| The following article is from the Autumn, 1990 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

May All Be Auspicious: the Nuns of Lobsering

By Prema Dasara

Om Tashi Dondrup! The crisp morning air sparkled with their shouts as the group of men raised a tall wooden flagpole hung with prayer cloth. They were welcoming in another New Year in the Tibetan Refugee camp of Lobsering, India.

At every home in the small community the ritual would be repeated, the men running happily from place to place. The women of the household came out bearing a large, intricately carved, painted wooden box mounded with barley flour. Everyone took a pinch to toss and again chanted,

"Om Tashi Dondrup!–Please may this be a prosperous year!"

I had come to Lobsering to renew my connection with the students of Ani Jetsun Drolma. Ani Jetsun, the woman who through the strength of her practice manifested many remarkable abilities, had made her power accessible to the troubled Tibetan refugees in the camps of Orissa. Their lives had been so miserable then, having fled their native land for refuge in India.

"She was for the poor. Whatever you needed, she could help you get it, be it money, food, a place to stay, protection, comfort in our pain . . . she never let us feel hopeless."

The villagers did not see her often as she was always in retreat. However, when they climbed through the snake infested jungle to her hut they knew they would be helped. Her death in 1979, accompanied by rainbows and many miraculous signs, left her students struggling to maintain their practice in the face of extreme poverty.

"Come quickly!" Kyizom, the eldest daughter of Singye and Tseten Drolma tugged my sleeve. "Everyone is starting to gather on the hill."

Her parents had brought the plight of Ani Jetsun's students to the attention of a western nun, Karma Lekshe Tsomo. When I was visiting Lekshe in Dharamsala on my way to Orissa, she asked for my help. I went to Lobsering in 1988, wrote an article which was published in the Snow Lion Newsletter (A Life of Discipline, a Rainbow Death), and received some donations.

Another tug on my sleeve, and I turned around just in time to steady old Ani Pema who was struggling to maintain her balance in the dusty road. In one hand she brandished a wooden cane, in the other she waved a kata, the traditional white blessing scarf. At 78 years old the small donations we had sent her through the year had enabled her to remain independent. She had come to say her thanks.

At the top of the hill, five white parachutes had been erected, like sprouting mushrooms or exotic teepee umbrellas. The people of Lobsering are from different parts of Tibet, each having its own traditional prayers. They gathered under separate parachute umbrellas so that the whole camp could pray and feast together at the gathering but still maintain the individual traditions of their ancestors.

The maintenance of tradition is a high priority with the refugees. When His Holiness the Dalai Lama came to visit the camp he requested them to be strong and not give up their identity as Tibetans with a cultural heritage.

Throughout the year most of the able-bodied leave the camp in order to earn money, usually selling shoes or sweaters on the sidewalk in populated Indian cities. The elderly and the children stay behind to maintain the camps. But everyone comes home to celebrate Losar together.

Some children were running noisily up a small path to the left of the gathering. Kyizom and I followed them. A row of small rooms and a graceful stupa looked out over the fields and the distant, purple hills. This was the site of a three-year retreat center in the lineage of His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche.

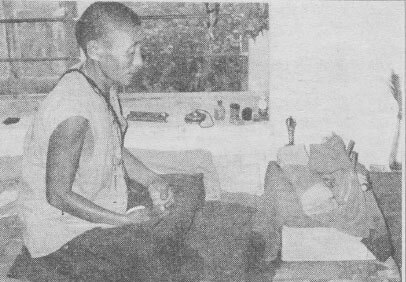

A group of monks had completed their retreat last year. Now Ani Tsultrim Palmo had been allowed to occupy one of the small rooms. She was sitting before her shrine, chanting softly when we arrived. She gestured to the modest offerings on her shrine.

"Your friends have made it possible for me to stay in retreat," she said. "I always offer part of everything I am given in their name."

We went outside and sat while she made a small fire for tea.

"Where will you cook when the rains come?" I asked. "Where will you go when the monks come for retreat?" She smiled.

"I will deal with things as they arise," she assured me. We watched the late afternoon sun cast its long shadows and relished Ani Palmo's serenity.

People had dispersed to their own family celebrations as we made our way through the jungle to Ani Kadak's hut. She was going to the village to perform a Tara puja for a family but she paused when she saw us coming.

"Ani-la, is there anything that we can do to make you more comfortable?" I asked, a question I would repeat to each of the women we are supporting. She was so poor; her hut was dark and ramshackle, empty of anything we could call comfort.

Ani Tsultrim Palmo, Lobsering, India.

"Yes," she said, "the farmers have put a fence across my path. It is difficult to get my water buckets over." I could easily imagine that. Ani Kadak is 73. She hauls water a quarter of a mile uphill. She does not want us to move her to a better spot. It is peaceful in the jungle.

"Ani-la," I ventured, "your blanket is full of holes. May I get you a new blanket?"

"No," she said, "it is not good to have too much. What I have is plenty. Besides, I am an old woman. I will die soon. What will happen to that new blanket then?" She laughed and walked us down the path as darkness settled softy over the camp.

Suddenly, up roared Singye on a blazing red Rajdoot motorcycle. "I borrowed it," he said. "There is dancing in camp #5."

Kyizom and I climbed aboard and off we went, down winding cattle trails and over rattling bridges through the velvet blackness. After some time there were lights and the laugh of children. We could hear the singing, first the men, then the women.

Circling in ceremonial steps, chanting an epic of their people, the men wore high hats with different colored flags while the women were crowned with flowers. The dancing went on and on . . . The people dreamt of a land of abundance and high mountain passes. They remembered the days of heroes and freedom.

The next day, fortified by the ever-full cup of steaming butter tea, I visited the other nuns to whom we had been sending donations.

Ani Tsultrim Wangmo was standing in the courtyard of her sister's house. She told us she was going to Nepal to see her teacher, His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. I asked her how she was going to get there.

"Someone will provide," she replied.

"Where will you stay? What will you eat?"

"I will beg," she replied.

"Is there anything we can give you for your journey?"

She smiled and shook her head slowly. The radiance of her face took my breath away.

Ani Tenzin Drolma was very happy at the old people's home. Singye gave her some rupees from our fund for medicine and for making offerings at her shrine during the holy days.

Ani Tsering Drolma requested a cooking pot. She had only one and wanted to cook her rice and vegetables separately.

Ani Yountro wanted to help with our prayer flag project so we wandered back to Singye's house where a small crowd had gathered. Singye was covered with black ink. So was the wooden block carved with mantras and auspicious animals. Now if all that enthusiasm could be transferred to the bright cloth stretched out before us, we'd be in business.

I packed my bag slowly. This visit had flown by. As I stood to leave, Singye filled my tea cup yet another time. When I protested he informed me that I wasn't to drink it. "This is so that you will come back," he said.

We walked down the road together, sounds of merriment coming from a neighbour's house. We caught up with Ani Pema, cane in one hand, bucket in the other, on her way to the well at the edge of the camp.

"Ani-la," I told her, "Please go to the Tibetan doctor. We have made an arrangement with him to give you medicine for your arthritis."

She shook her cane at me. "I am not going to take any more medicine," she said. "I am too old. I will die soon. I have no need for medicine. But I am telling you, we will all meet in Dewachen."

The bus approached, banging and rattling down the road. I had a fourteen-hour ride ahead of me, and the bus was packed to the gills.

A young Tibetan called my name and gestured me to his seat. I remembered meeting him at Singye's house. He was in the Indian army, stationed on the Ladakh border at 20,000 feet. He had walked up the road several miles in order to save a seat for me.

"The fare is paid," he said as he struggled to exit through the packed and seething multitude. My eyes filled with tears.

"Tashi Deleg!" Tseten Drolma shouted over the din, "may all be auspicious!"

Prema Dasara

Click on donations and/or humanitarian aid to see current projects with the Tara Dhatu Charity Fund. Donations are tax deductible.

"Tara Dhatu, which means the pure realm of the Goddess Tara."—Prema Dasara, Spiritual and Creative Director, Tara Dhatu