The average American lies 25 times a day, according to recent statistics. Does Buddhism say that lying is always wrong? This excerpt, adapted from David Michie’s Buddhism for Busy People, takes a look at the surprising complexities of perfecting ethical behaviors.

Day one on your five-star African safari, and you and your friends are about to enjoy a banquet in the bush. It’s lunchtime on a balmy granite outcrop. You’re set up in the perfect spot—all cane furniture, white tablecloths and spectacular views. Everything seems perfect—until there’s a commotion, and a buck suddenly comes bounding through the undergrowth. Catching sight of the group, it immediately veers left, charging back into the elephant grass.

You’re a bit taken aback, but not unduly. But half a minute after the buck has disappeared, there’s another scramble through the bush—this time it’s a game warden that appears, followed by a panting, pink-faced hunter, rifle at the ready.

“Which way did it go?” they shout.

A simple question, but answering it isn’t so straightforward. And if you’re a Buddhist it could present you with a significant ethical dilemma. Do you create black karma by telling a lie? Or do you tell the truth, and assist in the likely killing of a sentient being?

This is not my ethical brain-teaser, but Buddha’s, one he used to illustrate the fact that ethical issues are often far from straightforward. Which does not excuse us from trying to practice ethics, but does recognize that lists of “dos” and “don’ts” aren’t always foolproof, and that there is a more important factor that should always be considered.

Buddhism encourages us to get real about ethics. While practicing the first perfection of generosity can be transformational, if generosity is combined with slippery ethics the end result is unlikely to make us happy. So closely are the first two perfections related that they are sometimes likened to a bird’s wings—both necessary to achieve lift-off.

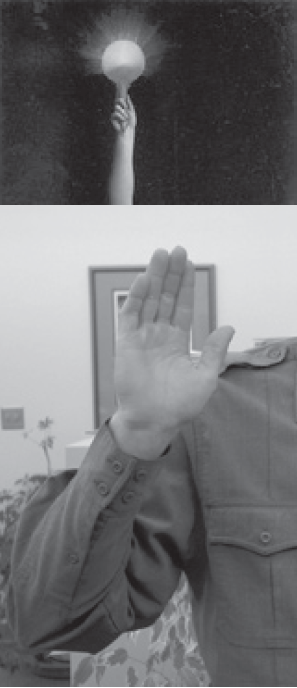

As Buddha suggested, there is nothing straightforward about ethics, even when we try to do the right thing. In the business world, notions like corporate responsibility, triple bottom line reporting, accountability and transparency suggest we are moving into a more ethical age. But the collapse of global accountancy firms, oil firms and IT companies remind us how easily ethical standards can be compromised. We might like to tell ourselves we do the right thing, but sometimes it’s only when a mirror is held up to our face that we are confronted by the unattractive truth.

Even if we want to do the right thing, we may be concerned that by adhering to high ethics we’ll put ourselves in a weak situation. If we work in an industry where everyone else “exaggerates,“ what will become of us if we don’t? If we reveal every source of income to the tax department, how can that possibly benefit us at the financial year end? The karmic pay-off in our next lifetime may be wonderful, but who is going to pay this year’s school fees?

Buddhism encourages us to analyze ethics from the perspectives of both the disadvantages of non-practice and the advantages of practice. To quote Geshe Loden, “The Buddha said that wishing for liberation but creating non-virtue is like a blind man looking in a mirror—a pointless exercise.” Just as the man’s visual handicap prevents him from seeing anything in a literal sense, an ethical handicap will prevent us from seeing the truth in our dharma practice. We can spend as many hours as we like in silent meditation, but if we also engage in duplicitous activities we might as well not bother.

The happiness that derives from ethics is not all about delayed gratification. People who are truly ethical—as opposed to merely sanctimonious—are frequently the most pleasant to be around. They are open, rather than guarded, because they don’t have to conceal things. They are relaxed, free from the concern that past actions may come back to haunt them. So the happiness that comes from good ethics isn’t all in the future, it is also here and now.

The practice of ethics is a vast subject within Buddhism, and includes eighteen root and 46 branch bodhichitta vows, starting with that most universally broken injunction against praising yourself and denigrating others. However, not even this framework provides all the answers to the troubling ethical issues that underlie contemporary headlines about economic refugees, stem cell research and nuclear waste disposal, let alone such age-old controversies as abortion and euthanasia.

Buddha did provide a useful principle, however, which he illustrated with his hunters and the buck story. In such circumstances, he said, the right ethical choice was to mislead the hunters about where the buck went in order to save its life. What really counts, he said, is motivation. The motivation to save the life of a sentient being is more important than the motivation to keep a vow of truthfulness which, in the circumstances, would have been a meaningless accomplishment.