| The following article is from the Spring, 1998 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

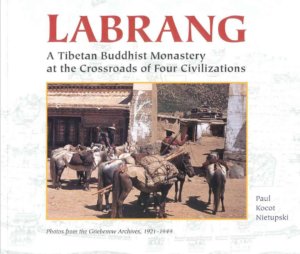

Labrang: A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery at the Crossroads of Four Civilizations

By Paul Kocat Nietupski, Photos from the Griebmow, Archives: 1921-1949.

Labrang stands out from the growing number of picture books on Tibet. Focusing on Labrang Monastery and its territories, this volume contains photographs taken over a twenty-five year period prior to the Chinese invasion that capture and preserve the life of this Tibetan monastery at its developmental peak. It includes narratives of people and events important in Labrang's early twentieth-century history and thus helps the reader enter into the life of one of the largest and most important centers of Tibetan culture.

This book is about the peoples and cultures that mingled at Labrang, but it is also about Blanche and Marion Griebenow, two young Christian missionaries, who against the advice of their families traveled to remote Tibet to spread the Christian message. They left the United States separately for what was then a region hostile to foreigners. They were married in Tibet and raised a family of four children. Their personal stories give a fascinating first-hand account of Labrang as it was.

Paul Nielupski, Ph.D is a scholar of Asian religions and cultures currently working in the Department of Religious Studies at John Carroll University in Cleveland, Ohio. His wide-ranging interests include the transmissions of Buddhism in medieval Asia and the interfacing of Asian religions and cultures.

Labrang was progressive with regard to religious and lay education.

Following is an excerpt from a chapter entitled Continuity and Change: Religious and Secular Education.

During the early decades of the twentieth century a number of unprecedented advances in education were attempted and realized at Labrang and in its territories. By no means did all Tibetan Buddhist monasteries have effective infrastructures or curricula for public education, but the evidence confirms that Labrang was progressive with regard to religious and lay education.

Labrang Monastery, with its libraries, its famous lineages of teachers and their disciples and its practice of public debate, exemplified Tibetan monastic education at its best. Although not all monks were good scholars or self-motivated and self-disciplined individuals (as in any educational institution), Labrang maintained rigorous courses of study.

The monastery was in effect a university divided into colleges, with different specialties and courses of study in each one, based on the classical Indian Buddhist model. The special fields were in all Buddhist sciences, the study and practice of Buddhist Sutras and tantras, and the entire range of associated meditations, medicine, arts and humanities. Most of these specialties were housed in their own buildings and facilities at Labrang.

The Labrang Monastery accommodated theories and techniques from all the Tibetan Buddhist lineages.

The Curriculum

The curriculum included fully developed courses, debates, and ritual practices. All courses functioned on a strict lunar calendrical system, observing all major Buddhist festivals and commemorations throughout the year in addition to special events that required religious recognition.

The specific content of the curriculum was broad-based, including memorization of and debate on major Buddhist sutras, the teachings of the Buddhist Middle Way (madhyamaka), epistemology (pramana), monasticism and ethics (viiiayd), categories of selves, persons, and things, and the tevels of consciousness (abhidharnm), the wisdom literature (prajnaparamita), the entire system of Buddhist tantras, astrology, medicine, and other topics. There were regular classes, examinations, and degrees awarded in these subjects.

[It was] designed to protect against the development of prejudiced interests in the monastic administration.

Though it had roots in the orthodox Gelukpa tradition of central Tibet, Labrang Monastery was not a strictly sectarian institution. In addition to the prominent central Tibetan Gelukpa systems, Labrang housed specialists in the older Tibetan Nyingma system and accommodated theories and techniques from all the Tibetan Buddhist lineages.

The abbotship rotated every three years, a procedure designed to protect against the development of prejudiced interests in the monastic administration. Though pluralistic in its academic approach, monastic education was not available to everyone throughout the extended community.

Young monks at Labrang Monastery

There were at least seven major religious festivals in the monastic calendar year during which the monastery and grounds were open to the public. Many thousands of Tibetans would come to Labrang for these festivals, camping on the banks of the river, prostrating themselves and praying in the hundreds of temples and shrines, viewing the ceremonial monastic dances, and participating in the secular ones. Travel or pilgrimage to sacred sites was an important part of Tibetan Buddhist religion.

The repertoire of religious practices at Labrang included a variety of local and borrowed beliefs and practices. At Labrang Monastery there were shamans and healers, Tibetan non-Buddhist Bon practitioners, propitiation of non-Buddhist deities, and beliefs in a wide range of myths.

At the core of this array stood a Tibetanized model of an Indian Buddhist monastery. Thus, though the most esotericrituals were reserved for monastic experts, some of the highlights were shown to the public to indicate the presence of the divine in their midst. These public rituals were considered by lay people to bestow good luck; by seeing the deities, pilgrims were in turn seen by and thus blessed by them.

Development of the monastic schools did not cease in the twentieth century. In 1939, the Fifth Jamyang Shaypa established the Upper Tantric College (Gyuto) at Labrang, after the Lhasa model.

The Fifth Jamyang Shaypa also attempted to modernize the curriculum at Labrang by including secular studies imported from China. His incorporation of new ideas was an attempt to upgrade Labrang's curricula and practices.

Additionally, the Fifth Jamyang Shaypa is known for his efforts to preserve Tibet's literary heritage by his continuing search for, collection and preservation of rare Tibetan Buddhist manuscripts in the large library at Labrang. His achievements were substantial in terms of his enthusiastic support of both the monastic curricula and lay education.

Surviving and Thriving in the Early Twentieth Century

The monastery had an elaborate system for the dissemination of political and religious rules to the tribal groups and the peoples in the Labrang district, and to monasteries founded in faraway places under the auspices of Labrang. This system was obviously disrupted at times by warfare and chaos, yet Labrang Monastery developed into a major functioning educational institution rich in artistic treasures. It is indeed surprising that it survived almost unscathed during the turbulent years of the early twentieth century.

In the 1930's and 1940's Labrang not only maintained monastic education, but also pursued initiatives in public schooling.

After the 1927 war period, Apa Alo and Jamyang Shaypa introduced a new secular school system at Labrang to promote unity among the different ethnic groups in Amdo. They started schools for the ethnic chiefs and the local Chinese officials in which the participants would study Tibetan and Chinese languages, cultures, and histories.

Labrang, at least in the minds of the monastic and secular elite, was not a provincial institution without aspirations for development.

One of the goals in the push to develop educational systems was to replace the use of the Chinese language with Tibetan in the local schools. Though the times were chaotic, there was a commitment to disseminating religious and secular information to the public, even though success was intermittent.

It was this attitude that played a role in securing permission for the Griebenows to reside at Labrang. In this environment the Griebenows opened elementary literacy classes, which represented possible opportunities for access to Western information and technologies. Labrang, at least in the minds of the monastic and secular elite, was not a provincial institution without aspirations for development.

One of the academic innovators and an ally of the Tibetans was a Chinese, Xuan Xiafu. Xuan was active in promoting education in Labrang and Amdo, and was an especially loyal ally of the AIos. He was an early Nationalist Party member who later became a member of the Chinese Communist Party; in the late 1920s he also worked for Feng Yuxiang.

In the late 1920s Xuan Xiafu used his influence to get Apa Alo membership first in Nationalist Party's Youth Corp, and then in the Lanzhou branch of the Party Committee. The Nationalist Youth Corp, members of which were all in their early twenties, actively promoted unity, national pride and political reform. With the Hui occupying Labrang, this movement was very attractive to Apa Alo.

At Labrang, unity and national pride meant something different than it did in China; it meant pride in the identity of Labrang as a center of Tibetan culture. The Youth Corp branch at Labrang promoted education, including Tibetan folk music and dance. The branch published a regular bulletin in which Apa Alo once introduced a proposal for Tibetan nomad grasslands region crossing the boundaries of the Chinese provinces into which it had been divided Gansu, Qinghai, and Sichuan. He argued that the Tibetan grasslands already represented a real political unit and deserved official recognition.

Schooling was open to all, young and old, male and female, and of any religious affiliation.

In 1928 two new schools were established in Golok territories, and the area's first girls' school was opened in 1940. There were only about twenty students at first, and never a large number, but enrollment gradually increased with several Tibetan, Chinese and Hui students.

Schooling was open to all, young and old, male and female, and of any religious affiliation.

The accounts of the Tibetan educational initiatives sound nearly too good to be true, and there is no doubt that they were historically recent, prototype-style programs. The interesting point is, however, that they did happen, they were innovative, and they reveal a genuine interest in educational development on the part of the ruling elite at Labrang.