| The following article is from the Winter, 2012 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

A Tibetan Non-dual Exercise

Mahamudra meditation techniques can help us break though directly to the nature of mind. This exercise is one of many step-by-step techniques offered in Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche's brilliant book, Pointing Out the Dharmakaya.

Mahamudra meditation techniques can help us break though directly to the nature of mind. This exercise is one of many step-by-step techniques offered in Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche's brilliant book, Pointing Out the Dharmakaya.

This technique begins with looking at an object of visual perception, such as a pillar, a vase, a wall, a mountain, and so on. It could be almost anything. It could be big, it could be small, it doesn't matter. Simply direct your gaze to that chosen object of visual perception and look at it directly.

At this point, we need to make a distinction between this use of an object of visual perception and the use of an object of visual perception in the shamatha techniques. In the techniques of shamatha or tranquility meditation, you direct your mind to a bare visual perception, for example, of a pebble or a small piece of wood. In that case, what you are doing is actually concentrating your mind on that visual perception; you try to hold your mind to that object. Here we're using the visual form in a different way. We're trying to use the experience of visual perception as an opportunity to discover or reveal the mind's nature, to see the emptiness or insubstantiality that is inseparable from the vividness of the perceptual experience. So what we are really looking at here is not the object but the nature or essence of the experience of the object, which is the unity of emptiness and lucidity.

It may be helpful when you are meditating on external appearances in particular, to allow the focus of your eyes, the physical focus of your organ of vision, to relax. Without allowing your eyes to focus on any one thing or another, allow your vision to relax to the point where you do not see any given thing particularly clearly. This will cause a slight reduction of the vividness or in- tensity of visual appearances and can help generate an experience of the nonduality of appearances and mind. The particular point here is to look in a way that is relaxed so that your vision is somewhat diffused and not focused on any one thing. By allowing your vision to be unfocused you will not see the details of the forms that are present in your line of vision. The reason why this is helpful is that it is by seeing details, through focusing on a specific thing physically, that we promote or sustain our fixation on the apparent separateness of visual perception.

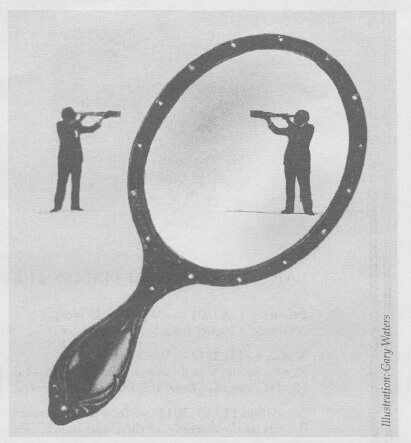

As you apply this technique, you are not really looking at the object. You are looking at that which experiences the object.

In this technique, look with your eyes in a way that is very relaxed so that, not seeing the details of any of the things in your line of vision, your mind will start to relax and you will experience an absence of separation between the perceived external objects and the perceiving or experiencing cognition. Whereas we normally think that externally perceived objects and the perceiving cognition are inherently separate, that the one is out there and the other is in here, nevertheless, when you relax your vision in this way and simply look without concepts at appearances, then in your experience at that time, there will be no distinction between the apprehended objects and the apprehending cognition. There are still appearances, you are still physically seeing things, but there is no fixated apprehending of them.

So look directly at the object, but without examining it or particularly attending to its characteristics, and don't be too outwardly focused on the object. You don't need to stare at it wide- eyed. Look at your experience of the object and simply see the insubstantiality, the emptiness of the experience.

So look directly at the object, but without examining it or particularly attending to its characteristics, and don't be too outwardly focused on the object. You don't need to stare at it wide- eyed. Look at your experience of the object and simply see the insubstantiality, the emptiness of the experience.

Having directed your attention to the experience of the object of visual perception, then relax slightly, and then look again. By alternating relaxation and attention to the experience of the object, you can continually examine that experience, by looking at it directly. In the same way, you can apply this technique to the other sense consciousnesses, to the experience of sound, of smell, of taste, and of tactile sensations. When you do this, then you are looking at the nature of the experience of the object in each case, rather than at the characteristics of the objects themselves. You're looking to see if there is any substantiality whatsoever in the consciousness that is this experience of the appearance of the visual form or the sound or whatever it may be.

Among other things, you can look to see what are the differences, if any, between different consciousnesses of different objects. For example, is the consciousness that is generated when you see something yellow different from the consciousness that is generated when you see something red? Or, is the eye consciousness generated when you see a form different from the ear consciousness that is generated when you hear a sound? Of course, they are different in the coarse sense that one is an eye consciousness and the other is an ear consciousness. But is the nature of the mind or consciousness that experiences these two types of objects fundamentally different?

As you apply this technique, you are not really looking at the object. You are looking at that which experiences the object. You can also look to see where that consciousness arises. Does it come from anywhere? Does it abide anywhere? Does it go anywhere? If you come to the conclusion that it arises in such and such a way and goes somewhere else or disappears in such and such a way, that is probably conceptual. You have to look very directly. It can't be a matter of speculation or reasoning. This is very different from analyzing sense perception and thinking that this consciousness must arise from these causes and conditions and must dissolve in such and such a way. It's a matter of looking directly at the consciousness that experiences.

When you're looking at the consciousnesses that experience these external appearances, then you're experiencing the essential emptiness of that consciousness. You do this by looking at the consciousness to see if it has any substantiality. For example, if I'm taking a vase as the objective support for the technique, then what is happening is that I am generating an eye consciousness of the vase. With regard to the eye consciousness that is generated in bringing together my eyes and the vase I see: where exactly is this consciousness generated? Does this consciousness arise in the vase? Does the consciousness arise in my eyes? Does it arise somewhere in between them? If it arises in between them, does it actually fill the distance between the vase and my eyes? Or is it less substantial than this? Is it insubstantial? These are the kinds of things to be looked at.