Thupten Jinpa

Thupten Jinpa received his early education in the classical Tibetan system and holds a Lharam degree (the Tibetan equivalent to a doctorate in divinity) as well as a Ph.D. from Cambridge University, where he also worked as a research fellow at Girton College. He has been the principal English translator for the Dalai Lama since 1986. He is currently the president of the newly established Institute of Tibetan Classics dedicated to translating key Tibetan classics into contemporary languages. He lives in Montreal, Canada, with his wife and two young children.

Thupten Jinpa

-

Dzogchen$21.95- Paperback

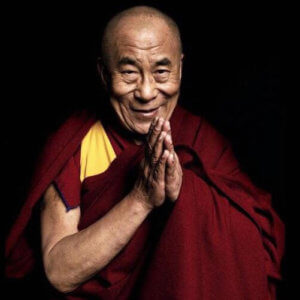

Dzogchen$21.95- PaperbackBy H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

By Nyoshul Khenpo

Translated by Thupten Jinpa

Translated by Richard Barron (Chokyi Nyima)

Edited by Patrick Gaffney -

Songs of Spiritual Experience$22.95- Paperback

Songs of Spiritual Experience$22.95- PaperbackTranslated by Jas Elsner

Translated by Thupten Jinpa

Foreword by H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama -

As Long as Space Endures$39.95- Paperback

As Long as Space Endures$39.95- PaperbackEdited by Edward A. Arnold

By Alexander Berzin

Foreword by Robert A. F. Thurman

By Giacomella Orofino

By Phillip Lesco

By Francesco Sferra

By Laura Harrington

By Gavin Kilty

By Miranda Shaw

By Glenn Wallis

By Vesna A. Wallace

By David B. Gray

By Urban Hammar

By Michael Sheehy

By Edward Henning

By Georgios T. Halkias

By David Reigle

By Thupten Jinpa

By Joe Loizzo

By Ivette Vargas

By William C. Bushell

By Sofia Stril-Rever

By Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim

By Geshe Drakpa Gelek

By Jhado Rinpoche -

The Union of Bliss and Emptiness$19.95- Paperback

The Union of Bliss and Emptiness$19.95- PaperbackBy H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Translated by Thupten Jinpa

- Buddhist Academic 1 item

- Buddhist Anthology 2item

- Buddhist Biography/Memoir 1 item

- Buddhist History 2item

- Buddhist Philosophy 1 item

- Dependent Origination 1 item

- Dalai Lamas 4item

- Dzogchen 1 item

- Gelug Tradition 3item

- Guru Yoga 1 item

- Jonang Tradition 1 item

- Kalachakra 1 item

- Nyingma Tradition 1 item

- Tantra 1 item

- Buddhist Poetry 1 item

GUIDES

Tsongkhapa: A Guide to His Life and Works

The Life of Tsongkhapa Lobsang Drakpa (1357-1419)

Tsongkhapa Lobzang Drakpa (1357–1419), was one of the most important figures in Tibet, historically and philosophically. As the founder of the Gelug school he made an enormous contribution to revitalizing Buddhism in Tibet. Regarded as an emanation of Manjushri--the bodhisattva of wisdom and discerning intelligence, Tsongkhapa was of keen intellect as well as experiential understanding of the Buddhist tradition. He undertook many long retreats during which he had profound visions out of which he wrote many of his celebrated treatises including Lam Rim Chenmo or The Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path. A prolific writer, he composed 210 treatises, compiled into 20 volumes wherein he emphasized the combined paths of Sutra and Tanta. In addition, he established the acclaimed Ganden monastery.

For a longer biography of Tsongkhapa read an excerpt from Geshe Sonam Rinchen's commentary on The Three Principal Aspects of the Path.

"Born in 1357 in Amdo, northeastern Tibet, and educated in central Tibet, Tsongkhapa led a life that exemplified the importance of study, critical reflection, and meditative practice. In an autobiographical poem he declared:

"First I sought wide and extensive learning,

Second I perceived all teachings as personal instructions,

Finally, I engaged in meditative practice day and night;

All these I dedicated to the flourishing of the Buddha’s teaching.By the end of his life, 600 years ago, Tsongkhapa was widely revered across Tibet. He had studied and corresponded with the most renowned teachers of his time, from all the major traditions, and had spent years in meditative retreat."

—From the Foreward by H. H. The Dalai Lama, Tsongkhapa: A Buddha in the Land of Snows, by Thupten Jinpa

The Definitive Biography of Tsongkhapa

Paperback | Ebook

$29.95 - Paperback

Marking the 600th anniversary of Tsongkhapa, in 2019 we published what is the most comprehensive, definitive biography of this great figure, written by Thupten Jinpa. The author is best known as the main translator for the Dalai Lama, but he is an author and scholar himself, having earned a Geshe degree. In the author’s words,

this new biography of Tsongkhapa…is aimed primarily at the contemporary reader. And it seeks to answer the following key questions for them: ‘Who was or is Tsongkhapa? What is he to Tibetan Buddhism? How did he come to assume the deified status he continues to enjoy for the dominant Geluk School of Tibetan Buddhism? What relevance, if any, do Tsongkhapa’s thought and legacy have for our contemporary thought and culture?

—Thupten Jinpa, from the Introduction to Tsongkhapa: A Buddha in the Land of Snows

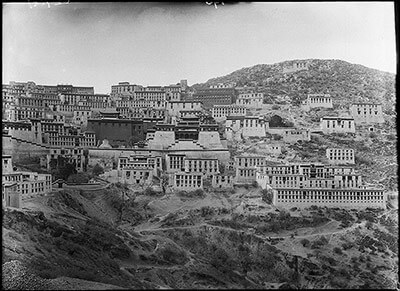

Ganden monastery, founded by Tsongkhapa, photographed in 1921 by Sir Charles Bell

Whoever sees or hears

Or contemplates these prayers,

May they never be discouraged

In seeking the bodhisattva’s amazing aspirations.

By praying with such expansive thought

Created from the power of pure intention,

May I achieve the perfection of prayers

And fulfill the wishes of all sentient beings.

Tsongkhapa's Lam Rim Chenmo, The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment

Tsongkhapa's main contribution to this genre is the famous Lamrim Chenmo or The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. It is also generally considered his most influential work, studied and practiced by tens of thousands today.

The background to this work is on one of Tsongkhapa’s own letters to a lama, included in Art Engle's The Inner Science of Buddhist Practice, where he describes it as building on Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment:

“It is clear that this instruction [introduced] by [Atisha] Dīpaṃkara Śrījnāna on the stages of the path to enlightenment . . . teaches [the meanings contained in] all the canonical scriptures, their commentaries, and related instruction by combining them into a single graded path. One can see that when taught by a capable teacher and put into practice by able listeners it brings order, not just to some minor instruction, but to the entire [body of] canonical scriptures. Therefore, I have not taught a wide variety of [other] instructions.”

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Vol. 1-3)

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Tib. Lam rim chen mo) is one of the brightest jewels in the world’s treasury of sacred literature. The author, Tsong-kha-pa, completed it in 1402, and it soon became one of the most renowned works of spiritual practice and philosophy in the world of Tibetan Buddhism. Because it condenses all the exoteric sūtra scriptures into a meditation manual that is easy to understand, scholars and practitioners rely on its authoritative presentation as a gateway that leads to a full understanding of the Buddha’s teachings.

Tsong-kha-pa took great pains to base his insights on classical Indian Buddhist literature, illustrating his points with classical citations as well as with sayings of the masters of the earlier Kadampa tradition. In this way the text demonstrates clearly how Tibetan Buddhism carefully preserved and developed the Indian Buddhist traditions.

Paperback| Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

(Volume 1)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This first of three volumes covers all the practices that are prerequisite for developing the spirit of enlightenment (bodhicitta).

Paperback| Ebook

$28.95 - Paperback

(Volume 2)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This second of three volumes covers the deeds of the bodhisattvas, as well as how to train in the six perfections.

Paperback| Ebook

$34.95 - Paperback

(Volume 3)

By Tsongkhapa

Edited by Joshua Cutler and Guy Newland, Translated by Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee

This third and final volume contains a presentation of the two most important topics in the work: meditative serenity (śamatha) and supramundane insight into the nature of reality (vipaśyanā).

Commentaries on Tsongkhapa's Great Treatise and other Lam Rim (Stages of the Path) texts

"The Great Treatise was written by Lama Tsong-kha-pa, a great scholar, a real holder of the Nalanda tradition. I think he is one of the very best Tibetan scholars. Although it is now widely available in Tibetan as well as English, you see that I brought with me today my own personal copy of this text. On March 17th, 1959, when I left Norbulingka that night, I brought this book with me. Since then I have used it ten or fifteen times to give teachings, all from this copy. So this is something very dear to me."

-H.H The Dalai Lama discussing his copy of the Great Treatise in From Here to Enlightenment

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

From Here to Enlightenment

An Introduction to Tsong-kha-pa's Classic Text The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment

By H.H. The Dalai Lama and translated by Guy Newland

When the Dalai Lama was forced into exile in 1959, he could take only a few items with him. Among these cherished belongings was his copy of Tsong-kha-pa’s classic text The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. This text distills all the essential points of Tibetan Buddhism, clearly unfolding the entire Buddhist path.

In 2008, celebrating the long-awaited completion of the English translation of the Great Treatise, the Dalai Lama gave a historic six-day teaching at Lehigh University to explain the meaning of the text and underscore its importance. It is the longest teaching he has ever given to Westerners on just one text—and the most comprehensive. From Here to Enlightenment makes the teachings from this momentous event available for a wider audience.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

Introduction to Emptiness

As Taught in Tsong-kha-pa's Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path

By Guy Newland

Readers are hard-pressed to find books that can help them understand the central concept in Mahayana Buddhism—the idea that ultimate reality is emptiness. In clear language, Introduction to Emptiness explains that emptiness is not a mystical sort of nothingness, but a specific truth that can and must be understood through calm and careful reflection. Newland's contemporary examples and vivid anecdotes will help readers understand this core concept as presented in one of the great classic texts of the Tibetan tradition, Tsong-kha-pa's Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment. This new edition includes quintessential points for each chapter.

Paperback | Ebook

$17.95 - Paperback

Refining Gold

Stages in Buddhist Contemplative Practice

By H.H. The Dalai Lama

In this extensive teaching, the Dalai Lama beautifully elucidates the meaning of the path to enlightenment through his own direct spiritual advice and personal reflections. Based on two very famous Tibetan text—Tsongkhapa's Song of the Stages on the Spiritual Path and the Third Dalai Lama's Essence of Refined Gold—this teaching presents in practical terms the essential instructions for the attainment of enlightenment. Its direct approach and lucid style make Refining Gold one of the most accessible introductions to Tibetan Buddhism ever published. His discourse draws out the meaning of the Third Dalai Lama’s famous Essence of Refined Gold as he speaks directly to the reader, offering advice, personal reflections, and scriptural commentary. He says in practical terms what the student must do to attain enlightenment.

Tsongkhapa's Three Principle Aspects of the Path

This is the shortest Lamrim text Tsongkhapa composed. Tsongkhapa wrote the fourteen stanzas of this classic distillation of all the paths of practice that lead to enlightenment. The three principal elements of the path referred to are: (1) renunciation, tied to the wish for freedom from cyclic existence; (2) the motivation to attain enlightenment for the benefit of others; (3) cultivating the correct view that realizes emptiness.

Paperback | eBook

$21.95 - Paperback

Three Principal Aspects of the Path

By Geshe Sonam Rinchen, edited and translated by Ruth Sonam

The wish for freedom, the altruistic intention, and the wisdom realizing emptiness constitute the essence of the Buddhist path. In this teaching, Geshe Sonam Rinchen explains, in clear and readily accessible terms, Je Tsongkhapa’s (1357–1419) famed presentation of these three essential topics.

The Three Principal Aspects is also included in Cutting Through Appearances: Practice and Theory of Tibetan Buddhism in which Geshe Sopa annotates the Fourth Panchen Lama’s instructions on how to practice this text in a meditation session.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama teaches on this text, and this is included as the chapter “The Path to Enlightenment” in Kindness, Clarity, and Insight.

Paperback | Ebook

$39.95 - Paperback

Paperback | Ebook

$16.95 - Paperback

Paperback | eBook

$29.95 - Paperback

Another work where Tsongkhapa’s Lamrim is featured is in Changing Minds: Contributions to the Study of Buddhism and Tibet in Honor of Jeffrey Hopkins. There are three chapters devoted to Tsongkhapa:

- Guy Newland’s Ask a Farmer: Ultimate Analysis and Conventional Existence in Tsongkhapa’s Lam Rim Chen Mo

- Daniel Cozort’s Cutting the Roots of Virtue: Tsongkhapa on the Results of Anger

- Elizabeth Napper’s Ethics as the Basis of a Tantric Tradition: Tsongkhapa and the Founding of the Gelugpa Order

Lotsawa House also includes a translation of these fourteen stanzas.

Tsongkhapa on Madhyamaka, The Middle Way School

Tsongkhapa is known for his distinct approach to the middle way philosophical system (madhyamaka) propounded by Indian masters Nāgārjuna (circa 200 CE) and Candrakīrti (circa 600 CE).

"I first went to India in 1972 on a dissertation research Fulbright fellow-ship, where although advised by the Fulbright Commission in New Delhi not to go to Dharmsala because of possible political complications, I went after a brief trip to Banaras. There I found that the Dalai Lama was about to begin a sixteen-day series of four- to six-hour lectures on Tsong-kha-pa Lo-sang-drak-pa’s Medium-Length Exposition of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment Practiced by Persons of Three Capacities. Despite my cynicism that a governmentally appointed reincarnation could possibly have much to offer, I slowly became fascinated first with the strength and speed of his articulation and then, much more so, with the touching meanings that were conveyed."

-Jeffrey Hopkins, from the Preface to Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom

Paperback | eBook

$44.95 - Paperback

Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom

By Jeffrey Hopkins

In fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Tibet there was great ferment about what makes enlightenment possible, since systems of self-liberation must show what factors pre-exist in the mind that allow for transformation into a state of freedom from suffering. This controversy about the nature of mind, which persists to the present day, raises many questions. This book first presents the final exposition of special insight by Tsong-kha-pa, the founder of the Ge-luk-pa order of Tibetan Buddhism, in his medium-length Exposition of the Stages of the Path as well as the sections on the object of negation and on the two truths in his Illumination of the Thought: Extensive Explanation of Chandrakirti's Supplement to Nagarjuna's "Treatise on the Middle." It then details the views of his predecessor Dol-po-pa Shay-rap Gyel-tsen, the seminal author of philosophical treatises of the Jo-nang-pa order, as found in his Mountain Doctrine, followed by an analysis of Tsong-kha-pa's reactions. By contrasting the two systems—Dol-po-pa's doctrine of other-emptiness and Tsong-kha-pa's doctrine of self-emptiness—both views emerge more clearly, contributing to a fuller picture of reality as viewed in Tibetan Buddhism. Tsong-kha-pa's Final Exposition of Wisdom brilliantly explicates ignorance and wisdom, explains the relationship between dependent-arising and emptiness, shows how to meditate on emptiness, and explains what it means to view phenomena as like illusions.

Paperback

$34.95 - Paperback

The Ornament of the Middle Way

A Study of the Madhyamaka Thought of Santaraksita

By James Blumenthal

The late James Blumenthal explores this important text by Shantarakshita and brings in Tsongkhapa’s text on this subject.

Shantarakshita's The Ornament of the Middle Way is among the most important Mahayana Buddhist philosophical treatises to emerge on the Indian subcontinent. In many respects, it represents the culmination of more than 1300 years of philosophical dialogue and inquiry since the time of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. Shantarakshita set forth the foundation of a syncretic approach to contemporary ideas by synthesizing the three major trends in Indian Buddhist thought at the time (the Madhyamaka thought of Nagarjuna, the Yogachara thought of Asanga, and the logical and epistemological thought of Dharmakirti) into one consistent and coherent system. Shantarakshitas's text is considered to be the quintessential exposition or root text of the school of Buddhist philosophical thought known in Tibet as Yogachara-Svatantrika-Madhyamaka. In addition to examining his ideas in their Indian context, this study examines the way Shantarakshita's ideas have been understood by and have been an influence on Tibetan Buddhist traditions. Specifically, Blumenthal examines the way scholars from the Geluk School of Tibetan Buddhism have interpreted, represented, and incorporated Santaraksita's ideas into their own philosophical project. This is the first book-length study of the Madyamaka thought of Shantarakshita in any Western language. It includes a new translation of Shantarakshita's treatise, extensive extracts from his autocommentary, and the first complete translation of the primary Geluk commentary on Shantarakshita's treatise.

"As a religious reformer, he has been likened to Luther by Western Buddhologists; but as a religious scholar he is regarded in his own culture as a genius whose statue more closely parallels that of Aquinas in Western Christianity. For Tsongkhapa created his own unique interpretation of Buddhist systematics and hermeneutics, in which he synthesized themes from all the Tibetan Buddhist traditions of his era. For these reasons he was praised by the Eight Karmapa as Tibet's chief exponent of ultimate truth, who revived the Buddha's doctrine at a time when the teachings of all four major Tibetan Buddhist lineages were in decline."

-B. Alan Wallace, from the Preface to Balancing the Mind

Paperback | eBook

$24.95 - Paperback

Balancing the Mind

A Tibetan Buddhist Approach to Refining Attention

By B. Alan Wallace

For centuries, Tibetan Buddhist contemplatives have directly explored consciousness through carefully honed and rigorous techniques of meditation. B. Alan Wallace explains the methods and experiences of Tibetan practitioners and compares these with investigations of consciousness by Western scientists and philosophers. Balancing the Mind includes a translation of the classic discussion of methods for developing exceptionally high degrees of attentional stability and clarity by fifteenth-century Tibetan contemplative Tsongkhapa.

Tsongkhapa and the Debate over the Two Truths

Tsongkhapa is famous—and in some circles controversial—for his presentation and positioning of the Prasangika view of Madhyamaka. Any discussion or debate of this subject invariably references Tsongkhapa.

Hardcover | eBook

$78.00 - Hardcover

The Center of a Sunlight Sky

Madhyamaka in the Kagyu Tradition

By Karl Brunnhölzl

This comprehensive work by Karl Brunnholzl explores all facets of Madhyamaka in the Kagyu tradition, but no analysis of Madhyamaka can leave out Tsongkhapa who appears throughout this work. There is a sixty-page section comparing the views of Tsongkhapa to those of Mikyo Dorje’s “whose writing, not only is a reaction to the position of Tsongkhapa and his followers but addresses most of the views on Madhyamaka that were current in Tibet at the time, including the controversial issue of ‘Shentong-Madhyamaka.’”

Paperback| eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

The Adornment of the Middle Way

Shantarakshita's Madhyamakalankara with Commentary by Jamgon Mipham

By Jamgon Mipham, translated by Padmakara Translation Group

For a different take on Shantarakshita's The Ornament of the Middle Way (same text, differently translated title) The Adornment of the Middle Way translated by the Padmakara Translation Group, gives a helpful introduction on the various interpretations. This longer passage offers a glimpse into some of the fault lines in the debate:

"The brilliance of Tsongkhapa’s teaching, his qualities as a leader, his emphasis on monastic discipline, and the purity of his example attracted an immense following. Admiration, however, was not unanimous, and his presentation of Madhyamaka in particular provoked a fierce backlash, mainly from the Sakya school, to which Tsongkhapa and his early disciples originally belonged. These critics included Tsongkhapa’s contemporaries Rongtön Shakya Gyaltsen (1367–1449) and Taktsang Lotsawa (1405–?), followed in the next two generations by Gorampa Sonam Senge (1429–1487), Serdog Panchen Shakya Chokden (1428–1509), and the eighth Karmapa, Mikyö Dorje (1505–1557). All of them rejected Tsongkhapa’s interpretation as inadequate, newfangled, and unsupported by tradition. Although they recognized certain differences between the Prasangika and Svatantrika approaches, they considered that Tsongkhapa had greatly exaggerated the divergence of view. They believed that the difference between the two subschools was largely a question of methodology and did not amount to a disagreement on ontological matters.

Not surprisingly, these objections provoked a counterattack, and they were vigorously refuted by Tsongkhapa’s disciples. In due course, however, the most effective means of silencing such criticisms came with the ideological proscriptions imposed at the beginning of the seventeenth century. These followed the military intervention of Gusri Khan, who put an end to the civil war in central Tibet, placed temporal authority in the hands of the Fifth Dalai Lama, and ensured the rise to political power of the Gelugpa school. Subsequently, the writings of all the most strident of Tsongkhapa’s critics ceased to be available and were almost lost. It was, for example, only at the beginning of the twentieth century that Gorampa’s works could be fully reassembled, whereas Shakya Chokden’s works, long thought to be irretrievably lost, were discovered only recently in Bhutan and published as late as 1975."

-from the Introduction to The Adornment of the Middle Way

The Wisdom Chapter

Jamgön Mipham's Commentary on the Ninth Chapter of The Way of the Bodhisattva

By Jamgon Mipham, translated by Padmakara Translation Group

This work on the Wisdom Chapter of Shantideva’s classic, written more than four centuries after Tsongkhapa, is a presentation of a different view than that expounded by Tsongkhapa. It is, in fact, a superb source for understanding the impact of his Madhyamaka presentation in a wider context, historically and philosophically. The extensive introduction gives a very complete and comprehensive account. In sum:

"In his treatment of the Gelugpa account, Mipham concurs in all important respects with Gorampa and the rest of Tsongkhapa’s earlier critics. Indeed, his critique is possibly even more effective in being expressed moderately and without vituperation. Nevertheless, he is careful never to attack Tsongkhapa personally. Given the fact that Mipham was a convinced upholder of the nonsectarian movement, there is no reason to doubt the sincerity of the humble and respectful manner with which he invariably refers to Tsongkhapa. No sarcasm is detectable in his words:

In the snowy land of Tibet, the great and venerable lord Tsongkhapa was unrivaled in his activities for the sake of the Buddha’s teaching. And with regard to his writings, which are clear and excellently composed, I do indeed feel the greatest respect and gratitude.

There is, however, a striking contrast between Mipham’s veneration of Tsongkhapa, on the one hand, and his penetrating critique of his view, on the other. Mipham’s assessment seems to oscillate between an approbation of some of Tsongkhapa’s positions, regarded as unproblematic expressions of a Svātantrika approach that Mipham valued, and a determination to demolish Tsongkhapa’s philosophical innovations and their pretended Prāsaṅgika affiliations. This discrepancy has led some scholars to accuse Mipham of inconsistency. Closer scrutiny suggests, however, that Mipham’s admittedly complex attitude to Tsongkhapa was in point of fact quite coherent."

-from the Introduction to The Wisdom Chapter

Tsongkhapa's Poetry and Songs of Realization

Paperback

$22.95 - Paperback

Thupten Jinpa’s collection of Tibetan poetry includes two poems by Tsongkhapa including Reflections on Emptiness, which is extracted from a larger work, the rTag tu ngu’i rtogs brjod—a poetic retelling of the story of the bodhisattva Sadāprarudita, who is associated with the 8,000 Verse Prajnamaramita Sutra and A Prayer for the Flourishing of Virtues.

Jinpa presents Tsongkhapa’s poetry first in terms of his mastery of composition and second, in terms of his mastery of the Buddhist path.

First, describing his master of composition, Jinpa writes:

Tsongkhapa’s famous long poem entitled ‘‘A Literary Gem of Poetry’’ uses a single vowel in every stanza throughout the entire length. This is the poem from which come the famous lines:

Good and evil are but states of the heart:

When the heart is pure, all things are pure;

When the heart is tainted, all things are tainted.

So all things depend on your heart.In the original Tibetan, this stanza uses only the vowel a. Of course, this kind of literary device can never be reproduced in a translation, whatever the virtuosity and command of the translator.

Second, describing his mastery of the Buddhist path Jinpa states:

To a contemporary reader, Tsongkhapa’s famous ‘‘Prayer for the Flourishing of Virtues’’ gives an insight into the deepest ideals of a dedicated Tibetan Buddhist practitioner; it presents a map of progressive development on the path. Beyond this, the mystic must utterly transform the very root of his identity and the perceptions that arise from it. From the ordinary patterns of action and reaction that make up our psyche and emotional life, the meditator must move toward a divine state of altered consciousness where all realities, including one’s own self, are manifested in their enlightened forms. In other words, the meditator must perfect all dimensions of his or her identity and experience, including rationality, emotion, intuition, and even sexuality. This, in Tibetan Buddhism, is the mystical realm of tantra.

Tsongkhapa and Tantra

A brief note. For those unfamiliar or only exposed through books, we strongly encourage readers to study tantra under the guidance of a qualified teacher. Book reading can only take you so far as the transmission of tantric teaching is about more than what can be put on paper.

This work is analogous to the tantra version of the Lamrim Chenmo, presenting tantra from the position of the sarma, ie., the 'new school,' or later transmission from India.

There are three books by Tsongkhapa and His Holiness the Dalai Lama that form a series focused on Tsongkhapa's Great Exposition of Secret Mantra. In this text, Tsongkhapa presents the differences between sutra and tantra and the main features of various systems of tantra. Each of the three books below begins with the Dalai Lama contextualizing and commenting on the points presented in Tsongkhapa's text, followed by a translation of the corresponding part of the text itself.

Paperback

$29.95 - Paperback

In Volume 1: Tantra in Tibet, the foundations of motivation, refuge, and the Hinayana and Mahayana paths are presented. He then gives an overview of tantra, the notion of Clear Light, the greatness of mantra, and initiation or empowerment.

This revised work describes the differences between the Great Vehicle and Lesser Vehicle streams in the sutra tradition, and between the sutra tradition and that of tantra generally. It includes highly practical and compassionate explanations from H.H. the Dalai Lama on tantra for spiritual development; the first part of the classic Great Exposition of Secret Mantra text; and a supplement by Jeffrey Hopkins on the difference between the Vehicles, emptiness, psychological transformation, and the purpose of the four tantras.

Paperback

$29.95 - Paperback

In Volume II: Deity Yoga, His Holiness discusses deity yoga at length with a particular focus on action and performance tantras (the first two categories of tantra as described in the sarma, or “new translation” schools).

This revised work describes the profound process of meditation in Action (kriya) and Performance (carya) Tantras. Invaluable for anyone who is practicing or is interested in Buddhist tantra, this volume includes a lucid exposition of the meditative techniques of deity yoga from H.H. the Dalai Lama; the second and third chapters of the classic Great Exposition of Secret Mantra text; and a supplement by Jeffrey Hopkins outlining the structure of Action Tantra practices as well as the need for the development of special yogic powers.

Paperback

$27.95 - Paperback

in Volume III: Yoga Tantra the Dalai Lama details the practice of the next level of tantra, yoga tantra. With a preliminary overview of the motivation, His Holiness explains this level, which focuses on internal yoga, which here means the union of deity yoga with the wisdom of realizing emptiness. He details the yoga, both that with and that without signs, and then briefly explains how gaining stability in these practices is the foundation for some other practices that lead to mundane and extraordinary “feats.”

This work opens with the Dalai Lama presenting the key features of Yoga Tantra then continues with the root text by Tsongkhapa. This is followed by an overview of the central practices by Khaydrub Je. Jeffrey Hopkins concludes the volume with an outline of the steps of Yoga Tantra practice, which is drawn from the Dalai Lama’s, Tsongkhapa’s, and Khaydrub Je’s explanations.

An explanation of the highest yoga tantra is not included in these works, but an excellent resource is Daniel Cozort's Highest Yoga Tantra.

Paperback

$39.95 - Paperback

The Six Yogas of Naropa

Tsongkhapa's Commentary

By Glenn H. Mullin

Tsongkhapa's commentary entitled A Book of Three Inspirations: A Treatise on the Stages of Training in the Profound Path of Naro's Six Dharmas is commonly referred to as The Three Inspirations. Anyone who has read more than a few books on Tibetan Buddhism will have encountered references to the Six Yogas of Naropa, a preeminent yogic technology system. The six practices—inner heat, illusory body, clear light, consciousness transference, forceful projection, and bardo yoga—gradually came to pervade thousands of monasteries, nunneries, and hermitages throughout Central Asia over the past five and a half centuries.

Paperback

$27.95 - Paperback

The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa

By Glenn H. Mullin

Another text that is included in Tsongkhapa’s collected works is the short Practice Manual on the Six Yogas. This is included in the wider collection of texts on this practice titled The Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa. Also included in this book are works by Tilopa, Naropa, Je Sherab Gyatso, and the First Panchen Lama.

From the Six Yogas of Naropa:

"Tsongkhapa's treatise on this system of tantric practice ... became the standard guide to the Naropa tradition at Ganden Monastery, the seat he founded near Lhasa in 1409. Ganden was to become the motherhouse of the Gelukpa school, and thus the symbolic head of the network of thousands of Gelukpa monasteries that sprang up over the succeeding centuries across Central Asia, from Siberia to northern India. A Book of Three Inspirations has served as the fundamental guide to Naropa's Six Yogas for the tens of thousands of Gelukpa monks, nuns, and lay practitioners throughout that vast area who were interested in pursuing the Naropa tradition as a personal tantric study. It has performed that function for almost six centuries now.

Tsongkhapa the Great's A Book of Three Inspirations has for centuries been regarded as special among the many. The text occupies a unique place in Tibetan tantric literature, for it in turn came to serve as the basis of hundreds of later treatments. His observations on various dimensions and implications of the Six Yogas became a launching pad for hundreds of later yogic writers, opening up new horizons on the practice and philosophy of the system. In particular, his work is treasured for its panoramic view of the Six Yogas, discussing each of the topics in relation to the bigger picture of tantric Buddhism, tracing each of the yogic practices to its source in an original tantra spoken by the Buddha, and presenting each within the context of the whole. His treatise is especially revered for the manner in which it discusses the first of the Six Yogas, that of the 'inner heat.' As His Holiness the present Dalai Lama put it at a public reading of and discourse upon the text in Dharamsala, India, in 1991, 'the work is regarded by Tibetans as tummo gyi gyalpo, the king of treatments on the inner heat yoga.' Few other Tibetan treatises match it in this respect."

Paperback | eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

This work has three main sections: an overview of Mahamudra, the First Panchen’s text The Main Road of the Triumphant Ones, and a commentary by the Dalai Lama. The author contextualizes the selection saying that the tradition of Mahamudra in the Gelug tradition comes through Tsongkhapa.

Other Notable Works Related to Tsongkhapa

Paperback | eBook

$39.95 - Paperback

Tibetan Literature

Studies in Genre

Edited by Jose Cabezon and Roger R. Jackson

Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre is a collection by leading Tibetologists. The immensity of Tibet's literary heritage, unsurprisingly, is filled with references to Tsongkhapa across a wide range of subjects. Just a sampling of them include: the establishment of the Gelug order; the monastic curriculum; debate manuals; establishment of Ganden; a comparison with Milarepa; the controversies about his views; a classification of his texts; and a lot more.

Paperback | eBook

$29.95 - Paperback

Mind in Tibetan Buddhism

By Lati Rinpoche, Edited and translated by Elizabeth Napper

Mind in Tibetan Buddhism is an oral commentary on Geshe Jampel Sampel's Presentation of Awareness and Knowledge Composite of All the Important Points, Opener of the Eye of New Intelligence. This topic, lorig in Tibetan, was not one on which Tsongkhapa wrote a dedicated text, but he does include it in an introduction to Dharmakirti’s Seven Treatises and one of his sections includes a brief presentation on lorig. Tsongkhapa is brought up throughout this book.

Tsongkhapa is also referenced in about 60 articles on shambhala.com, mostly from the Snow Lion newsletter archive.

Additional Resources

More can be found on Atisha's life on Treasury of Lives

Buddhist Poetry - A Reader Guide

A Reader Guide

Jump to sections on this page:

Recent Releases | Chan and Zen Poetry | Indian Poetry | Tibetan Poetry | Southeast Asian Poetry | Contemporary Buddhist Poetry

Recent Releases

Until Nirvana's Time: Buddhist Songs from Cambodia

By Trent Walker

Until Nirvana’s Time presents forty-five Dharma songs, whose soaring melodies have inspired Cambodian Buddhist communities for generations. Whether recited in daily prayers or all-night rituals, these poems speak to our deepest concerns—how to die, how to grieve, and how to repay the ones we love.

Introduced, translated, and contextualized by scholar and vocalist Trent Walker, this is the first collection of traditional Cambodian Buddhist literature available in English. Many of the poems have been transcribed from old cassette tapes or fragile bark-paper manuscripts that have never before been printed. A link to recordings of selected songs in English and Khmer accompanies the book.

Click here to listen to songs from the book, performed by Trent Walker.

Chan and Zen Poetry

The Poetry of Zen, edited by Sam Hamill & J.P. Seaton

Here, poet-translators Sam Hamill and J.P. Seaton offer up a rich sampling of poems from the Chinese and Japanese Zen traditions, spanning centuries of poets, from Lao Tzu to Kobayashi Issa. While a few of the poets included were not Zen practitioners, their poems nonetheless illustrate a strong Zen influence. Hamill and Seaton open the anthology with an overview of the Zen poetic tradition, and provide historical, philosophical, and biographical context to the works throughout, showing readers how poetry “is one of the many paths to enlightenment” (7). With a compact trim size, this collection makes a wonderful travel companion.

Poetry from Chinese Chan Masters

By Indara (因陀羅) (Yintuoluo) (Emuseum) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The Poetry of Enlightenment: Poems by Ancient Chan Masters, by Chan Master Sheng Yen

Look inside the minds of enlightened masters with this collection of Ch’an teaching poems. Chan Master Sheng Yen offers commentary on ten poems by ancient Chinese Ch’an masters, selected both for their simplicity of language and depth of meaning. Written by Ch’an practitioners post-enlightenment, these poems touch on the experience of Ch’an, how to practice, cultivating the right attitude, and obstacles to avoid, as well as offering a glimpse into the state of mind of enlightenment.

The Complete Cold Mountain: Poems of the Legendary Hermit Hanshan, translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi & Peter Levitt

Capturing readers with its insightful, light, humorous, and often rebellious spirit, Hanshan’s Cold Mountain poems have long been enjoyed by Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. This new translation of these centuries-old writings by Kaz Tanahashi and Peter Levitt presents readers not only the full body of poems in its entirety, but also provides a wealth of insight into the poets behind the poems, full Chinese text of the poems, historical context, and the Buddhist elements present throughout the collection. The translators’ deep appreciation for Hanshan shines through the collection. Translator Peter Levitt notes in the introduction, “Because of the compassionate discernment, profound tranquility, unexpected insight, and the occasional outrageous humor of his poetry, Kaz Tanahashi and I have gratefully considered Hanshan one of life’s treasured companions for fifty years. As a result of the kinship we feel with him, we gathered together, translated, and now offer readers the most complete version of the poet’s work to date in the English language” (2).

Poetry from Japanese Zen Masters

The Poetry of Ryokan

Widely admired both for his character and poetry, Ryokan remains one of the key poets of the Zen tradition. Though written in eighteenth century Japan, Ryokan’s poems seem to transcend time and space, with reflections on the human experience that are as relevant to today’s readers as they were centuries ago.

“Who says my poems are poems?

My poems are not poems.

When you know that my poems are not poems,

Then we can speak of poetry!”

*Image by Ryōkan (English: Replica before 1970) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

$18.95 - Paperback

Dewdrops on a Lotus Leaf: Zen Poems of Ryokan, translated & edited by John Stevens

Providing brief biographical context, John Stevens introduces us to the world and work of Ryokan. The collection demonstrates the spirit of Ryokan’s Zen outlook, with poems covering the full spectrum of the human experience and focusing on “things deep inside the heart.” Throughout the text are ink paintings by Koshi no Sengai, a devotee of Ryokan, many of which include calligraphy of Ryokan’s verses.

$19.95 - Paperback

One Robe, One Bowl: The Zen Poetry of Ryokan, translated & introduced by John Stevens

In comparison to Dewdrops, this collection offers a more detailed introduction to the life of Ryokan and his relationship to Zen Buddhism. Ryokan was not married to one poetic style, and thus this collection is broken up into classical Chinese style poems, and Japanese waka and haiku, organized by season.

$18.95 - Paperback

Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan, translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi

For readers who want to take a really deep dive into Ryokan, this is the collection to read. Not only does Tanahashi present Ryokan’s poetry (organized chronologically), but he also offers selections of Ryokan’s calligraphy, maps of relevant sites for readers’ reference, a detailed biographical introduction, notes on individual poems, an analysis of Ryokan’s poetic forms, and a collection of anecdotes about the beloved Zen poet.

The Poetry of Saigō

Saigyō, the Buddhist name of Fujiwara no Norikiyo (1118–1190), is one of Japan’s most famous and beloved poets. He was a recluse monk who spent much of his life wandering and seeking after the Buddhist way. Combining his love of poetry with his spiritual evolution, he produced beautiful, lyrical lines infused with a Buddhist perception of the world.

This world—

strug jewels

of dew

on the frail thread

a spider spins.

Gazing at the Moon: Buddhist Poems of Solitude, translated by Meredith McKinney, presents over one hundred of Saigyō’s tanka—traditional 31-syllable poems—newly rendered into English by renowned translator Meredith McKinney. This selection of poems conveys Saigyō’s story of Buddhist awakening, reclusion, seeking, enlightenment, and death, embodying the Japanese aesthetic ideal of mono no aware—to be moved by sorrow in witnessing the ephemeral world.

Check out the interview with Meredith McKinney on the Books on Asia Podcast!

Indian Buddhist Poetry

Songs of the Sons and Daughters of Buddha: Enlightenment Poems from the Theragatha and Therigatha, translated by Andrew Schelling and Anne Waldman

More than two thousand years ago, the earliest disciples of the Buddha put into verse their experiences on the spiritual journey—from their daily struggles to their spiritual realizations. Over time the verses were collected to form the Theragatha and Therigatha, the “Verses of Elder Monks” and “Verses of Elder Nuns” respectively. Renowned poets Andrew Schelling and Anne Waldman have translated the most poignant poems in these collections, bringing forth their visceral, immediate qualities.

Tibetan Buddhist Poetry

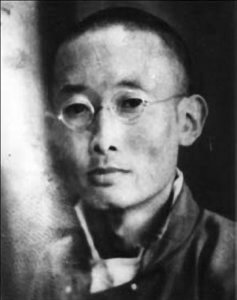

Gendun Chopel: Tibet’s Modern Visionary, by Donald S. Lopez Jr.

The debut title in Shambhala’s Lives of the Masters series, Gendun Chopel offers an in-depth look at the life and writings of the Tibetan Buddhist visionary, by scholar Donald Lopez. While much of this book is a biographical exploration of Gendun Chopel, Lopez also provides a wealth of Gendun Chopel’s writings, believing that “one learns a great deal about an author by actually reading what they wrote” (x). More than a Buddhist visionary, Gendun Chopel is considered one of Tibet’s greatest poets of the twentieth century, and thus included among these writings is a significant selection of poetry. As a student and writer of poetry throughout his life, he mastered many poetic forms, and often composed poems spontaneously.

The relatives and servants we meet are but guests on market day.

The rise of power, wealth, and arrogance are pleasures in a dream.

Happiness alternates with sorrow, summer changes to winter.

Thinking of this, a song spontaneously came to me.

$39.95 - Paperback

The Rain of Wisdom: The Essence of the Ocean of True Meaning, translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee

Translated under the direction of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, this collection offers more than one hundred vajra dohas of the Tibetan Kagyu lineage, by more than thirty lineage holders, including Tilopa, Milarepa, and the Sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa. Contained in these songs are teachings on karma, bodhicitta, devotion, and the Buddhist path. Trungpa Rinpoche writes in his Foreword, “these songs should be regarded as the best of the butter which has been churned from the ocean of milk of the Buddha’s teachings” (xiii).

$39.95 - Paperback

Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre

Renowned scholar Roger Jackson takes on the subject in the chapter ‘Poetry in Tibet: Glu, mGur, sNyan ngag and “Songs of Experience”. He explores Tibetan poetry from its earliest forms to the present including Trungpa Rinpoche and Allen Ginsberg.

The rise of power, wealth, and arrogance are pleasures in a dream.

Happiness alternates with sorrow, summer changes to winter.

Thinking of this, a song spontaneously came to me.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye’s ten volume Treasury of Knowledge includes the volume Indo-Tibetan Classical Learning & Buddhist Phenomenology (Book Six, Parts One & Two). Chapter eight catalogues the elements and components of Tibetan poetry including the types of composition (metrical, prose, and a mix of the two) as well as poetic ornaments.

Songs of Spiritual Experience: Tibetan Buddhist Poems of Insight and Awakening, selected & translated by Thupten Jinpa & Jas Elsner

Published in English for the first time, this collection of fifty-two poems by realized masters, from classic to contemporary, represents the full range of Tibetan Buddhist lineage traditions. Organized thematically, these songs address impermanence, guru devotion, emptiness, and other key themes of Tibetan Buddhism. Also included are a detailed glossary and exploration of the Tibetan tradition of nyamgur (“experiential songs”), offering a comprehensive look at poetry’s role within Tibetan Buddhism. A foreword for the collection is provided by His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

The introduction forms one of the best introductions to Tibetan poetry available. Here is a taste:

"Many of the greatest Tibetan poems demand of the reader an attentiveness to a complex line of thought and philosophical reasoning, albeit in the heightened forms of verse combined with the inspiration of imagery. For the poet, the ideal reader is one whose reading of the poem becomes itself an act of meditation, penetrating the depths of human experience with an insight tempered by sensitivity.

Listen to Thubten Jinpa discuss the Songs of Spiritual Experience

Other Media on Tibetan Buddhist Poetry

Watch this episode from the Tsadra Foundation’s Translation and Transmission conference in 2017 with leading scholars of Tibetan poetry.

Poems of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

While Trungpa Rinpoche was a Tibetan, his poetry is unique and has therefore been included in the contemporary Buddhist poetry section.

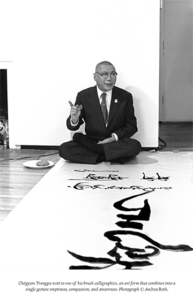

When Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche arrived in the United States, he asked, “Where are your poets? Take me to your poets!” Not only was Trungpa Rinpoche a spiritual teacher, but he was also an avid poet and dharma artist. Below, we describe the differences between our multiple collections of his work:

$19.95 - Paperback

Timely Rain: Selected Poetry of Chogyam Trungpa

Timely Rain is a collection of new and previously published poems, edited and curated by David I. Rome. While First Thought Best Thought presents poems in roughly chronological order, this collection is organized thematically, with each thematic section in chronological order. This allows readers to more easily navigate the poems, while also witnessing the evolution of Trungpa’s expressiveness and state of mind. Editor David Rome reflects in his Afterword that “poetry is also a refuge for Trungpa, perhaps the only place where he is able to step out of all the roles and self-inventions and speak truthfully from—and to—his own heart” (193). Themes contained herein include loneliness, samsara and nirvana, love, and sacred songs.

$16.95 - Paperback

Mudra is a selection of spontaneous, celebratory poems of devotion written by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche between 1959 and 1971. Trungpa opens his collection with two translations of Jigme Lingpa and Patrul Rinpoche, explaining that “they are the vajra statement which frees the people of the dark ages from the three lords of materialism and their warfare.” Also included are ten traditional Zen oxherding pictures along with Trungpa’s unique commentary.

$24.95 - Paperback

First Thought Best Thought: 108 Poems

Dictated (Trungpa composed poems verbally to a scribe) around the time of his arrival in the United States, this collection of poems, with an introduction by Allen Ginsberg, encapsulates Trungpa’s creative energy. His vision of joining East and West shines through each poem, combining classical Tibetan poetic influences with a modern American poetic style. As the collection progresses chronologically, readers witness Trungpa’s increasing familiarity and comfort with American culture. The collection’s title pays homage to William Blake’s “First thought is best in Art, second in other matters,” while also invoking the notion of beginner’s mind. As Ginsberg writes in his introduction, here is an “amazing chance to see his thought process step by step, link by link, cutting through solidifications of opinions & fixations” (xv).

Buddhist Songs and Poetry from Southeast Asia

Until Nirvana's Time: Buddhist Songs from Cambodia

By Trent Walker

Until Nirvana’s Time presents forty-five Dharma songs, whose soaring melodies have inspired Cambodian Buddhist communities for generations. Whether recited in daily prayers or all-night rituals, these poems speak to our deepest concerns—how to die, how to grieve, and how to repay the ones we love.

Introduced, translated, and contextualized by scholar and vocalist Trent Walker, this is the first collection of traditional Cambodian Buddhist literature available in English. Many of the poems have been transcribed from old cassette tapes or fragile bark-paper manuscripts that have never before been printed. A link to recordings of selected songs in English and Khmer accompanies the book.

Contemporary Buddhist Poetry

The First Free Women: Original Poems Inspired by the Early Buddhist Nuns, by Matty Weingast

Composed around the Buddha’s lifetime, the original Therigatha (“Verses of the Elder Nuns”) contains the poems of the first Buddhist women: princesses and courtesans, tired wives of arranged marriages and the desperately in love, those born into limitless wealth and those born with nothing at all. The authors of the Therigatha were women from every kind of background, but they all shared a deep-seated desire for awakening and liberation.

In The First Free Women, Matty Weingast has reimagined this ancient collection and created an original work that takes his experience of the essence of each poem and brings forth in his own words the struggles and doubts, as well as the strength, perseverance, and profound compassion, embodied by these courageous women.

Beneath a Single Moon: Buddhism in Contemporary American Poetry, edited by Kent Johnson & Craig Paulenich

For readers who prefer a more modern aesthetic, Beneath a Single Moon is a delightful read. This anthology features more than 250 poems by forty-five contemporary American poets, supplemented with essays exploring spiritual poetic practice. Among those included in this collection are John Cage, Diane di Prima, Norman Fischer, Allen Ginsberg, Susan Griffin, Anne Waldman, Philip Whalen, and Gary Snyder, who also provides the book’s introduction. Offering a refreshing look at spiritual poetry, the editors explain that “the variousness of the work [stands] very much at odds with the fairly common notion of American ‘Zen’ poetry as a literary remnant of the sixties, with derivative, and generally identifiable ‘Eastern’ criteria. It [is] even more intimately at odds, perhaps, with the well-diffused perception—at least in the West—of Buddhism as collectivizing and inimical to individual spirit” (xv-xvi).

After Ikkyu & Other Poems, by Jim Harrison

Those who find spiritual poetry can become too rigid or serious will find this to be a refreshing departure from the norm. These raw and often pithy poems by novelist Jim Harrison draw inspiration from his many years of Zen practice, and in perfect Zen spirit, they reveal a poet and practitioner who does not take himself too seriously. In his introduction Harrison explains, “It doesn’t really matter if these poems are thought of as slightly soiled dharma gates or just plain poems. They’ll live or die by their own specific density, flowers for the void” (ix).

Listen to a sample from Jim Harrison's original reading of After Ikkyu. Audiobook available on Audible and Apple.

Kurtis Schaeffer, Lives of the Masters series editor, introduces the series with this note:

"Buddhist traditions are heir to some of the most creative thinkers in world history. The Lives of the Masters series offers lively and reliable introductions to the lives, works, and legacies of key Buddhist teachers, philosophers, contemplatives, and writers. Each volume in the Lives series tells the story of an innovator who embodied the ideals of Buddhism, crafted a dynamic living tradition during his or her lifetime, and bequeathed a vibrant legacy of knowledge and practice to future generations.

Lives books rely on primary sources in the original languages to describe the extraordinary achievements of Buddhist thinkers and illuminate these achievements by vividly setting them within their historical contexts. Each volume offers a concise yet comprehensive summary of the master’s life and an account of how they came to hold a central place in Buddhist traditions. Each contribution also contains a broad selection of the master’s writings.

This series makes it possible for all readers to imagine Buddhist masters as deeply creative and inspired people whose work was animated by the rich complexity of their time and place and how these inspiring figures continue to engage our quest for knowledge and understanding today."

Related Titles

About the Books

Tsongkhapa: A Buddha in the Land of Snows

By Thubten Jinpa

H. H. The Dalai Lama introduces this monumental and definitive biography authored by his long-time translator Thubten Jinpa, and released 600 years following Tsongkhapa's parinirvana:

"An important part of Tsongkhapa’s legacy is the emphasis he placed on critical analysis as essential to the attainment of enlightenment. He revitalized the approach, typical of the Nalanda tradition, that takes reasoned philosophical scrutiny as essential to understanding the nature of reality. . . .

Tsongkhapa had a far-reaching impact on Tibetan tradition. In terms of the three higher trainings in ethics, concentration, and wisdom, he wrote, “Those who wish to discipline others have first to discipline themselves.” His strict adherence to the culture and practice of vinaya, or monastic discipline, set a widely admired standard. His thorough and illuminating writings about Madhyamaka philosophy profoundly enriched Tibetan understanding of Nāgārjuna’s school of thought, stimulating critical thinking about the deeper implications of the view of emptiness. Moreover, his systematic exploration of Buddhist tantra, especially the highest yoga systems of Guhyasamāja and Cakrasaṃvara, has ensured not only that their practice has flourished but also that they have been more clearly understood."

See more about Tsongkhapa in our Reader's Guide to his life and works.

Here is Thubten Jinpa sharing his experience composing this biography:

Atiśa Dīpaṃkara: Illuminator of the Awakened Mind

By James B. Apple

Atiśa perhaps had the greatest impact on Buddhism in Tibet of all the Indian masters who visited there. A founder of the Kadam school, the origin of the Geluk tradition of the Dalai Lamas, Atiśa was a brilliant synthesizer whose contributions to Madhyamaka, Tantra, Mind Training (lojong), and the lamrim tradition have continued to be fundamental for practitioners and scholars of Tantra and the Mahāyāna.

Enjoy an excerpt from the preface to the book:

"Atiśa’s life and teachings are a Tibetan story, and what an amazing story it is. Atiśa’s life is guided by dreams, visions, and predictions from buddhas and bodhisattvas, including the savioress Tārā. In the story of Atiśa’s life, we enter a world of gold, sailing ships, palm-leaf manuscripts, and mantras, rather than credit cards, automobiles, social media, and cell phones. The story involves transactions in over two million dollars’ worth of gold and travels throughout maritime Buddhist Asia. The Tibetans have faithfully preserved what is known of Atiśa Dīpaṃkaraśrījñāna, the vicissitudes of his life, the struggles in his travels, and the spirit and meaning of his teachings."

Gendun Chopel: Tibet's Modern Visionary

By Donald S. Lopez Jr.

Artist, poet, iconoclast, philosopher, adventurer, master of the arts of love, tantric yogin, Buddhist saint, world traveler—these are but a few of the descriptions of one of Tibet's most famous modern visionaries, now presented in a single, definitive volume. Having written six books on Gendun Chopel, Donald Lopez takes the culmination of his intimate study and six published works on this figure to present in a comprehensive way his achievements, legacy, and journey—from his recognition as a tulku, to his travels throughout Tibet, India, and Sri Lanka, to his controversial imprisonment in Lhasa and death following the communist invasion of Tibet.

In the introduction Donald Lopez Jr. presents Chopel alongside the politically charged atmosphere that shaped the life, travels, and writing of Tibet's modern visionary,

"Indeed, unlike other important figures in Tibetan history, he was a man who made his name abroad, his life beginning and ending with the two most consequential foreign invasions in Tibetan history. He was born in August 1903, four months before British troops, under the command of Colonel Francis Younghusband, crossed the border into Tibet. He died in October 1951. On September 9, he was lifted from his deathbed to watch the troops of the People’s Liberation Army march into Lhasa.

. . . Near the end of his life, one of the few disciples who remained loyal after he was released from prison asked him, in the traditional Tibetan way, to compose his autobiography. Rather than do so with a lengthy work characteristic of the genre, he responded spontaneously, with a four-line poem:

A virtuous family, the lineage of monks, the way of a layman,

A time of abundance, a time of poverty,

The best of monks, the worst of laymen,

My body has changed so much in one lifetime."

The most wide-ranging work available on this extraordinary figure, this inaugural book of the Lives of the Masters series is an instant classic.

Tibetan Language Reader's Guide

Interested in learning Tibetan or deepening your existing Tibetan language skills? Below is a guide to help you choose the right resources for your needs. We offer two tracks: one for those who plan on traveling or spending a longer period of time in India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, and Tibet; and another for those who are focused on classical written Tibetan for academic or practice purposes.

Reading or Translating Classical Tibetan

The following materials are geared for those wanting in-depth study of the written language of Tibet, including the classical and literary. These were all designed to work together and complement each other, though can be used stand-alone as well. For spoken/colloquial Tibetan, skip to that section below.

Translating Buddhism from Tibetan

This book is the foundation for the books that follow. It's a complete textbook on classical Tibetan suitable for beginning or intermediate students. Based on the system developed by Jeffrey Hopkins at the University of Virginia, it presents—in lessons with drills and reading exercises—a practical introduction to Tibetan grammar, syntax, and technical vocabulary used in Buddhist works on philosophy and meditation. A well-designed learning system, it serves as an introduction to reading and translating Tibetan as well as to Buddhist philosophy and meditation. Each chapter contains a vocabulary of helpful Buddhist terms. Students with prior experience will find that the seven appendices—which review the rules of pronunciation, grammar, and syntax—are an indispensable reference.

How to Read Classical Tibetan, Volume One

Craig Preston, the author, recommends that people study Translating Buddhism from Tibetan as a preliminary to using this book. This is a complete language course built around the exposition of a famous Tibetan text, Summary of the General Path to Buddhahood, written at the beginning of the fifteenth century. All the language tools you need to work at your own pace are here in one place. You won't need a dictionary because all the words and particles are translated and explained in each occurrence, and there is a complete glossary at the end of the book. Every sentence is diagrammed and completely explained so that you can easily see how the words and particles are arranged to convey meaning. Because everything is explained in every sentence, you will learn to recognize the recurrent patterns, which makes the transition from learning words to reading sentences easier than it would be otherwise. As you study How to Read Classical Tibetan, you will learn to recognize the syntactic relationships you encounter, understand the meaning signified, and translate that meaning correctly into English.

How to Read Classical Tibetan, Volume Two

A follow-up to Volume One, this book assumes the reader is familiar with both the previous volume and Translating Buddhism from Tibetan.

Learning Classical Tibetan: A Reader for Translating Buddhist Texts

Designed for both classroom use and independent study, Learning Classical Tibetan is a modern and accessible reader for studying traditional Buddhist texts. Unlike other readers of Classical Tibetan, this is a comprehensive manual for navigating Tibetan Buddhist literature drawing on a monastic curriculum. Utilizing the most up-to-date teaching methods and tools for Tibetan language training, students learn to navigate the grammar, vocabulary, syntax, and style of Classical Tibetan while also engaging the content of Buddhist philosophical works.

Chapters consist of a contextual introduction to each reading, a Tibetan text marked with references to annotations that provide progressive explanations of grammar, cultural notes on vocabulary, translation hints, notes on the Sanskrit origins of Tibetan expressions and grammatical structures, as well as a literal translation of the text. The reader also includes study plans for classroom use, discussion of dictionaries and other helpful resources, a glossary of English grammatical and linguistic terms, and much more.

This reader can be used in conjunction with Paul Hackett’s expanded edition of his well-known Tibetan Verb Lexicon. Using a clear and approachable style, Hackett provides a practical and complete manual that will surely benefit all students of Classical Tibetan.

A Tibetan Verb Lexicon

This is the second and much-expanded edition of this essential resource for those studying or translating Tibetan. edition . With over 4,500 entries of the most frequently used Tibetan verbs, this new edition of Hackett’s highly acclaimed Tibetan Verb Lexicon is an incomparable lexical resource. This comprehensive verb dictionary includes various verb forms, verbal collocations, auxiliary constructions together with grammatical information, Sanskrit equivalents, and example sentences, making it a vital tool for any translator, writer, or scholar who intends to maximize the quality of their work related to the Tibetan language.

Much more than a mere translation of existing works, this lexicon was compiled employing statistical techniques and data and draws on sources spanning the 1,200 years of Tibet's classical literature, covering all major lineages. The 4,500 root verb forms and phrasal verb subentries incorporates a wide range of information not previously available in dictionary form. The individual entries are in Tibetan script and contain English meanings, Sanskrit equivalents, complete sentences drawn from the corpus of Tibetan classical literature, and related sentence structure information. An extensive introduction to contemporary linguistic theory as applied to Tibetan verbs provides the theoretical underpinnings of the lexicon. Paul Hackett, the author, strongly encourages readers to become familiar with Translating Buddhism from Tibetan before approaching this book.

Spoken and Written Modern Tibetan

Below you will see our resources if you with to speak and read modern, colloquial Tibetan.

Learning Practical Tibetan

This book, for the casual traveler and aspiring student, offers a great overview, packed with practical examples for the casual student. It gives the basics of grammar and phonetics and offers practical sample dialogues. And it is small enough that you could easily take it with you on your adventure! It starts off with some basic grammar and vocabulary and then moves into dialogues for eating, shopping, visiting monasteries, transportation, and more.

Manual of Standard Tibetan

In this comprehensive treatment of modern Tibetan, you'll learn about the everyday speech of Lhasa as it is currently used in Tibet and in the Tibetan diaspora. It not only places the language in its natural context but also highlights key aspects of Tibetan civilization and Vajrayana Buddhism. The manual, which consists of forty-one lessons, includes many drawings and photographs as well as two political and linguistic maps of Tibet. You'll find the appendices especially helpful as they outline the differences between written literary and spoken Tibetan; detail pronunciation; and explain the use of honorific words, compound terms, and transfers from other languages. Two CDs provide an essential aural complement to the manual, making it a very practical guide for more serious students.

Fluent Tibetan

This book is a fully comprehensive course in spoken Tibetan which has MP3 files to support a real immersion experience. The most systematic and extensive course system now available for spoken Tibetan, Fluent Tibetan was developed by language experts working in conjunction with indigenous speakers at the University of Virginia. Based on government-approved courses for diplomats needing to learn a language quickly, the method acquaints students with the sounds and patterns of Tibetan speech through repetitive interactive drills, enabling the quick mastery of increasingly complex structures and thereby promoting rapid progress in speaking the language.

$150.00 - Hardcover

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

| The following article is from the Spring, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

The Heart Essence of the Great Perfection

by His Holiness the Dalai Lama translated by Thupten Jinpa and Richard Barron foreword by Sogyal Rinpoche edited by Patrick Gaffney 272 pages, 8 pages of photos, 6x9 1-55939-157-X, $24.95 cloth Available Now

His Holiness the Dalai Lama brings to his explanation of Dzogchen a perspective and breadth which are unique...To receive such teachings from His Holiness is, I feel, something quite extraordinary.Sogyal Rinpoche, author of The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

The following is an excerpt from the book.

The Ground, Path and Fruition of Dzogchen

Let us now consider the teachings particular to the Secret Mantra Vehicle of the early transmission school of the Nyingma tradition, and what these teachings say about the three phases of ground, path, and fruition. The way in which the ground of being abides, as this is definitively understood and described in the Nyingma teachings, entails its essence, its nature, and its energy, or responsiveness. In particular, the first two aspects define the ground for the Nyingma school, its essence being primordial purity or kodak, and its nature being spontaneous presence or Ihundrup.

Nagarjuna, in his Fundamental Treatise on the Middle Way called Wisdom', states:

The dharma that is taught by the buddhas,

Relies completely upon two levels of truth:

The worldly conventional level of truth,

And the ultimate level of truth.

All that is knowableall phenomena and all that is comprised within an individual's mind and bodyis contained within these two levels of truth, conventional and ultimate. In the Dzogchen context, the explanation given would be in terms of primordial purity and spontaneous presence, and this is analogous to a passage in the scriptures:

It is mind itself that sets in place the myriad array

Of beings in the world, and the world that contains them.

That is to say, if we consider the agent responsible for creating sam- sara and nirvana, it comes down to mind. The Sutra on the Ten Grounds states, These three realms are mind only. In his commentary to his own work, Entering the Middle Way Candrakirti elaborates on this quotation, stating that there is no other creative agent apart from mind.

When mind is explained from the point of view of the Highest Yoga Tantra teachings and the path of mantra, we find that many different levels or aspects of mind are discussed, some coarser and some more subtle. But at the very root, the most fundamental level embraced by these teachings is mind as the fundamental, innate nature of mind. This is where we come to the distinction between the word sem in Tibetan, meaning ordinary mind' and the word rigpa signifying pure awareness'. Generally speaking, when we use the word sem, we are referring to mind when it is temporarily obscured and distorted by thoughts based upon the dualistic perceptions of subject and object. When we are discussing pure awareness, genuine consciousness or awareness free of such distorting thought patterns, then the term rigpa is employed. The teaching known as the Four Reliances' states: Do not rely upon ordinary consciousness, but rely upon wisdom. Here the term narnshe, or ordinary consciousness, refers to mind involved with dualistic perceptions. Yeshe', or wisdom, refers to mind free from dualistic perceptions. It is on this basis that the distinction can be made between ordinary mind and pure awareness.

When we say that mind' is the agent responsible for bringing the universe into being, we are talking about mind in the sense of rigpa, and specifically its quality of spontaneous presence. At the same time, the very essence of that spontaneously present rigpa is timelessly empty, and primordially puretotally pure by its very natureso there is a unity of primordial purity and spontaneous presence. The Nyingma school distinguishes between the ground itself, and the ground manifesting as appearances through the eight doorways of spontaneous presence', and this is how this school accounts for all of the perceptions, whether pure or impure, that arise within the mind. Without ever deviating from basic space, these manifestations and the perceptions of them, pure or impure, arise in all their variety. That is the situation concerning the ground, from the point of view of the Nyingma school.

On the basis of that key point, when we talk about the path, and if we use the special vocabulary of the Dzogchen tradition and refer to its own extraordinary practices, the path is twofold, that of trekcho and togal. The trekcho approach is based upon the primordial purity of mind, kadak, while the togal approach is based upon its spontaneous presence, lhundrup. This is the equivalent in the Dzogchen tradition of what is more commonly referred to as the path that is the union of skilful means and wisdom.

When the fruition is attained through relying on this twofold path of trekcho and togal, the inner lucidity' of primordial purity leads to dharmakaya, while the outer lucidity' of spontaneous presence leads to the rupakaya. This is the equivalent of the usual description of dharmakaya as the benefit that accrues to oneself and the rupakaya as the benefit that comes to others. The terminology is different, but the understanding of what the terms signify is parallel. When the latent, inner state of bud- dhahood becomes fully evident for the practitioner him or herself, this is referred to as inner lucidity' and is the state of primordial purity, which is dharmakaya. When the natural radiance of mind becomes manifest for the benefit of others, its responsiveness accounts for the entire array of form manifestations, whether pure or impure, and this is referred to as outer lucidity', the state of spontaneous presence which comprises the rupakaya.

In the context of the path, then, this explanation of primordial purity and spontaneous presence, and what is discussed in the newer schools of Highest Yoga Tantra both come down to the same ultimate point: the fundamental innate mind of clear light.

What, then, is the profound and special feature of the Dzogchen teachings? According to the more recent traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, collectively known as the Sarma schools of the Secret Mantra Vehicle, in order for this fundamental innate mind of clear light to become fully evident, it is necessary first of all for the coarser levels of ordinary mind, caught up with thoughts and concepts, to be harnessed by yogas, such as the yoga of vital energies, pranayoga, or the yoga of inner heat, tummo. On the basis of these yogic practices, and in the wake of those adventitious thought patterns of ordinary mind being harnessed and purified, the fundamental innate mind of clear light-'mind' in that sense becomes fully evident.

From the point of view of Dzogchen, the understanding is that the adventitious level of mind, which is caught up with concepts and thoughts, is by its very nature permeated by pure awareness. In an experiential manner, the student can be directly introduced by an authentic master to the very nature of his of her mind as pure awareness. If the master is able to effect this direct introduction, the student then experiences all of these adventitious layers of conceptual thought as permeated by the pure awareness which is their nature, so that these layers of ordinary thoughts and concepts need not continue. Rather, the student experiences the nature that permeates them as the fundamental innate mind of clear light, expressing itself in all its nakedness. That is the principle by which practice proceeds on the path of Dzogchen.

The Role of an Authentic Guru

So in Dzogchen, the direct introduction to rigpa requires that we rely upon an authentic guru, who already has this experience. It is when the blessings of the guru infuse our mindstream that this direct introduction is effected. But it is not an easy process. In the early translation school of the Nyingma, which is to say the Dzogchen teachings, the role of the master is therefore crucial.

In the Vajrayana approach, and especially in the context of Dzogchen, it is necessary for the instructions to be given by a qualified master. That is why, in such approaches, we take refuge in the guru as well as in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. In some sense, it is not sufficient simply to take refuge in the three sources of refuge; a fourth element is added, that of taking refuge in the guru. And so we say, I take refuge in the guru; I take refuge in the Buddha; I take refuge in the Dharma; I take refuge in the Sangha. It is not so much that the guru is in any way separate or different from the Three Jewels, but rather that there is a particular value in counting the guru separately. I have a German friend who said to me, You Tibetans seem to hold the guru higher than the Buddha. He was astonished. But this is not quite the way to understand it. It is not as though the guru is in any way separate from the Three Jewels, but because of the crucial nature of our relationship with the guru in such practice and teachings, the guru is considered of great importance.

Now this requires that the master be qualified and authentic. If a master is authentic, he or she will be either a member of the sangha that requires no more training, or at least the sangha that still requires training but is at an advanced level of realization. An authentic guru, and I stress the word authentic','must fall into one of these two categories. So it is because of the crucial importance of a qualified and authentic guru, one who has such realization, that such emphasis is placed, in this tradition, on the role of the guru. This may have given rise to a misconception, in that people have sometimes referred to Tibetan Buddhism as a distinct school of practice called Lamaism', on account of this emphasis on the role of the guru. All that is really being said is that it is important to have a master, and that it is important for that master to be authentic and qualified.

Even in the case of an authentic guru, it is crucial for the student to examine the guru's behaviour and teachings. You will recall that earlier I referred to the Four Reliances.' These can be stated as follows: