, it’s easy to prove the truth of impermanence. So, first we must acknowledge that things don’t last. Then we need to bring that understanding to mind again and again, until we deeply understand that everything is impermanent and transient. That is a genuine Buddhist meditation.

These days, a lot of people associate meditation with sitting on a cushion, feeling calm and relaxed. So perhaps it sounds a bit strange that reflecting on impermanence can be a meditation. But across all Buddhist traditions, observing the impermanent nature of all phenomena is an important contemplative practice.

The Impact

What happens when we reflect on the impermanent nature of all things? What happens when we really take to heart the fact that everything we are fond of, everything we consider important and meaningful, is going to be lost? What happens when we understand that no matter how well we take care of ourselves, one another, or the whole world for that matter, it’s just a question of time before we will have to say goodbye to it all? When we clearly understand that that’s how life is, when we actually get that, then we will find ourselves overwhelmed by a deep sadness, a sorrow more heartbreaking than anything we have ever known, but this impact is necessary.

The Gift of Sadness

Reflecting on impermanence is not meant to make us miserable. But without that sorrow of knowing nothing will last, we will never get anywhere on our path. Sadness makes it possible for us to gain something that is much more precious than anything we could imagine. That is why we must contemplate impermanence. If there were nothing to gain, it would be foolish to think about these things—we would just be making ourselves miserable for no reason. But there’s a deep meaning to it all. When it dawns on us what the world is actually like, and we are consequently struck by overwhelming sadness, the next step comes naturally. We draw the logical conclusion that all things are impermanent and begin training in letting go.

Sadness makes it possible for us to gain something that is much more precious than anything we could imagine.

Becoming Realistic

Gradually, we are able to let go of all the things we used to chase after blindly, all the things that used to bind us and control us. We develop that ability through a discernment that we normally don’t possess. Instinctively, we begin to let go, because now we know. Whether we like it or not, sooner or later we will be forced to let everything go, so when we know this, it makes perfect sense to lessen our clinging now. Unless we take impermanence into account, we will just continue holding on to things, which in the end will only bring us pain and deprive our lives of meaning. On the other hand, if we have really understood that nothing lasts and that everything is unreal and illusory, then letting go is easy. Actually, it happens by itself without effort. Reflecting on the impermanent and illusory nature of all things is a very powerful practice.

Fresh Eyes

Understanding impermanence is no magical feat, but it dramatically, almost magically, changes our experience of the world. It makes us capable of actions that used to be impossible. We begin to look at our world and ourselves from a completely new perspective, and that profound shift in outlook is actually at the heart of all Dharma practice. In fact, we can measure our spiritual progress by how often we remember that all conditioned phenomena are impermanent. For the most accomplished practitioners, this happens quite spontaneously. They have already then let go.

Waking Up

We begin to awaken, thinking: I’m fooling myself. The way I experience the world and those around me, the way I experience my emotions and myself—it’s all wrong, and it’s painful. All the stuff that I worry about—the things I must have, the things I cannot bear to lose, and the things I try to avoid—it all just keeps me trapped. When I see things in that confused way, it has nothing to do with how they actually are. Moreover, since I am doing this to myself, I am only causing my own suffering. How sad and meaningless!

Breaking Free

We then commit ourselves to breaking free of this outlook: I’m done! From now on, I want to see things for what they really are. I won’t be a slave to my own delusions anymore. I know my perception of the world is completely out of touch with reality. All my daydreams and fantasies, all my worries and fears—they are all trivial and pointless!

As we think in this way, our wish to be free grows stronger. The power of that wish then transforms into a key that unlocks Buddhism’s vast treasury of methods and instructions.

As we think in this way, our wish to be free grows stronger. The power of that wish then transforms into a key that unlocks Buddhism’s vast treasury of methods and instructions.

Opening Up

When we realize that everything is impermanent and unreal, we open up to the pain and suffering of others. That is how love and compassion become heartfelt and genuine. No matter how many praises we sing of love and compassion, such qualities won’t awaken and flourish unless we acknowledge impermanence.

From Sadness to Strength

So many wonderful qualities are already present within us, just waiting to be discovered. The key lies in understanding that things are impermanent and unreal. Sadness, of course, is not an end in itself. But deep sorrow comes with realizing that everything we previously took to be lasting and real is actually just about to disappear—and it never even existed in the first place. Such sadness and disillusionment have a wonderful effect. Sorrow makes us let go. As we stop chasing futile and ultimately painful goals, we embark on the spiritual path with superior strength and resolve.

As we stop chasing futile and ultimately painful goals, we embark on the spiritual path with superior strength and resolve.

The Healing Power of the Dharma

Listening to the Dharma changes us. We begin to feel a profound joy, but we are also struck by tremendous sadness at our confusion and the uncertainty of our situation. So our hearts are heavy, but at the same time we feel that we need not despair, because we have at long last found something that is truly useful and beneficial. The Dharma heals. It is the best medicine, and the more we take that medicine, the more our trust in its wonderful properties will grow. With each passing day, our appreciation of the Buddhist teachings increases as our mind begins to change. That is what it’s like to be directly introduced to the impermanent nature of all things. The realization hits us hard and brings us abruptly out of our sleep. The facts are painful at first, but sadness gives way to a dawning clarity.

Moved by deep joy, we think: Finally, I have a sense of what it’s all about. This change in me is enormous. Now I know how to eradicate confusion and suffering; I know how to be free. I feel so rich, and the road lies open before me. How wonderful!

Maturing

When embarking on the path of Dharma, the mind shifts back and forth between joy and sadness. However, this process gradually matures the mind and makes us flexible, just like a child growing up. But if we really want to leave our spiritual childhood behind, the instructions have to hit home. It’s only when they pierce our heart that things begin to happen.

Related Books

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche is a world-renowned Buddhist teacher and meditation master. He was born in Tibet in 1951 as the oldest son of his mother Kunsang Dechen, a devoted Buddhist practitioner, and his father Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, an accomplished master of Buddhist meditation. As a young child, he was recognized as the seventh incarnation of the Tibetan meditation master Gar Drubchen and installed as the head lama of Drong Monastery in the Nakchukha region, north of the capital city, Lhasa. Read more

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

Personal Reflections: Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche

| The following article is from the Spring, 1997 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Interview With Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche

Short Bio:

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche was born near Lhasa in central Tibet in 1951. When 18 months old, he was recognized by His Holiness the Gyalwang Karmapa as the seventh incarnation of the great yogi Gar Drubchen, an emanation of Nagarjuna. Rinpoche left Tibet before the 1959 communist takeover. In 1974, he moved to Boudhanath, near Kathmandu, and helped his father build the Ka-Nying Shedrup Ling Monastery. Later he was made abbot by H.H. the Karmapa. Fulfilling the wish of his teachers, he has over two decades generously given his time and energy to teaching people from all corners of the world.

The following recent interview with Rinpoche was given to Erik Schmidt for Snow Lion.

Q: We would like to hear some details of your early childhood, and how you were brought up.

Rinpoche: The place I was born is Nakchukha, which lies somewhat near Lhasa. My father, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, came from Kham; my mother near Lhasa.

What follows simply happened, even though it may sound as if I am praising myself. People remarked that my birth was accompanied by various signs; I don't remember all of them right now. However, the sun, the moon, and a star were seen in the sky at the same time; a moment considered to very auspicious. Among the local people my mother's family was quite popular. Her father was the provincial governor, as well as a highly regarded practitioner.

This caused the people to say, Something good has happened. The sun, moon and a star were seen. It must be a rebirth of a great lama.

the sun, the moon, and a star were seen in the sky at the same time; a moment considered to very auspicious.

Other people, said, No, it isn't good. For sure some monastery will come and claim him as the reincarnation of their lama and take the boy away. That will be of no use for us. It is definitely not a good sign.

My grandmother got fed up with the gossiping and said, You don't have to worry about this matter. The child is a girl.

This satisfied the local people and they said, Then it's fine. A girl is OK. At least she will remain around here.

My grandmother's secret lasted for one month. When the word slipped out, people were unhappy. It must be a tulku. For sure he will be taken away. He will not become our future governor.

As a baby it was said that I pointed my finger in the direction of the regional monastery, Bong Gompa, and was heard to say, Bong, bong.

A small group of senior monks arrived on horseback several months later. They went from house to house, making inquiries about newborn children and made a list of their parent's names.

they showed a prediction-letter from the Karmapa

They came to our door. Here they showed a prediction-letter from the Karmapa that stated that the child's father was a vidyadhara, the mother's name was such-and-such, and the birth year sign was such-and-such. The child has moles at the three places of body, speech and mind.

The letter held several other precise specifications. After investigating these details the monks became convinced that I was the tulku of the head lama of Bong Gompa.

My father took me on a visit back to Kham to see his monastery. On pilgrimage to Central Tibet I met with the Karmapa. Earlier my father had named me Chokyi Senge. The Karmapa gave me the long name Karma Samten Yongdti Chokyi Nyima.

When it came time to learn to read my father taught me the alphabet. My father gave teachings every day and I would listen when he explained to people how samsaric pursuits are futile, how nothing lasts, and so forth.

The thought Unless I practice the Dharma, nothing else has any real substance was acutely on my mind.

My mother also taught me. She used to read aloud from Milarepa's life story and songs. Hearing these stories repeatedly I developed a strong faith in this great master. It inspired in me a deep-felt renunciation for samsara. The thought Unless I practice the Dharma, nothing else has any real substance was acutely on my mind. While she read we both often wept.

My mother also read from the biographies of Tilopa, Naropa and Marpa. Especially inspiring was the life of Buddha Shakyamuni and the stories from his former lives, the Jataka and the Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish.

She would read in a very clear voice, not just reading from a history book of dry facts, but in a way that was most moving. She could really touch a child's heart with these profound stories.

I felt the pointlessness of clinging to samsaric things such as the fleeting pleasures of this life.

Avalokiteshvara, Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion

Since I don't have any special qualities, it must be due to my parents that from early childhood there was a natural sense of compassion. I never felt to harm anyone, and towards anyone who needed help I would give it. At this time I felt the pointlessness of clinging to samsaric things such as the fleeting pleasures of this life. To attain liberation and enlightenment, I thought, is probably not that easy, but though very young I did form the wish to be able to embark on that path. Those were some of my good sides. I had many nasty sides as well, all the various disturbing emotions.

After arriving in India I was sent to Young Lamas Home School, probably at the age of eleven, and stayed there for a little less than a year. Here were assembled many learned teachers from all four schools: Geluk, Sakya, Kagyii, and Nyingma. We were 52 young refugee tulkus. At some point a messenger came and said that the Karmapa ordered me to go to Rumtek. It happened all of a sudden; even my parents didn't know. They had sent someone to fetch me for the holidays, but the escort found that I had already left.

At Rumtek, the Karmapa's monastery in Sikkim, I stayed for many years. This was a time for studying the main Buddhist scriptures and some of the traditional sciences. Especially we had the fortune to receive many transmissions of empowerments and teachings. During these years many other important masters visited Rumtek like Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse and Khamtriil Rinpoche. Not only from them but from many other great masters I was able to receive teachings. These masters include Kunu Lama Tendzin Gyaltsen, Khenpo Rinchen, and Khenpo Dazer.

As our understanding and experience deepen, it is a natural consequence that our trust in and appreciation of true spiritual qualities in others deepen as well, with no prejudice to who they are.

Since then I have met many masters from all traditions, including His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the lord of the Dharma in the Land of Snow, Gyalwang Karmapa, Sakya Gongma Rinpoche, and Minling Trichen Rinpoche. From such grand masters, I have had the fortune to receive many empowerments, reading transmissions and instructions. Besides them I have pursued with great interest instructions from a variety of teachers from all schools, with or without lofty position, who were monks or ngakpas. These instructions have greatly benefited my mind and I consider myself very fortunate.

To practice these teachings is my responsibility; if I don't, it is my mistake. Nevertheless, I have the confidence that I indeed have received a wealth of instruction. To be satisfied with only that type of confidence can be a grave error. My mother told me this when she was at the verge of death,

There is no point in being proud because you are a tulku. There is also no point in being proud because you have studied the books and received a lot of empowerments and transmissions. You need to soften your heart, make your stream of being gentle, practice a lot. Without practicing, it is not enough to be conceited and think I'm a tulku! There is nothing flabbergasting about having read through stacks of scriptures. The main point is to scrutinize your attitude and practice to improve yourself. The Buddhist practice should be taken personally to heart.

Make yourself more gentle, soft, peaceful, loving, compassionate, and insightful concerning the empty nature of things. Always check yourself to see whether you improve in these areas. Check yourself, but also question an authentic master, make an offering of your understanding. Behave in a straightforward way, don't pretend to be special, otherwise your life becomes a great delusion. You won't find many people who dare to tell you this. Most people will simply offer praise, telling how nice you are. I am honestly telling you this.

On the one hand, what she said was very kind, but on the other hand it was like a scolding.

Since what she said was a teaching in itself, I therefore consider my mother as one of my teachers. I do so now, but not before she passed away.

In Tibetan Buddhism, a white khata symbolizes the pure heart of the giver.

When she was about to die, my mother first gave a white scarf, then said this. It went straight into my heart and was extremely helpful. She was tearful, she was about to die, she knew that she was dying, we also knew she was on the verge of passing away. She had no anxiety about that. She continued by saying,

The best practitioner is someone who dies gladly. I am not exactly glad, but I am definitely not depressed. I have no regrets and no fear. This is due to having received many pithy instructions and practiced a little. I have trained in order for it to be useful for leaving this life.

Since what she said was a teaching in itself, I therefore consider my mother as one of my teachers. I do so now, but not before she passed away.

Q: Please tell some stories about the more unusual of your teachers.

Rinpoche: Among the more unusual of my teachers, there is Khenpo Rinchen. Once he said to me,

You are really fond of studying the scriptures. We get along quite well. It would therefore be good if I share with you some explanations of the difficult points of Buddhist philosophy.

He would make sure the door was locked and then dive into the intricate world of scholars. After a while of speaking, he would close the books, take off his glasses, shut his eyes, and talk for hours. He could speak hours upon end and yet not exhaust the topics.

Khenpo Rinchen did many unusual things, like walking around without shoes, or without his monk shawl, having forgotten to put them on. One time he went to relieve himself on a field near where Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse's monastery now stands. While squatting, he began to read a book, and continued to read even after. His deep interest absorbed him to such an extent that he totally forgot time and place. After a while he sat down right on top of it. When he returned, people had to hold their noses.

This Khenpo had no interest in ordinary things like food and clothes. His whole attention was absorbed in the books. He often became oblivious to the rest of the world. As he regarded all other affairs as unimportant and paid no attention to them, they were forgotten. He was one unusual teacher.

he was always practicing, always in samadhi, peaceful and wide awake.

Another unusual among my teachers, though in another way, was Kunu Lama Tendzin Gyaltsen (1894-1977). Whenever you saw him, he was always practicing, always in samadhi, peaceful and wide awake. He didn't seem to require any shrine objects. No matter which philosophical treatise he was expounding, no matter what difficult point, he would always connect them with the practice [of the awakened state]. No training, no use! he would say. When you compare and align the statements in the words of the Indian panditas and the writing of the learned masters of Tibet, you can surely find discrepancies in intent and meaning, but Kunu Lama was able to establish how all the levels of philosophy are without conflict, without any real contradiction. That truly helped my understanding.

Khenpo Rinchen, on the other hand, would line everything up as being in conflict, nothing was totally the same. Then he would explain how and why, and break into laughter. That approach actually also helps in developing the power of insight.

Rinpoche's manner of speaking was markedly beautiful, his words were eloquent, like reading from a commentary without a single mistake.

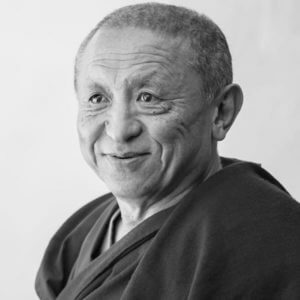

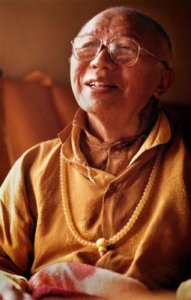

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910–1991)

At the feet of Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse, I received so many transmissions. Rinpoche's manner of speaking was markedly beautiful, his words were eloquent, like reading from a commentary without a single mistake. His speech came like a unbroken flow, even while taking a sip of tea. You had the feeling that he was inexhaustible, and yet the unending words were all meaningful and new. Something learned by heart you can of course recite like that, but it will always sound the same. This quality, on the other hand, is known as longdol, 'overflowing from within'. This overflow of wisdom from within happens when someone reaches a high level of practice.

Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse's brother, Sangye Nyenpa Rinpoche, lived at Benchen Gompa in eastern Tibet. As the grand lama of a huge monastery he was free to invite many khenpos to give teachings, and he became well studied. Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse at that time had no monastery and didn't have the name of a tulku. He wandered from place to place, receiving teachings from various lamas, sometimes staying in retreat in the mountains.

The knowledge through meditation is unlike what you can learn and figure out, which is always limited. Wisdom that overflows from within is inexhaustible.

Once, when he came to Benchen after a retreat, Tenga Rinpoche asked Sangye Nyenpa,

Of you two brothers, who is the most learned?

Sangye Nyenpa Rinpoche replied,

In the past it was I. Due to my status and monastery, I was able to invite so many good teachers. Now, after all his years of retreat, I am no match for him any longer. His knowledge has totally overflowed from within. His type of knowledge is the one that results from meditation training. Mine is mainly from study and reflection.

After that Sangye Nyenpa always showed immense respect for Dilgo Khyentse.

The knowledge through meditation is unlike what you can learn and figure out, which is always limited. Wisdom that overflows from within is inexhaustible. Another point is, it is totally free from mistakes, in both words and meaning. Otherwise, even an extremely learned person sometimes does make an error, for instance getting the sequence wrong, or forgetting to say a few words in a sentence. When knowledge truly overflows from within there is no error in words or meaning. It is all right to call that 'mind-treasure'. Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse was truly amazing.

When knowledge truly overflows from within there is no error in words or meaning. It is all right to call that 'mind-treasure'.

Dudjom Rinpoche, Kyabje Dudjom Rinpoche or Dudjom Jikdral Yeshe Dorje (1904–1987)

From Kyabje Dudjom Rinpoche I received the Tersar empowerments, and my father brought me along many times for mind-teachings, instructions on the nature of mind. At the end of each instruction I felt, Today I really understand! After a few months, I walked away with the feeling, Today was totally different, even clearer than before. Every time you met him there was some new depth of benefit. I don't know what is was; probably his great blessings.

In short, I had the chance to assimilate knowledge from many sources, without prejudice to lineages, and these masters helped my understanding improve. On the other hand, since it fell upon me to help found a monastery, create the resources for a sangha of monks, and meet with many people, I haven't found the time to single-heartedly pursue the knowledge from learning, reflection and meditation. All this work is of course supposed to be for the sake of the Dharma, but how much it benefits will have to be seen.

My aim is wholeheartedly to assist in spreading the Buddha's teachings. In this my intention is pure. When receiving people I want to help them. I always try my best to teach them in the most beneficial way. However, it may be difficult to benefit others deeply since I don't have the necessary qualities of wisdom, compassion, and abilities.

This was my life story in brief.

My aim is wholeheartedly to assist in spreading the Buddha's teachings. In this my intention is pure.

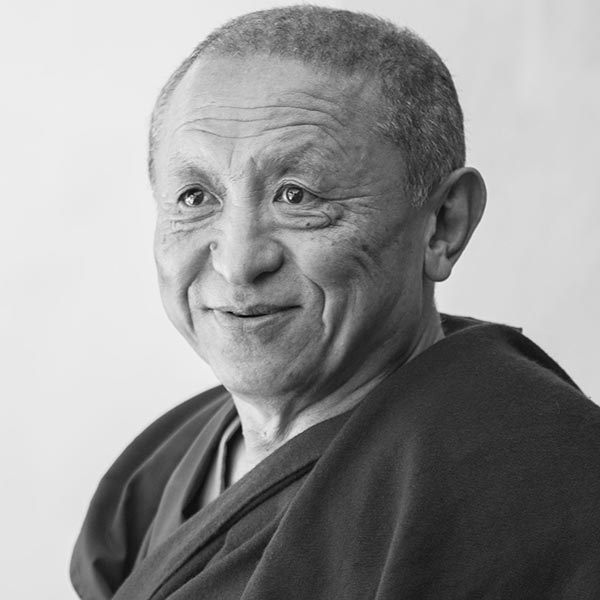

Q: Please comment on your relationship to your father.

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche (Tib. སྤྲུལ་སྐུ་ཨོ་རྒྱན་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་, Wyl. sprul sku o rgyan rin po che) (1920–1996)

Rinpoche: Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche was my father so in that respect he was 'daddy', but at the same time he was also my guru. When someone is both your father and your guru the relationship becomes quite unusual.

As one's father, there is of course the family closeness and affection. When connected to someone through the master-disciple link, there is a deeper trust. The main reason for this trust consists in having received many pithy instructions which you have tried out and proved useful in a very real way. Such trust is something natural; it can be called faith through knowing the reasons.' There is not much point in trusting someone unconditionally merely because he is your father. This trust is also not only because he has given me empowerments and teachings.

There is a certain type of trust that grows stronger as you understand more, as you progress in your personal experience, as the inner tightness loosens from deep within. I'm not simply talking about my father here, but one's relationship to the great masters of all the lineages. As our understanding and experience deepen, it is a natural consequence that our trust in and appreciation of true spiritual qualities in others deepen as well, with no prejudice to who they are. Before that we may be inclined to have faith only in our particular lineage masters, or only those from whom we personally received some transmission in the form of empowerment or instruction.

As our understanding and experience deepen, it is a natural consequence that our trust in and appreciation of true spiritual qualities in others deepen as well, with no prejudice to who they are.

Isn't this because the real substance of the Buddha's teachings consists of knowledge and compassion?

Knowledge here refers to emptiness, or what the general teachings call the knowledge that realizes egolessness, or what the tantric teachings call intrinsic awareness or self-existing wakefulness. In the Dzogchen instructions, it is called the primordially pure awakened state, in Mahamudra it is mental 'nondoing'. In our studies it is the true meaning of this we are supposed to reflect upon repeatedly to discover and apply in our training and to gain personal experience of.

As our understanding and experience begin to unfold, even to a small degree, isn't it true that we begin to appreciate genuine spiritual qualities in all masters, no matter to what school they belong? Isn't it true that we can't help it; that it arises naturally?

The consequence is that narrow-minded prejudice and sectarianism begin to shrink. We begin to acknowledge that all the different philosophical schools and lineages have their place and individual, unique qualities. It is said that we should become able to see all scriptures as personal instruction and establish that all teachings are without conflict. This is true.

As our understanding and experience begin to unfold... we begin to appreciate genuine spiritual qualities in all masters, no matter to what school they belong.

Q: What changed in your life by your father's passing?

Rinpoche: It wasn't only my father who died; it was the passing of my root guru as well. It gave a very strange and difficult feeling. When both die it is as if two people very close to you pass away at the same time. Unless you can raise your view and think on a larger scale, it is a very hard time.

Luckily, thanks to the Buddhadharma, we know that all things must pass. Since I have heard many true teachings and paid heed to them, this troublesome point in my life didn't turn overwhelming or unbearable. We have to face the facts now. Take care!

In short, it has sharpened my vow to help others in learning and practice.

The teachings of Buddha Shakyamuni should flourish all over the world and there are many predictions that this will happen.

Q: How did it come about that you have links to so many foreigners?

Rinpoche: The teachings of Buddha Shakyamuni should flourish all over the world and there are many predictions that this will happen. I feel it has to happen because the Buddhadharma is simply the nature of things. It helps your heart and attitude. Whoever practices sincerely is in harmony with others, has less conflict, and finds him or herself in better circumstances.

Why? Because the main principles in Buddhism are knowledge and compassion. It is the deepening of compassion that brings welfare and happiness to all. It is the deepening of knowledge that eradicates ignorance, misunderstanding, doubt and imperfect understanding, after which sublime wisdom overflows from within. Don't you also feel that the time is right for the Buddha's teachings?

The main point is to be compassionate and gain certainty in the view of emptiness and dependent origination. I have the conviction that once you gain such certainty, the other secondary points come easily.

Another reason is that I always had, even as a small child, the impetus to help people understand whatever it is they haven't understood. On top of that, the Gyalwang Karmapa, Dudjom Rinpoche, Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse, and also my precious father told me to uphold the Buddhadharma. Even though from time to time I asked if it wouldn't be better to stay in retreat, they said,

Uphold the teachings, uphold the teachings.

Once I asked the Karmapa to do the three-year retreat at Rumtek; he didn't give permission. Later I asked my father many times if I could build a small meditation cabin at Nagi Gompa and remain in retreat for a couple of months every year. His response was,

Of course it's good, but there are not so many to uphold the Buddhadharma.

Knowledge and compassion are the basis to which the word Buddhism refers. Whoever trains in knowledge and compassion will be in harmony with others both right now and ultimately. This is an indisputable truth

Therefore I try to practice while at the same time helping the Dharma and others. Maybe it's not right for me this time around to stay in strict retreat. Maybe I don't have the karma. I don't know.

When I was about fourteen, while staying at Rumtek, I knew some foreigners. The number increased after coming here to Nepal. They have told me that they find what I say helpful, suitable.

From my side, it is my impression that Westerners are inclined to immediately understand teachings on emptiness and compassion. There is a certain lack of readiness to accept the law of karma and rebirth. I don't feel that this is an insurmountable problem; it will be solved as we go along. I feel that faith, karma and rebirth are not the main issue in Buddhism.

The main point is to be compassionate and gain certainty in the view of emptiness and dependent origination. I have the conviction that once you gain such certainty, the other secondary points come easily.

Don't you also feel that the time is right for the Buddha's teachings?

Q: Please explain your main activities here.

Rinpoche: We built the monastery Ka-Nying Shedrub Ling to house the representations of enlightened body, speech and mind, in Boudhanath, Nepal. We built monk's quarters and let monks reside there to pursue the knowledge resulting from learning, reflection and meditation, and to train in the skills of teaching, debate, and composition in order to help others.

Without the proper basis in studies and reflection it is difficult to immediately have success in meditation practice. That is why we have a Shedra section, a monastic college where the monks study the main scriptures. Those who have gained a sufficient understanding are allowed to do the three-year retreat. After having completed the traditional retreat, there are some of the retreatants, though not every one of them, who have reached a quite good level of practice, and so are able to function as a lama. These are the people I send out to assist others wherever there is a need. They are capable to give instructions and spread the Dharma.

These days I see a growing interest among foreigners in the Buddha's teachings.

Additionally, my father expanded the nunnery at Nagi Gompa to include more than one hundred nuns. With his passing I have taken over the responsibility for Nagi Gompa. Some of the nuns do sadhana practice in retreat, while the majority study the scriptures with the resident khenpo. At present we have five nuns in the three-year retreat soon followed by an additional ten. I also offer guidance and support for the Asura Temple and retreat center, and a few additional temples here and there, including a small monastery on the border with India. I am embarking upon a project for a large temple in Lumbini, the birth place of Lord Buddha.

Erik, my translator, under my direction has translated more than 20 books. It is my wish that these will travel and be of help to people in many different countries. In the future as well, I hope that this effort will continue by educating foreigners here, to translate a great number of Buddhist texts for the welfare of people everywhere.

In connection with this, when I visited some countries abroad, I was repeatedly faced with this question, sometimes in a rather pushing way:

Where can we study the Dharma more seriously? Why are you not arranging something? If you don't, who will?

In India, there are study places for foreigners in Varanasi and Dharamsala, but in Nepal there is no solid school establishment besides a few sporadic sets of teaching. I have therefore since a quite a few years formed the wish that we should make a Shedra for foreigners in Boudhanath. The Rangjung Yeshe Shedra began autumn, 1997. The main participants will be the khenpos, below them the translators, and then all the students, whatever their number.

Boudhanath is the largest stupa in Nepal and one of the largest stupas in the world.

Q: You also teach university programs from the West, from Antioch and so forth, in India and here at the yearly seminar. Could you mention those?

Rinpoche: I visited the Antioch program in Bodhgaya for the first time in 1984. Every year since then I have taught there. I have always found the students to be young and fresh, quite intelligent and open-minded. It has been a delight to teach them the Dharma.

Many students end up taking the refuge precepts out of sincere trust. Some are quite serious and I see them again after a couple of years, some after ten years. Many come and tell me they are studying the Buddha's teachings, practicing meditation.

The seminar in Boudha has gone on since 1981. For 15 of these years since then, we were fortunate enough to receive teachings and do practice with my father. 1997 was the first time without him and we have added the opportunity to do more intensive practice at his hermitage. Two of my brothers, Chokling Rinpoche and Tsok Nyi Rinpoche also taught during that year and will continue into the future.

My activities are taking root in the West. International Meditation Centers can be found listed at the bottom of this link's page.

The Dharmachakra at the Driraphuk Gompa Buddhist Monastery and Mount Kailash in Western Tibet.

Q: As a conclusion, what is the essence of Buddhism?

Rinpoche: Knowledge and compassion are the basis to which the word Buddhism refers.

Whoever trains in knowledge and compassion will be in harmony with others both right now and ultimately. This is an indisputable truth.

All of us should try our best to study about knowledge and compassion, next to reflect upon them, but especially to gain direct insight within ourselves. That brings immense benefit.

Tashi delek to all of you.

Books by Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche:

Union of Mahamudra and Dzogchen

Books by Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche:

Repeating the Words of the Buddha Advice from the Lotus-Born

$29.95 - Paperback

By: Andreas Doctor & Cortland Dahl & Dharmachakra Translation Committee & Getse Mahapandita Tsewang Chokdrub & Jigme Lingpa & Patrul Rinpoche