Radhule Weininger

RADHULE WEININGER, MD, PHD, is a clinical psychologist, psychotherapist, and meditation teacher. She leads weekly and monthly meditation groups in Santa Barbara and leads retreats in both the United States and internationally at La Casa de Maria Retreat Center, Spirit Rock, Insight LA, the Esalen Institute, the Garrison Institute, and she is the author of Heartwork: The Path of Self-Compassion.

Radhule Weininger

-

Heart Medicine$18.95- Paperback

Heart Medicine$18.95- PaperbackBy Radhule Weininger

Contributions by Joanna Macy

Contributions by H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Foreword by H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Foreword by Joanna Macy

GUIDES

Being Mindful of Body, Thoughts, and Feelings | Heart Medicine

An Excerpt from Heart Medicine by Radhule Weininger

As we encounter difficulties, mindfulness is crucial: it allows us to be present, here and now, with nonjudgmental, moment-by-moment attention. Penetrating a LRPP [Long-standing, Recurrent, Painful Pattern] with mindfulness dissolves the LRPP’s power source and creates opportunity for profound change. The energy that has been trapped by our entanglement with a LRPP is released and transformed into awareness and wisdom.

The practice of mindfulness is a form of “awaring,” or applying moment-by-moment awareness with a nonjudgmental attitude to whatever we are experiencing in each instant. Awaring is the process-oriented verb form of awareness. By comparison, the field of awareness, out of which everything arises and falls back, can be seen as the noun form. Self-awareness is awaring or being mindful of ourselves and our inner experience, while meta-awareness extends our mindfulness to include our environment and the relationships with which we are engaged. With both the self-awareness and meta-awareness aspects of mindfulness, we are now able to address our LRPPs.

Through the practice of mindfulness, we learn how to be present and how to notice when we are not present, which usually means our mind is somewhere else—thinking, ruminating, or worrying about the future or the past. When we are mindful, we learn to let go of the habit of ongoing distraction through external stimuli. We contact an inner sense of balance and calm and begin to realize that it is possible to return to this refuge of steadiness, quietude, contentment, and ease. Body, breath, thoughts, and feelings become infused with the oxygen of awareness, and our LRPPs can no longer constellate in the same way. As we learn to observe the process of getting LRPPed as it unfolds, we become less reactive. Gradually, our ancient configurations dissolve and, over time, may even disappear.

Turning Our Gaze Inward

When we feel out of balance, it may feel counterintuitive simply to sit still, be quiet, and look inward. Usually we try to distract ourselves with a pleasurable activity—anything that will take our mind off our painful feelings or difficulties. But mindfulness meditation is a courageous step toward focusing on what is going on inside. As we become aware of ourselves, we’ll notice how our body, mind, and heart feel. We always have a choice: either to run away from an unpleasant experience by distracting ourselves or to confront the truth of our experience by becoming mindfully present.

Contacting the Felt Sense of the Body

Bringing our attention to the felt sense means becoming aware of how particular physical sensations express what’s going on in our bodies, thoughts, and feelings. The following guided meditation can be helpful in attuning to the felt sense. Please read through all the steps first before going through them. Most of the practices in this and later steps are meditative in nature.

FEELING THE FELT SENSE PRACTICE

3–5 minutes

- Sit comfortably, turn your gaze inward, and become aware of your inner landscape.

- What sensations are you aware of in your body? Stay with that feeling for a while.

- Be aware of the sensations around your face. For example, perhaps there is tightness in your jaw or around your eyes. Stay with that feeling for a while.

- Notice if there is tightness in your neck and shoulders, your belly, arms, or legs.

- Begin to fill your whole body with awareness.

- Become aware of each sensation with kind curiosity.

- Whenever you notice you’ve become distracted, kindly lead yourself back to the sensations within your body.

- Acknowledge yourself for having noticed that you were distracted and for your ability to return to your present experience.

Listen to the Guided Meditation

Coming into Relaxed Alertness

Being mindful of the physical sensations in our bodies helps us to connect with the present moment and brings us into relaxed alertness. When we sink beneath the turbulent waves of our thoughts, we can find an underlying sense of calm, peace, and relaxation. This felt sense of the present moment is often experienced as a refuge, a point of balance and ease. Learning to regularly drop into this awareness lowers our baseline level of agitation, anxiety, and stress.

To work toward relaxed alertness, follow this brief body scan exercise.

BEING IN THE NOW PRACTICE

4 minutes

- Notice the felt sense of your body touching the chair, the cushion, the ground.

- Notice the muscles in your face relaxing, the muscles around your eyes softening, your jaw dropping.

- Feel your shoulders letting go and your arms and hands letting go of any tension they might be holding.

- Now bring your attention to the center of your chest, your heart, and feel your breath flow ever so gently.

- Be aware of rawness, ache, numbness, or vibration you might be feeling at the center of your chest.

- As you feel your belly, you might notice it softening.

- Sense the sensitive skin on the back of your body, guiding your attention very carefully, inch by inch, from your toes to your head.

- Feel your buttocks touching the chair and supporting your trunk and the base of your spine.

- Be aware of your arms, your legs, your entire body filling up with presence.

- Feel your body as a whole, every inch of your body becoming alive and aware.

- Then feel the surface and the inside of your entire body filled with consciousness and wakefulness.

- Linger on this sensation while being fully aware of your whole body sensing itself deeply.

- You have arrived in the NOW.

Listen to the Guided Meditation

Attuning to the Natural Breath

In learning to be mindful, it is helpful to attune to the subtle sensations of the natural breath. With very refined attention, we can contact the felt sense of its every movement. The natural breath is the uncontrived breath, the breath that is not controlled or managed in any way. Following the sensations and movements of breath moment by moment can lead to a deep state of concentration. The Buddha himself is said to have reached enlightenment through the practice of mindfulness of breathing. As we attune to our breath, our thinking mind calms down and relaxation naturally descends over us. We are learning to allow our body to be breathed and for breath to breathe us, letting our awareness and breath flow together in a relaxed and spontaneous way.

To practice mindfulness of breathing, please follow this guided meditation.

MINDFULNESS OF BREATHING PRACTICE

4 minutes

- Let yourself settle into the sensations of your body, sensing the touch points where your body meets the chair, cushion, or ground.

- Feel the entirety of your body and allow it to be filled with consciousness and wakefulness.

- From this field of body awareness, feel your breath arising naturally by following its sensations and movement.

- Be aware of every instant of your body breathing, every moment of your in-breath and every moment of your out-breath.

- Intensify your focus to every instant of breathing without getting tense, while remaining completely relaxed.

- Without controlling or managing your breath, follow your natural breath. Surrender to your body being breathed, your breath breathing you.

Listen to the Guided Meditation

Share

Related Books

A Healing Power

by Radhule Weininger, author of Heartwork

A Surprising Discovery

Recently, during a one-year mindfulness facilitator training, our team of teachers made a surprising discovery. As part of an exercise, students were taught how to guide each other through mindfulness and compassion meditations. Afterwards, students shared their experiences of how this had been for them. One of those who shared was Anne. She told us that this exercise had helped her to understand the depth and subtlety of the mindfulness of breathing practice more deeply and enabled her to feel in a tender way her meditation partner Cloe’s sorrow. While we were pleased to hear this, we were not surprised. This is what we had been hoping for. However, what she shared next took us by surprise. She spoke of an “unexpected great joy” this process had given her, and, in her course evaluation shortly afterwards, described this as “the single best exercise in the training.” This was not only true for Anne; most everybody in our thirty-member strong group shared similar reactions to doing this exercise.

The Bodhicitta Effect

Bodhicitta is the wish for all beings to be well, to be happy, and to be free. Even our wish for own awakening is dedicated to the well-being of all. Bodhicitta is regarded as the jewel in the crown of Mahayana Buddhist practices. When we act on our wish to share our riches, such as knowledge, insight, happiness, or wealth with others who are less fortunate, we are acting with the motivation of Bodhicitta. As we act with the intention to help another to be more at ease, awake, and healthy, we notice that we ourselves become happier and increasingly content. At the same time, we notice a growing desire to continue working for the well-being of others. Our longing for connection, and to see another well and happy, becomes intertwined with our own happiness, meaning, and purpose. This is the “Bodhichitta effect.”

Bodhicitta is the wish for all beings to be well, to be happy, and to be free. Even our wish for own awakening is dedicated to the well-being of all.

Learning, Growing, and Receiving through Teaching

Currently, mindfulness teachers Jack Kornfield and Tara Brach are training about two thousand students to become facilitators. Their training is only one of many current mindfulness teacher trainings. What is it that draws so many to want to share their practice with others?

When we learn to teach, we don’t just do this practice of meditation for our own benefit but also for the benefit of others. As we deepen our practice of meditation and experience it more fully, our hearts open to those we guide, and compassion develops naturally.

Many years ago, when I began leading others in meditation, I realized that my understanding and experience of the practice was deepening, and that my heart was becoming naturally gentler and kinder. Talking with Jack Kornfield, my mentor of many years, about this, he smiled and said, “Yes, when you teach others, it works your own heart.”

I remember a phrase from my medical training, “Learn one, do one, teach one.” If we “learn” and “do” the practices of mindfulness, loving-kindness and compassion, then “teaching” others helps to open our own heart even more.

I remember a phrase from my medical training, “Learn one, do one, teach one.” If we “learn” and “do” the practices of mindfulness, loving-kindness and compassion, then “teaching” others helps to open our own heart even more.

The Healing Power of Caring and Sharing

What is happening here? Is this about the benefits of giving? Or is it about what happens when we go beyond just caring for our own well-being?

There has been extensive research on how giving makes us happier than receiving. Social scientist Liz Dunn writes in the journal Science that people’s sense of happiness is greater when they spend relatively more on others than on themselves. The Huffington Post reported a study on charitable giving. They found that when people donated to a worthy cause, the midbrain, an area related to pleasure, lit up.

Emphasizing the Buddhist principle of dependent co-arising, the Dalai Lama says that one’s own happiness is dependent on the happiness of others. In Ethics for the New Millennium he notes that happiness comes from a deep and genuine concern for others. The Dalai Lama calls giving to others, “wise-selfish,” because in the end, we gain as well. Mahatma Gandhi said, “The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service to others.” Will we have to transform the idea of “self-help” from “me-help” into “we-help?”

If we understand that our giving, sharing, and passing on makes us happier and opens our hearts, then doing it begins to feel natural to us. So often we are taught that in order to be happy, we need to give priority to taking care of ourselves and, perhaps, also a very few near and dear ones. Even some Buddhist groups teach that we should contain ourselves to “sweeping our own door-steps.” But research tells us how important it is to share with others so that we feel happier, less afraid, less alone, and more empowered.

Arthur Brooks from Syracuse University pointed out that “givers” are happier and healthier than those who don’t. Stephen Post and Jill Neimark claimed in their book, Why Good Things Happen to Good People, that giving to others benefits the community and is therefore associated with pleasure and happiness. They also noted that compassion and kindness leave less room for negative emotions.

Giving to others releases “feel-good neurotransmitters,” and leads us to the self-reinforcing, yet virtuous cycle of a “helper’s high.” Sander van der Linden from the London School of Economics suggests that “giving” points to a solid internal code of conduct, which in turn is a strong psychosocial predictor of charitable intentions. This dynamic naturally leads to self-confidence, self-esteem, and resilience.

Practicing Interdependence

The Buddha’s central teaching is that the true nature of life is interdependence. Could it be that when we choose an activity with the intention of helping another, when we deliberately “practice interdependence,” that this brings us into alignment with “the way things are,” and that this brings us joy? Does happiness emerge spontaneously and organically when we practice interdependence?

The Bodhicitta Effect implies that our happiness, confidence, and sense of meaning are interwoven with our willingness and ability to share our knowledge, wisdom, and kindness with others. This is not only true of teaching meditation to others but to the generous and compassionate quality of every act of kindness.

The Bodhicitta Effect implies that our happiness, confidence, and sense of meaning are interwoven with our willingness and ability to share our knowledge, wisdom, and kindness with others.

I remember Peter, another student in our training, who had complained many times of how “numb” he felt throughout the months of our time together. In the closing circle, Peter spoke of how he had experienced empathy in a new and caring way for Stuart, whom he had been guiding.

There are many ways to share and serve. Teaching meditation is a way to practice compassionate action that allows us to grow and deepen in the process. And it does not matter whether we are guiding just one other person, or two neighbors, or a bigger group in meditation—the Bodhicitta Effect is activated.

Related Books

The Jewel Ornament of Liberation

$39.95 - Paperback

By: Khenmo Trinlay Chodron & Gampopa & Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche

From Fire to Mud | A Journey Through the California Fires

The Lotus of Mutual Belonging

by Radhule Weininger, author of Heartwork

“If the world is to be healed through human effort, I am convinced it will be by ordinary people, people whose love for life is even greater than their fear. People who can open to the web that called us into being.”—Joanna Macy

The Flames of the California Fires

From the top of our roofs we could see the fires crawling over the hills closer and closer towards us. In December 2017, Santa Barbara was stricken by the most significant fires on the West Coast of America. For about two weeks, our little town felt like a post-apocalyptic landscape, deserted, with shops closed and scattered people wearing facemasks and shawls, scurrying through the deserted streets. Thrown back and forth between terror of annihilation and detached numbness, many of us hunkered down at home glued to the TV screens or fled town.

The Santa Barbara fire followed closely on the heels of catastrophic burns in California and hurricanes in other parts of the country as well as environmental distress spreading throughout the world, from Puerto Rico and Mexico to Bangladesh. Our fire flared against the backdrop of a harrowing year in the political and social arena. Environmental protections had been stripped away as well as healthcare, respectful treatment of immigrants, quality education, and human rights.

In the midst of the desolation of the fire crisis, when many of us felt contracted, lonely, and shrunken, the yellow-clad bodhisattvas had rolled in on their red chariots. Youthful, strong firemen and women faced the inferno on all of our behalf. Their willingness to give, to risk it all for our townspeople, saved not only countless lives and houses but also momentarily restored trust in the goodness and generosity of life. One of the bodhisattvas, a 31-year-old man, father of a young girl, tragically lost his life in the fire. His willingness to give up everything to save others softened our hearts.

Another Catastrophe

Who would have dreamt that three weeks later, as we were beginning to heal from the fire, rains would come to devastate the fire zone with a mudslide? No one was prepared for this catastrophe. After the fire and before the flood there was a strangely surreal hiatus between tragedies. For a few days we were inspired by the compassion and courage of others, and we tried to believe that all was normal again. It was surprising how we seemed to rebound when the flames had receded just days before the holidays. We took on Christmas with gusto; we shopped away and cooked up a storm while trying to forget the recent calamity. Yet, a strange sense of hollowness and unreality remained. I found within myself a nagging sense of unease. Caring only for ourselves and our near and dear ones did not seem enough.

Yet, a strange sense of hollowness and unreality remained. I found within myself a nagging sense of unease. Caring only for ourselves and our near and dear ones did not seem enough.

Right after New Year’s, when the rains descended, the mountain moved, and immense masses of rocks and mud slid down to decimate our town. A gargantuan rain and mudslide left a significant area destroyed, hundreds of houses demolished or damaged, and over twenty people dead. Several victims have still not been found. Overwhelmed with emotions, many of us wondered if we were experiencing a preview of a nightmare future. We experienced ourselves as vulnerable, little creatures, easy to hurt, if not extinguish. We felt the vulnerability of our broader world. While the immense rocks tumbled down the mountains, our hearts cracked wide open. With so many human lives lost, our community was devastated, and because so many were displaced, those of us remaining were brought together by our tears.

The Stories

We were broken open to one another by amazing stories of human bravery and generosity. Curtis, a local man, stayed behind intentionally, so he and his neighbor could help all the other people on his street get out of their houses and into safety. Connor, a twenty-two-year-old friend of my kids from school, tried in vain to pull his dad out of the stream of mud. A young firefighter risked his own life to dislodge a family of five and their dog from their destroyed house: to lift them, one by one, into a helicopter. The family, who had lost their father, received generous donations from a GoFundMe collection; they gave the whole sum to an underprivileged immigrant family, a father and his two-year-old son, who had lost their mom and siblings in the stream of sludge and boulders. Hearing about these and many other examples of selfless and compassionate action freed us from isolation, and, for a brief time, allowed us to know the web that called us into being to remember that we “inter-are.”

As much as I wished that this catastrophe had never happened, at the same time I appreciated what we were learning. I began to worry that our open hearts would close up again. I recognized that the events here were a microcosm of what is happening on a global level. We had been catapulted into what may well be our future, a future foreshadowed by what is already happening in many other parts of our world. As humans we are pulled between closing up and self-protection on the one hand and openness towards others and generosity on the other. This is a fundamental dynamic for all of us as we face difficult times.

As much as I wished that this catastrophe had never happened, at the same time I appreciated what we were learning. I began to worry that our open hearts would close up again. I recognized that the events here were a microcosm of what is happening on a global level. We had been catapulted into what may well be our future, a future foreshadowed by what is already happening in many other parts of our world. As humans we are pulled between closing up and self-protection on the one hand and openness towards others and generosity on the other. This is a fundamental dynamic for all of us as we face difficult times.

In his best seller, Why Buddhism is True, developmental biologist Robert Wright argues that over the millennia it may have been to our evolutionary advantage to be greedy, selfish, and “delusional” in our perception of ourselves and reality. Boosting up our egos and grasping whatever we could for ourselves may have advanced our family’s or tribe’s position. Now this kind of behavior is threatening the survival of our ecosystem, and it brings the gravest suffering to many parts of our world. Wright has a recommendation for us: as genetic evolution is too slow to save us now, we need to engage in cultural evolution; meaning, we need to cultivate attitudes that help our societies to transform and our planet to survive and heal.

The Buddha’s Idea of Dependent Co-Arising

As I contemplate that which might support us in holding our experience in a more caring and respectful way, I think of a phrase I heard recently from Joanna Macy: “mutual belonging.” She used this term in her explanation of the ancient Buddhist idea of dependent co-arising. The Buddha saw life as continuously emerging and then falling back into the stream of becoming. He showed us how everything co-arises in interaction. The reality we experience ascends from what we bring to it, our intention, effort, mood, and awareness. Life is changing as we participate in it. Training in understanding of dependent co-arising helps us to cultivate attitudes of caring towards a widening circle of others. As our caring widens, our perceptions and behaviors change, allowing us to develop more compassionate ways of being with each other and our world.

The Buddha taught that we suffer deeply when we stay imprisoned in a “delusion of separateness.” As we remain stuck in fear and alienation and as we cling to what by nature is transient, we become more and more entrapped. I see this with some of my psychotherapy clients. Those who have been so frightened by life that they have retreated into a shell of self-protection find themselves cut off from the stream of life. They often suffer the secondary trauma of isolation, quiet and desolate anxiety, and loneliness. By contrast, I have seen that it is possible to free ourselves by living our true nature, that of inter-being, joining the dynamic of life itself. Awareness of our interconnectedness as well as the fact that we all affect each other in everything we do can then become the basis for a dynamic bridge-making between ethics and metaphysics. If we cultivate attitudes of being that help us abstain from violence, greed, and self-preoccupation and instead practice awareness, kindness, and caring for all life, then our own suffering and that of others will spontaneously decrease.

Practically speaking, how can we engage in Wright’s cultural evolution? How can we here in Santa Barbara remember Joanna Macy’s call to practice our radical interconnectedness with all of life? How can we cultivate attitudes that help our societies transform and our planet to survive and heal?

Practically speaking, how can we engage in Wright’s cultural evolution? How can we here in Santa Barbara remember Joanna Macy’s call to practice our radical interconnectedness with all of life? How can we cultivate attitudes that help our societies transform and our planet to survive and heal?

The “Solidarity and Compassion Project”

A little over a year ago, in response to feeling overwhelmed and despondent in the wake of the presidential election, my husband, physician and author Michael Kearney and I initiated monthly community meetings called the “Solidarity and Compassion Project.” In each meeting, we addressed a different theme and invited a panel of speakers, representing a range of spiritual, intellectual, scientific, and psychological perspectives to join us for practice and discussion. Poets and musicians also joined us as we learned that joy is the much-needed antidote to despair and grief. Each meeting combined meditation with an exploration of sustainable ways to bring compassion and engagement to the many social, political, and environmental challenges we are confronting.

Serendipitously, in December, before the fire and mud, we had planned that the theme of our January gathering would be about grief. Meeting in the belly of an old church with richly colored windows allowed us to exhale after we had held our tension in so tightly during the weeks of fire, downpours, and rolling mountains of sludge. Guided meditations allowed us to be present with our inner feelings of rawness, dread, and alarm, as well as continuous feelings of uncertainty. Michael and I led participants in loving awareness and mindfulness practices with phrases, such as “Let yourself settle into the sensations in your body, and notice whether there is tightness, ache, or vibration. Feel breath arising with the inhale, letting go with the exhale, allowing the warm breath of life to breathe you.”

We also led the group in compassion practice, inviting all to extend caring to themselves and others in a gentle and relevant way. I suggested that those gathered quietly repeat the phrases I offered. I said, “May I treat myself with gentleness and understanding in this time of loss. May I meet my grief with tenderness and care,” and, “May I be compassionate and patient with myself, especially when I feel afraid.” Widening the circle to include others in our care, I continued, “May those close to us be healthy and protected. May all those who were hurt in this crisis be safe well again,” and, “May those in this world who experienced similar traumas to ours find the support they need to heal.”

Finally, we began to relax. Together we were able to feel the feelings of last week’s experiences. Images arose of burning mountains and memories of the alarming voices of TV announcers shouting their warnings. We remembered the dark grey air, the torn apart houses, the mud-covered areas that had once been streets; we remembered the faces of those dead or missing. Within the safety of community and practice, we were also able to feel the sensations of our stressed nerves, so raw and fried. Feelings, thoughts, and image debris were released within the safety created by this practice of mindfulness meditation—all passing down a river of loving awareness.

When we feel afraid, lost, and trapped within ourselves, practicing self-compassion can reaffirm our willingness to extend a hand towards our own traumatized inner selves. As we gradually make friends with ourselves, compassion for others will follow more easily.

When we feel afraid, lost, and trapped within ourselves, practicing self-compassion can reaffirm our willingness to extend a hand towards our own traumatized inner selves. As we gradually make friends with ourselves, compassion for others will follow more easily. We extended warmth and understanding towards that in ourselves which was afraid and lost; we thawed out the cold spaces within and around our hearts. It felt as if the cores of our beings had contracted in the midst of so much agitation and panic. Like shy birds with their heads pulled in, we needed breath to breathe us into calm, warmth, and tenderness. Then, we sat together for a long time, sharing what we’d been through, remembering Curtis, Conner, and the young fireman. Through love and developing equanimity, we began to learn to tolerate the rawness of our experiences. My husband Michael puts it like this: “The more connected we are, the more we care. The more we care, the more we long to do what we can to improve the well-being of others. And in that process, we heal.”

In recent weeks, groups of volunteers of all ages and of all parts of the community, the “bucket brigades,” emerged. These groups of community volunteers have gathered every weekend and moved “bucket by bucket,” restoring damaged homes and landscapes. One young woman, Anahita, who lost a close friend in the mudslide, shared in one of our gatherings, “At first I felt more triggered than anticipated by seeing all the mud and debris. It reminded me of our friend who died, and I felt like I had more of a tangible visual and tactile feel for how she lost her life. But as I connected to the people and the mission of the bucket brigade, and as we picked up our shawls and started slowly chipping away, I felt a sense of healing in this. Tears welled up in my eyes—tears not only of grief but also of gratitude, for community healing in action.”

Dealing with Catastrophe

Catastrophic events challenge us to find new ways to reintegrate our psyches. I am grappling with unanswered questions: What do we learn from such events? Do we go back to “business as usual,” trying to forget as fast as we can? As research on groups of people threatened with annihilation suggests, will we close up, become more rigid, look for scapegoats, and turn our grief into blame? Or can our hearts stay open and soft with increased compassion for others who suffer through similar plights?

A few weeks after our first gathering, I led a meditation in Montecito, in the area that had been most devastated by the mudslide. Huddled together in a yurt-like structure behind a store, in what is called the “Sacred Space,” fifty people came to meditate together, listen to stories of loss and trauma, of uncertainty, fear, and hope. A man told us about the anxiety that still wakes him up every morning at 3 a.m. A woman talked about how she found gratitude for what is truly essential in her life after her house had been completely flushed away. There was a raw and open feeling in the room.

Recently, I heard that there are lawsuits looming in Santa Barbara, some devastated residents blaming others as culprits for nature’s disaster. What is happening in our little town is mirrored by the developments in our country where we face daily choices between angry blame and proactive compassion. Experiencing the mudslide brought out a whole spectrum of responses. Some have found themselves retreating into understandable behaviors of self-protection, while others have turned towards initiatives leading them to reach out in generosity. A grocery store and several restaurants at the edge of the disaster zone opened their doors to give free water and meals to survivors and first responders.

How do we turn adversity into an opportunity to grow and love and heal? Holding this question, I was reminded of the well-known American Indian story “Which Wolf do we Feed?” This is the version told by Algonquin elder Wolf Wahpepah:

You probably heard the story of the Indian boy who went to his grandfather for wisdom. His grandfather told him, “Inside of me there are two wolves, a selfish wolf and a compassionate wolf. And they fight all the time. The selfish wolf tells me to look out for myself, to feed my appetite. The compassionate wolf says I should be concerned about the welfare of all and be concerned about their needs.” The grandson asked his grandfather, “Well grandfather, which one of the wolves wins?” Grandfather replied, “Whichever one we feed.”

This article is about practice, choice, and cultivating an attitude of compassion and caring. We need to develop structures that are based on an understanding of interdependence and inter-being, that recognize our mutual belonging and radical interconnectivity. Gradually, as we align ourselves one by one with these structures of mutual belonging, we create a culture of compassion and spontaneous caring.

What has happened in this tiny microcosm of Santa Barbara might have significance in a much broader context. As we get thrown about by increasingly intense environmental events, as resources for many are getting slimmer, and as our weapons of mass destruction become increasingly ominous, we in our broader world need to cultivate what we are learning in Santa Barbara. We need to teach ourselves to be generous, open-hearted, and inclusive.

Related Books

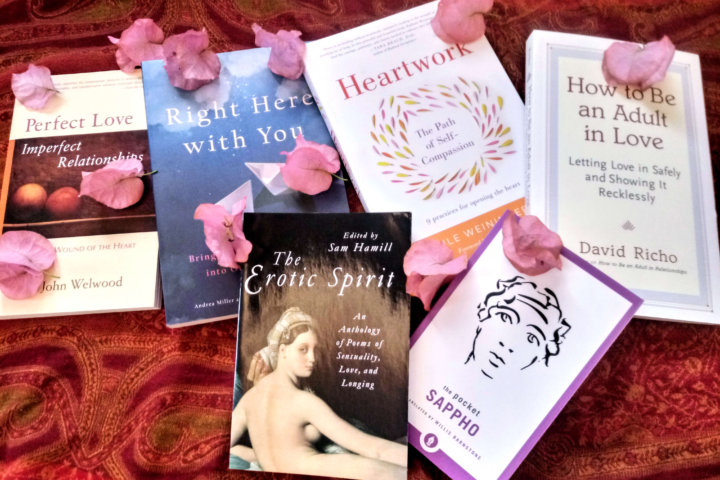

What to Read this Valentine’s Day

by Lindsay Michko

Whether you’re single, in relationship, or “it’s complicated,” February 14th is a day of super-charged emotions: the bliss of being in love, the pangs of loneliness, the bittersweet imperfections of relationship, and everything in between. Regardless of where you fall on this spectrum, the following titles are sure to heighten your Valentine’s Day.

For the Poet

“Love shook my heart like wind / on a mountain punishing oak trees” (Eros, p. 40) Fragments though they may be, Sappho’s musings on desire, love, and intimacy are timeless and evocative, continuing to inspire new readers with each generation. Much of what survives of Sappho’s writing is love poems to women. Unfortunately, throughout much of history, Sappho’s work has fallen victim to misogyny, with commentators and critics attempting to explain away the homoerotic content as spiritual metaphor. Today, Sappho is a celebrated lesbian voice whose writings “contain the first Western examples of ecstasy, including the sublime” (xlvi). Whether describing ecstasy or agony, Sappho’s poems strike a universal chord. At some point, we have all pleaded with the goddess of love in one way or another. “On your dappled throne eternal Afroditi, / cunning daughter of Zeus, / I beg you, do not crush my heart / with pain, O lady…” (Prayer to Afroditi, p. 3).

The Erotic Spirit: An Anthology of Poems of Sensuality, Love, and Longing

edited by Sam Hamill

In this anthology, editor Sam Hamill demonstrates the universal nature of poetic and spiritual contemplation of erotic love, presenting a collection of poetry spanning thirty centuries and the entire globe. “But how to know the self-indulgent desires of the flesh from the truest spiritual connections that transcend selfish impulses?” Hamill muses. “Poets have wrestled with this equation since the dawn of language. One way to attempt resolution is to explore poetry of the erotic spirit as a handbook, a guidebook for care of the lover’s soul.” This is the ideal poetry collection for those who rejoice in the divine aspects of romantic love.

For the Wounded

In order to fully love others, we must learn to love ourselves. In Heartwork, Radhule Weininger offers meditations and practices to cultivate self-compassion, which “allows your heart to heal and lets you include others in your care” (xviii). Journal prompts at the end of each chapter create space for reflection, and accounts of Weininger’s and others’ healing journeys provide inspiration and encouragement. Anyone wishing to work with their vulnerability and emotional resilience will find this book to be invaluable in deepening relationships—starting, of course, with the self.

Perfect Love, Imperfect Relationships: Healing the Wound of the Heart

by John Welwood

Here, author John Welwood offers a psychological perspective on our human yearning for love and the sources of disharmony we experience in relationships. Welwood helps readers address their own psychological wounds preventing them from loving and receiving love fully. Practical exercises encourage readers to explore their emotions and expectations more closely, to gain valuable insight into cultivating a healthier relationship with intimate love.

For the Partnered

Right Here With You: Bringing Mindful Awareness to Our Relationships

edited by Andrea Miller and the editors of the Shambhala Sun (now Lion’s Roar)

This anthology of essays offers invaluable insight on how we can bring more awareness to the various stages of loving relationships, from a variety of perspectives. Those looking to be more present for their partner, strengthen communication, or open up their hearts will find great benefit in this collection of essays from teachers and writers including Thich Nhat Hanh, Rabbi Harold Kushner, the Dalai Lama, and many others.

How to Be an Adult in Love: Letting Love in Safely and Showing it Recklessly

by David Richo

Offering a combination of psychological and spiritual wisdom, author Dave Richo helps readers to bring more clarity and maturity to loving relationships. Richo explores the many forms love can take and emphasizes the importance of loving oneself and understanding one’s need for love. Each chapter contains practices and exercises to gain deeper insight. Whether single or partnered, readers will benefit from becoming more mindfully fearless in relationships.

May these books be of benefit, helping us all to remember the depth of our capacity to love ourselves and each other, not just today, but every day. Love may not always feel like a strength or a blessing, but these titles remind us to celebrate and learn from it, in its many manifestations.