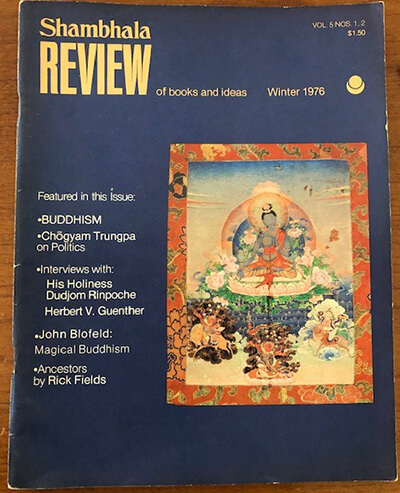

This article on Buddhism and Politics originally appeared in the Shambhala Review of Books and Ideas, Vol 5, Winter 1976. It in included in the Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa, Volume 8.

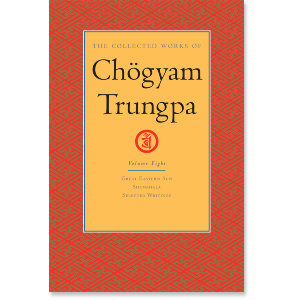

The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Eight

$59.95 - Hardcover

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche: In this country we have the particular problem that we have inherited a lot of things, and even though we want to understand them properly and do the proper thing, still, there are so many extraneous things we have to work through. This makes it somewhat difficult. Generally it is a question of having a sense of responsibility to society. This seems to be the important thing. People involved with a spiritual discipline have a tendency to want nothing to do with their ordinary life; they regard politics as something secular and undesirable, dirty or something. So, to begin with, if a person came with a sense of responsibility to society, that would be a Buddhist approach to politics and also to the social side of life, which is the same, in a sense. There should be a sense of one’s own responsibility, not relying on other people’s help. One’s own economic situation should be self-sufficient; a sense of responsibility begins there. I think one of the problems is that the abstract notion of democracy is misleading. In some sense, a lot of the problem comes from the aggression inherent in our concept of democracy; people begin to feel they have been cheated or have not been allowed enough freedom to do what they want, to say what they want. It lacks a notion of discipline that should go along with it: just throw everything into the big garbage pail and, hopefully, somebody will do the sorting out in our favor. This is a big problem. I think the Buddhist idea of a politician is not so much one of a con man or of a businessman who wins favor with everybody, but someone who simply does what is necessary. Sometimes the situation is such that you have to go through undesirable experiences, even give up your sense of freedom. Sometimes you may even have to allow yourself to step back. I think in this country, politics are based on a kind of bad-mouthing and trying to speak out, which is all right, but which usually amounts to not knowing what to say; one is just copying someone else’s aggression. Then aggression starts to snowball. In some sense, the main point is responsibility, which is important in how the government is run, how the situation is organized (not just ignoring everything completely and regarding it as a bad job). I mean, from a Buddhist point of view, there is some sense of taking an interest, we could say, for the sake of all sentient beings. This means we should take part in it. This does not mean to say you have to take part in riots or blowing up banks or anything like that. But it means to undertake some kind of process whereby you try as much as possible to at least eliminate the byproducts that you inherit. When you begin to do this, then you begin to have a feeling that a fresh start is taking place.

SR: The byproducts are . . . ?

Rinpoche: Our long-term inheritance from problems that took place before and of which we are still victims. Trying to change this karmic chain reaction. Just start fresh.

SR: You are talking about responsibility on a personal level, an individual level, not as a group.

Rinpoche: Yes. I think the notion of a group is very misleading. There is no such thing as a group, actually, but putting individuals together is what makes a group. So it depends on whether the individuals are strong. That is precisely the Buddhist notion of sangha.

SR: An incident took place during the Vietnam war that was very surprising to most Westerners and perhaps to Buddhists in particular. I don’t know if you remember it or not, but a young monk committed suicide by setting fire to himself; he poured gasoline over himself and then lit a match. He did this as a political protest. It was very surprising to most Westerners, and even to Western Buddhists. Do you remember that incident?

Rinpoche: Yes, indeed I do. I read a book about it. I was in England at the time.

SR: Can this be explained in a Buddhist context?

Rinpoche: Well, I don’t think you could. I would not say it was a truly Buddhistic kind of approach but rather more of a Southeast Asian or Oriental mentality, like the hunger strikes in India, more of a national characteristic. For instance, there was a big protest of the Koreans who cut off their fingers in front of the Japanese embassy. This is traditional rather than Buddhist. And it really doesn’t help anything. You just become a headline in the newspaper for several days and then the whole thing is forgotten. So, I would not say that this is a particularly Buddhist approach. Obviously, those Buddhists had suffered a lot and felt tremendous pain and discomfort, but nevertheless, they could have done something different.

SR: So we have these two extremes. On the one hand we have those who take a violent approach to politics and either blow up banks or commit acts of violence; and on the other hand, we have personal acts of violence to oneself, like this monk. If neither of these is the proper approach—and the proper approach, from what you have indicated, is not passive and is on the individual level—what sort of approach is it? Would you go into this some more?

Rinpoche: Yes. We use the terms passive and active. We have to be very careful. Active does not mean aggressive, just active. In a sense, it is a sort of passive activity, more of a reconstruction of new situations rather than riots or things of that nature. If each person, in his own capacity, contributes a little bit by having a very sane approach, first of all, to his own personal life, which should be straightened out, then his sense of sanity could be developed. It might be just a drop in the ocean, but it would be very valuable. Start in this way and at the same time pay attention to what is happening and see how you can contribute.

SR: This is a bicentennial year as well as an election year. People will be going to the polls in November to elect a new president, new congressmen, and in a great many states governors as well. And since politics are never black or white, and you can never find just exactly what you would like to vote for, is there, from a Buddhist standpoint, a way to prepare yourself when you go to the polls to make these difficult decisions?

Rinpoche: Well, I think even if you had a most enlightened president, things still wouldn’t be different, because he too inherits the political setup and economic traditions of the country. So he also is trapped in a particular chain reaction. You can’t have an ideal situation. I suppose the best approach is a long-term approach; taking it in stages, like hinayana, mahayana, and vajrayana: a slow approach. It is similar to trying to shift gears into some kind of element of sanity that exists in your particular realm, your particular congressman or president, and trying to follow it up. It is not so much what we should be doing this year alone but that we should follow it up all the time, trying to develop some trend of continuity in a different direction, rather than purely believing that there is going to be tremendous good news if the right president is elected. Somehow, that is not going to work. It takes the work of centuries. But I think it is possible; it is up to people to change, to take part and pay attention, if they can do so.

SR: Do you foresee Buddhism taking a more public role in politics? Do you see it influencing politics?

Rinpoche: Well, I think we cannot say that we are planning on having an active role in politics. The decision is not up to us. However, this might happen as more and more people become involved in Buddhism, especially as intellectuals and influential people begin to be slowly attracted to the Buddhist approach. So it is a question of sheer numbers. Because of their own life situation, I think in quite a short time, perhaps, Buddhists will have a visible effect on politics. And the effect will be great, and they will find themselves playing a part in politics, rather than just jumping in. So it could happen.

SR: Do you see anything in particular happening as a result of this?

Rinpoche: Well, hopefully some kind of sanity would develop, obviously. We can’t expect a golden age. On the one hand, if we have a long period of time without a war, everyone will be affected by a depression; and on the other hand, if we have a long period of an economic high, everyone will just abuse himself completely. Some kind of turmoil is necessary, but we do not particularly have to develop it. It happens. At the same time I think the Buddhist contribution to these situations would be very different in that the Buddhist approach is nontheistic. It does not have a concept of uniformity, particularly—just basic unity. And because of this, there is no hierarchy, like a belief in God. Therefore, since everything is self-reliance, purely self-reliance, that does encourage people to think more for themselves. In time that would have a great effect, I would say.

SR: Christianity, more or less, has been a religion of a future life. In other words, life here is very ephemeral and we are here only in order to prepare ourselves for another life, a greater life, which comes after death. This has influenced the social concepts of the West to a great extent. A great deal of social evolution didn’t take place because the attitude was to keep to the status quo since this life was not supposed to be improved; you are supposed to accept it as God’s will in order for you to prepare yourself for the life to come. Am I correct in saying that Buddhism does not have this sort of attitude toward life? That this life is only preparatory for another?

Rinpoche: Well, I suppose the Buddhist approach is, just do it, on the spot, rather than reliance on the great white hope that something just might happen, and therefore, we should push toward it. In that case you never see the end product; you just keep pushing all the time; this tends to make things very vague, in a sense, and, at the same time, very aggressive. You cannot experience what is going on. From that point of view, the Buddhist approach is not really based on hope. It’s based on just sit and do it on the spot. Perhaps this may be a very powerful improvement. I particularly think a person’s mind begins to take a turn more toward experience, rather than faith alone. I think this is the core of the matter in politics as well: you are supposed to just have hope, rather than living experience; then hope becomes just a nonexistent entity. But you are still supposed to push on aggressively, struggle toward it. The idea, I suppose, in the Western world or the world of democracy, is the notion of bringing the Kingdom of God to earth, or trying to create the ideal Jewish level, or whatever, which is really a poverty-stricken way of viewing it. I am sure the traditional doctrines did not possess this kind of approach, but this is the way we see it and this is what we have: man is sort of wicked and fallen from God’s grace, and he should do penance and try to build things up. This is the sort of wretched attitude which is a problem. As long as we condemn ourselves, no confidence can take place. People are bewildered and only rely on technicians or technocrats or, for that matter, on theologians or politicians. One feels he is just a layperson and doesn’t possess a specialized knowledge or profession and hasn’t studied how to do things—therefore he feels completely outside of the situation. This is one of the greatest problems I see in the Occidental world.

SR: How would Buddhism approach social reform, brotherhood of man?

SR: Do Buddhists have a tendency to be isolationists?

Rinpoche: I don’t think so. Particularly because the mahayana Buddhist’s concept is to relate to your surroundings and try to help each other. The Buddhist notion is to use everything available around you to further yourself and your fellow sentient beings. Buddhists may be less aggressive, and if somebody wants to come and fight, they may not fight. They might defeat their enemy, but the way of fighting is, not so much of a fistfight or street fight, but taking advantage of the whole situation.

SR: From a mahayanist point of view, do you think we might have a closer relationship with all peoples?

Rinpoche: I think so. Definitely. Not only people but animals included—all sentient beings. (Laughter)

SR: So there might not be as much nationalism?

Rinpoche: Well, there would be the same sense of dignity and celebration, obviously, but at the same time, it would not be nationalism. When we talk of nationalism, that is a sign of weakness. A person wants to fight just anyone who enters his territory, to defend himself. Therefore, you call yourself a so-and-so nationalist. Which as a sign, a symbol, becomes an expression of a sense of territory and patheticness.

SR: Thank you.