See our other Year in Review Guides:

Zen and Chan | Tibetan Buddhism | More in Buddhism

Yoga | Kids Books

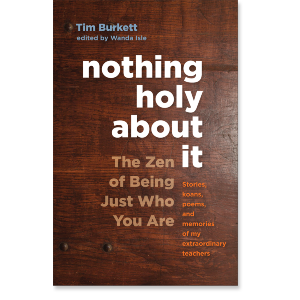

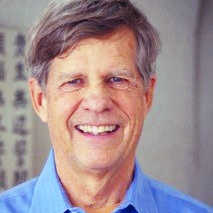

Tim Burkett

Tim Burkett began practicing Zen Buddhism in San Francisco in 1964 with renowned teacher Shunryu Suzuki. He is the former CEO of the largest nonprofit organization in Minnesota for individuals with mental illness and served as guiding teacher of Minnesota Zen Meditation Center from 2004 to 2021. He is a psychologist, a Zen Buddhist priest, and the author of Nothing Holy About It, Zen in the Age of Anxiety, and Enlightenment Is an Accident. He and his wife, Linda, have two grown children and two grandchildren.

Tim Burkett

GUIDES

Buy 2 books for 20% off, 3 books for 30% off, 4 or more for 35% off.

Applies to physical copies only, Discount applies automatically

We are very happy to share with you a look back at our 2023 books for those who practice in the Tibetan tradition.

Jump to: Reader Guides | Books | Books for Kids | Audiobooks | Forthcoming Books

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

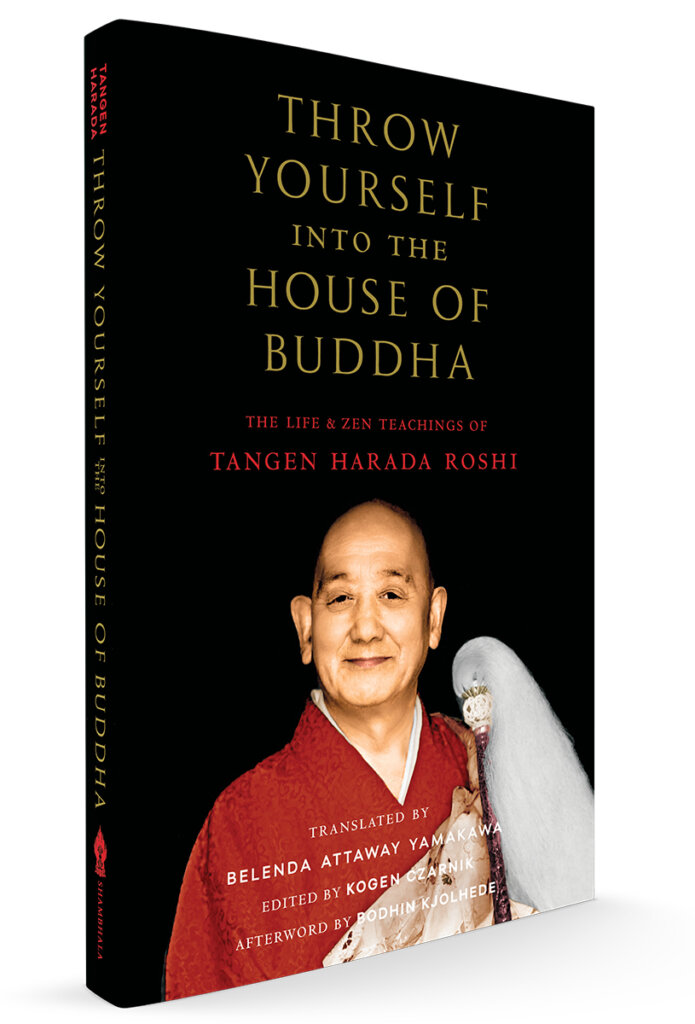

From narrowly surviving World War II through enduring the profound rigors of traditional Zen training, Tangen Harada’s fascinating life story and teachings present a classic picture of the Buddhist journey from suffering to realization.

On August 15th, 1945, at the age of twenty, Tangen Harada stood on an airfield and prepared to board the airplane on which he would undertake a suicide mission for his country. Only the voice of Emperor Hirohito on the radio—never before heard by the Japanese public—announcing Japan’s surrender saved his life. After returning from a Soviet POW camp in 1946, overcome with questions about the meaning of human life and suffering, Harada sought out the counsel of a Zen master. He thus embarked on the path of awakening and liberation to which he would commit the rest of his life, eventually teaching thousands of people from around the world.

Throw Yourself into the House of Buddha includes Tangen Roshi’s life story in his own words, as well as twenty-four teachings conveying the heart of his Zen understanding. Each chapter, paired with a beautiful calligraphy by the master, conveys his direct, uncompromising, yet encouraging message about the possibility of Zen realization.

“Wake up,” writes Harada, “and you can say for yourself, ‘The sun is my eye, the wind my breath, all of space my heart, the mountain and ocean my body. The sun shining brightly, vividly, is the eye of my life. The vastness of the sky is my heart.’ Who is the master of this boundless heart? No one else but you. This is your reality. Heaven and earth—same root, all things—one body.”

Paperback | Ebook

$27.95 - Paperback

The Way of Ch’an: Essential Texts of the Original Tradition

By David Hinton

This landmark anthology illuminates the true story of Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism’s historical development in China. Here we have the essential source material in its own native understanding, free of the mistranslation and misrepresentation that has characterized it in the modern West. As such, The Way of Ch’an offers a revolutionary understanding of Ch’an as a Buddhist-inflected form of Taoism, China’s native system of spiritual philosophy.

This authentic Ch’an was a radical and wild practice cultivating a deeply ecological form of liberation: the integration of mind and landscape/earth/Cosmos. Hinton’s accessible introductions guide us through texts that build from seminal Taoism through all stages of classical Ch’an—a tradition of zany and profound sages revealing Ch’an’s original form of awakening each in their own way. It’s a roller-coaster of voices and insights across thousands of years: The Way of Ch’an is a thrilling ride.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

By Andy Karr, foreword by Matthieu Ricard

While not explicitly a book on Zen practice, Into the Mirror is a call, based on Mahayana Buddhism, to cultivate wisdom and compassion—right within this world of illusion—and an insightful challenge to the rampant materialism of modernity. Andy Karr presents accessible and powerful methods to accomplish this through investigating the way our minds construct our worlds.

Combining contemporary Western inquiries with classical Buddhist investigations into the nature of mind, Karr invites the reader to make a personal, experiential journey through study, contemplation, and meditation. He presents a series of contemplative practices from Mahayana Buddhism, starting with the Middle Way teachings on emptiness and interdependence, through Yogachara’s subtle understanding of nonduality, to the view that buddha nature is already within us to be revealed rather than something external to be acquired.

Paperback| Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

A modern guide to the transformative practice of silent illumination from Chan Buddhist teacher Rebecca Li.

Silent illumination, a way of penetrating the mind through curious inquiry, is an especially potent, accessible, and portable meditation practice perfectly suited for a time when there is so much fear, upheaval, and sorrow in our world. It is a method of reconnecting with our true nature, which encompasses all that exists and where suffering cannot touch us.

The practice of silent illumination is simple, allowing each moment to be experienced as it is in order to manifest our innate wisdom and natural capacity for compassion. It can be integrated into all aspects of daily life and is meaningful for secular and Buddhist audiences, new and seasoned meditators alike.

After guiding readers through the history and practice of silent illumination, Rebecca Li shows us how we can recognize and unlearn our “modes of operation”—habits of mind that get in the way of being fully present and engaged with life. Cultivating clarity on the empty nature of these habits offers us a way to unlearn and free ourselves from unhelpful modes such as harshness to self, perfectionism, quietism, striving for spiritual attainment, and more. Illumination offers stories and real-life examples, references to classic Buddhist texts, and insights from Chan Master Sheng Yen to guide readers as they practice silent illumination not just on their cushions, but throughout their lives.

Paperback| Ebook

$18.95 - Paperback

Turning Words: Transformative Encounters with Buddhist Teachers

By Hozan Alan Senauke, foreword by Susan Moon

A poignant portrait of spiritual relationships evoked through the remarkable words of Buddhist teachers, leaders, and trailblazers.

Across nearly forty years of practice in Zen and socially engaged Buddhism, Hozan Alan Senauke has had a range of remarkable encounters with Buddhist teachers and spiritual friends. Here are stories of moments in which someone’s words, actions, or presence opened his mind and heart. Touching on meditation, insight, social action, race, family, community, and more, these vignettes build like a chorus and convey lessons such as taking one’s work seriously without taking oneself seriously, letting things fall apart, and using oneself up on behalf of others. The book’s stories feature many of the great Zen teachers, engaged Buddhists, and global Buddhist leaders of our day, including Robert Aitken, Bernie Glassman, Shodo Harada, Dainin Katagiri, Jarvis Masters, Ven. Sheng Yen, Sulak Sivaraksa, and many more—with a special section devoted to the teachings of Senauke’s primary teacher, Sojun Mel Weitsman.

Paperback| Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

Opening to Oneness: A Practical and Philosophical Guide to the Zen Precepts

By Nancy Mujo Baker

Stop trying to become “better” by suppressing or hiding parts of yourself, and learn what it means to be fully human with this accessible guide to the core ethical teachings of Zen Buddhism.

In Opening to Oneness, Zen teacher Nancy Baker offers a detailed path of practice for Zen students planning to take the precepts and for anyone, Buddhist or non-Buddhist, interested in deepening their personal study of ethical living. She reveals that there are three levels of each precept: a literal level (don’t kill, not even a bug), a relative level that takes moral ambiguity into account (what if it’s a malaria-spreading mosquito?), and an ultimate level—the paradoxical level of nonduality, in which the precepts are naturally expressed from a state of oneness.

Full of nuance, intelligence, and compassion, the first half of the book addresses the ten grave precepts mostly from the relative level, including instructions for how to practice these precepts individually and in pairs or groups.

The second half of the book takes a deep dive into looking at the precepts from the ultimate perspective, largely through an exploration of the writings of Dogen, the thirteenth-century religious genius who founded the Soto Zen school.

At once comprehensive and innovative, Opening to Oneness will take its place alongside classics like The Mind of Clover, The Heart of Being, and Being Upright as a cherished guide to Zen Buddhist ethics.

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

A warm-hearted guide to Buddhist practice for those ready to contend with the reality that enlightenment—the realization of non-self—can’t be achieved by the self.

A well-known spiritual saying goes, “Enlightenment is an accident. But we can make ourselves more accident prone.” As an authentic American Zen takes shape, enlightenment continues to be misunderstood as a project to be completed, a goal to be achieved, or a prize to be awarded. Tim Burkett’s new book unhooks enlightenment from the hot air balloon of ego and brings it back down to earth.

Drawing on stories of his first teacher, the Zen master Shunryu Suzuki (author of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind), and Burkett’s decades of practice and teaching, he reveals how to live in the world with a deep joy that comes from embracing the work and play of this very moment. With the wisdom and humor of a seasoned practitioner familiar with all manner of eccentric fixations and silly dead-ends, he offers views and practices we can use to support the paradoxical process of letting enlightenment happen on its own.

Paperback | Ebook | Audiobook

$21.95 - Paperback

The Buddhist and the Ethicist: Conversations on Effective Altruism, Engaged Buddhism, and How to Build a Better World

By Peter Singer and Shih Chao-Hwei

An unlikely duo—Professor Peter Singer, a preeminent philosopher and professor of bioethics, and Venerable Shih Chao-Hwei, a Taiwanese Buddhist monastic of the Chan tradition and social activist—join forces to talk ethics in lively conversations that cross oceans, overcome language barriers, and bridge philosophies. The eye-opening dialogues collected here share unique perspectives on contemporary issues like animal welfare, gender equality, the death penalty, and more. Together, these two deep thinkers explore the foundation of ethics and key Buddhist concepts, and ultimately reveal how we can all move toward making the world a better place.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

A Fire Runs through All Things: Zen Koans for Facing the Climate Crisis

By Susan Murphy

At a time of climate emergency, Zen koans show us how crisis itself can reveal the regenerative openness of life, mind, and being.

Zen koans are a tradition of holistic inquiry based on “encounter stories” from East Asia’s most radical Buddhist tradition. Turning this form of inquiry toward the climate crisis, Susan Murphy contends that koans can help us enter the mind of not-knowing, from which acceptance and possibility freely emerge. Koans reveal intimate, mythic, artful, playful, provocative, humorous, and fierce ways to engage the work of protecting and healing our world.

The koans point firstly at ourselves—at the very nature of "self." Until we hold “self” as a live question rather than its own unquestioned answer, we’re stuck looking on from the “outside,” hoping to engineer change upon a problem called “climate crisis,” all the time oblivious to the fact that we’re swimming in a reality with no outside to it, an ocean of transformative energy. Do we dare relinquish our wish for absolute control and fearlessly surf the intensity of our feelings about the suffering earth?

In addition to her use of dozens of traditional and new koans, Murphy illuminates the little-known Zen resonance with the oldest continuous body of indigenous wisdom on earth, summed up in the subtle Australian Aboriginal word Country. Murphy draws from her study and coteaching with Uncle Max (Dulumunmun) Harrison, a distinguished Yuin Elder, to show how this millennia-deep taproot of intelligence confirms the aliveness of the earth and the kinship of all beings.

Hardcover | Ebook

$19.95 - Hardcover

Accessible and adaptable Japanese Buddhist rituals to infuse your life with purpose, healing, and gratitude when you need it most.

How do we make and sustain meaning amidst the messy conditions of daily life? Personalized rituals can help us blossom like lotuses right in the mud of the present. On a pilgrimage she began after her mother’s death, author Paula Arai encountered numerous Japanese Buddhists who taught her the remarkable power of ritual to heal—practices you can adapt to your own cultural and personal circumstances. Applying principles of Zen practice, she offers stories and insights that illuminate how to nourish and reap a healing bounty of connection, joy, and compassion. Examples include how to:

- Relate to a late loved one as a “personal Buddha” who supports you

- Create a home altar to serve as a safe space to be vulnerable, face intense emotions, and experience a depth of warm gratitude that melts fear and anger

- Engage in daily tasks with attentiveness, intention, and creativity such that they become opportunities for body-mind integration

- Develop family rituals to celebrate relationships and mark transitions

- Approach illness and grief with a purposeful sense of connection to life-and-death in its wholeness

Like Marie Kondo's Shinto principles for decluttering, Paula Arai uses rituals influenced by Japanese Zen for personal and relational nourishment and spiritual healing.

Card Deck

$27.95 - MixedMedia

In a Moment, in a Breath: 55 Meditations to Cultivate a Courageous Heart

By Roshi Joan Halifax

“In a moment, in a breath, we can drop in and have the wherewithal to meet whatever the moment is offering.”

Featuring the original artwork of Roshi Joan Halifax, this collection of cards offers short and powerful meditative practices that allow you to tune in, still the mind, and cultivate courage—in just a moment’s time.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

An accessible, compassionate guide to Buddhist principles and practices that can help support recovery from addictions and addictive behaviors—written by an experienced lay teacher with long-term recovery.

For anyone struggling with addiction, Buddhism offers powerful, grounding wisdom and tools to help support recovery. In The Zen Way of Recovery, Laura Burges shares her experience as a dedicated Zen practitioner who came to terms with her own addiction to alcohol and found support for her recovery. Through the lens of Buddhist teachings, Burges offers tools and practices which, together with the help of recovery programs, can offer a road to sobriety.

Burges is an experienced and compassionate guide, and her message is resonant for people with any type of addictive behavior—and for people who aren’t necessarily familiar with Buddhism. Her teachings are drawn from the Buddha's life and teachings (specifically the Eight Awarenesses of the Awakened Being and the Six Paramitas), and the wisdom of Japanese Buddhist priest Dogen Zenji, the founder of the Soto school of Zen, among others.

Burges emphasizes the importance of being in an active recovery program, and the teachings and practices she offers in each chapter—including reflections, journaling prompts, meditations, instructions for setting up an altar, and a simple guide to zazen—are both a perfect adjunct and powerful reinforcement.

Examples of reflections and journaling prompts include:

- Do you still hear the critical, contemptuous, sarcastic voice of a parent or partner in your own head?

- Do you sometimes hear yourself mirroring this negative voice with others?

- What were the models of relationship that you grew up with?

- What are ways that you can cultivate more patience?

- Check in with yourself to see if tiredness, hunger, loneliness, or anger is affecting your thinking in the moment.

Paperback | Ebook

$18.95 - Paperback

Zen-inspired activities and stories to help kids learn about patience, kindness, honesty, sharing, and forgiveness.

Have you ever heard the word Zen? It’s what happens when you sit quietly, noticing your breath and what it feels like to just be alive. Zen is a way of closely looking at our life and the world around us so that we can share love and compassion with everyone and everything!

Each chapter has a new story to explore, with themed discussion questions, meditations, journal prompts, and hands-on projects.

Make Zen a part of your everyday life with this fun and friendly guide!

Rebirths: New Editions of Classics

Paperback | Ebook

$16.95 - Paperback

Paperback | Ebook

$14.95 - Paperback

Paperback | Ebook

$16.95 - Paperback

Paperback | Ebook

$14.95 - Paperback

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

2023 Books Related to Chan and Zen

Forthcoming in 2024

And we have even more from the Chan and Zen traditions coming out next year from the likes of Yamada Mumon Roshi, James Ford, Nelson Foster, Cristina Moon, David Hinton (a new translation of the Blue Cliff Record), Korean Soen teacher Barbara Rhodes, Gerry Shishin Wick (on the Five Ranks), Kaz Tanahashi on the Zen gardens of Kyoto, and more. So make sure you sign up for our emails so you do not miss them! Here is a sneak peek at our first 2024 release which you can pre-order now and take advantage of the discount.

Paperback | Ebook

$24.95 - Paperback

Hakuin’s Song of Zazen: Yamada Mumon Roshi on Zen Practice

By Yamada Mumon Roshi, foreword by D. T. Suzuki, translated by Norman Waddell

Renowned modern Zen master Yamada Mumon Rōshi uses Hakuin’s famous poem of spiritual realization, Song of Zazen, as a starting point to embark on a lively commentary on Zen practice in contemporary life.

First published in Japan in 1962, Hakuin’s Song of Zazen is a celebrated collection of short essays by Zen master Yamada Mumon Rōshi. Translated into English for the first time, it introduces the story of Hakuin’s early life and training, then uses his classic Zen chanting poem, Song of Zazen, to make wide-ranging considerations of the Zen tradition and its applications in modern Japanese life.

As Daisetz Suzuki remarks in his foreword, what gives Mumon’s book its unique flavor and makes it different from previous works by Zen teachers are his forays into matters of ordinary, everyday life, expanding his Zen teaching to encompass interests that are closely linked with his lay audience. He responds to a news article that catches his eye in the morning paper, delivers criticism on contemporary political and social trends, explores matters as diversified as the uses of atomic energy, the court culture of seventeenth-century France, a leper hospital on an island in the Inland Sea, Albert Schweitzer and other noted Western figures—and more. In doing this Mumon gives readers open access to the opinions, judgements, and practical thinking of a leading Zen master—a map of his planet, so to speak. Each brief chapter of Mumon’s book is an invitation to follow Hakuin and himself down the path of true Zen realization.

Zen in Japan: Up to the Meiji Restoration

Zen in Japan: Up to the Meiji Restoration

This is part of a series of articles on the arc of Zen thought, practice, and history, as presented in The Circle of the Way: A Concise History of Zen from the Buddha to the Modern World. You can start at the beginning of this series or simply explore from here.

Explore Zen Buddhism: A Reader's Guide to the Great Works

Overview

Chan in China

- The Works of the Chan and Zen Patriarchs

- The Works of Zen in the Tang Dynasty (618-907)

- The Works of Zen in the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279)

- The Great Koan Collections

Zen in Korea

Zen in Japan

- Early Zen in Japan

- Dogen: A Guide to His Works

- Rinzai Zen

- Hakuin Ekaku: A Reader's Guide

- The Samurai and Zen

> Zen in Japan up to the Meiji Restoration

Additional Resources

- The Heart Sutra: A Reader’s Guide

- Zen in the Modern World (Coming Soon)

- Foundational Sutras and Texts of Zen (Coming Soon)

- Zen and Tea

The period after Dogen and the early period of Zen saw rich developments, including of course the Rinzai school and the Samurai which are covered in the sister guides to this article. Here are some of the works we publish from after the early period up to the 19th century Meiji Restoration when changes in power made for a more challenging environment for Zen practitioners and institutions throughout Japan.

Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record: Zen Comments by Hakuin and Tenkei

Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record is a fresh translation featuring newly translated commentary from Hakuin of the Rinzai sect of Zen and Tenkei Denson (1648–1735) of the Soto sect of Zen.

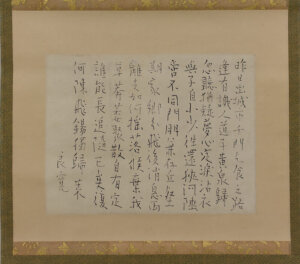

Ryokan

Chinese Poem Lamenting the Death of a Friend by Ryokan from the Met

Ryokan (1758–1831) is, along with Dogen and Hakuin, one of the three giants of Zen in Japan. But unlike his two renowned colleagues, Ryokan was a societal dropout, living mostly as a hermit and a beggar. He was never head of a monastery or temple. He liked playing with children. He had no dharma heir. Even so, people recognized the depth of his realization, and he was sought out by people of all walks of life for the teaching to be experienced in just being around him. His poetry and art were wildly popular even in his lifetime. He is now regarded as one of the greatest poets of the Edo Period, along with Basho, Buson, and Issa.

Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan

He was also a master artist-calligrapher with a very distinctive style, due mostly to his unique and irrepressible spirit, but also because he was so poor he didn’t usually have materials: his distinctive thin line was due to the fact that he often used twigs rather than the brushes he couldn’t afford. He was said to practice his brushwork with his fingers in the air when he didn’t have any paper. There are hilarious stories about how people tried to trick him into doing art for them, and about how he frustrated their attempts. As an old man, he fell in love with a young Zen nun who also became his student. His affection for her colors the mature poems of his late period. This collection contains more than 140 of Ryokan’s poems, with selections of his art, and of the very funny anecdotes about him.

Dewdrops on a Lotus Leaf: Zen Poems of Ryokan

Deceptively simple, Ryokan's poems transcend artifice, presenting spontaneous expressions of pure Zen spirit. Like his contemporary Thoreau, Ryokan celebrates nature and the natural life, but his poems touch the whole range of human experience: joy and sadness, pleasure and pain, enlightenment and illusion, love and loneliness. This collection of translations reflects the full spectrum of Ryokan's spiritual and poetic vision, including Japanese haiku, longer folk songs, and Chinese-style verse. Fifteen ink paintings by Koshi no Sengai (1895–1958) complement these translations and beautifully depict the spirit of this famous poet.

One Robe, One Bowl: The Zen Poetry of Ryokan

The hermit-monk Ryokan, long beloved in Japan both for his poetry and for his character, belongs in the tradition of the great Zen eccentrics of China and Japan. His reclusive life and celebration of nature and the natural life also bring to mind his younger American contemporary, Thoreau. Ryokan's poetry is that of the mature Zen master, its deceptive simplicity revealing an art that surpasses artifice.

Ikkyu

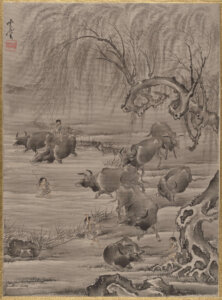

Twilight Landscape

In the Style of Ikkyū Sōjun Japanese. From the Met.

Finally, there is the figure of Ikkyu (1394–1481). While we do not have any stand-alone works on or by him, he appears in many, many works. In The Circle of the Way, he gets a few pages that begins:

Of all Muromachi-period Zen monastics, with all of their talent and accomplishments, the monk most well known today was something of a black sheep. Ikkyu Sojun (1394–1481) remains so popular in Japan that he has been portrayed in anime and the popular graphic art of manga.

Peter Matthiessen, In Nine-Headed Dragon River: Zen Journals, adds more color with his flowing prose, describing him as

A bastard son of the emperor, pauper, poet, twice-failed suicide, and Zen master, enlightened at last by the harsh call of a crow. At eighty-one Ikkyu became the iconoclastic abbot of Daitoku-ji. ('For fifty years I was a man wearing straw raincoat and umbrella-hat; I feel grief and shame now at this purple robe.') His 'mad' behavior was perhaps his way of disrupting the corrupt and feeble Zen he saw around him: 'An insane man of mad temper raises a mad air,' he wrote. He also said, 'Having no destination, I am never lost.' One infatuated scholar has called him 'the most remarkable monk in the history of Japanese Buddhism, the only Japanese comparable to the great Chinese Zen masters, for example, Joshu, Rinzai, and Unmon.' Ikkyu found no one he could approve as his Dharma successor. Before his death, civil disorders caused the near obliteration of Kyoto, forcing Rinzai Zen to follow Soto from the decadent capital city into the countryside.

by Jim Harrison

A collection of poems inspired by Ikkyu by the great novelist and essayist Jim Harrison who said of this work,

The sequence After Ikkyu- was occasioned when Jack Turner passed along to me The Record of Tungshan and the new Master Yunmen, edited by Urs App. It was a dark period, and I spent a great deal of time with the books. They rattled me loose from the oppressive, poleaxed state of distraction we count as worldly success. But then we are not fueled by piths and gists but by practice—which is Yunmen’s unshakable point, among a thousand other harrowing ones. I was born a baby, what are these hundred suits of clothes I’m wearing?

Naked in the Zendo: Stories of Uptight Zen, Wild-Ass Zen, and Enlightenment Wherever You Are

While not by Ikkyu, he makes an appearance in this work over a few very entertaining and moving pages.

Zen in the Age of Anxiety: Wisdom for Navigating Our Modern Lives

Ikkyu makes an appearance for several pages of Tim Burkett's excellent work which includes translations, by John Stevens, of several of his poems

You Have to Say Something: Manifesting Zen Insight

Dainin Katagiri Roshi shares this story about Ikkyu in this work:

A man who was soon going to die wanted to see Zen master Ikkyu. He asked Ikkyu, ‘‘Am I going to die?’’ Instead of giving the usual words of comfort, Ikkyu said, ‘‘Your end is near. I am going to die, too. Others are going to die.’’ Ikkyu was saying that we can all share this suffering. Persons who are about to

die can share their suffering with us, and we can share our suffering with those who are about to die.Ikkyu’s statement comes from a deep understanding of human suffering. In facing your last moment, you can really share your life and your death.

Minding Mind: A Course in Basic Meditation

One of the meditation manuals in this work date from pre-Meiji Restoration Japan.

The second, An Elementary Talk on Zen, is attributed to Man-an, an old adept of a Soto school of Zen who is believed to have lived in the early seventeenth century. The Soto schools of Zen in that time traced their spiritual lineages back to Dogen and Ejo , but their doctrines and methods were not quite the same as the ancient masters’, reflecting later accretions from other schools.

Man-an’s work is very accessible and extremely interesting for the range of its content. In particular, it reflects a modern trend toward emphasis on meditation in action, which can be seen in China particularly from the eleventh century, in Korea from the twelfth century, and in Japan from the fourteenth century.

Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice

This recent work by Professor Charles B. Jones, a leading scholar on Pure Land Buddhism, goes into much detail of Pure Land and its intertined relationship with Zen. The sections on Japan include its introduction from China, Ryonin and the Yuzi Nenbutsu, Honen and Jodo Shu, Shinran and the Jodo Shinshu, and Ippen and the Jishu.

Continue to our next article in the series: A Readers Guide to the Heart Sutra >

This holiday season we care about hearing what you have to say. Below are some thoughtful quotations from readers on their favorite Shambhala books.

Do you have one you'd like to share? Tell us about it in the comment section at the bottom.

“The book can be taken literally as a way to master ancient samurai techniques, or it can be taken metaphorically on how to manage business or political deals.”

—Rachel

“This book has made its way from my bookshelf to my bedside table numerous times over the years.”

—Shelley

“Sharon Salzberg has a true gift for putting into words and examples the teachings of the Buddhist path so that it is clear they truly do apply to everyday life.”

—Dominique

“A brilliant book documenting the social, emotional, physical, psychological, and cultural changes happening to women during the massive transformation that is becoming a new mother.”

—Sarah

“Chödrön speaks to anyone who’s willing to stick with her as she explores what becoming a bodhisattva means. She points out examples of bodhisattvas, including Jesus, Mother Teresa, MLK, and Gandhi, who may be more relatable to her Western readers than Shantideva or various monks in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.”

—Linsey

“I found myself underlining, copying quotes, and going back to ponder ideas and applications, over and over.”

—Judy

“His genius of integrating our history of religion and their great traditions gives a greater vision for how we, as humans, may better live this vision by deepening connections to our sameness as we move up the developmental ladder of our differences, where we embrace a greater, higher love that clearly drives our entire existence and evolution.”

—Mary

“Kristin gives clear, excellent directions for a variety of crafts, including sewing, painting, embroidery, and fabric stamping, and helps her readers understand how to combine colors and patterns to achieve glorious results.”

—Ferguson

$35.00 - Hardcover

“If you love colorful, healthy food with a unique twist, then this is for you.”

—Roberta

“What I especially enjoy about this book is that it explains, in clear, easy to understand language, what happens to our bodies as we age and how yoga can help us live a life of greater ease.”

—Rosemary

“Sculpted with tenderness, beauty, and lyric storytelling, Kate Inglis walks the reader gently and lovingly through the process of grief by bearing her own heart, her own soul, and her own loss.”

—Siobhan

“The More With Less cookbook is now my all time favorite/go-to cookbook for both everyday meals and special dinners for friends and family.”

—Patricia

“Natalie fans will be transfixed and unnerved by this honest narrative of the cancer experience.”

—Jerser

“Looking at our natural human fears through the lens of Zen Buddhism, Burkett takes us into the areas of our deepest pains and guides us on how to process and release them by looking inward through meditation.”

—Kathy

“Training in Tenderness is an insightful, practical guidebook on how to soften the heart and be more in touch with the world around us.”

—Jim

“This book is an invitation to investigate your assumptions and explore the interdependence of everything.”

—Christine

“Every page is a delight to the eye and makes you want to get out those art supplies and start painting!”

—Bob

“Jacobs takes you to faraway places and makes you want to dust off your suitcase and book a trip immediately.”

—Maria

“Here's what I love most about this book: even if you have precisely zero experience with any part of printing your own fabric patterns, you'll get everything you need to get started.”

—Elizabeth

“A very cute book if you are into embroidery and looking for some inspiration, or trying some new stitches.”

—Javiera

Being Human | An Excerpt from Zen in the Age of Anxiety

Wisdom for Navigating Our Modern Lives

I can’t get no satisfaction

’Cause I try and I try and I try and I try

I can’t get no, I can’t get no

Satisfaction

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction

The Rolling Stones’s first big hit in the United States was “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” and is still considered by many the greatest song they ever recorded. It made the charts in 1965. I was in my fourth year at Stanford University, on the supposed fast track to success and happiness. I’d been born into an upper middle class family, I lived in the beautiful and prestigious San Francisco Bay Area, and I never gave more than a moment’s thought to the concerns about money and economic status that the previous generation had worried about during the post–World War Two era.

So you may be wondering why the lyrics of that classic Stones song would resonate so deeply with me and my generation. The reason is that, in the sixties, there was more going on than just the restless angst of a privileged generation. Younger Americans were among the first to deeply question the decisions coming out of Washington and the aggressive international path our country had taken. The anguish and actions of college students and other young people around the country polarized the nation: Peace activists (including me) rallied against the Vietnam War while returning soldiers, with mangled bodies and war-weary eyes, were honored in parades and then forgotten. Angry and often violent polarization was reflected on streets and campuses, in our art, and in our music.

And that man comes on the radio

He’s tellin’ me more and more

About some useless information

Supposed to fire my imagination

The idea of the American dream, so fulfilling to my parents and grandparents, no longer nourished the hearts and minds of many in my generation. I tried, and I tried, and I tried, but I got no satisfaction—not as a peace activist, or a student, or at my job. I got a little satisfaction in love, but then we broke up. A little satisfaction from sex, but it didn’t last very long.

A year before “Satisfaction” came on my radio, I’d begun a meditation practice with Suzuki Roshi at the San Francisco Zen Center. For a while my heart was calm and peaceful, but when the dissatisfaction returned, it seemed deeper and more impenetrable than ever.

Meditation doesn’t save us from life’s trials and tragedies. In fact, Zen meditation allows us to enter completely both the joy and darkness that make up this great life. Deep healing often begins in darkness, in times when we feel deep dissatisfaction and little or no vitality.

Meditation doesn’t save us from life’s trials and tragedies. In fact, Zen meditation allows us to enter completely both the joy and darkness that make up this great life. Deep healing often begins in darkness, in times when we feel deep dissatisfaction and little or no vitality.

The place of our deepest fears can be rich soil when it is entered into fully. As our eyes adjust to the dark, clear-seeing becomes possible. Standing firm in the darkness, without withdrawing or lashing out, we discover what motivates us in healthy, wholesome ways and what drives us to exhaustion and depression. We see for ourselves how fear-based thinking and emotional reactivity influence us individually and collectively. Fear is used by us and against us, and recognizing this truth is the first step toward healing.

This book offers an approach to life that opens us up to a new way of thinking and being in the world. The approach is not new, but too often confusing language, unfamiliar metaphors, and practices that confound and bewilder obscure it. This book is written in the style of an owner’s manual, a guide to being human, and begins by focusing on the four most troublesome areas that most of us are intimately familiar with: feelings of unworthiness, and issues surrounding sex, money, and failure. These are the outermost layers of the onion, and they must be penetrated with clear-seeing, generosity, and openness.

Year after year,

the monkey’s face

wears a monkey’s mask

—Basho, seventeenth century

Basho’s poem points to the difficulty of penetrating the onion by seeing through our fear-based thinking. But as I stayed with my meditation practice, I began to see through the layers to realize a direct correlation between the fear-based dramas playing out in my mind and my can’t-get-no-satisfaction life. Maybe you can, too.

One Step at a Time: The Footprint Stage of Practice

Every major religion includes contemplative practices that can move us beyond the confusion, disintegration, longing, and weariness associated with fear-based thinking. Often, however, we have to completely exhaust ourselves before we are ready to embark on this life-altering path.

Here in the United States, we are exhausting ourselves at a younger and younger age. I was twenty when I began my meditation practice. Meditation was an oddity then. But today more and more people are turning to this ancient practice to cope with the mental and emotional stress and weariness that have become hallmarks of American culture.

Maybe you’ve tried to meditate in the past but have lost your way and quit—perhaps repeatedly. It’s not an uncommon experience. Often people read or hear something inspiring and begin a regular practice. They’ve caught a glimpse of something meaningful, like rabbit tracks on the surface of new-fallen snow. But then the deeper teachings that support the practice become remote and incomprehensible, and the footprints fade away like tracks vanishing in falling snow.

Maybe you’ve tried to meditate in the past but have lost your way and quit—perhaps repeatedly. It’s not an uncommon experience. Often people read or hear something inspiring and begin a regular practice. They’ve caught a glimpse of something meaningful, like rabbit tracks on the surface of new-fallen snow. But then the deeper teachings that support the practice become remote and incomprehensible, and the footprints fade away like tracks vanishing in falling snow.

This is what I call the footprint stage of practice. When the tracks disappear, people become overwhelmed or discouraged and withdraw back into their frenzied life of dissatisfaction. Later, the tracks reappear, and for a time, the path is clearly marked. Repeatedly the footprints seem to disappear and reappear.

Eventually, you’ll come to realize that the tracks are everywhere—but always, the snow keeps falling and covering them up. Life is continuously unfolding in unlikely and unpredictable ways. Repeatedly, we seem to drift back into the dramas, anxieties, and worries of a fear-driven life. But this, too, may be the path. Each time we return, we are a little wiser and a little more sure-footed as we realize that the path is right where we are, even when the footprints fade from view. When the footprints are visible, we feel secure; when they vanish, we learn to trust. Even though the path is always here, the way we walk it is uniquely our own.

Our Movie-Making Mind

In 2015, forty-five years after I moved away from the Bay Area, I went back to promote my first book, Nothing Holy about It. One afternoon, I walked to Bush Street where the San Francisco Zen Center had been. It was now a senior center.

As I stood on the corner of Bush and Laguna, my mind was flooded with memories. I had practiced at the center for five years, from 1964 to 1969, with Suzuki Roshi, who became one of the most famous Zen teachers in the world. Five years may not seem like a long time to absorb Suzki’s teachings, but in the days before he was famous he had only a handful of devoted students, so I saw him frequently.

Thinking back to those days, I looked through a window into the room where the auditorium used to be, where on Saturday evenings Suzuki watched imported movies with his Japanese congregation. Then on Sunday mornings he would give dharma talks for his small group of American students. The Japanese congregation didn’t meditate or go to his dharma talks. In Japan, only the monks living in monasteries meditated and studied the teachings.

Each day as I entered the building for morning meditation, I passed a giant poster advertising the upcoming movie. A typical poster featured swords dripping with blood, decapitated limbs, and geishas in distress. These looked like pretty lousy movies by my standards. When I wanted some entertainment, I went to North Beach, where they showed artistic movies that had some depth and were emotionally moving. I felt bad that my teacher had to watch those B-rated imports.

One Sunday morning Suzuki looked tired.

“Do you have to watch movies every Saturday night?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” he said, cheerfully. “We watch movies together on Saturday nights.”

“I’m sorry you have to watch those movies. Do you like any of them?” I asked.

“I like them all,” he said.

He liked them all? Apparently my teacher was pretty unsophisticated when it came to movies.

This was during a time when my Zen practice had become very difficult. It was my can’t-get-no-satisfaction phase, and all sorts of memories and fears were coming up in my meditation. Over and over, I relived past dramas and projected them into the future, rehearsing how I wanted to be different. The stillness and joy I’d experienced my first few months of Zen practice had vanished. I seemed to have no control over the images that cycled through my mind, on and off the cushion.

“I like them all,” was a teaching that I didn’t recognize until much later. Even though I didn’t understand the significance of those four words at the time, they stayed with me. Suzuki wasn’t judging the movies he saw. He wasn’t comparing them to the artsy films playing at North Beach. He was simply present, attentive, and engaged. This was his way.

“I like them all,” was a teaching that I didn’t recognize until much later. Even though I didn’t understand the significance of those four words at the time, they stayed with me. Suzuki wasn’t judging the movies he saw. He wasn’t comparing them to the artsy films playing at North Beach. He was simply present, attentive, and engaged. This was his way.

Today, people say that Suzuki Roshi was a great enlightened being, but I don’t know about that. He lived lightly, joyfully. That is what I remember most about him. It’s what drew me to him and continues to draw me to him, though now he lives only in my heart.

“I like them all” was a footprint along my path, one that disappeared and reappeared, over and over, until I finally got it. I realized that I could be present and attentive to the movies inside my head without getting caught up in which ones were good and which were bad.

I think this is a challenge that most of us face. We create movies in our heads to try to make sense of the world and of what’s happening around us. But these movies are based on our memories of past experiences, and if they’re so dense we can’t see beyond them, they tether us continually to the past.

We can learn something about ourselves if we look closely at these movies and recognize their genres and themes. When we’re fearful, our movies may be tension-filled dramas. When moody or anxious, gloomy melodramas. For many people, ghost stories are a favorite genre. Here’s one of mine:

In the mid-sixties, there weren’t many of us meditators, so I got to hang out with Suzuki as much as I wanted. Then we purchased Tassajara Zen Mountain Monastery, and more and more people came to practice with him. Things began to change.

I had a friend whom I’ll call Louise. She was a serious Zen student, and I appreciated her sincerity. But after a while it seemed that she was dominating Suzuki’s time and I began to appreciate her less and less. Whenever I saw her, I was overwhelmed with jealousy and confusion.

Finally, I realized what was going on. In this situation Louise was like my sister, and I was jealous of my sister my whole life because my dad seemed to give her more time and attention than me. I became aware that the movie I’d created so many years ago was now playing out even here in this calm, monastic setting, dedicated to the cultivation of stillness, compassion, and deep inner joy. I was trying my best to live in today—but memory ghosts swirled around me, separating me from what was actually going on. I felt isolated even while surrounded by kind and caring people.

This is the human situation: We often see others through our prior experiences and expectations. We are so mesmerized by these ghostly images that we don’t really encounter each other. Memory ghosts can be so dense and murky that we can’t see through them, forming a protective shell that makes us feel disconnected from life.

This is the human situation: We often see others through our prior experiences and expectations. We are so mesmerized by these ghostly images that we don’t really encounter each other. Memory ghosts can be so dense and murky that we can’t see through them, forming a protective shell that makes us feel disconnected from life.

Memory ghosts sometimes signal a deep hurt or disappointment that needs to be attended to and released. So we have to pay attention to the types of movies that cycle through our minds. If we learn to see them clearly without judgment or criticism and without getting caught up in them, they can serve a deeper purpose, becoming an inner resource that nourishes our aspiration and offers insight and emotional release.

Throughout this book, I’ll offer hints and techniques to guide you along, but in the end we learn how to do this deep inner work by doing it. If you stay with it, at some point you will begin to disidentify with your movies and experience an inner openness that allows you to remain receptive to life. Eventually, you’ll learn to recognize responses that sustain this openness. But first, you’ll have to see clearly those responses that close you down.

Caught In a Self-Centered Dream

We know so many things but we don’t know ourselves.

—Meister Eckhart

I’d like to share a story about a woman I’ll call Alice. Alice had a beautiful daughter that she was proud of. She was very involved in her daughter’s life, and she considered herself to be a good mother, but when her daughter went to college and had a psychotic break, everything changed. Alice felt responsible. This was the early seventies, a time when many people believed that mental illness was inherited from the mother. So now, in Alice’s mind, she was a bad mother. To escape her guilt, she began to drink heavily.

She went into therapy that lasted for several years, during which time she learned that her daughter’s schizophrenia had nothing to do with her. Alice became a mental health advocate, because she now felt that she was a good person with something meaningful to contribute.

Then Alice’s youngest son got kicked out of college for using drugs, and her husband left her for her best friend. Now Alice felt that she was a terrible mother, a terrible wife, and even a terrible human being.

Soon thereafter, her daughter with schizophrenia gave birth to an adorable baby that they parented together, and Alice became a happy, fulfilled mother and grandmother. A few years later, however, her daughter went off her meds, had paranoid delusions, and ran off with the child. Who did Alice think she was then?

Like Alice, many people wander through life experiencing a series of changing roles, like actors in a succession of movies. Who are we in the midst of all these roles? Are we our ideas? Are we our thoughts, our concerns, our movies? Or are we the extended feelings, the moods, the instinctual urges that underlie the movie-making world that we live in?

Meditation is about seeing the multiplicity of roles we identify with, and the way these roles continuously arise and vanish. If we hold them lightly, the roles remain transparent, allowing us to see and appreciate their ever-changing nature.

Meditation is about seeing the multiplicity of roles we identify with, and the way these roles continuously arise and vanish. If we hold them lightly, the roles remain transparent, allowing us to see and appreciate their ever-changing nature.

As Alice’s story shows, we identify with certain components of our experience, tie these components together, and call this string of events our self. This seems to be the nature of our movie-making mind. These mental movies have the capacity to either diminish or enrich our lives.

Buddha taught that what we experience as continuity arises from a continuous flow of activity, rather than a solid, unchanging self. Alice’s story points to the key to understanding the wisdom of this chapter.

KEY #1: Recognizing the self as a process frees us from a self-centered dream.

We begin to experience freedom from our habituated way of experiencing the world as we learn to see the self as a process rather than a solid being moving through time. For most of us, however, freedom from our fear-based way of thinking does not come easily.

In the thick of the forest is where you will find your freedom.

—Buddha

We never know when we’re going to find ourselves in the thick of the forest. For my friend Sydney, a long-time meditator, the discovery of freedom came through a major stroke that left her unable to speak. When I went to see her, she used a writing pad to communicate. Her hand shook uncontrollably as she wrote, “I’m okay. Learned not this face. Learned not this body.” When I looked at her, her eyes were suffused with loving acceptance.

Sydney found peace, even tranquility, after her stroke because she had sustained a regular meditation practice for many years. Even a practice of only twenty minutes a day can help you hold your movie-making response lightly.

To really penetrate the movies and follow them all the way in so as to see the patterns that produce them, however, requires more. That’s why we have Zen retreats that last from three days to a week or even longer.

A few years ago, during a long retreat, a student came to see me for a private meeting. She said, “I think it’s going well because my mind has gotten very quiet. But it’s kind of scary. Who will I be if I lose myself? How will I function in the world?” As she spoke she churned up more and more doubt until finally she exclaimed, “I think I should go home now.”

This frequently happens in Zen retreats. When you finally experience some stillness, these questions become relevant. How do you identify with non-being? There’s nothing there to identify with. It can be disconcerting at first. But it’s right here, in the thick of the forest, that we discover a wonderful freedom that our movie-making mind cannot touch.

I encouraged the retreat participant to stay with her anxiety and ride it out. She agreed to give it try. When she came to see me a couple of days later, her mood was quite different. She spoke of the stillness and peacefulness she was experiencing. “When the bell rang to end a meditation session, my body rose on its own. My body knows what to do.”

Whatever you experience in meditation becomes your teacher if you just stay with it. Even asthma can be your teacher, as my friend Eleanor discovered. Eleanor was planning a long retreat with Katagiri Roshi, then the guiding teacher of Minnesota Zen Meditation Center. She was worried about doing the retreat because she had to use an inhaler frequently. That meant she would have to use it during meditation, but she was clinging to her idea that she should not move during meditation.

Katagiri Roshi encouraged her to do the retreat. He counseled her to be with the stress in her throat if she could and to use her inhaler whenever she needed to. “Use the stress in your throat as the object of your meditation,” he said.

Eleanor began the retreat knowing that she could use her inhaler any time. But as the retreat went on, she was able to relax into the stress in her throat more and more. She stayed for the entire seven-day retreat. By the end, she noticed that her throat muscles had relaxed and her breath was not so shallow.

By being with it rather than trying to avoid or escape it, asthma became Eleanor’s thick of the forest. It became a place of freedom where before there was only limitation.

Being human can feel like being trapped—trapped in a body that demands and bullies, a mind that ridicules and spins out over every little thing, a dangerous and confounding world. But is it really that way? The next three chapters will take you into the darkest forest, to the very places where we feel most lost and most vulnerable. But you’ll have a guide and a flashlight. All you need to bring is an open mind and a willing heart. The last section of each chapter, Doing the Work, is where your eyes begin to adjust to the dark, and your own insight becomes your guide.

Core Meditation Practice for Calming and Centering

If you’re meditating at home, it’s important to designate a certain place for your practice. It can also help to create a bit of ritual that signals to your brain your intention to meditate. You might begin by closing the blinds or curtains, dimming the lights, lighting a candle, or perhaps burning a bit of incense. Take each step with your full attention. Feel the floor against your feet and the feel of the match or lighter as you light the candle; notice how the flame flares up and the smoke curls and spirals. When these tasks are performed with attentiveness, always in the same order, and with one-pointed focus, they become a calming and centering ritual. Your mind will start to settle down before you even begin the meditation.

During meditation, when your mind becomes distracted from your breath (and it will, over and over), try to notice the distraction and then return without comment or reactivity. When some emotional reactivity does bubble up, say frustration or irritation, focus on the bodily sensations of frustration or irritation rather than your thoughts. Stay with the sensations until they dissolve and then return to the object of focus. Don’t try to suppress your thoughts. The point is to become aware of your thought patterns by noticing the arising of a pattern without getting caught up in it. That’s why we stay focused on the breath, using it as an anchor so we can see our patterns without reinforcing them.

During meditation, when your mind becomes distracted from your breath (and it will, over and over), try to notice the distraction and then return without comment or reactivity. When some emotional reactivity does bubble up, say frustration or irritation, focus on the bodily sensations of frustration or irritation rather than your thoughts. Stay with the sensations until they dissolve and then return to the object of focus. Don’t try to suppress your thoughts.

Start by taking a few deep breaths and notice where in your body you feel your breath most prominently. It may be in your nostrils, or as your breath moves down your throat, or in the rise and fall of your chest or belly. Just rest your focus in that area and then allow your breath to return to its natural rhythm, without trying to control it. If your breath is shallow and quick, let it be shallow and quick; if it’s slow and deep, let it be slow and deep. Feel the openness that allows the breath to come and go on its own, without hindrance. Bring that same non-attached openness to whatever arises in your mind.

Allowing your breath, thoughts, emotions, and sensations to arise and then dissolve on their own is one of the most difficult things for a human being to do. The specific nature of the difficulty reveals something about our own patterns of reactivity. Is it difficult to let your breath be, without controlling or judging? Do you get agitated or angry when you catch your mind wandering off? You can start to free yourself from your inner control freak by simply observing the rhythm of your own breath without interfering and then extending that gentle attentiveness to your thoughts and emotions as they arise.

As we follow the natural rhythm of our breath, we begin to discover in an experiential way that our thoughts, sensations, and emotions come and go as naturally as the breath if we do not cling to them or try to avoid them. Of course emotions are more viscous and slow-moving than breath, but they come and go nevertheless, because this is the natural rhythm of life. It is only our fear that we’ll be overwhelmed by our emotions or do something stupid that makes us feel out of balance or out of sync with reality. Meditation gives us the opportunity to get to know our emotions in an intimate way so we’re comfortable with them. Even the strong emotions that we try so hard to avoid become fresh new avenues of insight and deepen our capacity for compassion.

Doing the Work

1. Think for a moment about a personal narrative—a mental movie—that you play over and over in your mind. As an antidote, imagine the unfolding of an opposite story. See if you can find a memory that affirms this new story line. Or you may bring to mind a memory that supports the old story line—and open yourself up to a new interpretation.

2. Recall a time when you found yourself in the thick of the forest. What did this experience teach you about yourself?

Related Books

$16.95 - Paperback

By: Norman Fischer & Bill Anelli & Natalie Goldberg & Katherine Thanas