An Excerpt from China Root

Ch’an practice was not simply about cultivating an abstract understanding of Taoist ontology/cosmology and the nature of consciousness; it was about actually living that understanding as a matter of immediate experience. And at the center of Ch’an practice was meditation. Indeed, Ch’an (禪), a transliteration of the Sanskrit dhyana, simply means “meditation.” (The original pronunciation of 禪 was dian, which makes more sense as a transliteration; but as with most Chinese words, the pronunciation changed over time.) The term was adopted as a name because Ch’an focuses so resolutely on meditation practice as the primary path to awakening.

The philosophical Taoism of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu was reenergized eight centuries after its origins by a philosophical movement known as Dark-Enigma Learning, which arose in the third century c.e. when Buddhism was becoming a major influence in Chinese culture. Its two major figures, Wang Pi (226–249) and Kuo Hsiang (252–312), articulated their thought in the form of commentaries on the seminal Taoist classics: I Ching, Tao Te Ching, Chuang Tzu. In these commentaries, they emphasized and deepened the ontological and cosmological dimensions of those seminal texts, and it was those dimensions that blended with newly imported Buddhism to create Ch’an. Or perhaps more accurately: newly imported Buddhism gave the Taoism of Dark-Enigma Learning an institutional setting and a form of actual practice.

In the official Ch’an legend, Bodhidharma brought Ch’an from India more or less fully formed around 500 c.e., but his teaching is clearly built from the traditional Taoist conceptual framework, a fact revealed most simply in the way he depends on terms and concepts central to that Taoist system. In fact, Ch’an’s origins are found a century or two earlier when Buddhist artist-intellectuals began melding Buddhism and Dark-Enigma Learning, which was broadly influential among artist-intellectuals at the time. In this process, they gave first form to most of the foundational elements of Ch’an that we will encounter in the following chapters. First among these, perhaps, is meditation.

The full transliteration of dhyana was Ch’an-na, 禪那. Of the many possible graphs that could have been chosen to transliterate dhyana, these would have been chosen for their Chinese meanings. 那 enriches meditative experience with its meanings “tranquility” and “that,” as in the immediacy of consciousness (“that”) in “tranquil” meditative experience. But 那 was dropped in normal usage, leaving 禪, a graph in which we can already begin to see the rich earthly and cosmological depths of Ch’an, for its pictographic etymology returns us to Taoist cosmology. And indeed, although it was the aspect of newly imported Buddhism most important to the development of Ch’an, dhyana meditation was reconceived according to China’s native Taoist framework.

Newly imported Buddhism gave the Taoism of Dark-Enigma Learning an institutional setting and a form of actual practice.

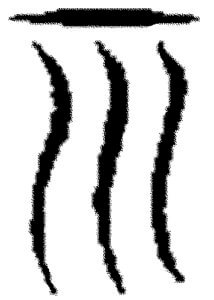

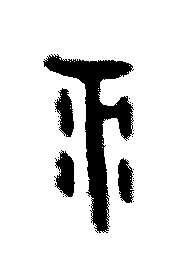

The 禪 graph divides into two elements: 礻 (示 in its full form) on the left, and 單 on the right. 示 derives from

The common meaning of 示 was simply “altar,” suggesting a spiritual space in which one can be in the presence of those celestial ch’i-sources. And indeed, if we were at a Ch’an monastery in ancient China, we would have experienced meditation as such a space, infused with those cosmological dimensions. It was also a practice of scientific observation, close empirical attention to the nature of consciousness (“seeing original-nature”) and its movements. As such, it was the most essential part of the Ch’an adventure, Ch’an’s primary method of awakening understood as “seeing original-nature.”

In bare philosophical outline, meditation begins with the practice of sitting quietly, attending to the rise and fall of breath, and watching thoughts similarly appear and disappear in a field of silent emptiness. From this attention to thought’s movement comes meditation’s first revelation: that we are not, as a matter of observable fact, our thoughts and memories. That is, we are not that center of identity we assume ourselves to be in our day-to-day lives, that identity-center defining us as fundamentally separate from the empirical Cosmos. Instead, we are an empty awareness that can watch identity rehearsing itself in thoughts and memories relentlessly coming and going. Suddenly, and in a radical way, Ch’an’s demolition of concepts and assumptions has begun. And it continues as meditation practice deepens.

With experience, the movement of thought during meditation slows enough that we notice each thought emerging from a kind of emptiness, evolving through its transformations, and finally disappearing back into that emptiness. Here, already, a new Taoist dimension is added to Buddhist dhyana meditation. Dhyana meditation, the conventional Buddhist form that came to China, cultivates consciousness as a selfless and empty state of “non-dualist” tranquility. Etymologically, dhyana means something like “to fix the mind upon,” hence meditation as fixing the mind upon emptiness and tranquility. This aspect of meditation was hardly unknown in ancient China, appearing for instance in this passage from the Chuang Tzu:

You’ve heard of using wings to fly, but have you heard of using no-wings to fly? You’ve heard of using knowing to know, but have you heard of using no-knowing to know?

Gaze into that cloistered calm, that chamber of emptiness where light is born. To rest in stillness is great good fortune. If we don’t rest there, we keep racing around even when we’re sitting quietly. Follow sight and sound deep inside, and keep the knowing mind outside.

But this must be seen in the Taoist context, as one aspect of meditative experience. And here at this stage in Ch’an meditation, we already find the Indian dhyana idea of meditation transformed by that context. We have moved beyond dhyana’s nirvana-tranquility and deep among Ch’an’s cosmological and ontological roots in Taoism, inhabiting a generative origin-moment/place in the form of “that chamber of emptiness where light is born.”

In Ch’an, the process of thoughts appearing and disappearing manifests Taoism’s generative cosmology, reveals it there within the mind. And with this comes the realization that the cosmology of Absence and Presence defines consciousness too, where thoughts are forms of Presence emerging from and vanishing back into Absence, exactly as the ten thousand things of the empirical world do. That is, consciousness is part of the same cosmological tissue as the empirical world, with thoughts emerging from the same generative emptiness as the ten thousand things.

We are not that center of identity we assume ourselves to be in our day-to-day lives, that identity-center defining us as fundamentally separate from the empirical Cosmos.

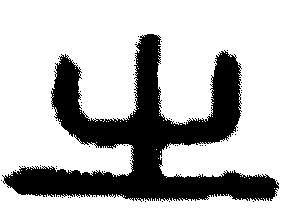

These ontological dimensions are suggested by the graph for monastery, where meditation took place: 寺. The pictographic elements of 寺 can be seen better in earlier forms such as

Eventually the stream of thought falls silent in meditation, and we inhabit empty consciousness free of the identity-center. That is, we inhabit the most fundamental nature of consciousness, known in Ch’an parlance as empty-mind or original-mind: original being 本, image of a tree (木, from earlier forms like

Sangha-Fundament (Seng Chao) and Way-Born (Tao Sheng) were the most important Buddhist intellectuals involved in the amalgamation of imported dhyana Buddhism and Dark-Enigma Learning. But perhaps the most concise and influential was Hsieh Ling-yün (385–433), a giant in the poetic tradition who was a very serious proto-Ch’an practitioner. Hsieh wrote a short essay entitled “Regarding the Source Ancestral,” described as an account of Way-Born’s teaching and apparently the earliest surviving Ch’an text, in part because it advocates the quintessential Ch’an doctrine of enlightenment as instantaneous and complete. This essay indicates that Hsieh had a profound grasp of Way-Born’s ideas and confirms that he had probably undergone a kind of Ch’an awakening himself. In it, Hsieh dismisses the traditional Buddhist doctrine of gradual enlightenment because “the tranquil mirror, all mystery and shadow, cannot include partial stages.” And from this comes a description of meditation’s fundamental outline that takes a decidedly Taoist form: “become Absence and mirror the whole . . .”

Though we will see it reappear and develop in a host of ways, Ch’an deconstruction is already complete here in Hsieh’s essay, and all the elements of awakening are in play. For we see as a matter of immediate observational experience the awakening suggested by Lao Tzu when he said: “if you aren’t free of yourself / how will you ever become yourself.” In this, already, we come to the foundational shift in awareness that is crucial to Ch’an awakening as “seeing original-nature”: the experience of oneself not as a center of identity inside its envelope of thought and memory, but as an empty mirror, the contents of which is wholly the world it faces. And more: “original-nature” as nothing less than Tao or Absence, the generative existence-tissue that is the wordless Cosmos whole. Indeed, Seventh Patriarch Spirit-Lightning Gather (Shen Hui)* described awakening as simply “seeing Absence” (見無), a variation on the Ch’an term we have seen for awakening: “seeing original-nature.”

Eventually the stream of thought falls silent in meditation, and we inhabit empty consciousness free of the identity-center.

At these cosmological levels, Ch’an meditation is anticipated in Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching, where much of the text describes meditative awareness, sometimes quite directly, as in: “Inhabit the furthest peripheries of emptiness / and abide in the tranquil center” or “sitting still in Way’s company.” And indeed, the Taoist cosmological dimensions of this “seeing original-nature” awakening are reflected in the graph for Ch’an itself: 禪. As we have seen, 禪 depicts in its left element (礻: 示 in its full form) those cosmological sources of ch’i radiating down as a sacred altar-space. The right-hand half of 禪 is 單, an element meaning “individual” or “alone,” a sense complemented by older meanings like “simple, great, entirely, exhaustively.” Together, these elements describe the fundamental experience of Ch’an meditation: “alone simply and exhaustively with the Cosmos.” With deeper meditation, this becomes “alone simply and exhaustively as the Cosmos,” and finally: “the Cosmos alone simply and exhaustively with itself.”

Note

* Spirit-Lightning Gather was Prajna-Able’s dharma-heir and the person most responsible for creating the image of Prajna-Able as the seminal Sixth Patriarch. Hence, in terms of the development of Ch’an thought, it appears Spirit-Lightning Gather himself articulated many of the seminal ideas attributed to Prajna-Able.

Share

Related Books

$19.95 - Paperback

Passing Through the Gateless Barrier

$34.95 - Paperback

$19.95 - Paperback

$19.95 - Paperback

$17.95 - Paperback