Grace Schireson

Grace Schireson is a teacher in the Suzuki Roshi lineage, Soto Zen tradition, empowered by Sojun Mel Weitsman. She has also practiced in the Rinzai tradition and was encouraged to teach koans by Keido Fukushima Roshi. Grace is the author of Zen Women and co-editor of Zen Bridge. Grace is the head teacher of the Central Valley Zen Foundation, president of the Shogaku Zen Institute, and teaches meditation at Stanford University. She is also a clinical psychologist.

Grace Schireson

GUIDES

Zen in Japan: Up to the Meiji Restoration

This is part of a series of articles on the arc of Zen thought, practice, and history, as presented in The Circle of the Way: A Concise History of Zen from the Buddha to the Modern World. You can start at the beginning of this series or simply explore from here.

Explore Zen Buddhism: A Reader's Guide to the Great Works

Overview

Chan in China

- The Works of the Chan and Zen Patriarchs

- The Works of Zen in the Tang Dynasty (618-907)

- The Works of Zen in the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279)

- The Great Koan Collections

Zen in Korea

Zen in Japan

- Early Zen in Japan

- Dogen: A Guide to His Works

- Rinzai Zen

- Hakuin Ekaku: A Reader's Guide

- The Samurai and Zen

> Zen in Japan up to the Meiji Restoration

Additional Resources

- The Heart Sutra: A Reader’s Guide

- Zen in the Modern World (Coming Soon)

- Foundational Sutras and Texts of Zen (Coming Soon)

- Zen and Tea

The period after Dogen and the early period of Zen saw rich developments, including of course the Rinzai school and the Samurai which are covered in the sister guides to this article. Here are some of the works we publish from after the early period up to the 19th century Meiji Restoration when changes in power made for a more challenging environment for Zen practitioners and institutions throughout Japan.

Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record: Zen Comments by Hakuin and Tenkei

Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record is a fresh translation featuring newly translated commentary from Hakuin of the Rinzai sect of Zen and Tenkei Denson (1648–1735) of the Soto sect of Zen.

Ryokan

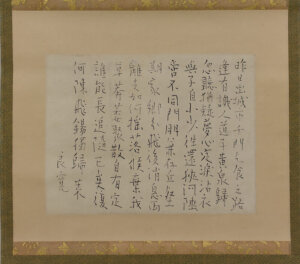

Chinese Poem Lamenting the Death of a Friend by Ryokan from the Met

Ryokan (1758–1831) is, along with Dogen and Hakuin, one of the three giants of Zen in Japan. But unlike his two renowned colleagues, Ryokan was a societal dropout, living mostly as a hermit and a beggar. He was never head of a monastery or temple. He liked playing with children. He had no dharma heir. Even so, people recognized the depth of his realization, and he was sought out by people of all walks of life for the teaching to be experienced in just being around him. His poetry and art were wildly popular even in his lifetime. He is now regarded as one of the greatest poets of the Edo Period, along with Basho, Buson, and Issa.

Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan

He was also a master artist-calligrapher with a very distinctive style, due mostly to his unique and irrepressible spirit, but also because he was so poor he didn’t usually have materials: his distinctive thin line was due to the fact that he often used twigs rather than the brushes he couldn’t afford. He was said to practice his brushwork with his fingers in the air when he didn’t have any paper. There are hilarious stories about how people tried to trick him into doing art for them, and about how he frustrated their attempts. As an old man, he fell in love with a young Zen nun who also became his student. His affection for her colors the mature poems of his late period. This collection contains more than 140 of Ryokan’s poems, with selections of his art, and of the very funny anecdotes about him.

Dewdrops on a Lotus Leaf: Zen Poems of Ryokan

Deceptively simple, Ryokan's poems transcend artifice, presenting spontaneous expressions of pure Zen spirit. Like his contemporary Thoreau, Ryokan celebrates nature and the natural life, but his poems touch the whole range of human experience: joy and sadness, pleasure and pain, enlightenment and illusion, love and loneliness. This collection of translations reflects the full spectrum of Ryokan's spiritual and poetic vision, including Japanese haiku, longer folk songs, and Chinese-style verse. Fifteen ink paintings by Koshi no Sengai (1895–1958) complement these translations and beautifully depict the spirit of this famous poet.

One Robe, One Bowl: The Zen Poetry of Ryokan

The hermit-monk Ryokan, long beloved in Japan both for his poetry and for his character, belongs in the tradition of the great Zen eccentrics of China and Japan. His reclusive life and celebration of nature and the natural life also bring to mind his younger American contemporary, Thoreau. Ryokan's poetry is that of the mature Zen master, its deceptive simplicity revealing an art that surpasses artifice.

Ikkyu

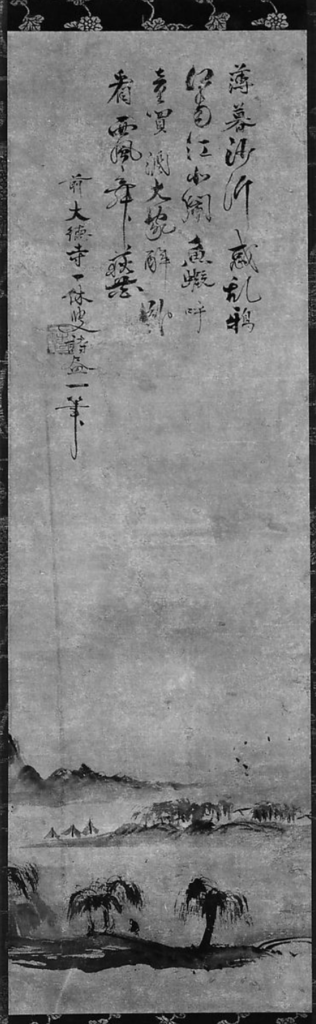

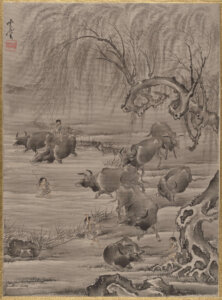

Twilight Landscape

In the Style of Ikkyū Sōjun Japanese. From the Met.

Finally, there is the figure of Ikkyu (1394–1481). While we do not have any stand-alone works on or by him, he appears in many, many works. In The Circle of the Way, he gets a few pages that begins:

Of all Muromachi-period Zen monastics, with all of their talent and accomplishments, the monk most well known today was something of a black sheep. Ikkyu Sojun (1394–1481) remains so popular in Japan that he has been portrayed in anime and the popular graphic art of manga.

Peter Matthiessen, In Nine-Headed Dragon River: Zen Journals, adds more color with his flowing prose, describing him as

A bastard son of the emperor, pauper, poet, twice-failed suicide, and Zen master, enlightened at last by the harsh call of a crow. At eighty-one Ikkyu became the iconoclastic abbot of Daitoku-ji. ('For fifty years I was a man wearing straw raincoat and umbrella-hat; I feel grief and shame now at this purple robe.') His 'mad' behavior was perhaps his way of disrupting the corrupt and feeble Zen he saw around him: 'An insane man of mad temper raises a mad air,' he wrote. He also said, 'Having no destination, I am never lost.' One infatuated scholar has called him 'the most remarkable monk in the history of Japanese Buddhism, the only Japanese comparable to the great Chinese Zen masters, for example, Joshu, Rinzai, and Unmon.' Ikkyu found no one he could approve as his Dharma successor. Before his death, civil disorders caused the near obliteration of Kyoto, forcing Rinzai Zen to follow Soto from the decadent capital city into the countryside.

by Jim Harrison

A collection of poems inspired by Ikkyu by the great novelist and essayist Jim Harrison who said of this work,

The sequence After Ikkyu- was occasioned when Jack Turner passed along to me The Record of Tungshan and the new Master Yunmen, edited by Urs App. It was a dark period, and I spent a great deal of time with the books. They rattled me loose from the oppressive, poleaxed state of distraction we count as worldly success. But then we are not fueled by piths and gists but by practice—which is Yunmen’s unshakable point, among a thousand other harrowing ones. I was born a baby, what are these hundred suits of clothes I’m wearing?

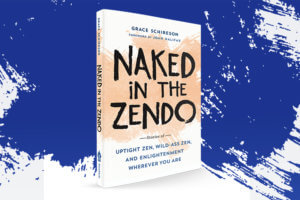

Naked in the Zendo: Stories of Uptight Zen, Wild-Ass Zen, and Enlightenment Wherever You Are

While not by Ikkyu, he makes an appearance in this work over a few very entertaining and moving pages.

Zen in the Age of Anxiety: Wisdom for Navigating Our Modern Lives

Ikkyu makes an appearance for several pages of Tim Burkett's excellent work which includes translations, by John Stevens, of several of his poems

You Have to Say Something: Manifesting Zen Insight

Dainin Katagiri Roshi shares this story about Ikkyu in this work:

A man who was soon going to die wanted to see Zen master Ikkyu. He asked Ikkyu, ‘‘Am I going to die?’’ Instead of giving the usual words of comfort, Ikkyu said, ‘‘Your end is near. I am going to die, too. Others are going to die.’’ Ikkyu was saying that we can all share this suffering. Persons who are about to

die can share their suffering with us, and we can share our suffering with those who are about to die.Ikkyu’s statement comes from a deep understanding of human suffering. In facing your last moment, you can really share your life and your death.

Minding Mind: A Course in Basic Meditation

One of the meditation manuals in this work date from pre-Meiji Restoration Japan.

The second, An Elementary Talk on Zen, is attributed to Man-an, an old adept of a Soto school of Zen who is believed to have lived in the early seventeenth century. The Soto schools of Zen in that time traced their spiritual lineages back to Dogen and Ejo , but their doctrines and methods were not quite the same as the ancient masters’, reflecting later accretions from other schools.

Man-an’s work is very accessible and extremely interesting for the range of its content. In particular, it reflects a modern trend toward emphasis on meditation in action, which can be seen in China particularly from the eleventh century, in Korea from the twelfth century, and in Japan from the fourteenth century.

Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice

This recent work by Professor Charles B. Jones, a leading scholar on Pure Land Buddhism, goes into much detail of Pure Land and its intertined relationship with Zen. The sections on Japan include its introduction from China, Ryonin and the Yuzi Nenbutsu, Honen and Jodo Shu, Shinran and the Jodo Shinshu, and Ippen and the Jishu.

Continue to our next article in the series: A Readers Guide to the Heart Sutra >

The History of the Zen Nuns’ Practice

Excerpt from Naked in the Zendo

Early in my Japanese monastic practice, I had a wonderful trip to Eiheiji, the head temple for Soto Zen in Japan. Eiheiji has the stature and grandeur of the Vatican in Rome. Its scenery, dignity, deep practice, and beautiful furnishings inspire reverie and command presence. I was visiting Eiheiji for the shuso ceremony for Shungo Suzuki. Shungo, the son of Hoitsu Suzuki Roshi and the grandson of Suzuki Roshi, had earned the top honorary position among the monks that year resulting in his shuso ceremony. Several busloads of Rinso-in danka-san, members of Suzuki’s home temple, were traveling to Eiheiji for the ceremony. It was a full day’s ride, which included karaoke on the bus. I distinguished myself in karaoke with my rendition of the Beatles’ “Yesterday,” receiving several compliments on my excellent English.

The shuso ceremony took place over the course of several days. I shared a room with Hoitsu Suzuki Roshi’s wife and daughters. As they prepared for their formal appearance in kimono and traditionally styled long hair, I was astonished at their ability to breathe with hairspray so thick. Although I had to admire the architectural handiwork of their elaborate hair, as their roommate I became concerned that I would experience death by hairspray.

It became clear to me that I faced a bigger danger in the hours ahead. I might die—or at least be permanently paralyzed—by seiza posture—kneeling with hips on ankles, without a cushion, on a tatami mat.

Another Eiheiji hazard concerned my fear of death by intestinal blockage. Every meal was rice, pickles, and unidentifiable fried rubbery stuff (most likely fried tofu). In texture, it closely resembled vulcanized rubber tire. I’m sure the meals were lavish by monastic standards, and delicious to Japanese people who seem to have evolved a genetic ability to digest vulcanized rubber tofu. I was not nearly as talented; in fact, I am intestinally challenged. I managed to survive the food challenge because of my American seatmate at the table. He was exceptionally sturdy, and he loved Japanese food. I would surreptitiously pass most of my food to him, and I could eat my dried fruit and nuts later in secret. Finally, even he had eaten enough, and he refused my offerings. At that point I had to sneak the leftovers out in my sleeve. Mottainai—one must never waste!—was a common expression in Zen temples.

While I was fairly certain I had avoided the first two death threats—death by intestinal blockage and death by massive hairspray inhalation—it became clear to me that I faced a bigger danger in the hours ahead. I might die—or at least be permanently paralyzed—by seiza posture—kneeling with hips on ankles, without a cushion, on a tatami mat. The ceremony included many uninterrupted hours of seiza. I was fifty-two years old at the time, and I had already used up most of my knee cartilage through many years of zazen seated in the lotus posture. The beauty of Eiheiji, the rituals, the early mornings, and the fears of perishing all served to amplify my awareness.

At the shuso ceremony, I was seated among the gonin, the honorable guests of the Suzukis. I learned a great deal from these honorable older priests. First, they had done their rigorous training as young men. Sitting meditation all day and all night was no longer required of them. And they would sneak in their zagus, their bowing cloths, in order to cushion their knees. I marveled that we had not learned in America how to protect ourselves from permanent knee damage as we aged. I guessed we missed out on “old priest” practice because the founding teacher at San Francisco Zen Center, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, had died when we were still young. His young disciples hadn’t learned how older priests coped, how to cope with aging when facing Zen’s physical challenges.

Older temple priests and one temple nun, Shunko-san, were among the gonin. The nun had excellent old-age technique; she concealed a fold-up seiza bench in her very large formal robe sleeves and brought it out to use for the ceremony. A seiza bench has two wooden ends and a padded seat. The bench elevates the buttocks off the cushion, relieving pressure on knees and thighs. I could only marvel at her genius. She had anticipated the full-length horror of the seiza, and she had prepared by sneaking the small but effective seiza bench into the zendo inside her sleeve.

Soon her scheme was interrupted by an Eiheiji temple monk official who told her that he “was sure she would be more comfortable in a chair.” Without the faintest hint of reluctance, and offering a formal bow of gratitude, she accepted the chair as her seat and put the bench back in her sleeve. Of course, she had known all along that the chair was an option but had chosen a more dignified seated position on the bench. I understood the embarrassment that she faced being seen seated in a chair, differently from all the other male monks. I felt her discomfort keenly since we were the only two ordained women among the hundreds of male priests. As far as we could tell, all the men were sitting in seiza, presumably ready to face their own crippling demise.

Admonition of monks by nuns is forbidden; admonition of nuns by monks is not forbidden.

The entire history of the Zen nuns’ practice weighed on me in that moment, when past, present, and future became fused. How will I express the history in this moment that nourishes the future? Specifically, I was reminded of the Buddha’s refusal to allow women ordination. The nuns, whose ordination restrictions put them in a second-class order, endured humiliations and attacks throughout the centuries. And now this confrontation right before my eyes at the head temple for the Soto Zen sect. As I thought about my female Zen ancestors, I recalled the Eight Special Rules for Buddhist nuns. In particular, number 8, as worded in my book Zen Women, sums them up:

8. Admonition of monks by nuns is forbidden; admonition of nuns by monks is not forbidden.

Based on early Buddhist rules, nuns were under the direction of monks. The most senior nun was junior to the most junior monk. Looking at my fellow female Zen nun Shunko-san, it was clear that she was senior to this Eiheiji monk. I knew she had her own temple. The same was true of me. But our functional seniority was irrelevant in this formal Japanese setting. Sometimes the weight of twenty-five hundred years lands on one moment, intensifying attention and awareness. I couldn’t argue with this junior monk on Shunko-san’s behalf—according to the Buddha’s teaching, he was her senior.

Again I reached deeply into my awareness and my responsibility to the nuns’ order. How was I to make a statement and still be part of the ceremony without disgracing the Suzuki family? I waited until the young monk official departed and quietly asked Shunko-san if I could borrow the bench. She passed it over. As soon as I had made myself comfortable on the seiza bench, the young monk returned. He repeated his assurance that I would be much more comfortable in a chair. I did not want to sit in a chair, fearing that in the future Abbess Zenkei Blanche Hartman would see pictures of the ceremony and scold my feeble representation of Western Zen women at Eiheiji. Zenkei Blanche Hartman had been the first female abbess at San Francisco Zen Center; she was a mentor and close friend. She had inspired me, and I wanted to inspire other women to forge ahead despite the hardships. I did not want to seem less able than the monks while representing all of my female ancestors.

Unlike Shunko-san, the Japanese Soto nun, I did not report to Eiheiji temple as an American Zen nun. In fact, American Soto Zen nuns don’t follow the Eight Special Rules. How could I hold my ground and stand up for the women’s lineage? I looked the monk squarely in the eyes and said “Arrigato, demo iie” (Thank you, but no) with a genuine smile. The monk’s expression changed from being in command to rapid deflation. He had probably never encountered insubordination by a woman in his formal role. He left our seating area immediately. He may have instinctively believed in the Eight Special Rules and relied on the authority of his position, but in this particular exchange he didn’t have a way to enforce those rules.

I was able to sit upright, in endurable pain, on my seiza bench for the several-hours-long ceremony. I couldn’t tell if I was uplifting or disgracing the women’s lineage, so I sat taller. Some others seated around me experienced near-death by seiza. My rather accomplished and sturdy American male seatmate was even reduced to groaning. I had often wondered whether strong ligaments, tendons, and joints were seen as equivalent to Zen accomplishment. Do we glorify teachers who can sit seiza and full lotus—mistaking good joints and balanced musculature for spiritual accomplishment?

After the ceremony, the Suzuki family marveled at my miraculous seiza stamina and my continuing ability to walk. The family had been seated at a distance in the ceremonial hall that seated several hundred observers. I confessed my use of the bench to the Suzuki family, and we laughed together. From a distance, my use of the bench was hidden under my robes, enabling me to look stronger than I was. From a distance, maybe you couldn’t tell whether I was a monk or a nun. Perhaps exposing my inability, and allowing the monks’ seiza fortitude to shine in contrast, was the intended purpose of putting me and Shunko-san in chairs. Maybe, like all of women’s history in Buddhism, we were being put in our place. But I have never been good at getting into that position.

Feeling the weight of twenty-five hundred years of Buddhist culture, and as the guest of a distinguished Japanese family, I found myself in a bind. I wanted to express the equality of men and women. I wanted to support Shunko-san’s efforts and those of all women in this male-dominated institution. However, I knew straying too far from the protocol would have caused embarrassment to my host family. This is a feminist’s dilemma—how to find your authentic place in a male-dominated environment. Do you follow the lead of women who have survived through submission? Do you risk your precious place for a single statement of equality?

What brings out your principles? How do you decide when to stand up and when to back down?

We each need to find a way to fulfill our ideals and to respect some of the different values. I found it easier to make the point because Shunko-san was involved. I wanted to stand up for another who was being put down. I became a little taller and a little stronger by relying on awareness of the moment in a larger context.

What brings out your principles? How do you decide when to stand up and when to back down? Surely there are moments for each of us—moments when we want to fit in with a group but feel that something is amiss. Take your breath, settle your mind, and listen to the amplified awareness in your body. What is at stake and what are the consequences? Being embarrassed, while weighty, doesn’t carry the same consequences as, say, being arrested. Choose wisely with a realistic view of consequences.

In the context of today’s women’s marches, it is good for us to remember that twenty-five hundred years ago, Mahapajapati, the Buddha’s aunt and stepmother, led the first women’s march. She stood her ground against her powerful stepson (Buddha), the leader of the religious order she wished to join. For the sake of the women she taught, she risked everything. The Buddha had cautioned her to not set her heart on women’s ordination. But she persisted. She led a 150-mile march, with barefoot nun aspirants, to appeal to the Buddha for female ordination. She took a radical stance and action without which we might not have women accepted as Buddhist nuns today. I bow down to Mahapajapati, who fought for women’s ordination and directly affected my own life. Her strength and courageous actions affect Buddhism across more than twenty-five hundred years. We need to remember that our decision to stand up for an ideal can matter more than we can realize in any moment.

Share

Related Books