| The following article is from the Winter, 2012 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Adapted from The History of the Karmapas

by Lama Kunsang; Lama Pemo, and Marie Aubele.

Most of us know that tulkus are recognized as reincarnations of specific masters, but we may not know the beginnings of the tulku system.

Here's the story, along with a bit of the fascinating history of the first recognized tulku and his magical dealings with the famed Kubilai Khan.

...when the disciples responsible for finding the tulku would come to inquire about the lama, he would already have written down the details birth.

H.H. 16th Gyalwa Karmapa and H.H. 14th Dalai Lama

Tulkus: The First Karmapa

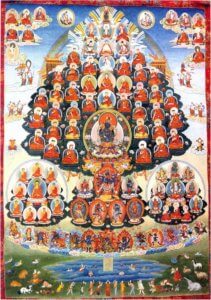

The first Karmapa, Düsum Khyenpa (1110-1193) made numerous predictions concerning his successors.

Before his death, he wrote a letter wherein he gave instructions for the discovery of his future incarnation, or tulku. Writing such a letter, which was sometimes transmitted orally to a trusted disciple, then became one of the methods for recognizing the Karmapas. Later it would frequently happen that even masters of other lineages called on the Karmapa to discover tulkus.

For example, the 15th Karmapa, Kyakyab Dorje, who lived at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, recognized around one thousand tulkus during his life.

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, a contemporary master, recounts the following:

Although he had unimpeded clairvoyance, the fifteenth Karmapa explained that he did not always have complete control over it. On the one hand, sometimes he would know when a lama was going to die and where he would be reborn without anyone having first requesting this information. Then, when the disciples responsible for finding the tulku would come to inquire about the lama, he would already have written down the details of the tulku's death and rebirth.

In other cases, he could only see the circumstances of rebirth when a special request was made and certain auspicious circumstances were created through any of a number of practices. And in a few cases, he couldn't see anything, even when people requested his help. He would try, but the crucial facts would be 'shrouded in mist.' This, he said, was a sign of some problem between the dead lama and his disciples. For instance, if there had been fighting and disharmony among the lama's following, the whereabouts of his next incarnation would be vague and shrouded in haze.

'The worst obstacle for clearly recognizing tulkus,' he explained, 'is disharmony between the guru and his disciples. In such cases, nothing can be done, and the circumstances of the next rebirth will remain unforeseeable.'

Three months before the passing of the first Karmapa, a number of unusual rainbows occurred, and mild earthquakes hit the area around Tsurphu, causing the population to say that the dakinis were showing themselves by playing the drum. The first day of the year of the Water Ox (1193), Düsum Khyenpa transmitted the Last Testament to his principal disciple, Drogon Rechen, who would become the main holder of the teachings of the Karma Kagyu lineage. He also entrusted his texts and reliquaries to him. Two days later, at dawn, Düsum Khyenpa gave a final teaching to his closest disciples. He then sat in a meditation posture, focused on the sky, and entered meditative absorption. At noon, after his breathing had stopped, he manifested the state of tukdam, the ultimate meditation at the moment of death.

The state of tukdam reveals the level of realization of the master. Although the vital functions no longer play their role, the body retains its suppleness, and the region of the heart stays warm; the head does not drop, and no typical odor of decomposition develops. On the contrary, it may happen that the followers smell a subtle perfume emanating from the body. Although the mind of the master has entered into the ultimate sphere of all phenomena, the dharmadhatu, it keeps a link with the body. This state of tukdam can last from many hours to many days.

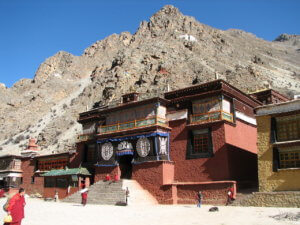

After the cremation rite for the first Karmapa, his followers discovered his heart and tongue (representing awakened mind and speech) intact in the middle of the ritual pyre, as well as fragments of bone on which appeared Buddhist symbols, particularly sacred syllables. The relics were collected and placed in a stupa in Tsurphu Monastery.

Dealing with Kubilai Khan: The Second Karmapa

The Second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi (1206-1282) was born in Kyil-le Tsakto, in eastern Tibet, in the Wood Rat year (1204), into a family descended from the famous Tibetan king, Trisong Detsen. His parents were yogins, and Karma Pakshi was their last-born child. Just before his conception, his mother dreamt of a sun composed of light emanating from her heart, with rays illuminating the entire world.

His parents, convinced that their son possessed rare spiritual qualities, entrusted him to Pomdrakpa, to whom the previous Karmapa had given the Last Testament shortly before his death.

Pomdrakpa very quickly realized that his young student was, in his own words, "blessed by the dakinis." This conviction had already been strengthened by a vision in which Düsum Khyenpa, the first Karmapa, as well as other Kagyu lineage lamas, surrounded the child's house.

When the child was eleven years old, Pomdrakpa officially recognized him as a tulku of the first Karmapa, ordained him as a novice, and gave him the title of Chokyi Lama, "Master of the Dharma." This period was a key moment in the history of the lineage, as it marked the beginning of the tulku recognition system. It was later applied, with some variation, by all the masters of other schools.

The Mongols had become the masters of the Sino-Tibetan borders when, in 1251, the grandson of the great Genghis Khan, Kublai (also spelled Kubla or Khubilai), then governor of the provinces of the west and greatly interested in the philosophy and wisdom of Buddhism, invited the Karmapa, now in his forties, to his residence. The lineage head's reputation had reached even his ears.

giving the Tibetan lineage head his freedom and assuring him that he could spread the Dharma everywhere without fear.

Karma Pakshi was aware of the great importance of the meeting for the future relationship between the two peoples. In 1254, despite the risks involved, the Karmapa accepted the invitation and was received a few months later by an important Mongol delegation that had advanced to meet him. It was customary to go out to meet important personalities as a sign of respect; the more prestigious the person, the further away they would be met. Thus, in 1255, the Karmapa was ceremoniously led to the Kubilai's residence.

Once at the court, Kubilai' gave the Karmapa his complete attention and showered him with gifts. The Karmapa's reputation as an accomplished master with extraordinary powers greatly impressed the Khan and his court, and he ardently hoped that his guest would display his qualities before the Mongol religious heads. The Karmapa agreed to satisfy Kubilai's request, and his prestige was further elevated. Enamored, the future emperor wished to keep this great master permanently near him, but Karma Pakshi, refusing to become involved in the intrigue plotted at the court, declined the offer, which gravely offended the Mongol chief.

They desperately tried many times to inflict the worst tortures on him: burning him at the stake, poisoning him, throwing him off a cliff.... Nothing worked.

His meditations on Mahakala and Avalokiteshvara strengthened Karma Pakshi's resolve to leave the Khan and move to the Minyak kingdom in the northeast of Tibet. The Karmapa's return journey was troubled by these events, and he sensed the imminent danger.

Kubilai Khan had not forgotten the "affront" he thought himself to have suffered some years earlier. Influenced by instigators in his court, he was convinced that Karma Pakshi had plotted against him. He therefore decided to have the Karmapa assassinated and sent troops in pursuit. The soldiers succeeded in arresting the Karmapa and quickly set themselves to carrying out Kubilai's orders. They desperately tried many times to inflict the worst tortures on him: burning him at the stake, poisoning him, throwing him off a cliff.... Nothing worked.

Finally, Kubilai understood that he was dealing with an exceptional master and begged forgiveness.

Once Kubilai was informed of these events, he decided to send Karma Pakshi into exile in the desert, hoping that he would eventually die of privation in this savage environment. However, not only did the Karmapa withstand the new ordeal, he even succeeded in drafting a number of religious texts. Finally, Kubilai understood that he was dealing with an exceptional master and begged forgiveness. Moreover, he offered him gold and asked him to stay at his court. Karma Pakshi refused the gold, but agreed to stay with Kubilai for some time and bestowed new teachings upon him to renew their bond.

In Marco Polo writings, he recounts Tibetan lamas capable of accomplishing miracles

When Karma Pakshi desired to return to Tibet, this time Kubilai acquiesced, giving the Tibetan lineage head his freedom and assuring him that he could spread the Dharma everywhere without fear. It was during this period that Marco Polo lived at the Mongol court of China. In his writings, he makes reference to Tibetan lamas capable of accomplishing miracles and recounts festivities in the great reception hall, where the Great Khan presided at a table floating many meters above the ground with goblets that mysteriously set themselves before the host and his companions.

Related Articles:

For more information: