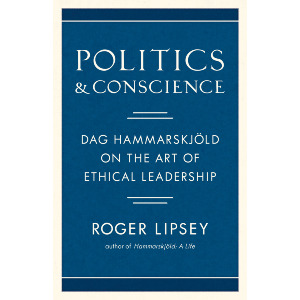

Politics and Conscience:

by Roger Lipsey

We have all become connoisseurs of leadership. Unintentionally, inescapably. This was already so in the pre-pandemic years of the Trump administration. However you assess those years, they were a civics lesson: checks and balances once taken for granted now visible, Constitutional requirements once respected now defied, the role of the US attorney general, and not least, the role of state governors, once minor now major. It has been a rumble. But our new citizen’s grasp of the design of government and the perils of misgovernment has changed several generations’ understanding and participation in political life. Hard earned, invaluable.

I published Politics and Conscience: Dag Hammarskjöld on the Art of Ethical Leadershipin February 2020, when we still didn’t firmly know that a deadly pandemic was poised to change nearly everything. I had certain ideas in mind for this compact handbook. Its broad aim was to bring political wisdom to the turmoil of American politics from a somewhat overlooked but truly grand source. Hammarskjöld was the second secretary-general of the United Nations (1953–1961), still honored as the foremost individual to have occupied that post. He could reach us, of this I was certain. His knowledge, attitudes, and language were as fresh as ever; no fading. He possessed practical, inspiring wisdom, grounded in his vast experience as the leading international statesman in a troubled, dangerous era. Further, he knew how to reflect his experience into the public space through press conferences, interventions at UN meetings, and addresses at universities and other institutions across the United States and worldwide. His posthumously published journal, Markings, added no end of dimension to what we already knew of him.

I think of him as the response, delayed by centuries, to the fiery brilliance of Machiavelli. Hammarskjöld’s is another fiery brilliance, no less realistic and passionate but dedicated to humanity—to the welfare and progress of all rather than the ascendancy of one dominant figure. Politics and Conscience is an exploration of modern leadership at its best, very much in Hammarskjöld’s spirit and often in his words. “It is difficult to hear the low voice of reason or see the clear little light of decency,” he wrote to a diplomatic friend, “but both endure and both remain perfectly safe guides.”

Politics and Conscience is very like Machiavelli’s classic guide, The Prince. Both are handbooks, both intended to be put to use. But they are opposite in color. With unforgettable lucidity, Machiavelli teaches his prince to attain and hold power, to dispose of enemies ruthlessly, to make war and preparation for war his central study. The prince “should not deviate from what is good,” he advises, “if that is possible; but he should know how to do evil, if that is necessary.” Elsewhere: “When he seizes a state the new ruler must determine all the injuries that he will need to inflict. He must inflict them once for all.” Machiavelli travels step by step over the terrain of coercive statecraft, of armed self-interest. The Prince shines with a dark light. It is never an error to read or reread it. Naturally, Hammarskjöld knew it thoroughly. “Even the much decried principles of Machiavelli can from time to time give us useful lessons,” he said in a cordial toast to the prime minister of Italy, “because they teach us to recognize and measure our illusions, and that is a discipline we can hardly neglect in the midst of the dangers of the atomic age.”

Hammarskjöld is Machiavelli’s equal in clarity and eloquence. Their aims differ. Throughout his years, more than eight, at the top of world affairs, he sought to give “peace and reason,” as he once put it, their greatest chance. He was as firm and resourceful in that direction as Machiavelli in urging his prince to secure and hold power. He was as adroit as Machiavelli’s prince, no less bold, but a servant of the good.

Hammarskjöld often said, “Fate is what we make it,” and our shared fate depends on our responses to the facts of our time. “No lasting success is possible,” he once said, “without the courage and the patience to face facts, any more than it is possible without the faith that mankind will reach its goal if we, every one in his own place, are willing to pay the price.” Goodness and pleasant values are not enough: “Even with the best of men half-hearted and timid measures will lead nowhere. The dynamic forces of history will overtake us unless we are willing to think in categories on a level with the problem.” And then, timing matters enormously. His experienced view offers a strong lesson for our moment and leaders. “I feel that when a danger does exist,” he said at a spring 1955 press conference, “we should act on the basis of that very fact that there is a danger and not give ourselves any leeway as to false speculations that the danger is far off in time; that is to say, whatever your guesses are concerning the time of certain possible threatening developments, you should act as if things might happen tomorrow.”

Hammarskjöld was a man of unshakeable integrity—and shrewd. He didn’t mind that word and quality, provided that it served just aims. Like Machiavelli, he had sufficient breadth of mind to survey the overall situation of humanity no less than to examine specifics. Politics and Conscience is a handbook of specific issues to care about, to reflect on and bring into one’s practice as a leader. For example, about the need for dialogue: “Dialogue is badly needed,” he once said, “but dialogue requires quite a few things: objectivity, a willingness to listen, and considerable restraint. Those are all human qualities. No one of them is very remarkable, but they are all called for.”

Hammarskjöld and Machiavelli differ also in their attention to the inner life of leaders. For Hammarskjöld, the identity of leaders—their internal sense of themselves and their values, their unseen but felt struggle to be truly of service—determines much that occurs for good or ill in the world at large. Machiavelli’s prince is something like a statue—powerful, rigid; his weight falls on his enemies. Hammarskjöld’s man or woman of good will and long political experience is mobile, principled, ready to immerse, to feel, to know: to lead wisely from within the human community, sharing hopes and sorrows.

Consider reading The Prince and Politics and Conscience side by side. The tensions and evolution of Western political experience will be brightly evident. They offer a choice that needs to be made again and again.

Share

$18.95 - Hardcover