Irene messaged me a few months after her son Oliver had died of SIDS, another episode in our ongoing conversation from one continent to the other. Looking for you today. I hope you don’t mind.

Oh! Are you okay love?

No, but I’m getting used to it now and don’t expect it to be any different for the next while. The biggest thing for me is the anger at people who are being jerks. Even those close to me. I can’t shake it off. It’s exhausting. How are you?

I still feel that way sometimes. It’s softer now than it used to be, but when I talk about it (rare these days) it triggers everything all over again. When I remember how someone called Liam a “gynecological mishap,” it’s like an electrical current of anger through my body just as vivid as a decade ago. Back then I was in shock, and I didn’t have the energy to stand up for myself. But I saw it for what it was, somehow. I knew the problem wasn’t me, but them. It was a wellspring of self-protection, but it comes with some pretty painful revelations and complicated feelings. Keep talking to me. When we connect with each other, we take the power away from the jerks. That’s how you realize everything is universal. The loneliness, the dismissals. You can talk back or walk away, but either way, quietly rearrange your circle to keep allies close to you.

I feel like a bullshit magnet.

Yeah. Your reaction—naming and pointing at the jerks, even if it’s just in your head—that’s your dragons stepping up for you. That’s your wellspring.

THANK YOU.

Doesn’t matter if you give your dragons an explicit voice or not. They will stand in between the soft parts of you and the bullshit. They’ll fade when you don’t need them anymore, but they’ll never go away. They’ll always be watching. They’ll be proud when you don’t need them and instantly onside when you do.

. . . . . . . .

What is it about the death of a baby that either brings all the bullshit out of the woodwork or inspires otherwise decent people to say bullshitty things? It’s a phenomenon.

I have a vested interest and will therefore snap her out of this, they think. Then out it comes. Paraphrased: Look at the Millers, the family with the daughter who lives in the bubble for her immune system. Or the Robinsons with the alcoholic and the foreclosure. You’re not the only one in the world who hurts, you know. Stop dwelling. Think of all the people around you who need you to be uplifting. Be like so-and-so with the Down syndrome boy. She’s always so positive.

My only regret, in hindsight, is that I’d sit there with my mouth hanging open, flies buzzing in and out like Homer Simpson at the control panel of a nuclear power plant. It was too much to unpack. I went outside myself, observing from some other place, as detached as I could be. It was bizarre, but thank god, I knew it at the time. With my mouth hanging open, I’d think What that person just said is sociopathically awful.

The corrective/punitive stuff would come from people beset with forcibly submerged pain on the inside, a tidy spit-polish on the outside, and an aggressive commitment to keeping it that way. I was a threat to be neutralized. Turning me proper—sweeping the unmentionable under rugs, like Kleenex draped over a garbage heap (Nothing to see here, folks)—would have been proof of everything being in its place, with no place for me as I was.

If you’re going to be a Coper—not one of those Non-Copers—you should just forget it. So-and-so did. She doesn’t even remember. She never complains, because she’s great. She’s optimistic! You should be like her. You should be strong enough to pretend it never happened.

Homer Simpson . . . buzzing flies.

I knew what health was. And I knew I had it. I was doing well, given what we’d been through. I wasn’t curled up in a ball, crying all day (had I been, that would have been fine). I wasn’t talking nonstop about what happened (had I been, that would have been fine). I rolled around on the floor with my two-year-old. I grilled cheese and chained daisies. I cried sometimes. Then to bed and up again in the morning for the NICU commute. I’d push those swinging double doors open and step across the threshold to scrub in like Jesse James.

Sometimes, when someone would ask me how I was doing, I’d answer vulnerably. Truthfully. I’d say I’m upset. I’m scared. Slowly clotting blood is leaps and bounds better than infection, and I was willing to bleed. Made to live through it again I would choose to be, do, say, and feel the same way with no hesitation. For two months I pumped and cuddled, loving both of those boys regardless of what their outcomes might be. I forced myself to stare unblinking at the horror until I could see the beauty underneath all the wires and tubes because dammit, if one or both of them were to die, I wanted to know as much as I could of their hearts, their eyes, their soft skin, their grunts. Not only their machines and their misfortune.

My pain has always been a clean pain. People with garbage heaps swept under rugs can’t say the same. That has nothing to do with me, nothing to do with you.

On the flip side of the forcible bootstraps barbershop chorus is the silent majority:

“What a crummy spring we’re having . . . too much rain, eh?” he mumbled as he stared at his shoes. I hadn’t seen him since Liam died. I knew he knew. He knew I knew he knew. He stood in front of a wrinkled, gray, twenty-foot trunk spitting peanuts against his forehead with a shwuck! schwuck! schwuck! as he shrugged: Elephant? What elephant?

I’m being considerate, the silent majority congratulates itself.

I’d always walk away thinking less of you, silent majority. You were smaller than I had thought you were. You were afraid of death cooties. It’s years later and I still think you’re a chickenshit. You, just as much as the grief-shaming barbershop chorus.

. . . . . . . .

For two months I pumped and cuddled, loving both of those boys regardless of what their outcomes might be.

Years later, I’m in a café writing this chapter with my shoulders all jammed up against my ears. The outrage—the self-protective mechanism—kicks in, and I wonder if I’ll ever be able to let it go.

In my head:

Good for you for seeing toxic people for what they are.

That’s harsh. Tolerance for compassionless people is the master class of compassion.

Screw tolerance.

You gonna be this prickly forever?

At least I’m not prickly on the outside. Most of them don’t know what I really think.

Doesn’t matter if they know or not. You’re still carrying it around.

We’re nuts, huh? We’re all nuts.

Here’s a new outlook on ineptitude of all kinds. I’ll share it with you because someone shared it with me.

You’re at the dinner table, on the street, bumping into people who either know exactly what to say (the wrong thing), or who say nothing. You’re standing there with your mouth hanging open. You feel abandoned, shamed, isolated. You might feel like nobody cares. You might feel damn near abused by thoughtlessness.

Here’s your mantra: Jane is doing the best she can.

This abhorrent scene represents the very best she can do. That’s what all of us are doing at any given moment, given our demons and distractions. Our contextual best. And this particular criticism, dismissal, or peanut-gallery correction has nothing to do with you. Absolutely nothing. You need not respond to it, and you need not take it on as something to consider.

So close your mouth. Flies are gross. Flies land on poop. Nod, mutter something, get away. Find some fresh air. Spend your life with people who don’t stare at their shoes, and who aren’t afraid of the dark.

If you can’t get away, embark on a lifelong practice of expecting as little as possible—nothing, if possible—from certain people. You know who they are. What sounds like pessimism is peace. As soon as you detach from the expectation that Jane might someday change her behavior, you’re following a sliver of the Buddhist way, the right way, and you don’t need to know anything about the Rinpoche to do it.

Einstein said the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. It’s similarly fruitless to attach meaning to someone else’s pattern and to let yourself be repeatedly hurt by it. It’s not worth the energy to even inwardly grumble about it. So don’t. Jane’s pattern will repeat itself again and again and instead of feeling like your face is going to explode, again and again, stand there and say to yourself: What we have here is Jane being Jane. This is her way of . . .

Who knows? Who cares? She is unlikely to ever change. Neither will Dick.

. . . . . . . .

I wrote. I wrote so much. I hadn’t yet found anyone else who was bereaved in this way and needed the exercise of trying to find words for what was inexpressible. It was satisfying in the same way it’s satisfying to pressure wash something filthy. You animate the inanimate with attention. You hear it say Aaah. A surface feels pleasure at its dirt being noticed and addressed, running in rivulets down the road. Even though it knows the dirt—the pain—will collect again. The practice of exposure to light and air is worth it, even for an afternoon.

A farmer friend of mine watched my doves taking a bath in a tourtiere plate. They shook and dipped and shook gloriously, thrilled. “Giving an animal what it needs to clean itself is the most wonderful and basic kind of caring,” she said, smiling. “Even for the little ones.”

To write—to make any art and be generative, either in solitude or with company—is animal husbandry for dragons. It calms them.

The day after the twins were born, a distant relative came to the hospital with a gift. The drugs were still wearing off. I was unable to move, but I was conscious.

“Here,” she said. “This is for you.”

I reached out to take it with shaky hands. It was an empty, lined book.

“You can write in here,” she continued, explaining. “Since you can’t write about this anywhere else. I mean, nobody would want to read it. I mean, you wouldn’t want anyone to think. . . anyway. This is so you can keep all this to yourself. Obviously.”

Remembering that moment years later, I transport myself back to that hospital room. But not as the Kate with the freshly stapled incision. I am today’s Kate, the ghost of her future. People will say “there’s no right way to grieve,” but there is, I whisper to her. Or at least there’s a wrong way to show up, and that’s what you see in front of you. Carry on.

The Kate of 2007 hears the Kate of 2017.

“Right, I’ll do that,” she lies to the roomful of people, who watch approvingly. She is carrying on. Good girl.

I filled the notebook and what felt like a hundred more. I look at them sometimes. I flip to a page and see myself hanging on to cliffs with my fingertips, near hysterical in how alone I felt. But I didn’t keep it to myself. I shared everything as it unfolded because that’s what was right for me. I founded a community for us, a place safe from mixed company where talking about feeling suffocated helped us all to breathe. I spoke at memorial walks. I made my own light and air. In all kinds of ways I allowed my pain to clean itself. I cared for it. And I wasn’t alone at all.

FIELD NOTES

80-Page Steno Book

Ruled Paper / Durable Materials

Double-O Wiring / 6 x 9

February 2, 2016

In a performance hall watching this brilliant, accomplished woman talk about innovation. Feeling quite a bit like a caveman, from the woods by a Nova Scotian creek to shining glass in downtown Vancouver.

What is the takeaway? In business they call it “disruption,” and they—the smart ones, anyway—say disruption is integral to positive change. Nothing happens without a shock. She is talking about market strategy and team dynamics and I am listening, mostly, but in my mind, everything she says points to Liam. Not to reduce him to a prop for personal growth. But I am left here without him. There is no bigger disruption. The shock still unfolds, though more gently than it once did. For the rest of my life I will grapple with his absence. Grappling is growth.

I can’t love him by wiping his nose. I can’t open his bedroom door, see he’s all gummed up in his blankets, and creep into the dark to untwist him, clammy limb by limb, for a fresh tuck. I can’t shampoo his hair or turn his socks right side out. I can’t stand it that he’s not here. But would I have rather not known him at all? The mass of this pain is still inside me. I wish I didn’t have to carry it. But I’d be his mother a thousand times over. I appreciate his imprint on who I am more than I resent the pain of witnessing his death.

Covering a lecture for a client, I flipped to an empty page to doodle LIAM in block letters, with one star that looked like the hand-cut cookie of a three-year-old. LIAM. It was almost entirely absentminded, his name existing for me somewhere on the spectrum between sacred core and curiosity. One moment I’d been riffing on what I was hearing about experience design and corporate social channels and the next, my thoughts had drifted to him. I was almost a decade beyond him, yet I was adding polka dots to the M before I realized what I was doing: noting the disruption that made me.

Disruption. When the twins were born three months early, I didn’t have access to a particular faith or philosophical array, but I didn’t feel a lack of one either. A hospital chaplain knocked repeatedly on the door, leaving notes about being available. I’ll come back tomorrow at 3:00, he’d write, and the next day at 3:00 I’d hide in the bathroom until his knocking stopped. But I worried, a little, that all I had was writing. Would it be enough? Was it the right thing, or was it “dwelling”?

Disruption. Suddenly, you’re in over your head. You are flailing, panicking. Your faith or philosophy is not the life jacket you’d thought it would be. It is a Victorian ball gown with hoops and layers, forty pounds of ruffles and bustle and a corset designed for admirers, a shallow breath, and a straight back. It identifies you, as long as you’re on solid ground. It is your swank and swagger. But as soon as you hit the water, it wraps around your legs and lungs with the buoyancy of cinder blocks.

To be shaken, uncertain, and searching for answers is to be naked. No god has betrayed you, no prayer had gone unheard. No theory was catastrophized into an ultimate test. If you’re going to be dropped into water over your head, you may as well be in your skin. Keep the ball gown. It’s a part of you too. But know when to let out a seam. Don’t buy into everything they tell you that you should be and shouldn’t. Make it as easy as possible to find the rhythm of your dog paddle.

. . . . . . . .

Don’t Complain. You are not so special. Other people have it worse than you. You need to get over it. Don’t Complain.

Good Christians don’t. I expect the good Muslims and good Jews and good Hindus and all the other good devotees aren’t supposed to either, because to complain is to take issue with the grand master’s plan. Swishy proper types don’t. If you want everyone who meets you to marvel at your perfect manicure and perfect disregard for all emotions in the UNDIGNIFIED category, to complain is to invite the side eye of other swishy propers. The nouveau Bohemian types aren’t supposed to either. See also: The Secret and viral Facebook memes and airport self-help books about how Positivity! rewires brain synapses to Manifest! Good! Things!

But—

But—

But—

If nobody ever complained, nothing would ever happen. No change, no growth. Like that movie about the town stuck with black-and-white pin curls and pressed slacks, every shirt tucked in and every button buttoned, but with no fistfights and no back seat hand jobs, no midnight ice cream, no musty basements, no French kisses, no gay uncles, no cotton candy cavities, no thrilling risks, no vagina-as-flower art, no smashing glass, no rose cream macarons, no keggers, no stray farts or nipples, no Thanksgiving politics, no caramel wrappers found stuffed between the couch cushions. No complaints. No one to say Why can’t I (scream when I need to / say what I mean / be who I am)?

We are lusty and outrageous creatures. Our lust and our outrage is the furnace of our aliveness. Complain, dammit. Incorporate this new heat. Your baby died. Complain, darling, and weep and sob or talk about it to everyone or only yourself. Whatever is best for you. But complain. Complain until the heat of it brings you into your color. Gray and untouched is a half-life. The next time your peanut gallery winds up, say it out loud: Gray is the only true nothingness. Then walk away. Or imagine walking away.

. . . . . . . .

Don’t buy into everything they tell you that you should be and shouldn’t. Make it as easy as possible to find the rhythm of your dog paddle.

My mom, cooped up with a toddler and an infant, went to her first quilting bee and found art, meditation, and friendship. I’ve grown up surrounded by straight pins and fat quarters, bundles of fabric from floor to ceiling, baskets of ribbons and hoops, the hum of her machine, and a house full of women of all ages chatting and laughing and sewing with hot pots of tea and fancy cakes. They were all soft, to me, like my mother. Some were wrinkled and plain and beaming, others wore bright lipstick and hand-knit socks and smelled like flowers and lemon squares. They all were delighted and occupied, laps heaped full. They knew my name and asked with great interest how school was going, where I’d go to university. They’d pass around stacks of half-finished piecework to marvel at each other’s tiny stitches and rare cottons, their voices blending into a chirpy, contented murmur downstairs, their busy hands warming our house.

One day not long after our release from the NICU, with Evan at daycare having a Big Kid Day, I wandered the bins of the Bridgewater Frenchy’s—a chain of thrift shops that has punctuated the Maritime experience since before I can remember—with a sleeping, perhaps six-pound Ben wrapped up in the mei tai. I was pulling little long johns from the TODDLERS bin when I sensed someone walking my way. It was Polly, one of my mother’s first mentors and closest quilting friends. She has written books and had exhibitions. It was Polly who taught my mother how to sew.

“Oh! Hi,” I said, dropping the clothes in my hands and stepping toward her for a hug. She stopped in front of me and took me by the shoulders.

“Oh god, Kate, I am so sorry,” she said. “I heard what happened with Liam, and I am so upset for you. It’s awful, and I am so sorry. I just can’t believe it. How are you doing, Kate? Tell me, how are you?”

Polly, you should understand, isn’t one of the particularly flowery ones. She’s witty and sharp. She doesn’t stand for any fluff, if that makes sense. She’s passionately opinionated and direct, so when she said “I’m sorry,” she didn’t say it the way most people do, drifting-off. She said it how it’s supposed to be said. With fervor and agitation.

I can’t remember how I responded. I only remember she didn’t look away. She was angry for me. She felt it was wrong, backward, and unfair for a baby to die, and she wanted me to know it. We talked a while, had a long hug. She peered into the mei tai to see the top of Ben’s head. It’s rare to encounter people who say the words That sucks with loving attention and outrage. And how lovely it is to exhale like that. I have never forgotten it.

. . . . . . . .

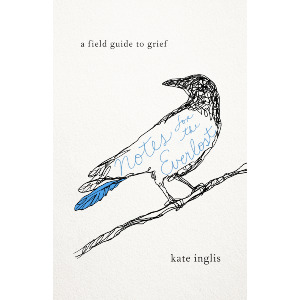

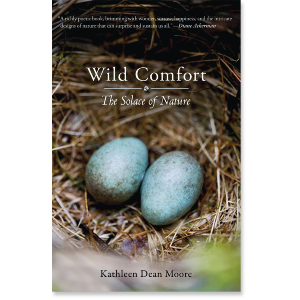

Related Books

$16.95 - Paperback

$19.95 - Paperback

$18.95 - Paperback

$18.95 - Paperback