| The following article is from the Spring, 1950 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

The Essence of Dzogchen in the Native Bön Tradition of Tibet

Foreword by H.H. the Dalai Lama

This book will be of great help to readers wishing to find a clear explanation of the Bön tradition, especially with regard to its presentation of the teachings of Dzogchen. - H.H. the Dalai Lama

Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche and the History of Bön

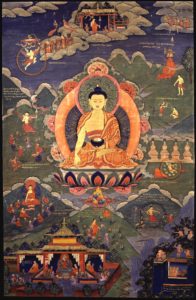

Bön is the ancient autochthonous preBuddhist religious tradition of Tibet, still practiced today by many Tibetans in Tibet and in India. The founder of the Bön religion in the human world is Lord Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche.

Tonpa Shenrab descended from the heavenly realms and manifested at the foot of Mount Meruwithtwoof his closest disciples, Malo and Yulo. Then he took birth as a prince, the son of King Gyal Tokar and Queen Zanga Ringum, in a luminous garden full of marvellous flowers in a palace south of Mount Yungdrung Gutseg, at dawn on the eighth day of the first, month of the first wood male mouse year (1857 B.C.). He married while young and had children. At the age of thirty-one he renounced his worldly life and started to practice austerity and teach the Bön doctrine. Throughout his life his efforts to propagate the Bön teachings were obstructed by the demon Khyabpa Lagring, who fought to destroy Shenrab's work; eventually he was converted and became Shenrab's disciple. Once, Khyabpa stole Shenrab's horses and Shenrab pursued him through Zhang Zhung into southern Tibet. Shenrab entered Tibet by crossing Mount Kongpo.

This was Shenrab's only visit to Tibet. At that time the Tibetans practiced ritual sacrifices. Shenrab quelled the local demons and imparted instructions on the performance of rituals using offering cakes in the shapes of the sacrificial animals that led to the Tibetans abandoning animal sacrifices. On the whole, he found the land unprepared to receive the five Ways 'of the fruit' of the higher Bön teachings, so he taught the four Ways 'of cause.' In these practices the emphasis is on reinforcing relationships with the guardian spirits and the natural environment, exorcising demons, and eliminating negativities. He also taught practices of purification by fumigation and lustral sprinkling and introduced prayer flags as a way of reinforcing fortune and positive energy. Before leaving Tibet, he prophesied that all his teachings would flourish in Tibet when the time was ripe. Tonpa Shenrab passed away at the age of eighty-two.

Mythological Origin and History of the Bön Religion

According to Bön mythological literature, there were three 'cycles of dissemination' of the Bön doctrine, in three dimensions: the upper dimension of the gods or Devas (lha), the middle dimension of human beings (mi), and the lower dimension of the Nagas (klu).

In the dimension of the Devas, Shenrab built a temple called the 'Indestructible Peak that is the Castle of the Lha' and opened the mandala of the 'All-Victorious Ones of Space'; he established the Sutra teachings and appointed a successor, Dampa Togkar.

In the dimension of the Nagas, he built a temple called the 'Continent of the Hundred Thousand Gesars that is the Castle of the Nagas' and opened the mandala of the Pure Lotus Mother. He established the Prajnaparamita Sutra teachings and gave instructions on the nature of the mind.

In the human dimension, Shenrab sent emanations to three continents for the welfare of sentient beings. In this world, he originally expounded his teachings in the land of Olmo Lungring, situated to the west of Tibet and part of a larger country called Tazig, identified by some modern scholars as Persia or Tazikhistan. 'Ol' symbolizes the unborn, 'mo' the undiminishing, 'lung' the prophetic words, and 'ring' the everlasting compassion of Tonpa Shenrab.

Further History of Bön

With the spread of Buddhism in Tibet and after the founding of the first Buddhist monastery at Samye in 779 during the reign of King Trisong Detsen, Bön underwent a decline in Tibet. Although at first King Trisong Detsen was reluctant to eliminate all Bön practices and even sponsored the translation of Bön texts, he later instigated a harsh repression of Bön. The great eighth century Bön master and sage Dranpa Namkha, father of the Lotus born Guru Padmasambhava, founder of the Nyingmapa (rNying ma pa) Buddhist tradition and the master who spread the Tantric and Dzogchen teachings in Tibet, embraced the new religion in public but maintained his Bön practice and allegiance in private in order secretly to preserve Bön. He asked the king Why do you make a distinction between bön and chos? (The word bön' for the Bönpas and chos' for the Buddhists both mean dharma', or truth'), since he held that in essence they were the same. Vairocana, the Buddhist scholar and disciple of Padmasambhava, and many other translators of Indian and Oddiyana Buddhist texts participated in the translation of Bön texts from the language of Drusha To be saved from destruction, many of the Bön texts had to be hidden as termas so that they could be rediscovered later in more propitious times.

In the ninth and tenth centuries, Bön suffered further persecutions and attempts to eradicate it. Followers of Bön, however, were able to preserve the scriptures until the eleventh century during which time there was a Bön revival. This was precipitated by the rediscovery of several important texts by Shenchen Luga, a descendant of the great master Tonpa Shenrab himself.

Shenchen Luga had many followers, some of whom founded the first Bön monasteries in Tibet. In 1405, the great Bön master Nyamed Sherab Gyaltsen founded Menri monastery. Menri and Yundgrung Ling monastery became the most important of the Bön monasteries.

THE Bön DOCTRINE

Different Presentations of the Bön Teachings

The Bön teachings imparted by Tonpa Shenrab are presented in various ways and with different classifications in the three written accounts of Tonpa Shenrab's life. Shenrab is said to have expounded Bön in three successive cycles of teachings: first he expounded the Nine Ways (or successive stages of practice) of Bön'; then he taught the Four Bön Portals and the Fifth, the Treasury'; finally he revealed the Outer, Inner, and Secret Precepts.'

The First Cycle: The Nine Ways

There are three different ways of classifying the Nine Ways of Everlasting Bön: the Southern, Northern, and Central Treasures. These are systems of teachings that were hidden during early persecutions of Bön to be later rediscovered as termas. The termas rediscovered in Brig mtshams mtha' dkar in south Tibet and in sPa gro in Bhutan constitute the Southern Treasures; those rediscovered in Zang zang Lha dag and in Dwang ra khyung rdzong in north Tibet constitute the Northern Treasures; those rediscovered at bSam yas and in Yer pa'i brag in central Tibet constitute the Central Treasures.

In the Southern Treasures, the Nine Ways are subdivided into the lower Four Ways of Cause', which contain the myths, legends, rituals and practices concerned mainly with working with energy in terms of magic for healing and prosperity, and the higher Five Ways of the Fruit', the purpose of which is to liberate the practitioner from the cycle of samsaric transmigration.

The Nine Ways of the Northern Treasures are not widely known. In the Zang zang ma system, they are divided in three groups: external, internal, and secret.

The Nine Ways of the Central Treasures are very similar to the Nine Ways found in Nyingmapa Buddhism. In fact, they are cycles of Gyagarma teachings that were introduced into Tibet from India and were translated by the great scholar Vairocana, who worked as translator in both the Bön and Buddhist spiritual traditions.

The Second Cycle: The Four Portals and the One Treasury

The second cycle of Bön expounded by Shenrab is divided into five parts. The First Portal deals with esoteric trie practices and spells. The cond Portal consists of various rituals (magical, prognosticatory, and divinitory, etc.) for purification. The Third relates rules for monastic discipline and lay people, with philosophical explanation, and the Fourth instructs on psycho-spiritual exercises such as Dzogchen meditation. The fifth teaching is called the One Treasury and comprises the essential aspects of all four portals.

The Final Cycle: Outer, Inner and Secret Precepts

The final teachings expounded by Tonpa Shenrab consist in the three cycles of Outer, Inner, and Secret Precepts.

The outer cycle is the path of renunciation (spong lam), the Sutra teachings. The inner cycle is the path of transformation (sgyur lam), the Tantric teachings, which use mantras. The secret cycle is the path of self-liberation (grol lam), the Dzogchen teachings. This division into Sutra, Tantra, and Dzogchen (mdo sngags sems gsum) is also found in Tibetan Buddhism.

Sutra, Tantra, and Dzogchen

According to Bön, the five passions: ignorance, attachment, anger, jealousy, and pride, are the principal cause of all the problems of this life and of transmigration in samsara. They are also called the five poisons because they kill people. It is these passions that we must overcome through practice. According to the Sutra view, it takes many lifetimes to purify the passions and achieve enlightenment, whereas according to the Tantric and the Dzogchen views the practitioner can attain enlightenment in this very lifetime.

Different religions and spiritual traditions have devised various ways of purifying the passions and attaining realization. In Yungdrung Bon, these are the method of renunciation, the method of transformation, and the method of self-liberation.

For dealing with the passions, we can use the example of a poisonous plant. According to the Sutra interpretation, the plant must be destroyed, because there is no other way to resolve the problem of its poison. The Sutra practitioner renounces all the passions.

According to the Tantric system, the Tantric adept should take the poisonous plant and mix it with another plant in order to form an antidote: he does not reject the passions but tries to transform them into aids for practice. The Tantric adept is like a doctor who transforms the poisonous plants into medicine.

The peacock, on the other hand, eats the poisonous plant because he has the capacity to use the energy contained in the poison to make himself more beautiful; that is, he frees the poisonous property of the plant into energy for growth. This is the Dzogchen method of effortlessly liberating passions directly as they arise.