Bodhisattva's Jewel Garland:

A Root Text of Mahāyāna Instruction from the Precious Kadam Scripture

Excerpted from Kadam: Stages of the Path, Mind Training, and Esoteric Practice, Part One

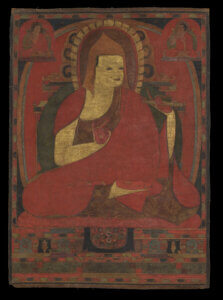

Atisha

Atīśa Dīpaṃkara Śrījñāna, the eleventh-century Indian Buddhist scholar and saint, came to Tibet at the invitation of the king of Western Tibet, Lha Lama Yeshe Wo, and his nephew, Jangchub Wo. His coming initiated the period of the second transmission of Buddhism to Tibet, formative for the Sakya Kagyu and Gelug traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. His chief disciple Dromtön went on to found the Kadampa tradition. Atisha's most celebrated text, Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, sets forth the entire Buddhist path within the framework of three levels of motivation on the part of the practitioner. Atisha's text thus became the source of the lamrim tradition, or graduated stages of the path to enlightenment, an approach to spiritual practice incorporated within all schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

Atisha

Atīśa Dīpaṃkara Śrījñāna, the eleventh-century Indian Buddhist scholar and saint, came to Tibet at the invitation of the king of Western Tibet, Lha Lama Yeshe Wo, and his nephew, Jangchub Wo. His coming initiated the period of the second transmission of Buddhism to Tibet, formative for the Sakya Kagyu and Gelug traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. His chief disciple Dromtön went on to found the Kadampa tradition. Atisha's most celebrated text, Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, sets forth the entire Buddhist path within the framework of three levels of motivation on the part of the practitioner. Atisha's text thus became the source of the lamrim tradition, or graduated stages of the path to enlightenment, an approach to spiritual practice incorporated within all schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

-

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part Two$49.95- Hardcover

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part Two$49.95- HardcoverBy Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Sarah Harding

Contributions by Taranatha

Contributions by Atisha -

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment$19.95- Paperback

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment$19.95- PaperbackBy Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited by Ruth Sonam

By Atisha

Translated by Ruth Sonam

- Bestsellers Tibetan 1 item

- Treasury of Precious Instructions 1 item

- Buddhist Academic 2item

- Buddhist Biography/Memoir 1 item

- Buddhist History 1 item

- Buddhist Overviews 1 item

- Buddhist Philosophy 1 item

- Dependent Origination 1 item

- Four Noble Truths 1 item

- Introductions to Buddhism 2item

- Dalai Lamas 2item

- Kadam Tradition 2item

- Shangpa Kagyu 1 item

- Karmapas 1 item

- Lam Rim 1 item

- Mahamudra 1 item

GUIDES

Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland: An Excerpt from Kadam, Part One

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

Translated by Artemus B. Engle

About Kadam

The third volume of this series covers the teachings and practices of the Kadam lineage. This tradition is based on the teachings of the Indian master Atiśa, who traveled to Tibet in the early eleventh century and stayed for twelve years transmitting teachings that would be embraced by many traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. The three categories of teachings covered here and in the fourth volume of the series—Stages of the Path, Mind Training, and Esoteric Instructions—correspond to three root texts: Atiśa’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, the aphorisms of the Seven-Point Mind Training, and Atiśa’s Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland. This volume also contains ritual texts on the bodhisattva vow conferral, as well as commentaries by Tsongkhapa, Tāranātha, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, and Jamgön Kongtrul, himself. The fourth volume of The Treasury of Precious Instructions series extends these commentaries and includes material on the esoteric instructions known as the Sixteen Drops.

About The Treasury of Precious Instructions

The Treasury of Precious Instructions by Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Taye, one of Tibet’s greatest Buddhist masters, is a shining jewel of Tibetan literature, presenting essential teachings from the entire spectrum of practice lineages that existed in Tibet. In its eighteen volumes, Kongtrul brings together some of the most important texts on key topics of Buddhist thought and practice as well as authoring significant new sections of his own.

Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland

Chapter 3, page 19-23

By Atiśa

Translated by Thupten Jinpa

Sanskrit title: Bodhisattvamaṇevalī

Homage to great compassion.

Homage to the teachers.

Homage to the faith divinities.

Discard all lingering doubts,

and strive with dedication in your practice.

Thoroughly relinquish sloth, mental dullness, and laziness,

and strive always with joyful perseverance. (1)

With mindfulness, vigilance, and conscientiousness,

constantly guard the gateways of your senses.

Again and again, three times both day and night,

examine the flow of your thoughts. (2)

Reveal your own shortcomings,

but do not seek out others’ errors.

Conceal your own good qualities,

but proclaim those of others. (3)

Forsake wealth and ministrations;

at all times relinquish gain and fame.

Have modest desires, be easily satisfied,

and reciprocate kindness. (4)

Cultivate love and compassion,

and stabilize your awakening mind.

Relinquish the ten negative actions,

and always reinforce your faith. (5)

Destroy anger and conceit,

and be endowed with humility.

Relinquish wrong livelihood,

and be sustained by ethical livelihood. (6)

Forsake material possessions,

embellish yourself with the wealth of the noble ones.

Avoid all trifling distractions,

and reside in the solitude of wilderness. (7)

Abandon frivolous words;

constantly guard your speech.

When you see your teachers and preceptors,

reverently generate the wish to serve. (8)

Wise beings with dharma eyes

and beginners on the path as well—

recognize them as your spiritual teachers.

In fact when you see any sentient being,

view them as your parent, your child, or your grandchild. (9)

Renounce negative friendships,

and rely on a spiritual friend.

Dispel hostility and unpleasantness,

and venture forth to where happiness lies. (10)

Abandon attachment to all things

and abide free of desire.

Attachment fails to bring even the higher realms;

in fact, it kills the life of true liberation. (11)

When you encounter the causes of happiness,

in these always persevere.

Whichever task you take up first,

address this task primarily.

In this way, you ensure the success of both tasks,

where otherwise you accomplish neither. (12)

Since you take no pleasure in negative deeds,

when a thought of self-importance arises,

at that instant deflate your pride

and recall your teacher’s instructions. (13)

When discouraged thoughts arise,

uplift your mind

and meditate on the emptiness of both.

When objects of attraction or aversion appear,

view them as you would illusions and apparitions. (14)

When you hear unpleasant words,

view them as mere echoes.

When injuries afflict your body,

see them as the fruits of past deeds. (15)

Dwell utterly in solitude, beyond town limits.

Like the carcass of a wild animal,

hide yourself away in the forest

and live free of attachment. (16)

Always remain firm in your commitment.

When a hint of procrastination and laziness arises,

at that instant enumerate your flaws

and recall the essence of spiritual conduct. (17)

However, if you do encounter others,

speak peacefully and truthfully.

Do not grimace or frown,

but always maintain a smile. (18)

In general, when you see others,

be free of miserliness and delight in giving;

relinquish all thoughts of envy. (19)

To help soothe others’ minds,

forsake all disputation

and be endowed with forbearance. (20)

Be free of flattery and fickleness in friendship;

be steadfast and reliable at all times.

Do not disparage others,

but always abide with a respectful demeanor. (21)

When giving advice,

maintain compassion and altruism.

Never defame the teachings.

Whatever practices you admire,

with aspiration and the ten spiritual deeds,

strive diligently, dividing day and night. (22)

Whatever virtues you gather through the three times,

dedicate them toward the unexcelled great awakening.

Disperse your merit to all sentient beings,

and utter the peerless aspiration prayers

of the seven limbs at all times. (23)

If you proceed thus, you’ll swiftly perfect merit and wisdom

and eliminate the two defilements.

Since your human existence will be meaningful,

you’ll attain the unexcelled enlightenment. (24)

The wealth of faith, the wealth of morality,

the wealth of giving, the wealth of learning,

the wealth of conscience, the wealth of shame,

and the wealth of insight—these are the seven riches. (25)

These precious and excellent jewels

are the seven inexhaustible riches.

Do not speak of these to those not human.

Among others guard your speech;

when alone guard your mind. (26)

This concludes the Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland composed by the Indian abbot Dīpaṃkara Śrījñāna.

Books Related to Kadam

Tibetan Masters of the 10th-11th Centuries

Masters of the 10th-11th Centuries

Tibetan Masters of the 10th-11th Centuries

During this period, there was an influx of new translations, teachers from India who formed the Kadam, Kagyu, and Sakya schools as well as some important Nyingma figures.

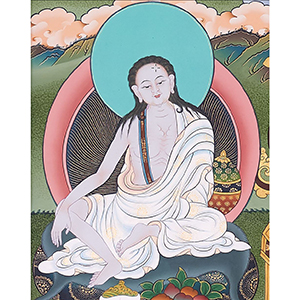

Atiśa Dīpankara Śrījñāna (982–1054 CE)

11th century

The Indian master Atisha's importance to Tibetan Buddhism cannot be overstated. He founded the Kadam school with his students which influenced all the lineages in Tibet. Explore the many works by and about his here.

Rongzom Chökyi Zangpo (1012–1088)

11th century

Rongzom Chökyi Zangpo (1012–1088)—also known as Rongzompa, Rongzom Mahapandita, Rongzom Chozang, and Dharmabhadra— is along with Longchenpa and Mipham Rinpoche, one of the pillars of the Nyingma tradition who systematized much of the philosophical principles of the school.

Tilopa (988-1068)

11th century

One of the great 84 Mahasiddhas and the root of much of the Kagyu tradition, explore ten books related to this great tantric master.

Naropa (1016-1100)

11th century

The famous student of Tilopa and guru to Marpa, explore the fascinating life and teachings of Naropa.

Marpa (1012-1096)

11th century

The student of Naropa as well as the guru to both Maitripa and Milarepa, Marpa was the Tibetan founder of the Kagyu tradition.

Milarepa (1040-1123)

10th-11th centuries

Tibet's "patron-saint" and yogi par excellence. Beloved by all the schools, his life exemplifies the complete Buddhist path.

Gampopa (born 1079)

11th century

The great Gampopa, aka Dakpo Lhaje, the physician from Lhaje, was a monk whose systemization of the Kagyu teachings form the root of the Drikung, Drukpa, and Karma branches of the Kagyu tradition.

Indian Mahayana Masters of the 2nd-8th Centuries

The Indian Masters

Indian Mahayana Masters from the 2nd-8th Centuries

The Tibetan traditions all look back to India as the source of wisdom. There were countless masters all over India, north and south, east (including present-day Bangladesh) and west (including present-day Pakistan). The Mahayana reached its full expression during this period, and what follows is a partial but growing list of Reader Guides to these masters.

The Seventeen Pandits of Nalanda

2nd through 11th centuries

Tibetan Buddhism is none other than the Buddhism of India in the tradition of Nalanda, the great center of Buddhist learning that was located in present-day Bihar, India. There are seventeen great scholars profiled here, including Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Asanga, Vasabandhu, Buddhapalita, Dignaga, Bhavaviveka, Vimuktisena, Chandrakirti, Dharmakirti, Shantideva, Shantarakshita, Kamalashila, Haribhadra, Gunaprabha, Shakyaprabha. and Atisha.

Nagarjuna

(2nd century....and beyond)

The great master closely associated with the Perfection of Wisdom

Shantideva and the Way of the Bodhisattva

8th century

The great master Shantideva is the author of two very important texts. The first is the Śikṣāsamuccaya, or Training Anthology which is a compilation of many works. The second is the Bodhicharyavatara, or Way of the Bodhisattva. This Reader Guide focuses on the latter work.

Asanga

4th century

The great Mahayana figure who is a key explicator of Yogacara, and also received the Five Maitreya texts from Maitreya.

Xuanzang (602-664 CE)

7th century

While not an Indian master, we wanted to include Xuanzang, certainly one of the most important figures in Buddhist history. His 16 year pilgrimage from his home in China throughout the Buddhist world is almost The Odyssey of the Buddhist literature. His translation and preservation of texts, as well as the account of his journey, had come down to us through the ages and is well worth a deep exploration.

The Life of Atiśa Dīpankara Śrījñāna (982–1054 CE)

Atīśa Dīpaṃkara Śrījñāna, was an eleventh-century Indian Buddhist scholar and saint who came to Tibet at the invitation of the king of Western Tibet, Lha Lama Yeshe Wo, and his nephew, Jangchub Wo. His coming initiated the period of the second transmission of Buddhism to Tibet, formative for the Sakya, Kagyu and Gelug traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. His chief disciple Dromtön went on to found the Kadampa tradition. Atisha's most celebrated text, Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, sets forth the entire Buddhist path within the framework of three levels of motivation on the part of the practitioner. Atisha's text thus became the source of the lamrim tradition, or graduated stages of the path to enlightenment, an approach to spiritual practice incorporated within all schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

If someone were to fill with jewels

As many Buddhafields as there are grains

Of sand in the Ganges

To offer to the Protector of the World,

This would be surpassed by

The gift of folding one's hands

And inclining one's mind to enlightenment

For such is limitless.

"Atiśa’s life and teachings are a Tibetan story, and what an amazing story it is. Atiśa’s life is guided by dreams, visions, and pre-dictions from buddhas and bodhisattvas, including the savioress Tārā. In the story of Atiśa’s life, we enter a world of gold, sailing ships, palm leaf manuscripts, and mantras, rather than credit cards, automobiles, social media, and cell phones. The story involves transactions in over two million dollars’ worth of gold and travels throughout maritime Buddhist Asia. The Tibetans have faithfully preserved what is known of Atiśa Dīpaṃkaraśrījñāna, the vicissitudes of his life, the struggles in his travels, and the spirit and meaning of his teachings."

—James B. Apple, from the Preface to Atisa Dipamkara: Illuminator of the Awakened

Paperback | Ebook

$22.95 - Paperback

On the Path to Enlightenment

Heart Advice from the Great Tibetan Masters

By Matthieu Ricard

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche inspired Matthieu Ricard to create this anthology by telling him that “when we come to appreciate the depth of the view of the eight great traditions [of Tibetan Buddhism] and also see that they all lead to the same goal without contradicting each other, we think, ‘Only ignorance can lead us to adopt a sectarian view.’” Ricard has selected and translated some of the most profound and inspiring teachings from across these traditions.

The selected teachings are taken from the sources of the traditions, including the Buddha himself, Nagarjuna, Guru Rinpoche, Atisha, Shantideva, and Asanga; from great masters of the past, including Thogme Zangpo, the Fifth Dalai Lama, Milarepa, Longchenpa, and Sakya Pandita; and from contemporary masters, including the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Mingyur Rinpoche. They address such topics as the nature of the mind; the foundations of taking refuge, generating altruistic compassion, acquiring merit, and following a teacher; view, meditation, and action; and how to remove obstacles and make progress on the path.

Atisha's Lamp for the Path of Awakening (Bodhipathapradīpa)

The Lamp for the Path of Awakening is Atisha's most famous treatise which provided the foundation for the lamrim, or the "graded path," tradition of which all the schools (specifically Kadampa and Gelug) subsequently adopted.

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

With Commentary by Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Edited and translated by Ruth Sonam

Atisha's most celebrated text, Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, sets forth the entire Buddhist path within the framework of three levels of motivation on the part of the practitioner. Atisha's text thus became the source of the lamrim tradition, or graduated stages of the path to enlightenment, an approach to spiritual practice incorporated within all schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

"Geshe Sonam Rinchen's lucid and engaging commentary draws out Atisha's meaning for today's practitioners with warmth and wit, bringing the light of this age-old wisdom into the modern world."—Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies

Paperback| Ebook

$16.95 - Paperback

An Introduction to Buddhism

Teachings on the Four Noble Truths, The Eight Verses on Training the Mind, and the Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

By H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

This classic collection of texts on the meditation practice and theory of Dzogchen presents the Great Perfection through the writings of its supreme authority, the fourteenth-century Tibetan scholar and visionary Longchen Rabjam. The pinnacle of Vajrayana practice in the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, Dzogchen embodies a system of training that awakens the intrinsic nature of the mind to reveal its original essence, utterly perfect and free from all duality—buddha nature, or buddhahood itself.

In The Practice of Dzogchen, Tulku Thondup translates essential passages from Longchen Rabjam’s voluminous writings to illuminate and clarify this teaching. He also draws on the works of later masters of the tradition, placing Dzogchen in context both in relation to other schools of Buddhism and in relation to the nine-vehicle outline of the Buddhist path described in the Nyingma tradition. This expanded edition includes Counsel for Liberation, Longchenpa’s poetic exhortation to readers to quickly enter the path of liberation, the first step toward the summit of Dzogchen practice.

This book was previously published under the title Lighting the Way.

See more from The Core Teachings of the Dalai Lama series

Atisha and the tradition of Lojong, "Mind Training"

"This tradition of summarizing the trainings into seven key points was the lineage that Chekawa Yeshe Dorje recorded. It has become widely known as “The Seven Key Points of Mind Training.” Chekawa Yeshe Dorje was not a direct student of Atisha, nor was he a direct student of Dromtönpa. Rather, the trainings came to him some years later, after being passed on from teacher to disciple in an unbroken line. Chekawa Yeshe Dorje received many instructions from the lineage of practitioners of Atisha, synthesized them, and wrote them down in seven key points."

Paperback | Ebook

$18.95 - Paperback

The Power of Mind

A Tibetan Monk's Guide to Finding Freedom in Every Challenge

By Khentrul Lodro T'haye and translated by Paloma Lopez Landry

We’ve all heard platitudes about cultivating love and compassion, but how can we really develop these qualities in ourselves and—crucially—share them in our world? The Power of Mind provides a proven path.

Khentrul Rinpoche teaches that regardless of what’s unfolding in our lives, our route to freedom lies in our minds—and how we work with them. A thousand years ago, the Indian saint Atisha endured great hardship to bring the Buddha’s teachings to Tibet, where they flourished. This book introduces a primary text that emerged—the Seven Key Points of Mind Training.

Paperback | Ebook

$24.95 - Paperback

The Art of Transforming the Mind

A Meditator's Guide to the Tibetan Practice of Lojong

By B. Alan Wallace

The purpose of lojong, a traditional Mahayana Buddhist practice of training the mind, is about transforming one’s attitude and expanding one’s sense of self to encompass the greater whole. In this modern presentation of lojong practice and Atisha’s Seven-Point Mind Training, author, translator, and Buddhist practitioner B. Alan Wallace gives readers a framework from which they may cultivate the qualities of loving-kindness, compassion, and insight while diminishing harmful habits and ways of thinking. “All of us have attitudes,” Wallace explains, and “attitudes need adjusting.” The practice of lojong is therefore presented as a method to shift our attitude away from our problems, anxieties, hopes, and fears toward an expansive sense of joy and well-being that springs from the very essence of Mahayana—bodhichitta.

Includes three new translations of Atisha’s source material including Pith Instructions on a Single Mindfulness and Pith Instructions on the Middle Way.

Paperback | Ebook

$21.95 - Paperback

The Intelligent Heart

A Guide to a Compassionate Life

By Dzigar Kongtrul

Compassion arises naturally when one comes to perceive the lack of solid distinction between self and other. The Buddhist practice known as tonglen—in which one consciously exchanges self for other—is a skillful method for getting to that truthful perception. In this, his commentary on the renowned Tibetan lojong (mind training) text the Seven Points of Mind Training, Dzigar Kongtrul reveals tonglen to be the true heart and essence of all mind-training practices. He shows how to train the mind in a way that infuses every moment of life with uncontrived kindness toward all.

Classics of Lojong, "Mind Training"

One of the more prominent texts on lojong from the 19th century is Jamgon Kongtrul's The Great Path of Awakening. This text is from a collection of texts known as The Five Treasuries in which Kongtrul embraces the Ri-me (non-sectarian) impulse of the 19th century. Along with a number of teachers including Khyentse Wangpo, Dza Patrul, and Chokgyur Lingpa, Kongtrul aimed to preserve rare teachings and to re-emphasize practicing dharma in everyday life. His presentation of The Seven Points of Mind Training both preserves Tibet's incredible history and illuminates the practice of lojong for his generation and generations to come. There are a number of modern commentaries that continue in the tradition of Kongtrul's commentary on lojong and the tradition of Atisha including Pema Chödron's Start Where You Are and Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche's Training the Mind and Cultivating Loving-Kindness. It goes without saying, it is because of great texts like The Great Path of Awakening that the tradition of lojong continues to inspire teachers and practitioners today.

"Earlier in his life Atisha had experienced numerous visions and dreams that consistently pointed out the necessity of bodhicitta for the attainment of buddhahood. He was led to em-bark on a long sea journey to Indonesia to meet Serlingpa, from whom he received the teachings of mind training in the mahayana tradition. In this system, one’s way of experiencing situations in everyday life is transformed into the way a bodhisattva might experience those situations"

-from the Preface to The Great Path of Awakening

Paperback

$16.95 - Paperback

The Great Path of Awakening

The Classic Guide to Lojong, A Tibetan Practice for Cultivating the Heart of Compassion

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye and translated by Ken McLeod

Here is a practical Buddhist guidebook that offers techniques for developing a truly compassionate heart in the midst of everyday life. For centuries, Tibetans have used fifty-nine pithy slogans—such as "A joyous state of mind is a constant support" and "Don't talk about others' shortcomings"—as a means to awaken kindness, gentleness, and compassion. While Tibetan Buddhists have long valued these slogans, recently they have become popular in the West due to such books as Start Where You Are by Pema Chödrön and Training the Mind by Chögyam Trungpa.

This edition of The Great Path of Awakening contains an accessible, newly revised translation of the slogans from the famous text The Seven Points of Mind Training. It also includes illuminating commentary from Jamgon Kongtrul that provides further instruction on how to meet every situation with intelligence and an open heart.

"In our era, when so many people are seeking help to relate to their own feelings of woundedness and at the same time wanting to help relieve the suffering they see around them, the ancient teachings presented here are especially encouraging and to the point. When we find that we are closing down to ourselves and to others, here is instruction on how to open. When we find that we are holding back, here is instruction on how to give. That which is unwanted and rejected in ourselves and in others can be seen and felt with honesty and compassion. This is teaching on how to be there for others without withdrawing."

Paperback | Ebook

$19.95 - Paperback

Start Where you Are

A Guide to Compassionate Living

By Pema Chödron

We all want to be fearless, joyful, and fully alive. And we all know that it’s not so easy. We’re bombarded every day with false promises of ways to make our lives better—buy this, go here, eat this, don’t do that; the list goes on and on. But Pema Chödrön shows that, until we get to the heart of who we are and really make friends with ourselves, everything we do will always be superficial. Here she offers down-to-earth guidance on how we can go beyond the fleeting attempts to “fix” our pain and, instead, to take our lives as they are as the only path to achieve what we all yearn for most deeply—to embrace rather than deny the difficulties of our lives. These teachings, framed around fifty-nine traditional Tibetan Buddhist maxims, point us directly to our own hearts and minds, such as “Always meditate on whatever provokes resentment,” “Be grateful to everyone,” and “Don’t expect applause.” By working with these slogans as everyday meditations, Start Where You Are shows how we can all develop the courage to work with our own inner pain and discover true joy, holistic well-being, and unshakeable confidence.

Includes the Root Text of the Seven Points of Training the Mind, by Chekawa Yeshe Dorje

Paperback | Ebook

$16.95 - Paperback

Warning: Using this book could be hazardous to your ego! The slogans it contains are designed to awaken the heart and cultivate love and kindness toward others. They are revolutionary in that practicing them fosters abandonment of personal territory in relating to others and in understanding the world as it is.

The fifty-nine provocative slogans presented here—each with a commentary by the Tibetan meditation master Chögyam Trungpa—have been used by Tibetan Buddhists for eight centuries to help meditation students remember and focus on important principles and practices of mind training. They emphasize meeting the ordinary situations of life with intelligence and compassion under all circumstances. Slogans include, "Don't be swayed by external circumstances," "Be grateful to everyone," and "Always maintain only a joyful mind."

This edition contains a new foreword by Pema Chödrön.

Atisha and Madhyamaka

While Atisha does not appear throughout this book on Madhyamaka, his presentation of it is discussed in several places. There is a section on the lineage of Atisha from Nargarjuna to him and then from Atisha to Dromtonpa and many others into the Kagyu tradition of Mahamudra. This book also details how in his autocommentary on the Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, Atisha is explicit in recommending the provisional use of valid cognition as presented by Dharmakirti and others when meditating on the ultimate as transmitted in Nagarjuna's pith instructions.

Atisha and Tantra

This volume of the Treasury of Knowledge presents the lineages that stem from Atisha over a few pages. Additionally, it details his role in the Jordruk or Six Branch Yoga tradition (related to Kalachakra), one of the Eight Chariots.

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part One

Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 12 (The Treasury of Precious Instructions)

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

The texts in the first volume focus on the Niguma lineage and major Shangpa tantric deity practices. The source texts on the practice of the celestial goddesses White and Red Khecarīs are by Atiśa and Lama Rāhula. Atiśa is also discussed in several places in this volume.

Of the forty texts in Volume 12, the second Shangpa book, The two celestial goddesses, manifestations of Vajrayoginī, are White Khecarī and Red Khecarī. They are practiced together in the first text in this section by Kongtrul. This is followed by Atiśa’s well-known praise of White Khecarī, also called simply Vajrayoginī. Then two practices of Consciousness Transference (’pho ba) based on the goddesses are authored by Lochen Gyurme Dechen (white) and Rāhulagupta (red).

Shangpa Kagyu: The Tradition of Khyungpo Naljor, Part Two

Essential Teachings of the Eight Practice Lineages of Tibet, Volume 12 (The Treasury of Precious Instructions)

By Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye

The second Shangpa Kagyu volume of Kongtrul's Treasury of Precious Instructions, includes Atisha's In Praise of Vajrayoginī, the Especially Exalted Praise which is also referred to in the previous volume. He is discussed in multiple places in this volume as well.

Additional Resources

SNOW LION NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE

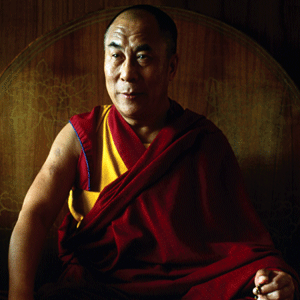

The Dalai Lama: Reliance on a Teacher

This article on reliance on a teacher originally appeared in the Snow Lion newsletter, Vol 12 #4, Fall 1997

Answers to Questions at the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center, Washington, New Jersey, September 1990

Joshua Cutler: Americans in general are very wary of relying on one person and giving that person a lot of power and control. This is difficult for American people. But on the other hand, I know that, when the teaching was coming from India to Tibet, Atisha was asked by Dromtonpa, "How is it that we Tibetans have such a good knowledge of the teachings yet no one has produced any of the realizations of the grounds and the paths?" Atisha replied that it was because Tibetans were still viewing the teacher as an ordinary person. It’s very clear to me that this teaching of faith in the spiritual teacher is the very foundation of the teaching being able to grow in this country, but there is a problem because many spiritual teachers have abused their students and so people are very suspicious of teachers. Could Your Holiness please give us guidance on this practice of relying upon the spiritual teacher?

Related Books

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

$19.95 - Paperback

By: Atisha & Geshe Sonam Rinchen & Ruth Sonam

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Atisha explicitly mentions that all the Great Vehicle realizations, be they great or small, depend on proper reliance upon a spiritual teacher. He then says that as the Tibetans view their lamas as only ordinary persons, they are not attaining realizations. His advice applies to Great Vehicle realizations.

But in giving a general explanation of Buddha’s doctrine, we have to include both the Great and Hearer Vehicles. Therefore, take for example the solitary realizers. In Maitreya’s Abhisamayalamkara, which is the root text of the lam rim lineage, he specifically mentions that solitary realizers achieve their liberation without relying on verbal guidance from another person. They attain their realizations mainly through their own introspective reflections. So we must make a distinction between general realizations and Great Vehicle realizations.

Therefore, it is in the practice of the Great Vehicle path, particularly in the practice of Great Vehicle’s tantric path, that reliance on spiritual guidance becomes indispensable. Why is this so? In my estimation, a general understanding of the framework of the Buddhist path that is common to both the Great and Hearer vehicles is something that we can develop quite clearly on our own by reading, introspective reflections, and so on. When practicing and developing the realizations of the Great Vehicle path, however, we cannot always take the Great Vehicle sutras literally. There are various levels of meaning—the literal, the interpretable, and the final meaning. There are also many differences when we consider the traditions of the different monasteries. For example, Buddha taught the selflessness of phenomena in the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, his definitive or principal teaching. The commentaries on his thought in these sutras differ in their explanation of emptiness. Therefore, in order to unravel the various intricacies in the meaning of these sutras, it is very helpful to hear the explanation of a qualified lama. Especially in the case of tantra, where there is special emphasis on using one’s afflictive emotions in the path, seeking proper guidance from someone who has actual and exact experience in this path is indispensable. Otherwise it is difficult for religious practice to be helpful. Rather, it will be only dangerous.

In the Great Vehicle literature, such as the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, there are two levels of meaning— the explicit teaching and the hidden meaning—whereas in the Hearer Vehicle sutras there is no such presentation of two levels of meaning. Therefore Maitreya called his Clear Ornament of Realization (Abhisamayalamkara) (which is a commentary on the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra) a "treatise of quintessential instructions," indicating that it contained instructions that would give us the keys to unlock the hidden meaning within the sutra. For this reason, in order to practice the Great Vehicle it is very important to rely on the spiritual teacher.

However, in the Hearer Vehicle as well, we do find sutras, such as the Sutra on Moral Discipline (Vinayasutra), in which there are instructions to rely first on the lama who teaches moral discipline, and then on other lamas who principally will show the path to liberation. Thus, doesn’t this indicate that the lama is very important?

Since reliance on a lama is a very important factor in spiritual practice, there are detailed presentations of the qualifications that are necessary for such teachers in both the Great Vehicle and Hearer Vehicle scriptures. The import of doing this is to emphasize the point that the spiritual teacher should be someone who will not mislead the students. Particularly, in tantric practice it is explained that the lama and disciple should examine each other for up to twelve years before adopting a teacher-disciple relationship.

Along with the description of the qualifications of the lama that is found in the literature on moral discipline, the question is raised of how to look for such qualities in a person who is a candidate for one’s spiritual teacher. In one of the moral discipline commentaries called The Commentary of Tso-na-wa, a reference to examining the lama can be found at the end of a section commenting on the passage in the Sutra on Moral Discipline which talks about the qualifications that are necessary for an ideal teacher. The author quotes a verse from sutra which says, "Although a fish is hidden below the water, it is revealed by the ripples on the surface." In the same way, we can understand a person’s mental qualities by examining his or her daily behavior, speech, and physical expressions.

For more on the Abhisamayalamkara and the other Five Maitreya Texts, see an interview with Karl Brunnholzl or see him discuss this below:

Also, in his Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lamrim Chenmo)Tsongkhapa presents the method for proper reliance upon the lama and lists the lama’s qualifications, particularly the ten qualifications of a Great Vehicle teacher. In this section Venerable Tsongkhapa responds to a passage from the teachings of Geshe Potawa, the Kadampa master, where the question is raised: "What if the person whom you are thinking of taking on as your spiritual teacher does not possess all these qualifications? What minimum qualifications should we seek in such a person?" Tsong-khapa gives the answer that the most important qualification is compassion for the students. As long as that person has this quality, even a single instruction that the teacher might give will be beneficial to the students. The other nine qualifications, such as skill, are necessary, but compassion is the principal quality required.

In this section Venerable Tsongkhapa also mentions nine attitudes that we must adopt when relating to our lama. To illustrate one of these attitudes, he says that we should behave like very obedient children behave toward their father. Whatever such children do, they always take into consideration the wishes of their father, and totally give themselves over to their father’s control. (This example reflects the way people thought at a certain time in India, not necessarily in today’s America.) Having said that, Venerable Tsongkhapa makes the very significant point that this analogy is made from the viewpoint of how we must relate to a fully qualified lama. He says that it is therefore very important to bear in mind that we should not simply be "led by the nose" by just anyone. In Tibetan these words are very powerful. There is a Tibetan saying that we should not allow just anyone to take the rope which is tied to our nose. This expression might have come from the Tibetan custom of tying a rope through the nose of yaks and other animals to enable the owner to lead the animal anywhere. So Venerable Tsongkhapa’s point is that we should not let just anyone have authority over us. I always refer to this quotation because it is very clear.

Furthermore Venerable Tsongkhapa substantiates his point with a quote from sutra which states, "Act in accord with that which is virtuous; do not accord with that which is not," Then in response to the question, "Is that'only in the case of the sutra path?" Venerable Tsongkhapa answers that it is the same for the tantric path as well, and supports this by citing the following quotation from the Fifty Verses of Guru Devotion, "If we find that [an instruction] is not proper through reasoning, we should say something in reply."

After Venerable Tsongkhapa gives the quote from the Cloud of Jewels Sutra, he mentions that "the meaning of not engaging in that which is improper is clarified in the Twelve Buddha Birth Stories.'' According to the birth story to which Venerable Tsongkhapa refers, Buddha was once born as a brahmin in India. One day his teacher decided to test some of his students, and summoned them to him. He said, "Nowadays I’m having very serious financial problems. Therefore you students should think about my situation."

The students replied, "Now that you are in such difficulty, we will do whatever you ask us to do."

The teacher said, "I should say something to you but you won’t do what I say."

They all protested, "We will certainly do it."

The teacher then said, "It is said, ‘When a brahmin is declining in his fortune, it is virtuous to steal.’ Brahma, the creator of the universe, is the father of all brahmins. When a brahmin is declining in fortune, it is all right to steal, because everything is Brahma’s creation, and the brahmins own those creations. Thus it is said, ‘When a brahmin is declining in his fortune, it is virtuous to steal.’ Therefore, please go and steal something."

Most of the students replied that they would do just as the teacher said, but the student who was to become Shakyamuni Buddha remained silent.

The teacher asked him, "You are my student. When I have such difficulty, why are you not saying anything?"

The student said, "You, my teacher, have instructed us to steal, but according to the general teachings stealing is completely improper. Although you have said to do it, it doesn’t seem right."

The teacher was very pleased and said, "I said this in order to test you all. He is the one who has actually understood my teaching. He has not been led foolishly anywhere like the front of a rivulet of water, but has examined what his teacher has said, and made his own determination. He is the best among my students."

Therefore, if we have understood well the complete approach to the path in the Great Vehicle scriptures, there will be no problems. But the lama also has to be cautious. Therefore as a concluding remark, after mentioning the qualifications of the lama in this section on proper reliance on the spiritual teacher, Venerable Tsongkhapa says that those who wish to seek students and become teachers must examine whether they have all these qualifications, and then achieve those that they lack. Similarly the students who wish to seek a lama must also examine whether the potential lama has these qualifications, and rely on a lama who has them. Otherwise, if the student is ignorant of these factors and then comes into contact with a teacher who is also very presumptuous and greedy, both are put in a very difficult position.

At the end of the section on special insight in the Great Exposition, Venerable Tsongkhapa mentions that if disciples have strong faith but do not have intelligence, they can be led foolishly anywhere, just like the front of a rivulet of water. They will do whatever they are told. We should not be like this.

We should understand these points. So, I think it is very important to make people aware of these points by writing articles in papers, journals, and so on, especially when you know that there is some danger to the integrity of the teachings because of cases where people have taken on the role of teacher and then exploited the trust of their students.

Do you have any further questions regarding this point?

Vikki Urubshurow: In the biography of the famous Naropa there are many seemingly unethical acts. Why is this such an important text?

His Holiness: I always say that if it is a case of the teacher being as highly qualified as Tilopa, and the student being as highly qualified as Naropa, then it is completely exceptional. However, it is very difficult to find a teacher who has such high qualifications as Tilopa and also very difficult to find a student who has the qualifications of Naropa.

There is a Tibetan saying that states, "If the fox tries to jump where the lion can jump, the fox will break its spine."

When teachers give instructions on how to practice proper reliance on the spiritual teacher, they emphasize different points of the practice. Some teachers assume that the teacher and the student have the complete qualifications, and stress following such good examples of the teacher-disciple relationship as those of Naropa and Tilopa, Milarepa and Marpa Lotsawa, and Shon-nu-nor-sang and his teacher. Nowadays, it is a time of unfavorable conditions. Therefore, Venerable Tsongkhapa’s approach is more well-balanced. This is very important to understand.

It is dangerous to assume that you can give instructions on the practice of faith and the use of pure perception (dog snang). Rather it is better that both the teacher and disciple examine one another, using analysis just as we do when studying the philosophical texts. Isn’t this approach much more reliable?

More on the student-teacher relationship:

The Teacher-Student Relationship

$24.95 - Paperback

By: Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye & Ron Garry & Ven. Gyatrul Rinpoche & Lama Tharchin

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is considered the foremost Buddhist leader of our time. The exiled spiritual head of the Tibetan people, he is a Nobel Peace Laureate, a Congressional Gold Medal recipient, and a remarkable teacher and scholar who has authored over one hundred books.

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is considered the foremost Buddhist leader of our time. The exiled spiritual head of the Tibetan people, he is a Nobel Peace Laureate, a Congressional Gold Medal recipient, and a remarkable teacher and scholar who has authored over one hundred books.

Books by H.H. The Dalai Lama

The Gelug View on Choosing an Object of Observation

The Gelug View on Choosing an Object of Observation

from

Study and Practice of Meditation

by Leah Zahler

To choose an object of observation, a meditator may “investigate among various objects such as a Buddha image to see what works well”—that is, the meditator may try them out—or “read texts to see what objects of observation are recommended,” or “seek the advice of a virtuous spiritual friend, or guide (dge ba’i bshes gnyen, kalyanamitra)—a lama (bla ma, guru) who can identify a suitable object of observation”; although meditators of sharp faculties are able to choose an object of observation by studying the texts and trying out the objects of observation set forth in them, most people need to rely on a teacher.

Ge-luk-pas, however, refute the position that that any object of observation that seems easy or comfortable will do. Rather, the object of observation has to be one that will pacify the mind. Therefore, an object that arouses desire or hatred is not suitable. According to Gedün Lodrö, the erroneous position that any easy or comfortable object of observation is suitable stems from a misinterpretation of a line from Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, which Gedün Lodrö interprets in the context of changing the object of observation as, “One should set one’s virtuous mind on any one object.” It can also be understood as an exaggeration of the valid position that for an inexperienced meditator, the cultivation of calm abiding is difficult and that, therefore, the object of observation should not also be difficult.

Meditators who have one of the five predominant afflictive emotions—desire, hatred, obscuration, pride, and discursiveness—must pacify the predominant afflictive emotion by using the specific object of observation that is an antidote to it; they are unable to use any other object of observation successfully until they have done so. The objects of observation that pacify the five predominant afflictive emotions are called objects of observation for purifying behavior. However, someone whose afflictive emotions are of equal strength or who has few afflictive emotions may use any of the objects of observation set forth in the Ge-luk system. Since the body of a Buddha is considered the best object of observation in this system, it would be seen as the most suitable object of observation for such a person.

Leah Zahler, a poet and scholar, graduated from Smith College and received a PhD in Buddhist Studies from the University of Virginia.

Recent Books on Meditation and Mindfulness

| The following article is from the Spring, 2001 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

by B. Alan Wallace

ISBN: 9781559392006

...an extraordinary book. Howard Cutler, co-author of The Art of Happiness

All of us have attitudes. Some of them accord with reality and serve us well throughout the course of our lives. Others are out of alignment with reality, and cause us problems.

Tibetan Buddhist practice isn't just sitting in silent meditation, it's developing fresh attitudes that align our minds with reality. Attitudes need adjusting, just like a spinal column that has been knocked out of alignment. B. Alan Wallace explains a fundamental type of Buddhist mental training called lojong, which can literally be translated as attitudinal training. It is designed to shift our attitudes so that our minds become pure well-springs of joy instead of murky pools of problems, anxieties, fleeting pleasures, hopes and frustrations.

The author draws on his thirty-year training in Buddhism, physics, the cognitive sciences, and comparative religion to challenge readers to reappraise many of their assumptions about the nature of the mind and physical world.

The following is an excerpt from the Preface of the book.

In this book I will explain a type of mental training Tibetans call lojong. The Tibetan word lojong is made up of two parts: lo means attitude, mind, intelligence, and perspective; and jong means to train, purify, remedy, and clear away. So the word lojong could literally be translated as attitudinal training, but I'll stick with the more common translation of mind-training.

Over the past millennium, Tibetan lamas have devised many lojongs, but the most widely taught and practiced of all lojongs in the Tibetan language was one based on the teachings of an Indian Buddhist sage named Atisha (982-1054), whose life spanned the end of the first millennium of the common era and the beginning of the second. Atisha brought to Tibet an oral tradition of lojong teachings that was based on instructions that had been passed down to him through the lineage of the Indian Buddhist teachers Maitriyogin, Dhamiarakshita, and Serlingpa. This oral tradition may represent the earliest such practice that was explicitly called a lojong, and it is probably the most widely practiced in the whole of Tibetan Buddhism. This training was initially given only as an oral instruction for those students who were deemed sufficiently intelligent and highly enough motivated to make good use of it. Only about a century after Atisha's death was this secret training written down and made more widely available in monasteries and hermitages, Tibet's unique kinds of attitudinal correction facility. This delay probably accounts for the minor variations in the different versions of the text we have today.

For centuries we in the West have wondered whether intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe. If there are highly advanced, intelligent beings out there, what might they have to teach us? What have they learned that we have not? Along similar lines we can ask: is there intelligent life on our planet outside of our Euro-American civilization? Of course that sounds like a dumb question, but it's still worth asking, since there still persists an attitude in our society that we know more about everything than any previous generation and more than any other, less developed society today. It takes quite an ethnocentric leap of faith to swallow that, but many people seem to manage it. Indian civilization a thousand years ago, during the time of Atisha, had evolved with very little influence from European civilization; and Tibetan civilization, tracing back more than two millennia, was hardly influenced by the West until the mid-twentieth century. Ironically, Tibetans' first major encounter with Western thought occurred due to the invasion of their homeland by the Chinese Communists in 1949, who forced upon them the economic doctrine of Marxism and scientific materialism.

...lo means attitude, mind, intelligence, and perspective; and jong means to train, purify, remedy, and clear away. So the word lojong could literally be translated as attitudinal training.

Have Indian and Tibetan civilizations made any great discoveries of their own that we have not, and might they have anything to teach us? I will be tackling these questions throughout this book, drawing on a thousand-year-old set of aphorisms that embody much of the wisdom of ancient India and Tibet. If these aphorisms strike a chord of wisdom for us living today, whose lives span the end of the second millennium and the beginning of the third, that wisdom will be something that is not uniquely Eastern or Western, and not ancient or modern. It will be a type of wisdom that cuts across such cultural divides and eras, something universal that speaks deeply to and from the hearts and minds of humanity.

Over the past millennium, Tibetan Buddhism has maintained its vitality from generation to generation by teachers passing on oral commentaries to traditional root texts such as the Seven-Point Mind-Training. Root texts preserve the depth and wisdom of the teachings, and the oral commentaries link these texts with the experiences and views of practitioners of each generation. In the explanation of the text I offer here, I draw upon the earliest Tibetan commentary I have been able to find, composed by Sechil Buwa, who was a direct disciple of Chekawa Yeshe Dorje (1101-1175), who first wrote down this mind-training. Chekawa Yeshe Dorje had received the transmission of this teaching from Sharawa Yönten Drak, and the lineage before him goes back to Langri Thangpa, Potowa, Dromtonpa, and Atisha. I also draw on a very recent commentary entitled Enlightened Courage: An Explanation of Atisha's Seven Point Mind Training by the late Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of the greatest Tibetan meditation masters of the twentieth century.

The teacher from whom I received the oral commentary on this training was a learned, humble, and compassionate Tibetan named Kungo Barshi. I was living in Dharamsala, India, at the time, in 1973, and there were many erudite lamas from whom I could have sought this instruction. But I was particularly drawn to Kungo Barshi for various reasons. At that time, he was the chief instructor in Tibetan medicine at the Tibetan Astro-Medical Institute, and he was renowned for his mastery of many of the fields of traditional Tibetan knowledge. But he was not only an outstanding scholar. As a member of the nobility in Tibet, he had owned several estates and devoted himself to the life of a gentleman scholar, while his wife largely took over the practical affairs of running their estates. But when the Chinese Communists invaded Tibet and especially targeted the aristocracy for imprisonment and torture, he, his wife, and one of his sons fled to India. Others of his children remained behind, only to be killed by the Chinese, and the son who fled with him into exile also met a tragic end. Adversity mounted upon adversity in Kungo Barshi's life, and yet when he was passing on this teaching to me, he told me, Personally, I have found the Chinese invasion of Tibet to be a blessing. In Tibet before this cataclysm, I took much for granted, and my spiritual practice was casual. Now that I have been forced into exile and have lost so much, my dedication to practice has grown enormously, and I have found greater contentment than ever before. Rarely have I met anyone whose presence exuded such serenity, quiet good cheer, and wisdom as he did. He was for me a living embodiment of the efficacy of this mind-training, and his inspiration has been with me ever since.

As I pass on my own commentary to this text, I address many practical and theoretical issues that uniquely face us in the modern world. This book is based on a series of public lectures I gave in Santa Barbara, California, during the years 1997-1998. I have tried at all times to be faithful to the original teachings I received, while making them thoroughly contemporary to people living in a world so different from that of traditional Tibet. If even a fraction of the wisdom and inspiration of Atisha, Sechil Buwa, Kungo Barshi, and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche is conveyed to the readers of this book, our efforts will have born good fruit.

Related Books:

The Seventh Dalai Lama on Gems of Wisdom

| The following article is from the Autumn, 1999 issue of the Snow Lion Newsletter and is for historical reference only. You can see this in context of the original newsletter here. |

Gems of Wisdom

from the Seventh Dalai Lama

Translated by Glenn H. Mullin

The Seventh Dalai Lama (1708-1757) stands as one of the most beloved Buddhist masters in Tibet's long and illustrious history.

One of his most popular works is Gems of Wisdom, a collection of spontaneous short verses that employ earthy metaphors to illustrate key points in the enlightenment tradition. His language is simple and direct, capturing the profound spirituality of his vision while avoiding any form of religiosity. Here we find all the teachings of the Buddha brought into the context of their implications for individual transformation, or training of the mind.

Buddhism regards the human world as a training ground for the enlightenment process.

This volume presents a translation of this important text and also provides a brief commentary which elucidates the quintessential meanings embedded in the Seventh Dalai Lama's verses.

Glenn H. Mullin studied Tantric Buddhism in the Himalayas for twelve years, and has over a dozen books in print. In addition to his writings, he has co-produced numerous recordings of Tibetan sacred music, and also worked on three feature-length documentary films and four television productions related to Tibetan Buddhism.

Excerpt from Gems of Wisdom:

What is the body odor

easy to acquire but hard to lose?

Habits picked up from people

whose lives are far from spiritual ways.

The present era is called kaliyuga, or the dark age, for in it we are confronted by five harsh conditions: life-force is weak; delusions and afflicted emotions predominate everywhere; the times are violent; the living beings presently incarnate are mostly of low character; and false ideas and attitudes are mistaken for truth.

Buddhism regards the human world as a training ground for the enlightenment process. Living beings take rebirth here in order to learn and evolve. The conditions of the human environment change with the millennia in order to suit the needs of the trainees. Those riding the winds of positive karma are born as humans in a particular time and place in order to meet with those conditions most appropriate to their needs.

The present era is called kaliyuga, or the dark age, for in it we are confronted by five harsh conditions: life-force is weak; delusions and afflicted emotions predominate everywhere; the times are violent; the living beings presently incarnate are mostly of low character; and false ideas and attitudes are mistaken for truth. As a result, human civilization is filled with social structures, philosophical attitudes and behavioral norms that are in direct contradiction to and obstructive of spiritual growth.

Human civilization is filled with social structures, philosophical attitudes and behavioral norms that are in direct contradiction to and obstructive of spiritual growth.

On the positive side, the smallest point of light is clearly visible simply because everything is so dark, just as a candle flame in the daylight is almost invisible but at night is clearly seen from a great distance. Similarly, those born in the kaliyuga who enter into the path of spiritual knowledge quickly achieve their goals, for the steps on the path are easily distinguished.

The biggest obstacle to enlightenment in the kaliyuga is the temptation to follow the norms of society, for society is mostly on the wrong track. Therefore when the eleventh-century Kadampa master Lama Drom Tonpa was once asked how best to follow the path of spiritual knowledge he replied,

The masses have their heads on backwards. If you want to get things right, first look at how they think and behave, and consider going the opposite way.

the smallest point of light is clearly visible simply because everything is so dark...

Who suffer most deeply of all the beings in the world? Those with no self-discipline who are overpowered by delusion.

Generally speaking a person is always in one of two types of mind states: shen-wang, or other-powered and rang-wang, or self-powered. The former refers to the times when we do not keep the mind in positive spheres, and consequently are driven by distorted emotional or cognitive states; the latter refers to when we keep the mind focused through the application of spiritual methods.

It could also be said that there are two types of living beings: those who are directed mainly by negative mind states, and thus are mainly other-powered, and those who are directed mainly by spiritual forces, and thus are mainly self-powered. The second of the two have eliminated the coarse delusions and afflicted emotions, and have aroused the innate seeds of wisdom. Thus they hold the reins of their destiny in their own hands.

those who are directed mainly by spiritual forces, and thus are mainly self-powered (and) hold the reins of their destiny in their own hands.

Distorted mind states and afflicted emotions are the principal inner agents giving rise to external courses of action that create unhappiness for self and others. Due to anger, attachment, jealousy, prejudiced attitudes and so forth we misjudge the dynamics of the moment and mistake the flow of energies that constitute the transformations of body, speech and mind.

The remedy is the taming of the negative mind and the arousal of wisdom. However, these goals are not easily or quickly accomplished. Therefore those who have taken up the enlightenment path rely upon self-discipline. We cannot always have the wisdom to be free of anger, but through the will-power of self-discipline we can refrain from acts based on anger. Similarly, we may not yet have the wisdom that is free from prejudices, but we can discipline ourselves to mind our own business.

The remedy is the taming of the negative mind and the arousal of wisdom.

Undeveloped beings are almost always in a state of shen-wang. The more developed we become, the less time we spend in shen-wang states, and the more time in rang-wang, until eventually we achieve the transcendental wisdom that keeps us eternally in rang-wang.

Excerpt from Gems of Wisdom:

What is like a smelly fart

that, although invisible, is obvious?

One's own faults, that are precisely

as obvious as the effort made to hide them.

Ordinary people try to hide their faults and show what they think of as their good qualities. However, the more we try to hide a fault the more pronounced it becomes. The only remedy is the transcendence of the fault. As long as it still holds sway over us it is definite that it will continue to manifest.

The only remedy is the transcendence of the fault. As long as it still holds sway over us it is definite that it will continue to manifest.

The first step in overcoming our faults is the arousal of the determination to face and acknowledge them when they appear. Ordinary beings don't do this, and instead try to hide them from both self and others.

Of course, not everything that causes us embarrassment is a fault to be transcended. Ordinary social conditioning sometimes makes us ashamed of things of which we should be proud, and proud of things of which we should be ashamed. For this reason it is important to examine one's situation closely and not just take one's spiritual tradition for granted. But when it looks like a fault, smells like a fault and feels like a fault, most probably it is a quality to leave behind.

The early Kadampa lamas likened the Dharma to a mirror, and said that the practitioner should look at his or her face in this mirror and then clean it up in accordance with what is seen.

Excerpt from Gems of Wisdom:

What is an auspicious omen in country and city dweller alike?

Love, that seeks harmony amongst people,

and that wishes only happiness for others.

The term that the Seventh Dalai Lama uses here for harmony is puntsun yitu ongwa, which literally means seeing one another with affection. The yitu ongwa segment of the expression literally means delighting the mind, and is likened to the way a mother reacts to seeing her only child. The mere sight of the child brings pleasure and joy to the mind of the mother.

The presence of love in the mind immediately pacifies whatever negative energy is present in one's environment.

The quality of mind that always delights in the company of others, and that only wishes them well, is an auspicious omen in a person. Just as an auspicious omen seen in cloud formations, dreams or the like is a prophecy of good things to come, the quality of mind that always looks on others with affection and sympathy is an indication that the possessor of that mind is destined for happiness. When one has established the mind that always looks on others with love, one's experience of the world becomes more loving, peaceful and fulfilling.

The Buddha said,

The presence of love in the mind immediately pacifies whatever negative energy is present in one's environment. The force of the delusions is weakened, and the iron grip of negative karma is loosened.

Excerpt from Gems of Wisdom:

What is the one root of all

goodness in samsara and nirvana?

The clear light of one's own mind,

which by nature is free from every stain.

The basis of all conscious life is the mind, with its twofold quality of radiance and knowing. On its most subtle level, the mind is pure luminosity, or primordial clear light. Maitreya likened this aspect of the mind to the sky; the clouds of distortion and the delusions move through the sky and sometimes even obstruct the light of the sun, but they cannot actually harm or stain the sky. When conditions change, the clouds disappear and the pure sky shines through in all its glory.

Even the most seemingly evil person has the primordial clear light mind at the heart of his or her existence.

The essential nature of mind is equally pristine in all living beings, from earthworms to Buddhas. However, those on basic levels of consciousness fall prey to the distortions and delusions because of misapprehending the nature of the self. Moved by these factors they engage in negative behavior and bring suffering to self and others. Even the most seemingly evil person has the primordial clear light mind at the heart of his or her existence. Eventually the clouds of distortion and delusion will be cleared away as the being grows in wisdom, and the evil behavior that emanates from these negative mindsets will naturally evaporate. That being will realize the essential nature of his or her own mind, and achieve spiritual liberation and enlightenment.

The Buddha said,

The world is led by the mind. All good and evil deeds are created by it. It revolves like a fire wheel, moves like waves, burns like a forest fire, and widens like a great river.

As His Holiness the present Dalai Lama once put it,

The clear light mind, which lies dormant in living beings, is the great hope of mankind.

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is considered the foremost Buddhist leader of our time. The exiled spiritual head of the Tibetan people, he is a Nobel Peace Laureate, a Congressional Gold Medal recipient, and a remarkable teacher and scholar who has authored over one hundred books.

Related Books

Atisha's Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

$19.95 - Paperback

By: Atisha & Geshe Sonam Rinchen & Ruth Sonam

$21.95 - Paperback

By: H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Padmakara Translation Group